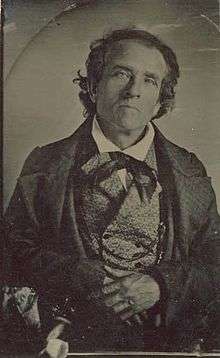

Theodore Dwight Weld

Theodore Dwight Weld (November 23, 1803 in Hampton, Connecticut – February 3, 1895 in Hyde Park, Massachusetts)[1] was one of the architects of the American abolitionist movement during its formative years from 1830 through 1844, playing a role as writer, editor, speaker, and organizer. He is best known for his co-authorship of the authoritative compendium American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, published in 1839. Harriet Beecher Stowe partly based Uncle Tom’s Cabin on Weld's text, and it is regarded as second only to that work in its influence on the antislavery movement. Weld remained dedicated to the abolitionist movement until slavery was ended by the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1865.[2]

Theodore Dwight Weld | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 23, 1803 |

| Died | February 3, 1895 (aged 91) Hyde Park, Massachusetts |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Hamilton College |

| Occupation | Abolitionist, writer, teacher |

| Employer | Society for Promoting Manual Labor in Literary Institutions (Lewis and Arthur Tappan), American Anti-Slavery Society |

| Known for | One of Charles Grandison Finney's "Holy Band"; leader of Lane Rebels |

Notable work | American Slavery as It Is |

| Spouse(s) | Angelina Grimké |

According to Lyman Beecher, father of Harriet Beecher Stowe, Weld was "as eloquent as an angel, and as powerful as thunder".[3]:323

Early life

Born in Hampton, Connecticut, the son and grandson of Congregational ministers, at age 14 Weld took over his father's 100 acres (40 ha) farm near Hartford, Connecticut, to earn money to study at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, attending from 1820 to 1822, when failing eyesight caused him to leave. After a doctor urged him to travel, he started an itinerant lecture series on mnemonics, traveling for three years throughout the United States, including the South, where he saw slavery first-hand. In 1825 Weld moved with his family to Pompey, in upstate New York.

College education

Weld then studied at Hamilton College in Clinton, Oneida County, New York. The famous evangelist Charles Finney was based in Oneida County, and while a student Weld must have attended some of Finney's many revivals, for he became Finney's disciple. In Utica, intellectual capital of western New York, center of abolitionism, and county seat of Oneida County, he met and became a good friend of Charles Stuart, an early abolitionist, who at that time (1822–1829) was head of the Utica Academy. They spent several years as members of Finney's "holy band" before he decided to become a preacher and in 1827 entered the Oneida Institute of Science and Industry in Whitesboro, New York, after first staying at the farmhouse of founder George Washington Gale in Western, New York, working in exchange for instruction. While at the Oneida Institute, he would spend two weeks at a time traveling about lecturing on the virtues of manual labor, temperance, and moral reform. "Weld...had both the stamina and charisma to hold listeners spellbound for three hours."[4]:29 As a result, by 1831 he had become a "well known citizen" of Oneida County, according to the Utica Elucidator.[5]

Weld was described thus by James Fairchild, who knew Weld from when they were students together at Oberlin (of which Fairchild would later be President):

Among these students was Theodore D. Weld, a young man of surpassing eloquence and logical powers, and of a personal influence even more fascinating than his eloquence. I state the impression which I had of him as a boy, and it may seem extravagant, but I have seen crowds of bearded men held spell-bound by his power for hours together, and for twenty evenings in succession.[6]:321

In an editorial comment in The Liberator, presumably by its editor Garrison, "Weld is destined lo be one of the great men not of America merely, but of the world. His mind is full of strength, proportion, beauty, and majesty.... [In his writing] "there is indubitable evidence of in lellectual grandeur and moral power."[7]

In his reminiscences of that period Dr. Beecher observed:

Weld was a genius. ...In the estimation of the class, he was president. He took the lead of the whole institution. The young men had, many of them, been under his care, and they thought he was a god. We never quarreled, however.[6]:321

In a completely different forum, William Garrison said that in a convention of antislavery "agents", who travelled from town to town giving abolitionist lectures and setting up new local anti-slavery societies, "Weld was the central luminary around which they all revolved".[8]:23

His future wife Angelina Grimké said in 1836, when she first laid eyes on him and heard him speak for two hours on "What is slavery?", that "I never heard so grand & beautiful an exposition of the dignity & nobility of man in my life".[8]:83.

