Supermarine S.6B

The Supermarine S.6B is a British racing seaplane developed by R.J. Mitchell for the Supermarine company to take part in the Schneider Trophy competition of 1931. The S.6B marked the culmination of Mitchell's quest to "perfect the design of the racing seaplane" and represented the cutting edge of aerodynamic technology for the era.

| S.6B | |

|---|---|

| |

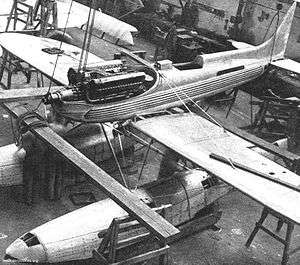

| A Supermarine S.6B under construction, showing the Rolls-Royce R engine | |

| Role | Experimental aircraft, Racing seaplane |

| Manufacturer | Supermarine |

| Designer | R.J. Mitchell |

| First flight | 1931 |

| Introduction | 1931 |

| Primary user | Royal Air Force |

| Number built | 2 |

| Developed from | Supermarine S.6 |

The S.6B was last in a line of racing seaplanes to be developed by Supermarine, followed on from the S.4, S.5 and the S.6.[1] Despite these predecessors having twice won the Schneider Trophy previously, the development of the S.6B was troubled by wavering government support, being promised, withdrawn, and then issued once again following a high-profile public campaign encouraged by Lord Rothermere and a substantial donation by Lady Houston. Once government backing had been secured, there were only nine months remaining until the race, thus Mitchell decided to refine the existing S.6 rather than pursue a clean-sheet design, thus the type's designation of S.6B.

The principal design differences between the S.6 and the S.6B were made in its more powerful Rolls-Royce R engine and redesigned floats, providing much needed additional cooling; minor aerodynamic refinements typically aimed at drag reduction were also implemented. A pair of S.6Bs, serials S1595 and S1596, were constructed for the competition. Flown by members of RAF High Speed Flight, the type competed successfully, winning the Schneider Trophy for Britain. Shortly after the race, S.6B S1596, flown by Flt Lt. George Stainforth, broke the world air speed record, attaining a peak speed of 407.5 mph (655.67 km/h).

Supermarine did not build any successive racing aircraft during this era, largely due to other commitments, including the development of a new fighter aircraft at the request of the British Air Ministry, known as the Type 224. Mitchell and his team's experience in designing high speed Schneider Trophy floatplanes greatly contributing to the development of the later Supermarine Spitfire, an iconic fighter aircraft flown in large numbers by the Royal Air Force; it has been viewed as Britain's most successful interceptor of the Second World War.[2] Both the Spitfire and its Rolls-Royce Merlin engine drew directly upon the S.6B and its Rolls-Royce R engine respectively.

Development

Financing

Despite Prime Minister James Ramsay MacDonald's pledge that government support would be provided for the next British race entrant immediately after Britain's 1929 victory, official funding was withdrawn less than two months later following the Wall Street Crash; the official reason given for the withdrawal that the previous two contests had collected sufficient data on high speed flight, so further expenditure of public money was unwarranted.[3] A further rational given of the government's revised position was that that original purpose in pioneering high speed seaplanes had been satisfied by this point.[4] A committee established by the Royal Aero Club, who were responsible for organising the 1931 race and included representatives from both the aircraft and aero engine industries, was formed to discuss the feasibility of a privately funded entry, but concluded that not only would this be beyond their financial reach, but that the lack of the highly skilled RAF pilots of the High-Speed Flight would pose a severe problem.

The apparent discontinuation of involvement resulted in enormous public disappointment: having won two successive races, a British victory in a third race would secure the trophy outright.[5] As ever active in aviation affairs, Lord Rothermere's Daily Mail group of newspapers launched a public appeal for money to support a British race entrant; in response, several thousand pounds were raised. Lady Houston publicly pledged £100,000.[6][7] The British government also changed its position and announced its support for an entry in January 1931; however, by this point, there were less than nine months left to design, produce and prepare any race entrant. The RAF High Speed Flight was reformed while Mitchell and Rolls-Royce set to work.[8]

Redesign and refinement

_(cropped).jpg)

Mitchell, recognising that he only had seven months to prepare an entry, knew that there was not enough time left to viably design a whole new aircraft from scratch. Instead, he refined the design of the existing Supermarine S.6; the new variant being referred to as the Supermarine S.6B.[6] According to aviation author John D. Anderson Jr, Mitchell retained the majority of the S.6's design, his efforts being principally focused on improving the prospective aircraft's heat dissipation; speaking on a radio broadcast, he later referred to the S.6B as a "flying radiator". Mitchell decided to make use of the aircraft's floats as an additional radiator area; these were considerably larger than those of the S.6, their design being supported by a series of wind tunnel tests performed at the National Physical Laboratory, which was also an area in which government support was helpful to the project. The floats were extended forward by some three feet (0.9 m); while being larger and longer than their predecessor's counterparts, they were streamlined and had a smaller frontal area.[6]

