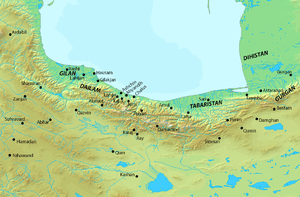

Tabaristan

Tabaristan (Modern Persian طبرستان Ṭabarestān, ultimately from Middle Persian: ![]()

Early history

The Amardians are believed to have been the earliest inhabitants of the region where modern day Mazanderan and Gilan are located. The establishment of the early great kingdom dates back to about the first millennium BCE when the Hyrcanian kingdom was founded with Sadracarta (somewhere near modern Sari) as its capital. Its extent was so large that for centuries the Caspian Sea was called the Hyrcanian Ocean. The first known dynasty were the Faratatians, who ruled some centuries before Christ. During the rise of the Parthians, many of the Amerdians were forced into exile to the southern slopes of the Alborz mountains known today as Varamin and Garmsar, and the Tabaris (who were then living somewhere between today's Yaneh Sar to the north and Shahrud to the south) replaced them in the region.

During the indigenous Gushnaspian dynasty, many of the people adopted Christianity. In 418 CE, the Tapurian calendar (similar to the Armenian and Galeshi) was designed and its use implemented. The Gashnaspians ruled the region until 528 CE, when, after a long period of fighting, the Sasanian King Kavadh I defeated the last Gashnaspian king.

Medieval era

When the Sasanian Empire fell, Yazdegerd III ordered Adhar Valash to cede the dominion to spahbed Gil Gavbara in 645 CE, while western and Southern Gilan and other parts of Gil's domain merged under the name of Tapuria. He then chose Amol as capital of United Tapuria in 647 CE. The dynasty of Gil was known as Gavbareh in Gilan, and as the Dabuyids in eastern Tapuria.

Mazandaranis and Gilaks were among the first groups of Iranians to fight against the Arab invasion. Tabaristan was one of the last parts of Persia to fall to the Muslim Conquest, maintaining resistance until 761 (cf. Khurshid of Tabaristan), when local rulers became vassals of the Abbasid Caliphate.[1] Even after this, Tabaristan remained largely independent of direct control of the Caliphate, and underwent numerous power struggles and rebellions.[2]

In the early 9th century, for example, a Zoroastrian by the name of Mazyar rebelled, taking control of Tabaristan and persecuting Muslims there before his ultimate execution in 839. After this rebellion, the territory was largely restored to the control of the Bavand dynasty, who ruled there as vassals of various successive empires, including the Seljuks, Kwarezmshah, and Mongols.

The area of Tabaristan quickly gained a large Shi'ite element, and by 900, a Zaydi Shi'ite kingdom was established under the Alavids.[3]

In 930, a Zoroastrian commander named Mardavij established the Ziyarid dynasty and briefly conquered much of northern Persia before being betrayed and killed in 935 CE. The Ziyarid dynasty continued to rule over much of Tabaristan until its demise in 1090 CE.

While the Dabuyids controlled the lowlands, the Sokhrayans governed the mountain regions. Vandad Hormozd ruled the region for about 50 years until 1034 CE. After 1125 CE, (the year Maziar was assassinated by subterfuge) an increase in conversion to Islam was achieved, not by the Arab Caliphs, but by the Imam's ambassadors.

Modern era

Tapuria remained independent until 1596, when Shah Abbas I, Mazandarani on his mother's side, incorporated Mazandaran into his Safavid empire, forcing many Armenians, Circassians, Georgians, Kurds and Qajar Turks to settle in Mazandaran. Pietro della Valle, who visited a town near Pirouzcow in Mazandaran in 1618, noted that Mazandarani women never wore the veil and didn't hesitate to talk to foreigners. He also noted the extremely large amount of Circassians and Georgians in the region, and that he had never encountered people with as much civility as the Mazandaranis.

Today, Persia proper, Fars, Mazanderan on the Caspian Sea and many other lands of this empire are all full of Georgian and Circassian inhabitants. Most of them remain Christian to this day, but in a very crude manner, since they have neither priest nor minister to tend them.

— Pietro della Valle

After the Safavid period, the Qajars began to campaign south from Mazandaran with Agha Mohammad Khan who already incorporated Mazandaran into his empire in 1782. On 21 March 1782, Agha Mohammad Shah proclaimed Sari as his imperial capital. Sari was the site of local wars in those years, which led to the transfer of the capital from Sari to Tehran by Fath Ali Shah.

References

- Seif, Asad. "Islam and poetry in Iran". Iran Chamber Society. Iran Chamber Society. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- Inostranzev, M. "Tabaristan". IRANIAN INFLUENCE ON MOSLEM LITERATURE, PART I. Project Gutenburg. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- Goldschmidt, Arthur (2002). A concise history of the Middle East. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. pp. 84. ISBN 0-8133-3885-9.

Sources

- Inostranzev, M. (1918) Iranian Influence on Moslem Literature – Appendix I: Independent Zoroastrian Princes of Tabaristan.

- Khalifa Uthman bin Ghani. Islamic Conquests

- Muhammad B. Al-Hasan B. Isfandiyár (1905) [1216 A.D.]. History of Tabaristán. Leiden, The Netherlands: E.J. Brill.

Further reading

- Webb, Peter (2018). "Tabarestan". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.