The Blue Dahlia

The Blue Dahlia is a 1946 American crime film and film noir, directed by George Marshall based on an original screenplay by Raymond Chandler.[3][4] The film stars Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake.[5] It was Chandler's first original screenplay.

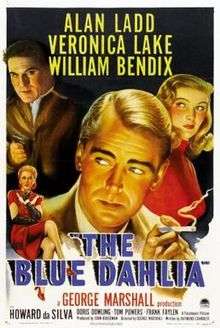

| The Blue Dahlia | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | George Marshall |

| Produced by | John Houseman |

| Screenplay by | Raymond Chandler |

| Starring | Alan Ladd Veronica Lake William Bendix |

| Cinematography | Lionel Lindon |

| Edited by | Arthur P. Schmidt |

Production company | Paramount Pictures |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 100 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $2,750,000 (US rentals)[1] 1,063,165 admissions (France)[2] |

Plot

Three discharged United States Navy aviators, Johnny Morrison, Buzz Wanchek and George Copeland, arrive in Hollywood, California. All three flew together in the same flight crew in the South Pacific. Buzz has shell shock and a metal plate in his head, above his ear.

While George and Buzz get an apartment together, Johnny surprises his wife, Helen, at her old apartment, which is patrolled by a house detective, "Dad" Newell. He discovers that she is having an affair with Eddie Harwood, the owner of the Blue Dahlia nightclub on the Sunset Strip. Helen, drunk, confesses to Johnny that their son Dickie, who Johnny believed died of diphtheria, actually died in a car crash that occurred because she was driving while drunk. Newell sees Johnny and Helen fight. Later, Johnny pulls a gun on Helen, but drops it and leaves.

Buzz goes out to find Johnny. He meets Helen and, unaware of her identity, goes to her bungalow for a drink.

Eddie breaks up with Helen, who then blackmails him into seeing her again.

Johnny is picked up in the rain by Joyce Harwood, who is separated from Eddie. Both do not reveal their name, and they spend the night in separate rooms in a Malibu inn. The next morning, they have breakfast, and he decides to give his marriage another chance. Then, the radio announces that Helen has been murdered and that Johnny is suspected.

The police interview Newell, Harwood, Buzz, and George.

After Johnny checks into a cheap hotel under an assumed name, Corelli, the hotel manager, finds Johnny's photo of himself with Dickie and tries to blackmail him. Johnny beats Corelli up and then discovers that on the back of the photo, Helen revealed that Eddie is really Bauer, a murderer who is wanted in New Jersey.

Corelli revives and sells information on Johnny's identity to a gangster named Leo, who kidnaps him.

Buzz and George visit Eddie at the Blue Dahlia. Joyce introduces herself. As Joyce picks at a blue dahlia flower, the nightclub's music sets off a painful ring in Buzz's head. Lapsing into a fit, he remembers the agonizing music that he heard at Helen's bungalow, as she played with a blue dahlia.

Johnny escapes Leo's henchmen as Eddie arrives and forces him to admit that 15 years earlier, he was involved in the shooting of a bank messenger.

Leo tries to shoot Johnny but hits Eddie instead. Johnny flees to the Blue Dahlia, where the police are trying to force a confused Buzz to admit that he killed Helen.

Johnny enters and suggests for Joyce to turn up the music. As his head pounds, Buzz remembers leaving Helen alive in her bungalow. Police Captain Henrickson then confronts Newell with the accusation that he tried to blackmail Helen about her affair and that when she refused to comply, he killed her. Newell then tries to escape from the office but is shot by Henrickson.

Later, outside the Blue Dahlia, Buzz and George decide to go for a drink, leaving Johnny and Joyce together.

Cast

- Alan Ladd as Johnny Morrison

- Veronica Lake as Joyce Harwood

- William Bendix as Buzz Wanchek

- Howard Da Silva as Eddie Harwood

- Doris Dowling as Helen Morrison

- Hugh Beaumont as George Copeland

- Tom Powers as Captain Hendrickson

- Howard Freeman as Corelli

- Don Costello as Leo

- Will Wright as "Dad" Newell

Production

Development

In 1945 Alan Ladd was one of Paramount's top stars. He had served for ten months in the army in 1943 before being honorably discharged due to illness; however, he was recently reclassified 1-A for the World War II military draft, and he might have had to go back into the Army. Paramount kept applying for deferments so he could make films but he was due for induction in May 1945.[6]

