The String of Pearls

The String of Pearls: A Domestic Romance is the title of a fictional story first published as a penny dreadful serial from 1846–47. The main antagonist of the story is Sweeney Todd, "the Demon Barber of Fleet Street", who here makes his literary debut, and from whom one of the alternative titles of the story is derived. The other alternative title of the story is The Gift of the Sailor.

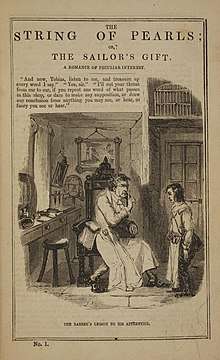

Page from The String of Pearls; or, The Sailor’s Gift, 1850 | |

| Author | Unknown but probably James Malcolm Rymer and/or Thomas Peckett Prest |

|---|---|

| Working title | The Barber of Fleet Street. A Domestic Romance |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Sweeney Todd |

| Genre | Fiction |

| Set in | London |

| Published | 1846–47 by Edward Lloyd 1850 as a book |

| Media type | Print (Penny dreadful) |

| Pages | 732 pp (Book) |

| OCLC | 830944639 |

| LC Class | PR5285.R99 |

| Text | The String of Pearls at Wikisource |

Todd is a barber who murders his customers and turns their bodies over to Mrs. Lovett, his partner in crime, who bakes their flesh into meat pies. His barber shop is situated in Fleet Street, London, next to St. Dunstan's church, and is connected to Lovett's pie shop in nearby Bell Yard by means of an underground passage. Todd dispatches his victims by pulling a lever while they are in his barber chair, which makes them fall backward down a revolving trapdoor and generally causes them to break their necks or skulls on the cellar floor below. If the victims are still alive, he goes to the basement and "polishes them off" by slitting their throats with his straight razor.

Synopsis

The story is set in London in the year 1785. The plot concerns the strange disappearance of a sailor named Lieutenant Thornhill, last seen entering Sweeney Todd's establishment on Fleet Street. Thornhill was bearing a gift of a string of pearls to a girl named Johanna Oakley on behalf of her missing lover, Mark Ingestrie, who is presumed lost at sea. One of Thornhill's seafaring friends, Colonel Jeffrey, is alerted to the disappearance of Thornhill by his faithful dog, Hector, and investigates his whereabouts. He is joined by Johanna, who wants to know what happened to Mark.

Johanna's suspicions of Sweeney Todd's involvement lead her to the desperate and dangerous expedient of dressing up as a boy and entering Todd's employment after his last assistant, a young boy named Tobias Ragg, has been incarcerated in a madhouse for accusing Todd of being a murderer. Soon, after Todd has dismembered his bodies, Mrs. Lovett creates her meat pies from the leftover flesh. While the bodies are burning in the oven, a ghastly and intolerable smell reeks from the pie shop chimney. Eventually, the full extent of Todd's activities is uncovered when the dismembered remains of hundreds of his victims are discovered in the crypt underneath St. Dunstan's church. Meanwhile, Mark, who has been imprisoned in the cellars beneath the pie shop and put to work as the cook, escapes via the lift used to bring the pies up from the cellar into the pie shop. Here he makes the following startling announcement to the customers of that establishment:

- "Ladies and gentlemen – I fear that what I am going to say will spoil your appetites; but the truth is beautiful at all times, and I have to state that Mrs. Lovett's pies are made of human flesh!"[1]

Mrs. Lovett is then poisoned by Sweeney Todd, who is subsequently apprehended and hanged. Johanna marries Mark and lives happily ever after.

Literary history

The String of Pearls: A Romance was published in eighteen weekly parts, in Edward Lloyd's The People's Periodical and Family Library, issues 7–24, 21 November 1846 to 20 March 1847. It is frequently attributed to Thomas Peckett Prest, but has been more recently been reassigned to James Malcolm Rymer;[2] other names have also been suggested. The story was then published in book form in 1850 as "The String of Pearls", subtitled "The Barber of Fleet Street. A Domestic Romance". This expanded version of the story was 732 pages long, and its conclusion differs greatly from that of the original serial publication: Todd escapes from prison after being sentenced to death but, after many further adventures, is finally shot dead while fleeing from the authorities. In later years there were many different literary, stage and eventually film adaptations which renamed, further expanded and often drastically altered the original story.[1]

A scholarly, annotated edition of The String of Pearls was published in 2007 by the Oxford University Press under the title of Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, edited by Robert Mack.

Themes

Penny dreadfuls were often written carelessly and contained themes of gore and violence. The String of Pearls is no different. Its style of writing makes it a perfect example of a penny dreadful, having a sensational, violent subject matter that plays off of the public's real fears. The success of the stories lies in the gut reaction people have towards it. Themes like murder and cannibalism equally scare and attract people and lead to the success of the stories. The story plays on our instinctual fear of cannibalism, the eating of one's own species. Being such a taboo, the theme of cannibalism contributes to the horror tone of the story. Unknowingly being served human to eat is a common fear in popular culture.

