The Titfield Thunderbolt

The Titfield Thunderbolt is a 1953 British comedy film directed by Charles Crichton and starring Stanley Holloway, Naunton Wayne, George Relph and John Gregson.[2] The screenplay concerns a group of villagers trying to keep their branch line operating after British Railways decided to close it. The film was written by T. E. B. Clarke [3] and was inspired by the restoration of the narrow gauge Talyllyn Railway in Wales, the world's first heritage railway run by volunteers. The name "Titfield" is an amalgamation of the villages of Limpsfield and Titsey in Surrey, near Clarke's home at Oxted.[4]

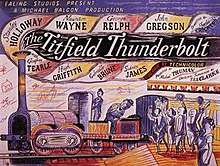

| The Titfield Thunderbolt | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Charles Crichton |

| Produced by | Michael Truman |

| Written by | T. E. B. Clarke |

| Starring | Stanley Holloway George Relph Naunton Wayne John Gregson Hugh Griffith Gabrielle Brune Sid James |

| Music by | Georges Auric |

| Cinematography | Douglas Slocombe |

| Edited by | Seth Holt |

| Distributed by | General Film Distributors (UK) Universal-International (US) |

Release date | 5 March 1953[1] |

Running time | 84 minutes |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

Michael Truman [5] was the producer. The film was produced by Ealing Studios and was the first of its comedies shot in Technicolor - one of the first such made in the UK.

There was considerable inspiration from the book Railway Adventure by established railway book author L. T. C. Rolt, published in 1952.[6] Rolt had acted as honorary manager for the volunteer enthusiasts running the Talyllyn Railway for the two years 1951–52. A number of scenes in the film, such as the emergency re-supply of water to the locomotive by buckets from an adjacent stream, or passengers being asked to assist in pushing the carriages, were taken from this book.

Plot

The residents of the village of Titfield are shocked to learn that their railway branch line to the town of Mallingford is to be closed. Sam Weech, the local vicar and a railway enthusiast, and Gordon Chesterford, the village squire, decide to take over the line by setting up a company through a Light Railway Order. Upon securing financial backing from Walter Valentine, a wealthy man with a fondness for daily drinking, the men learn that the Ministry of Transport will give them a month's trial period, in which they must pass an inspection at the end of this period to make the Order permanent. While Weech is helped by Chesterford and retired track layer Dan Taylor in running the train, volunteers from the village help to operate the station.

Bus operators Alec Pearce and Vernon Crump, who bitterly oppose the idea and wish to set up a bus line between Titfield and Mallingford, attempt to sabotage the men's plans. Aided by Harry Hawkins, a steam roller operator who hates the railway, Crump and Pearce attempt to block the line on its first run and sabotage the line's water tower, but are thwarted by Weech and the line's supportive passengers. After Chesterford refuses to accept a merger offer from them, Crump and Pearce hire Hawkins to help them derail the line's steam locomotive and only passenger car, the night before the line's inspection. Blakeworth, the village's solicitor, is mistakenly arrested for this, despite trying to stop the attempt, while the villagers become disheartened that their line will now close without any rolling stock and a working locomotive.

Valentine visits Taylor, who suggests that they borrow a locomotive from Mallingford's rail yards. Despite being both drunk, they manage to acquire one, but accidentally crash it after they're spotted taking it. Both men are promptly arrested by the police as a result. Meanwhile, Weech is inspired by a picture of the line's first locomotive, the Thunderbolt, which is now housed in the Mallingford's museum. Upon securing Blakeworth's release, he helps them to acquire the locomotive for the branch line. To complete their new train, the villagers use Taylor's home, an old railway carriage body, hastily strapped to a flat wagon. In the morning, Pearce and Crump drive to the village to prepare to take passengers, but are shocked to see the train waiting at the station. Distracted from his driving, Pearce crashes the bus into the police van transporting Valentine and Taylor, and when Crump lets slip that they have been involved in sabotaging the line they are promptly arrested.

With Taylor arrested, Weech takes help from Ollie Matthews, a fellow railway devotee and the Bishop of Welchester, in running the Thunderbolt for the inspection run. The train departs late because the police demand transport to Mallingford for them and the arrested men. Despite a mishap with the coupling, the villagers help the train complete its run to Mallingford. Upon arriving, Weech learns that the line passed every requirement for the Light Railway Order, but barely. In fact, had they been any faster, their application would have been rejected.

Cast

- Stanley Holloway as Walter Valentine

- George Relph as Vicar Sam Weech

- Naunton Wayne as George Blakeworth

- John Gregson as Squire Gordon Chesterford

- Godfrey Tearle as Ollie Matthews, the Bishop of Welchester

- Hugh Griffith as Dan Taylor

- Gabrielle Brune as Joan Hampton

- Sid James as Harry Hawkins

- Reginald Beckwith as Coggett

- Edie Martin as Emily

- Michael Trubshawe as Ruddock

- Jack MacGowran as Vernon Crump

- Ewan Roberts as Alec Pearce

- Herbert C. Walton as Seth

- John Rudling as Clegg

- Nancy O'Neil as Mrs Blakeworth

- Campbell Singer as Police Sergeant

- Frank Atkinson as Station Sergeant

- Wensley Pithey as Policeman

Driver Ted Burbidge, fireman Frank Green and guard Harold Alford were not actors: they were British Railways employees from the Westbury depot, provided to operate the train on location. Charles Crichton spoke with them on location and realised they "looked and sounded the part", so they were given speaking roles and duly credited.