The studio wanted to make a movie starring him before that happened, but had nothing suitable. Producer John Houseman knew Raymond Chandler from having collaborated on Paramount's The Unseen, which Houseman produced and Chandler rewrote. Houseman says Chandler had started a novel but was "stuck" and was considering turning it into a screenplay for the movies instead. Houseman read the 120 pages Chandler had written and within 48 hours, it was sold to Paramount. Houseman would produce it under the supervision of Joseph Sistrom.[7]

It was the first original script for the screen that Chandler had ever written.[8][9] He wrote the first half of the script in under six weeks and sent it to Paramount. Delighted, the studio arranged for filming to start in three weeks time.[10]

Paramount announced the film in February 1945, with Ladd, Lake, Bendix, and Marshall all attached from the beginning.[11] Houseman said George Marshall had a reputation for rewriting extensively on the set and had to persuade him to stick to the script.[12] (Marshall said he was so impressed with the writing he never had any intention of rewriting.[13])

Houseman recalled that Ladd was unhappy with the casting of Doris Dowling as his wife because she was half a foot taller than he. The filmmakers placated him by having her sitting or lying down in their scenes together.[14]

Shooting

Shooting began in March 1945 without a completed screenplay. Houseman was not worried initially because of his confidence in Chandler. He says four weeks into filming the studio began to worry as they were running out of script. "We had shot sixty-two pages in four weeks; Chandler, during that time, had turned in only twenty-two—with another thirty to go."[15]

The problem was the ending. Originally, Chandler intended the killer to be Buzz having a blackout. However, the Navy did not want a serviceman to be portrayed as a murderer, and Paramount told Chandler that he had to come up with a new ending. Chandler responded at first with writer's block. Paramount offered Chandler a $5000 incentive to finish the script, which did not work, according to Houseman:

It was the front-office calculation, I suppose, that by dangling this fresh carrot before Chandler's nose they were executing a brilliant and cunning maneuver. They did not know their man. They succeeded, instead, in disturbing him in three distinct and separate ways: One, his faith in himself was destroyed. By never letting Ray share my apprehensions, I had convinced him of my confidence in his ability to finish the script on time. This sense of security was now hopelessly shattered. Two, he had been insulted. To Ray, the bonus was nothing but a bribe. To be offered a large additional sum of money for the completion of an assignment for which he had already contracted and which he had every intention of fulfilling was by his standards a degradation and a dishonor. Three, by going to him behind my back they had invited him to betray a friend and fellow Public School man. The way the interview had been conducted ('sneakily') filled Ray with humiliation and rage.[15]

Chandler wanted to quit, but Houseman convinced him to sleep on it. The next day, Chandler said he would be able to finish the film if he resumed drinking. Houseman said that the writer's requirements were "two Cadillac limousines, to stand day and night outside the house with drivers available," "six secretaries," and "a direct line open at all times to my office by day, to the studio switchboard at night and to my home at all times."[15] Houseman agreed and says Chandler then started drinking:

[Chandler] did not minimize the hazards [of drinking]," said Houseman in 1964, "He pointed out that his plan... would call for deep faith on my part and supreme courage on his, since he would in effect be completing the script at the risk of his life. (It wasn't the drinking that was dangerous, he explained, since he had a doctor who gave him such massive injections of glucose that he could last for weeks with no solid food at all. It was the sobering up that was parlous; the terrible strain of his return to normal living)."[15]

At the end of that time, Chandler presented the finished script.[16]

Chandler was unhappy with the forced ending, saying it made "a routine whodunnit out of a fairly original idea."[17] He also disliked the performance of Lake. "The only times she's good is when she keeps her mouth shut and looks mysterious," he told a friend. "The moment she tries to behave as if she had a brain she falls flat on her face. The scenes we had to cut out because she loused them up! And there are three godawful close shots of her looking perturbed that make me want to throw my lunch over the fence."[18]

Chandler received a lot of deference on the set, but Lake was not familiar with him so upon asking about him and being told, "He's the greatest mystery writer around," she made a point of listening intently to an analysis of his work by the film's publicity director to impress newspaper reporters with her knowledge of a writer she had never read.[19] Chandler developed an intense dislike for Lake and referred to her as "Moronica Lake".[20]

Lake later said about her role, "I'm not much of a motivating force, but the part is good."[21]

By May 1945 the government ruled that all men aged 30 or over would be released from the obligation to go back into the army. Ladd did not have to re-enlist after all.[22]

Reception

Box office

It was one of the most popular films at the British box office in 1946.[23]

Critical response

The staff at Variety magazine gave the film a positive review and wrote:

Playing a discharged naval flier returning home from the Pacific first to find his wife unfaithful, then to find her murdered and himself in hiding as the suspect, Alan Ladd does a bangup job. Performance has a warm appeal, while in his relentless track down of the real criminal, Ladd has a cold, steel-like quality that is potent. Fight scenes are stark and brutal, and tremendously effective.[24]