Manual labor and education agent

His reputation as a speaker had reached New York, and in 1831, at the age of 28, Weld was called there by the philanthropists Lewis and Arthur Tappan. He declined their offer of a ministerial position, saying he felt himself unprepared. Since he was "a living, breathing, and eloquently-speaking exhibit of the results of manual-labor-with-study,"[9]:42, the brothers then created, so as to employ Weld, the Society for Promoting Manual Labor in Literary Institutions [schools], which promptly hired him as its "general agent" and sent him on a factfinding and speaking tour.[10]:25 (The Society never carried out any activities except hiring Weld, hosting some of his lectures, and publishing his report.)

Weld carried out this commission during the calendar year 1832; his report on his activities is dated January 10, 1833.[11]:100 In it he states that "In prosecuting the business of my agency, I have traveled during the year four thousand five hundred and seventy-five miles [7,364 km]; in public conveyances [boat and stagecoach], 2,630 [4,230 km]; on horseback, 1,800 [2,900 km]; on foot, 145 [233 km]. I have made two hundred and thirty-six public addresses."[11]:10 He was nearly killed when a high river swept away the coach he was in.[11]:vi[5]

Weld had also been commissioned to find a site for a great national manual labor institution where training for the western ministry could be provided for poor but earnest young men who had dedicated their lives to the home missionary cause in the "vast valley of the Mississippi." Such an institution would undoubtedly attract many of Weld's associates who had been disappointed in the failure to establish theological instruction at the Oneida Institute. Cincinnati was the logical location. Cincinnati was the focal center of population and commerce in the Ohio valley.[9]:43

During his year as a manual labor agent, Weld scouted land, found the location for, and recruited the faculty for the Lane Theological Seminary, in Cincinnati. He enrolled there as a student in 1833,[12] although he was informally the head, to the point of telling the trustees whom to hire. He had this power because on his recommendation the Tappans' subventions would continue, or go elsewhere (as they soon did).

Weld becomes an abolitionist

Some of his travel was in slave states. What he saw there, together with what he read in Garrison's newspaper The Liberator (1831) and book Thoughts on African Colonization (1832), turned him into a committed abolitionist. He first worked, in 1833, at convincing the other students at Lane that immediatism — ending slavery completely and immediately — was the only solution, and what God wanted. Successful at this, he next, with the Tappans' connivance, sought to bring immediatism to a larger audience. He announced that the public was invited to a series of public debates, over 18 evenings in February, 1834, on abolition versus colonization. In fact the debates were not debates at all, as no one spoke in favor of colonization. They were instead presentations of the horrors of American slavery, together with an exposé of the inadequacy of the American Colonization Society's project of helping free blacks migrate to Africa and its intent to preserve, rather than eliminate slavery. At the end the audience's views were highly supportive of immediate abolition.

At this point the debates were local events. However, during the Seminary's summer vacation of 1834, some of the students started teaching classes for and in other ways working to help the 1500 free African Americans of Cincinnati, with whom the students mixed freely. Given the pro-slavery sentiment in Cincinnati, many found this behavior unacceptable. After rumored threats of violence against the Seminary, the trustees passed rules abolishing the seminary's colonization and abolition societies and forbidding any further discussion of slavery, even at mealtimes. Weld was threatened with expulsion. A professor was fired. What happened was the mass resignation of almost all of Lane's student body, along with a sympathetic trustee, Asa Mahan. Later known as the Lane Rebels, they enrolled at the new Oberlin Collegiate Institute, insisting as conditions of their enrollment that they be free to discuss any topic (academic freedom), that Oberlin admit Blacks on the same basis as whites, and that the trustees not be able to fire faculty for any or no reason. The fired professor was hired by Oberlin, and Mahan became its first president.