One obvious means of improving the S.6's performance was by obtaining more power from the R-Type engine.[9] Engineers at Rolls-Royce's Derby facility had managed to increase the available power of the engine by 400 hp (298 kW), enabling it to now provide up to 2,300 hp (1,715 kW); however, this level of performance was only guaranteed for a fairly small timeframe.[7] To improve the engine performance, the use of an exotic fuel mix was necessary, as well as the adoption of Sodium-cooled valves.[5] Anderson states that the improvements to the engine and the floats were the only two major innovations of the S.6.[6] Other modifications to the airframe design were mostly limited to minor improvements and some strengthening in order to cope with the increased weight of the aircraft. One cutting-edge feature used in the aircraft's manufacture was the use of flush riveting, a newer and more expensive form of riveting that had drag reduction benefits.[10] Drag reduction was an important priority of Mitchell's refinements, this factor being greatly beneficial to any fast-moving aircraft.[11]

Operational history

Competition and records

Although the British team faced no competitors, due to misfortunes and delays suffered by other intending participants, the RAF High Speed Flight brought a total of six Supermarine Schneider racers to Calshot Spit on Southampton Water for training and practice. These aircraft were: S.5 serial number N219, second at Venice in 1927, S.5 N220, winner at Venice in 1927, two S.6s with new engines and redesignated as S.6As (N247 that won at Calshot in 1929 and S.6A N248, disqualified at Calshot in 1929), and the newly built S.6Bs, S1595 and S1596.[12]

For the competition itself, only the S.6Bs and S.6As were intended to participate. The British plan for the Schneider contest was to have S1595 fly the course alone and, if its speed was not high enough, or the aircraft encountered mechanical failure, then the more-proven S.6A N248 would fly the course. If both S1595 and N248 failed in their attempts, then N247, which was planned to be held in reserve, would be used. The S.6B S1596 was then to attempt the world air speed record. During practice, N247 was destroyed in a takeoff accident, resulting in the death of the pilot, Lieut. G. L. Brinton, R.N.,[13] precluding any other plans with only the two S.6Bs and the sole surviving S.6A prepared to conduct the final Schneider run.[12]

On 13 September 1931, the winning Schneider flight was performed by S.6B S1595, piloted by Flt. Lt. John Boothman, having attained a recorded top speed of 340.08 mph (547.19 km/h) and flown seven perfect laps of the triangular course over the Solent, the strait between the Isle of Wight and the British mainland.[5] Seventeen days later, another historic flight was performed by S.6B S1596, flown by Flt Lt. George Stainforth, having broken the world air speed record by reaching a peak speed of 407.5 mph (655.67 km/h).[14][15][5]

Legacy

The performance of the S.6B and its forerunners served as the foundations for Mitchell to be recognised as a legendary designer of performance aircraft.[16] The S.6B has been hailed as giving the impetus to the development of both the Supermarine Spitfire fighter aircraft and the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine that powered it.[8][17] Neither Mitchell nor Supermarine would produce further racing aircraft for successive competitions as work on the development of a new fighter aircraft at the British government's behest had taken precedence.[18]

Only 18 days following the S.6B's Schneider triumph, the British Air Ministry issued Specification F7/30, which called for a modern all-metal land-based fighter aircraft and sought innovative solutions towards a major improvement in British fighter aircraft; perhaps most significantly, the ministry specifically invited Supermarine to participate. Accordingly, Mitchell's next endeavour after the S.6B was to produce the company's submission to meet this specification, which would be designated the Type 224.[19][17] While the Type 224 would not meet with government approval and ultimately be a disappointment, Supermarine's next project would result in the development of the legendary Spitfire.[20][21][5]

According to author Birch Matthews, the S.6B and Supermarine's racing lineage had played an influence of the design of both the Type 224 and the Spitfire, largely in terms of its aerodynamic cleanness and innovative heat dissipation, there were substantial differences and fresh innovations being incorporated as well.[22] Furthermore, as observed by industrial consultant Philip H. Stevens, the outstanding performance of the S.6B had drawn the attention of not only British military officials and aircraft designers, but internationally as well, influencing new fighter projects in, amongst other nations, both Nazi Germany and the United States.[23]

Aircraft on display

After the completion of the record-breaking flights, both S.6Bs were retired. The Schneider Trophy winning S.6B S1595 was donated to the Science Museum in London, where it resides in an unrestored state.[8]

The ultimate fate of the S1596 is presently unknown. For a short period of time, S1596 did undergo testing at the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment (MAEE) at Felixstowe.[12] Until the 1960s, S.6A N248 was displayed incorrectly as S1596 at Southampton Royal Pier as a visitor attraction.[24]

Specifications (S.6B)

Data from Supermarine Aircraft since 1914.[25]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 28 ft 10 in (8.79 m) including floats

- 25 ft 3 in (8 m) fuselage only

- Wingspan: 30 ft 0 in (9.14 m)

- Height: 12 ft 3 in (3.73 m)

- Wing area: 145 sq ft (13.5 m2)