Critic Dennis Schwartz wrote:

A fresh smelling film noir directed with great skill by George Marshall from the screenplay of Raymond Chandler (the only one he ever wrote for the screen, his other films were adapted from his novels). It eschews moral judgment in favor of a hard-boiled tale that flaunts its flowery style as its way of swimming madly along in LA's postwar boom and decadence.[25]

Diabolique called it "a fantastic film noir, full of atmosphere, intrigue, crackling dialogue and sensational performances, which was recognized as a classic almost immediately and made a tonne of money." [26]

The film review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reports that 100% of its critics gave the film a positive review, with an average rating of 6.88/10, based on 8 reviews; and 71% of its audience gave the film a positive review with an average rating of 3.6 stars, based on 1,087 ratings.[27]

Accolades

Chandler was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay.[28]

Adaptations

The Blue Dahlia was dramatized as a half-hour radio play on the April 21, 1949 broadcast of The Screen Guild Theater, starring Lake and Ladd in their original film roles. The movie was also adapted into a stage play in 1989.[29]

Houseman's narrative of the film's creation was dramatized for BBC Radio by Ray Connolly in 2009.[30]

References

- "60 Top Grossers of 1946", Variety 8 January 1947 p8

- French box office of 1948 at Box Office Story

- Variety film review; January 30, 1946, page 12.

- Harrison's Reports film review; February 2, 1946, page 19.

- The Blue Dahlia on IMDb.

- Veronica Lake And Alan Ladd Teamed Again, by Frank Daugherty. Special to The Christian Science Monitor11 May 1945: 5.

- Houseman p xii-xiii

- Chandler, Raymond (2014-12-02). The World of Raymond Chandler. ISBN 9780385352376. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- Fade-out on Raymond Chandler Lochte, Richard S. Chicago Tribune 14 Dec 1969: 60.

- Houseman p xiii

- SCREEN NEWS: Warners Pay $100,000 Down for 'Hasty Heart' Joan Blondell Gets Top Part Special to THE NEW YORK TIMES. New York Times 19 Feb 1945: 21.

- Houseman p xiii

- Bruccoli p 133

- Houseman p xiii

- "The Blue Dahlia (1946) - Articles - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- Freeman, Judith (2008). The Long Embrace. pp. 227–228. ISBN 9780307472700. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Brucoli p 132

- Bruccoli p 134

- Lenburg, Jeff (2001). Peekaboo: The Story of Veronica Lake. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse. p. 161. ISBN 978-0595192397.

- Hare, William (2012). Pulp Fiction to Film Noir: The Great Depression and the Development of a Genre. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 104. ISBN 9780786466825.

- "Change of Pace in Roles Beckons Veronica Lake: Star to Pause at Career's Crossroads Roles to Shift for Veronica". Schallert, Edwin. Los Angeles Times, 8 July 1945: C1.

- "Action Taken to Curb Outbreak of Rabies." Los Angeles Times 24 May 1945: A12.

- Thumim, Janet (Autumn 1991). "The 'Popular', Cash and Culture in the Postwar British Cinema Industry". Screen. Vol. 32 no. 3. p. 258.

- "The Blue Dahlia". Reviews. Variety. 31 December 1945. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Schwartz, Dennis (22 October 2005). "Blue Dahlia, The". Ozus' World Movie Reviews. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Vagg, Stephen (11 February 2020). "The Cinema of Veronica Lake". Diabolique Magazine.

- "The Blue Dahlia". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "The 19th Academy Awards (1947): Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Loving Re-Creation of The Blue Dahlia SYLVIE DRAKE Times Theater Writer. Los Angeles Times (1923-Current File) [Los Angeles, Calif] 20 Feb 1989: OC_D6.

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00j2j79

Notes

- Bruccoli, Matthew (1976). "Raymond Chandler and Hollywood". The Blue Dahlia: A Screenplay. By Chandler, Raymond. Carbondale. pp. 129–137.

- Houseman, John (1976). "Lost Fortnight, a Memoir". The Blue Dahlia: A Screenplay. By Chandler, Raymond. Carbondale. pp. x–xxi.

External links

- The Blue Dahlia on IMDb

- The Blue Dahlia at AllMovie

- The Blue Dahlia at the TCM Movie Database

- The Blue Dahlia film clip on YouTube

- Review of film at New York Times

- Review of film at Variety

Streaming audio

- The Blue Dahlia on Screen Guild Theater: April 21, 1949