Weld declined an appointment at Oberlin as professor of Theology, directing Shipperd to Charles Finney.[13]:3 Instead he took a position as agent of the American Anti-Slavery Society for Ohio. "He has, with characteristic disinterestedness, accepted this agency at one half the salary he was offered by another institution."[14]

Anti-slavery activity

Starting in 1834, Weld was an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society, recruiting and training people to work for the cause, making converts of James G. Birney, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Henry Ward Beecher. Weld became one of the leaders of the antislavery movement, working with the Tappan brothers, New York philanthropists James G. Birney and Gamaliel Bailey, and the Grimké sisters.

In 1836, Weld discontinued lecturing when he lost his voice, and was appointed editor of its books and pamphlets by the American Anti-Slavery Society.[12] In 1836–1840 Weld worked as the editor of The Emancipator.

In 1838, Weld married Angelina Grimké, a strong abolitionist and women's rights advocate; at the marriage there were two ministers, one white and one black. He renounced any power or legal authority over his wife, other than that produced by love. Two former slaves of the Grimkés' father were among the guests.[8]:317–318

He then retired to a farm in Belleville, New Jersey, where he, his wife, and her sister co-wrote the very influential 1839 book American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses. Angelina's unmarried older sister Sarah resided with them for many years.

In June 1840 the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London denied seats to Lucretia Mott and other women, mobilizing them to fight for women's rights, causing the U.S. abolitionist movement to split between nonviolent (but wanting it now, not gradually) "moral suasion" William Lloyd Garrison and his American Anti-Slavery Society, which linked abolition with women's rights, and Weld, the Tappan brothers and other "pragmatic" (gradualist) abolitionists, who formed the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (AFASS) and entered politics through the anti-slavery Liberty Party (ancestor of the Free-Soil Party and Republican Party), founded by James Birney, their U.S. presidential candidate in 1840 and 1844, who also founded the National Anti-Slavery Society.

In 1841–1843, Weld relocated to Washington, D.C., to direct the national campaign for sending antislavery petitions to Congress. He assisted John Quincy Adams when Congress tried him for reading petitions in violation of the gag rule, which stated that slavery could not be discussed in Congress.

Having demonstrated the value of an antislavery lobby in Washington, Weld returned to private life, where he and his wife spent the remainder of their lives directing schools and teaching in New Jersey and Massachusetts.

According to the Columbia Encyclopedia:

Many historians regard Weld as the most important figure in the abolitionist movement, surpassing even Garrison, but his passion for anonymity long made him an unknown figure in American history.[2]

In 1854, Weld established a school of the Raritan Bay Union at Eagleswood in Perth Amboy, New Jersey. The school accepted students of all races and sexes. In 1864 he moved to Hyde Park, Massachusetts, where he helped open another school, this one in Lexington, Massachusetts, dedicated to the same principles. Here, Weld had "charge of Conversation, Composition, and English Literature."[15]

Family

Weld was the son of Ludovicus Weld and Elizabeth Clark Weld. His brother Ezra Greenleaf Weld, a famous daguerreotype photographer, was also involved with the abolitionist movement.

A member of the Weld Family of New England, Weld shares a common ancestry with William Weld, Tuesday Weld, and others. This branch of the family never achieved the wealth of their Boston-based kin.[16][17]

Writings

- Weld, Theodore D. (1833). First annual report of the Society for Promoting Manual Labor in Literary Institutions, including the report of their general agent, Theodore D. Weld. January 28, 1833. New York: S. W. Benedict & Co.

- Weld, Theodore D. (June 14, 1834). "Discussion at Lane Seminary [letter to James Hall]". The Liberator. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- Weld, Theodore D. (1838). The Power of Congress over the District of Columbia. New York.

- Weld, Theodore D. (1837). The Bible Against Slavery. An inquiry into the Patriarchal and Mosaic systems on the subject of Human Rights (3rd, revised ed.). New York: American Anti-slavery Society. Weld received a published reply.[18]

- American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses (with the Grimké sisters; 1839)

- Weld, Theodore D. (1840). Persons held to service, fugitive slaves, &c. Boston: New England Anti-Slavery Tract Association.