- Airfoil: RAF 27[26]

- Empty weight: 4,590 lb (2,082 kg)

- Gross weight: 6,086 lb (2,761 kg)

- Powerplant: × Rolls-Royce R V-12 liquid-cooled piston engine, 2,350 hp (1,750 kW) at 3,200 rpm

- Propellers: 2-bladed fixed-pitch metal propeller

Performance

- Maximum speed: 407.5 mph (655.8 km/h, 354.1 kn) (World speed record)

- 390 mph (340 kn; 630 km/h) normal, in level flight

- Alighting speed: 95 mph (83 kn; 153 km/h)

- Wing loading: 42 lb/sq ft (210 kg/m2)

- Power/mass: 0.386 hp/lb (0.635 kW/kg)

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

References

Notes

- Price 1977, p. 11.

- Nichols 1996, p. 9.

- Andrews and Morgan 1987, pp. 194–195.

- Anderson 2018, pp. 131–132.

- "Supermarine S6 and S6B." BAE Systems, Retrieved: 28 May 2019.

- Anderson 2018, p. 132.

- Ferdinand Andrews and Morgan 1981, p. 8.

- Winchester 2005, p. 238.

- Green 1967, pp. 745–746.

- Anderson 2018, p. 133.

- Matthews 2001, p. 44.

- Green 1967, p. 744.

- "Death of Lt. Brinton." Flight, 21 August 1931.

- Price 1977, p. 12.

- Lionel Robert James 2003, p. 127.

- Anderson 2018, pp. 132–133.

- Ferdinand Andrews and Morgan 1981, p. 211.

- Matthews 2001, p. 45.

- Anderson 2018, pp. 134–135.

- Anderson 2018, pp. 137–138.

- Bader 1973, p. 45.

- Matthews 2001, pp. 44–46.

- Stephens 2002, p. 166.

- "Royal Pier, Southampton, Hampshire." Archived 27 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine The Heritage Trail, 1998–2008. Retrieved: 17 September 2009.

- Andrews, C.F.; Morgan, Eric B. (2003). Supermarine Aircraft Since 1914 (2nd Revised ed.). London: Putnam Aeronautical. pp. 174–203.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

Bibliography

- Anderson, John D. Jr. "The Grand Designers." Cambridge University Press, 2018. ISBN 0-5218-1787-0.

- Andrews, C.F. and E.B. Morgan. Supermarine Aircraft since 1914, 2nd edition. London: Putnam, 1987. ISBN 0-85177-800-3.

- Bader, Douglas. "Fight for the Sky: the Story of the Spitfire and the Hurricane." Doubleday, 1973. ISBN 0-3850-3659-0.

- Ferdinand Andrews, Charles and Eric B. Morgan. "Supermarine aircraft since 1914." Putnam, 1981. ISBN 0-3701-0018-2.

- Green, William, ed. "Supermarine's Schneider Seaplanes." Flying Review International, Volume 10, No. 11, July 1967.

- Lionel Robert James, Cyril. "Letters from London: Seven Essays by C.L.R. James." Signal Books, 2003. ISBN 1-9026-6961-4.

- Matthews, Birch. "Race with the Wind: How Air Racing Advanced Aviation." MBI Publishing Company, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-0729-6.

- McKinstry, Leo. Spitfire – Portrait of a Legend. London: John Murray, 2007. ISBN 0-7195-6874-9.

- Nichols, Mark, ed. Spitfire 70: Invaluable Reference to Britain's Greatest Fighter, Flypast Special. Stamford, Linc, UK: Key Publishing, 1996.

- Price, Alfred. Spitfire: A Documentary History. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1997. ISBN 0-684-16060-9.

- Robertson, Bruce. Spitfire: Story of a Famous Fighter. London: Harleyford, 1962. ISBN 0-900435-11-9.

- Shelton, John (2008). Schneider Trophy to Spitfire – The Design Career of R.J. Mitchell (Hardback). Sparkford: Hayes Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84425-530-6.

- Spick, Mike. Supermarine Spitfire. New York: Gallery Books, 1990. ISBN 0-8317-1403-4.

- Stephens, Philip H. Industrial design: a practising professional. Hard Pressed Pub., 2002. ISBN 0-9667-3750-4.

- Winchester, Jim. "Supermarine S.6B". Concept Aircraft: Prototypes, X-Planes and Experimental Aircraft. Kent, UK: Grange Books plc., 2005. ISBN 978-1-84013-809-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Supermarine S.6B. |

- Air racing history

- RJ Mitchell: A life in aviation, 1931 Schneider Trophy, Cowes

- 16mm B&W Newsreel footage of 1931 Schneider Trophy

- "The Supermarine S.6b", Popular Mechanics, December 1931, complete detailed cutaway drawings of S.6B

- Photo walk around by Don Busack of the actual Schneider Trophy winning Supermarine S.6B displayed at the Science Museum, London.

- "The Supermarine S.6B Monoplane." Flight, 2 October 1931, pp. 981–982.