Industrialisation is a theme that contributes to the unfolding of the story as it was published in the 1840s in the midst of Great Britain's Industrial Revolution. Sweeny Todd owns a barber shop in the middle of one of the busiest industrial centres of the growing city of London. The rise of industrialism resulted in rising crime rates. This rise of crime was immensely influential when it came to the String of Pearls and other penny dreadful stories that revolved around the fearful ideas and themes of crime, fear, and gore.

Historical background

While there is no clear author of the 19th century String of Pearls in the original penny dreadful, there are many theories surrounding its influences. In the Victorian time, when this story was first written, a semi-common trade was what was called a barber-surgeon. Barber-surgeons cropped up around this time as trained medical practitioners, not through school but through apprenticeship and they were illiterate. The story goes that in front of a barber-surgeons workplace there would be a red and white pole (much like in front of Sweeney Todd's shop), symbolizing the blood and napkins used during the bloodletting. In 1745, surgery became an established and well regarded profession of its own and the two were officially separated by King George II.[3]

Speculated influences

Le Theatre des Antiquites de Paris

Le Theatre des Antiquites de Paris by Jacques du Breuil contains a section titled De la maison des Marmousets that talks of a "murderous pastry cook" who incorporates into his pie the meat of a man he murdered due to dietary benefits over eating other animals.[4]

Historical basis for Sweeney Todd

It has been speculated that, "Joseph Fouché, who served as Minister of Police in Paris from 1799 to 1815, had records in the archives of police that explored murders committed in the 1800s by a Parisian barber".[5] Fouche made mention that the barber was in league with "a neighbouring pastry cook, who made pies out of the victims and sold them for human consumption".[5] There is question about the authenticity of this account, "yet the tale was republished in 1824 under the headline A Terrific Story of the Rue de Le Harpe, Paris in The Tell Tale, a London magazine. Perhaps Thomas Prest, scouring publications for ideas, read about the Paris case and stored it away for later use."[5]

Sweeney Todd's story also appears in the Newgate Calendar, originally a bulletin of executions produced by the keeper of Newgate prison, the title of which was appropriated by chapbooks, popular pamphlets full of entertaining, often violent criminal activities.[6] Despite this mention there is no word of Todd's trial or execution in official records, and thus no real evidence that he ever existed.[6]

No public records prove any existence of a London barber by the name of Sweeney in the 18th century or of a barber shop located on Fleet Street. There were many word-of-mouth, true crime and horror stories travelling around at the time however, reported in "The Old Bailey" section of the London Times as well as other daily newspapers. News also commonly travelled by word of mouth as the majority of the population was still illiterate, and could become embellished in the retelling from person to person. Such news would still be taken as factual upon hearing because there was no way of proving otherwise at the time.[7]

Charles Dickens

In Charles Dickens' The Pickwick Papers (1836–37), Pickwick's cockney servant Sam Weller states that a pieman used cats "for beefsteak, veal and kidney, 'cording to the demand", and recommends that people should buy pies only "when you know the lady as made it, and is quite sure it ain't kitten".[8] Dickens expanded on the idea of using non-traditional sources for meat pie in Martin Chuzzlewit (1843–44). This was published two years before The String of Pearls (1846–47) and included a character by the name of Tom Pinch, who feels lucky that his own "evil genius did not lead him into the dens of any of those preparers of cannibalic pastry, who are represented in many country legends as doing a lively retail business in the metropolis" and worries that John Westlock will "begin to be afraid that I have strayed into one of those streets where the countrymen are murdered; and that I have been made into meat pies, or some such horrible thing".[9][10] Peter Haining suggested in a 1993 book that Dickens was inspired by knowledge of the "real" Sweeney Todd, but that he forbore to mention him lest some of his victims' relatives were still alive.[6]

References

- Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street edited by Robert L. Mack (2007). Oxford University Press: 280

- Smith, Helen R. (2002). New light on Sweeney Todd. London: Jarndyce. p. 28.

- "Science Museum. Brought to Life: Exploring the History of Medicine." Barber-surgeons. Web.

- Mack, Robert L. The Wonderful and Surprising History of Sweeney Todd: The Life and Times of an Urban Legend. London: Continuum, 2007. Print.

- "True Criminals". pbs.org. KQED, Inc. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Welsh, Louise (19 January 2008). "On A Knife Edge". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Suer, Kinsley. "PCS Blog - The Real Sweeney Todd? From Penny Dreadful to Broadway Musical." Portland Center Stage. N.p., 4 Oct. 2012. Web. 20 Nov. 2014. <http://www.pcs.org/blog/item/the-real-sweeney-todd-from-penny-dreadful-to-broadway-musical/>.

- Dickens, Charles. The Pickwick Papers. Oxford: Oxford Classics. pp. 278, 335

- Charles Dickens, Martin Chuzzlewit, ed. Margaret Cardwell (1982). Oxford, Clarendon Press: 495

- Sweeney Todd

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |