The Parallax View

The Parallax View is a 1974 American political thriller film produced and directed by Alan J. Pakula, and starring Warren Beatty, Hume Cronyn, William Daniels and Paula Prentiss. The screenplay by David Giler and Lorenzo Semple Jr. was based on the 1970 novel by Loren Singer. Robert Towne did an uncredited rewrite. The story concerns a reporter's investigation into a secretive organization, the Parallax Corporation, whose primary focus is political assassination.

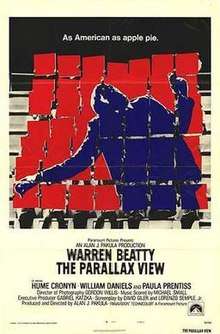

| The Parallax View | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alan J. Pakula |

| Produced by | Alan J. Pakula |

| Screenplay by | David Giler Lorenzo Semple Jr. Uncredited: Robert Towne |

| Based on | The Parallax View by Loren Singer |

| Starring | Warren Beatty Hume Cronyn William Daniels Paula Prentiss |

| Music by | Michael Small |

| Cinematography | Gordon Willis |

| Edited by | John W. Wheeler |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 102 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The Parallax View is the second installment of Pakula's Political Paranoia trilogy, along with Klute (1971) and All the President's Men (1976). In addition to being the only film in the trilogy not to be distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures, The Parallax View is also the only one of the three not to be nominated for an Academy Award.

Plot

TV newswoman Lee Carter witnesses the assassination of presidential candidate Charles Carroll atop Seattle's Space Needle. A waiter armed with a revolver is pursued and falls to his death while a second waiter, also armed, leaves the scene unnoticed. A congressional committee decides the killing was the work of the dead waiter but conspiracy theories subsequently arise. Three years later, Carter visits her former boyfriend, newspaper reporter Joe Frady, claiming others must have been behind the assassination as six of the witnesses to the killing have since died and she fears she will be next. Frady does not take her seriously. Carter is soon found dead in what is officially ruled as a massive drug overdose coupled with a DUI.

Guilty over disregarding Carter's pleas for her safety, Frady goes to the small town of Salmontail to probe the recent death of Judge Arthur Bridges, also a witness. An apparently spontaneous bar fight with the Salmontail sheriff's deputy draws the attention of the sheriff himself, L. D. Wicker, who offers to take Frady to the spot where Bridges drowned. When they arrive at the dam, however, Wicker pulls his gun on Frady while the floodgates are opening, plotting to have him drown the same way Bridges did. Frady whips Wicker with his fishing rod, and they tussle in the rapids. Frady manages to make it to the rocks of the river bank, while Wicker drowns. Frady commandeers Wicker's squad car, and at the sheriff's house he uncovers documents about the Parallax Corporation. The documents reveal the organization recruits political assassins.

While Frady collects the documents, the deputy arrives at the residence, letting himself in. Frady grabs the documents and attempts to escape in Wicker's squad car, with the deputy in pursuit. Frady smashes the squad car through the front of a grocery store, and escapes through the back, jumping into the back of a passing commercial vehicle.

Frady tries to convince his skeptical newspaper editor Bill Rintels he is onto a big story, connecting the dots of witnesses of assassinations who have died, but Rintels refuses to support his efforts. Undaunted, Frady seeks out a local psychology professor, Dr. Schwartzkopf, who assesses the Parallax Corporation's personality test taken from Wicker's desk, and deems it to be likely a profiling exam to identify psychopaths.

Austin Tucker, the paranoid aide to the assassinated Carroll, agrees to meet Frady on his boat, while anxiously revealing there have been two attempts on his life since Carroll's assassination. Shortly after Tucker shows photos to Frady of a suspicious waiter who may have been involved in Carroll's shooting, a bomb explodes onboard, killing Tucker and his assistant. Frady survives by diving overboard but is believed to be dead.

Later that night, Frady slips into the newspaper's offices, startling a sleeping Rintels, revealing he's alive despite reports that he died in the boat accident. Moreover, he informs Rintels of his belief he's uncovered an organization that recruits assassins, and wants the public to believe he is dead so he can apply to the Parallax Corporation under an assumed identity.

Days later, Jack Younger, a Parallax official, pays him a visit to let him know he is, based on his preliminary application, the kind of man Parallax is interested in. Younger is encouraged by Frady's aggressive act of throwing a pot that has burned his hand against the wall. Frady is accepted for training in the Parallax Corporation's division of Human Engineering in Los Angeles, where he is instructed to watch a slide show conflating positive images with negative actions.

While leaving the Parallax's offices, Frady recognizes one of the Parallax operatives from a photo Tucker showed him, as the second waiter from Carroll's assassination. He watches the assassin retrieve a case from a car, drive to an airport, and check it as stowed baggage on a passenger jet. Frady boards the plane and notices a senator aboard, but cannot find the assassin, who is actually watching the jet's takeoff from the airport's roof. Frady writes a warning, that there is a bomb on board, on a napkin and slips it onto the drink service cart. The warning is found and the jet returns to Los Angeles. Passengers are evacuated moments before the bomb explodes.