- [Weld, Theodore D.] (1841). Slavery and the internal slave trade in the United States of North America; being replies to questions transmitted by the committee of the British and Foreign Anti-slavery Society, for the abolition of slavery and the slave trade throughout the world. Presented to the General Anti-slavery Convention, held in London, June 1840. London: British and Foreign Anti-slavery Society.

- Weld, Theodore D. (1850). "Slavery a System of Inherent Cruelty (excerpt from American Slavery As It Is)". Narrative of Sojourner Truth : a northern slave, emancipated from bodily servitude by the state of New York, in 1828 : with a portrait. Boston. pp. 127–140.

Legacy

- Another Lane Rebel, Huntington Lyman, named his son Theodore Weld Lyman (born 1840) for Weld.[19]

See also

References

Notes

- "Theodore Dwight Weld | Biography & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- Columbia 2003 Encyclopedia Article Archived 2009-02-25 at the Wayback Machine Columbia 2003 Encyclopedia Article

- Allen, William G. (March 1988). Calloway-Thomas, Carolyn (ed.). "Orators and Oratory". Journal of Black Studies. 18 (3): 313–336. JSTOR 2784510.

- Ellis, David Maldwyn (1990). "Conflicts Among Calvinists: Oneida Revivalists in the 1820s". New York History. 71 (1). pp. 24–44. JSTOR 23178274.

- "An Extraordinary Peril". Phenix Gazette (Alexandria, D.C.). March 23, 1832. p. 2.

- Beecher, Lyman (1866). Autobiography, Correspondence, Etc., of Lyman Beecher, D.D. 2. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- [Garrison, Wm. Lloyd] (June 14, 1834). "Letter from Theodore D. Weld". The Liberator. p. 3 – via newspapers.com.

- Ceplair, Larry (1989). The Public Years of Sarah and Angelina Grimké. Selected Writings 1835–1839. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 023106800X.

- Fletcher, Robert Samuel (1943). A history of Oberlin College from its foundation through the civil war. Oberlin College. OCLC 189886.

- Thomas, Benjamin Platt (1950). Theodore Weld, crusader for freedom. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. OCLC 6655058.

- Weld, Theodore D. (1833). First annual report of the Society for Promoting Manual Labor in Literary Institutions, including the report of their general agent, Theodore D. Weld. January 28, 1833. New York: S. W. Benedict & Co.

-

- Warfield, Benjamin Breckinridge (January 1921). Oberlin Perfectionism. Princeton Theological Review. 19.

- "Lane Seminary—Again". The Liberator. November 1, 1834. p. 2.

- The Massachusetts Teacher: A Journal of School and Home Education. September, 1864; Vol. IX No. 9: p. 353.

- "Harvard Magazine, "The Welds of Harvard Yard" by associate editor Craig Tom. Lambert". Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- Contrast 's views on slavery with those of distant relative Gen. Stephen Minot Weld Jr.

- Wisner, William C. The Biblical argument on Slavery. Being principally a review of T. D. Weld's Bible against Slavery. Firs published in the Quarterly Christian Spectator, September 1833. New-York: Leavitt, Trow & Co.

- "Huntington Lyman". Oberlin College. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

Further reading

- Letters of Theodore Dwight Weld, Angelina Grimké and Sarah Grimké, 1822-1844: Vols. 1 & 2. ISBN 0-8446-1055-0.

- Robert H. Abzug, Passionate Liberator: Theodore Dwight Weld & the Dilemma of Reform. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-19-503061-3.

- Gilbert Hobbs Barnes. The Anti-Slavery Impulse, 1830-1844. With an Introduction by William G. McLoughlin. New York: Harcourt, 1964.

- Nelson, Robert K. (Spring 2004). "'The forgetfulness of sex': Devotion and Desire in the Courtship Letters of Angelina Grimké and Theodore Dwight Weld". Journal of Social History. 37: 663–679.

External links

- Columbia 2003 Encyclopedia Article

- Theodore Weld: Crusader for Freedom (without footnotes)