Production

Shooting was largely carried out near Bath, Somerset, on the Camerton branch of the Bristol and North Somerset Railway, along the Cam Brook valley between Camerton and Limpley Stoke.[6] The branch had closed to all traffic on 15 February 1951, but was reopened for filming. Titfield railway station was in reality Monkton Combe railway station, whilst Titfield village was nearby Freshford, with other scenes being shot at the disused Dunkerton Colliery.[7] Mallingford railway station in the closing scene was Bristol Temple Meads railway station. The opening scene shows Midford Viaduct on the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway, where the branch passed under the viaduct. The scene featuring Sid James's character's traction engine, and the Squire's attempts to overtake it, was filmed in Carlingcott.

The scene where a replacement locomotive is 'stolen' was filmed in the Oxfordshire town of Woodstock. The 'locomotive' was a wooden mock-up mounted on a lorry chassis; the rubber tyres can (just) be spotted between the locomotive's driving wheels.[8] The earlier scene of No. 1401 crashing and getting wrecked as it heads down an embankment used realistic scale models.

The Thunderbolt itself was represented by an actual antique museum resident, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway locomotive Lion, built in 1838 and so at the time 114 years old.[8] Lion is one of the earliest British locomotives, built only nine years after Stephenson's Rocket and running under its own power in the film.[9] It was repainted in a colourful red and green livery to suit the Technicolor cameras. When filming the scene in which the Thunderbolt is "rear-ended" by the uncoupled train, the locomotive's tender sustained some actual damage, which remains visible beneath the buffer beam to this day. The scene where Thunderbolt is removed at night from its museum was filmed in the (now demolished) Imperial Institute building near the Royal Albert Hall in South Kensington, London. All these shots were made using a studio-built model.

Release

The film had its gala premiere at London's Leicester Square Theatre on 5 March 1953, as part of the British Film Academy's award ceremony, before going on general release from the 6th.[1]

Critical reception

The BFI's Monthly Film Bulletin for April 1953 found the script disconcertingly short on wit, and some of its invention seems forced.' [10]

The film has become compared unfavourably with other Ealing comedies. Ivan Butler in his Cinema in Britain called it 'A minor Ealing perhaps even a little tired towards the evening of their long comedy day but a very pleasant sunset for all that.' [11] George Perry in his history of the Ealing Studios, Forever Ealing, pointed out that like Whisky Galore and Passport to Pimlico the film 'adopted the theme of the small group pitted against and universally triumphing over the superior odds of a more powerful opponent.' But, quoting a location report by Hugh Samson of Picturegoer, he suggests there was a lack of sympathy for the subject: 'Odd point about this railway location: not a single railway enthusiast to be found in the whole crew. T.E.B.'Tibby' Clarke, writer of the script, loathes trains. Producer Michael Truman can't get out of them fast enough. And director Crichton - well, you wouldn't find him taking engine numbers at Paddington Station.' [12] Charles Barr in Ealing Studios felt that the film did not identify with audiences who for instance in Passport to Pimlico were yearning for the end of rationing; 'There is no grasp of a living community, or of the relevance of the train to people's daily needs.' [13]

References

- "The Titfield Thunderbolt". Art & Hue. 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953) - IMDb, retrieved 24 April 2020

- The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953) - IMDb, retrieved 24 April 2020

- Castens, Simon (February 2011). "The Titfield Thunderbolt and the Camerton Branch" (PDF). Address to Wells Railway Fraternity.

- The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953) - IMDb, retrieved 24 April 2020

- Roberts 2018, p. 58.

- Roberts 2018, p. 60.

- Roberts 2018, p. 61.

- Roberts 2018, p. 62.

- L, G (April 1953). "Titfield Thunderbolt, The". Monthly Film Bulletin. 231/20: 51.

- Butler, Ivan (1973). Cinema in Britain. A.S. Barnes. p. 201. ISBN 049801133X.

- Perry, George, 1935- (1981). Forever Ealing : a celebration of the great British film studio. London: Pavilion. p. 111. ISBN 0-907516-06-8. OCLC 8409427.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Barr, Charles. (1977). Ealing studios. London: Cameron & Tayleur. p. 163. ISBN 0-7153-7420-6. OCLC 3249510.

Sources

- Roberts, Steve (28 March 2018). "Thunderbolt enlightening". Rail magazine. No. 849. Peterborough: Bauer Media. ISSN 0953-4563.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Fosker, Oliver (1 November 2008). The Titfield Thunderbolt ~ Now & Then. Up Main Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9561041-0-6.

- Castens, Simon (22 July 2002). On the Trail of The Titfield Thunderbolt. Thunderbolt Books. ISBN 978-0-9538771-0-2.

- Huntley, John (1969). Railways in the Cinema. Ian Allan. pp. 76–79. ISBN 978-0-7110-0115-2.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (June 1996). Frome to Bristol including the Camerton Branch and the "Titfield Thunderbolt". Middleton Press. ISBN 978-1-873793-77-0.

External links

- The Titfield Thunderbolt on IMDb

- The Titfield Thunderbolt Filming Locations

- http://www.lionlocomotive.org.uk/ Lion, an interesting 'Old Locomotive', probably best known as taking a starring part in the film Titfield Thunderbolt