Returning to his apartment, Frady is confronted by Younger about not being the man whose identity he has been using. Frady 'confesses' he is actually yet another man who had gotten in trouble with the police, and Younger agrees to validate this new identity. Later, at the newspaper office, Rintels listens to a secretly recorded tape of the conversation between Frady and Younger, then places it in an envelope with other such tapes. Rintels is poisoned by the senator's killer and bomb-planter, now disguised as a sandwich delivery man, and the tapes disappear.

Frady goes to the Parallax offices to see Younger, and is told he is not there, but then sees him leaving the building. He follows the operative to the dress rehearsal for a political rally for Senator George Hammond and hides in the auditorium's catwalks to observe Parallax agents, who are posing as security personnel. Frady attempts to follow one of the men back to the auditorium, but finds he had been locked in the catwalk area. As Hammond drives a golf cart across the auditorium floor, an unseen sniper shoots him in the back, killing him, causing pandemonium below.

Frady realizes too late he has been set up as a scapegoat and attempts to flee across the catwalks, but is spotted by the police who are now in the auditorium below. As Frady runs to the reopened exit door from the catwalks, a shadowy agent steps through, killing Frady with a shotgun. Six months later, the same shadowy committee that investigated Carroll's death reports that Frady, acting alone, killed Hammond out of paranoia and misguided patriotism and express the hope that the verdict will end conspiracy theories about political assassinations.

Cast

- Warren Beatty as Joseph Frady

- Paula Prentiss as Lee Carter

- Hume Cronyn as Bill Rintels

- William Daniels as Austin Tucker

- Kenneth Mars as former FBI agent Will Turner

- Walter McGinn as Jack Younger

- Kelly Thordsen as Sheriff L. D. Wicker

- Jim Davis as Senator George Hammond

- Bill McKinney as Parallax assassin

- William Jordan as Tucker's aide

- Edward Winter as Senator Jameson

- Chuck Waters as Thomas Richard Linder

- Earl Hindman as Deputy Red

- William Joyce as Senator Charles Carroll

- Jo Ann Harris as Chrissy, Frady's girl

- Doria Cook-Nelson as Gale from Salmontail

- Ford Rainey as Commission spokesman #2

- Richard Bull as Parallax goon

- Anthony Zerbe as Prof. Nelson Schwartzkopf (uncredited)

Production

Most of the images used in the assassin training montage were of anonymous figures or patriotic backgrounds, featuring among others Richard Nixon, Adolf Hitler, Pope John XXIII, and Lee Harvey Oswald (in the picture taken moments after his shooting). The montage also uses a drawing by Jack Kirby of the Marvel Comics character Thor.

The distinctive anamorphic photography, with long lens, unconventional framing, and shallow focus was supervised by Gordon Willis.

The river scene was filmed at the Gorge Dam, on the Skagit River (Ross Lake National Recreation Area) in Washington state. The Space Needle in Seattle, Washington is featured extensively in the first assassination sequence.

The airport scene was filmed at Bob Hope Airport in Burbank, California.

Critical reception

At the time of its release, The Parallax View received mixed reactions from critics. Roger Ebert gave the film three out of four stars and wrote, "The Parallax View will no doubt remind some reviewers of Executive Action (1973), another movie released at about the same time that advanced a conspiracy theory of assassination. It's a better use of similar material, however, because it tries to entertain instead of staying behind to argue."[1] In his review for The New York Times, Vincent Canby wrote, "Neither Mr. Pakula nor his screenwriters, David Giler and Lorenzo Semple, Jr., display the wit that Alfred Hitchcock might have used to give the tale importance transcending immediate plausibility. The moviemakers have, instead, treated their central idea so soberly that they sabotage credulity."[2] Time magazine's Richard Schickel wrote, "We would probably be better off rethinking—or better yet, not thinking about—the whole dismal business, if only to put an end to ugly and dramatically unsatisfying products like The Parallax View."[3]

In 2006, Entertainment Weekly critic Chris Nashawaty wrote, "The Parallax View is a mother of a thriller... and Beatty, always an underrated actor thanks (or no thanks) to his off-screen rep as a Hollywood lothario, gives a hell of a performance in a career that's been full of them."[4]

The motion picture won the Critics Award at the Avoriaz Film Festival (France) and was nominated for the Edgar Allan Poe Award for Best Motion Picture. Gordon Willis won the Award for Best Cinematography from the National Society of Film Critics (USA).

The film's reception has been more positive in recent years. It currently holds a 90% "Fresh" score on Rotten Tomatoes based on 29 reviews.

See also

- List of American films of 1974

- Assassinations in fiction

- List of films featuring surveillance

- The Manchurian Candidate

- Arlington Road

- Permindex

References

- Ebert, Roger (June 14, 1974). "The Parallax View". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- Canby, Vincent (June 20, 1974). "The Parallax View". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- Schickel, Richard (July 8, 1974). "Paranoid Thriller". Time. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- Nashawaty, Chris (July 11, 2006). "View Master". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Parallax View |