Stanley Mosk

Morey Stanley Mosk (September 4, 1912 – June 19, 2001) was an Associate Justice of the California Supreme Court for 37 years (1964–2001), and holds the record for the longest-serving justice on that court. Before sitting on the Supreme Court, he served as Attorney General of California and as a trial court judge, among other governmental positions. Mosk was the last Justice of the California Supreme Court to have served in non-judicial elected office before his appointment to the bench. The Los Angeles County Courthouse is named after him.[1]

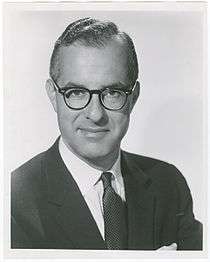

Stanley Mosk | |

|---|---|

Mosk as Attorney General in 1960 | |

| Associate Justice of the California Supreme Court | |

| In office September 1, 1964 – June 19, 2001 | |

| Appointed by | Pat Brown |

| Preceded by | Roger J. Traynor |

| Succeeded by | Carlos R. Moreno |

| Attorney General of California | |

| In office 1959–1964 | |

| Governor | Pat Brown |

| Preceded by | Pat Brown |

| Succeeded by | Thomas C. Lynch |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Morey Stanley Mosk September 4, 1912 San Antonio, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | June 19, 2001 (aged 88) San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Helen Edna Mitchell (m. 1936; death 1981) Susan Jane Hines (m. 1982; div. 1995) Kaygey Kash (m. 1995) |

| Children | Richard M. Mosk |

| Alma mater | University of Chicago (B.A.) Southwestern University School of Law (LL.B) |

Early life and career

Mosk was born in San Antonio, Texas. His parents moved when he was three years old, and he grew up in Rockford, Illinois. His parents, Paul and Minna (Perl) Mosk,[2] were Reform Jews (of Hungarian and German origin, respectively) who did not believe in strict religious observances.[3] Since Rockford sits next to the Wisconsin border, Mosk's parents followed Wisconsin politics and were strong supporters of Progressive Wisconsin Senator Robert M. La Follette Sr.[4] Mosk graduated from the University of Chicago in 1933 with a bachelor's degree in philosophy.[5]

Mosk's life was strongly affected by the Great Depression. Because his father's business in Rockford was floundering, his parents and brother relocated to Los Angeles, and Mosk followed them after graduating from college, as they could not afford to support him in further studies in Chicago.[6][5] At the time, it was possible to use the last year of a bachelor's degree as the first year of a three-year law degree program, so while living with his parents, Mosk was able to obtain a law degree in two years. He earned a LL.B from Southwestern University School of Law in 1935 and was admitted to the bar that same year.[7][8] Thanks to the Depression, no major Los Angeles firms were hiring. Mosk opened his solo practice, and shared an office with four other solos, each maintaining separate practices.[9] During those difficult years, Mosk was a general practitioner who took whatever walked in the door.[10]

While practicing law, Mosk occasionally assisted the Democratic politician Culbert Olson with campaigning,[11] and in 1939 was given the job of executive secretary to Olson,[12] the first Democrat elected Governor of California in the 20th-century.[13][14] During Olson's last days in office, after his defeat for re-election by Republican Earl Warren, he appointed Mosk a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge at the age of 31, the youngest in the state.[15][16] Mosk faced opposition at his first retention election (California is a modified Missouri Plan state), but prevailed.[17][18]

In March 1945, Mosk left the Superior Court to volunteer for service in the U.S. Army during World War II as a private, but spent most of the war in a transportation unit in New Orleans and never went abroad.[19][20] After honorable discharge in September 1945, he returned to California and resumed his judicial career.[21] On October 18, 1945, actress Ava Gardner married bandleader Artie Shaw at Mosk's house.[22] In 1947, as a Superior Court judge, he declared the enforcement of racial restrictive covenants unconstitutional before the Supreme Court of the United States did so in Shelley v. Kraemer.[23][24] He also presided over many widely reported cases.

Attorney General of California

In 1958, he was elected Attorney General of California by the largest margin of any contested election in the country that year, and was the first person of Jewish descent to serve as a statewide executive branch officer in California. In 1962, he was re-elected by a large margin. He served as the California National Committeeman to the Democratic National Committee and was an early supporter of John F. Kennedy for President. He remained close to the Kennedy family.

As attorney general for nearly six years, he issued approximately two thousand written opinions, handled a series of landmark cases, and on January 8, 1962, appeared before the U.S. Supreme Court in Arizona v. California.[25]

Mosk established the Attorney General's Civil Rights Division and successfully fought to force the Professional Golfers' Association of America to amend its bylaws denying access to minority golfers.[26][27] He also established Consumer Rights, Constitutional Rights, and Antitrust divisions. As California's chief law enforcement officer, he sponsored legislation creating the California Commission on Peace Officers' Standards and Training (POST).[28]

Mosk also commissioned a study of the resurgence of right-wing extremism in California, which famously characterized the secretive John Birch Society as a "cadre" of "wealthy businessmen, retired military officers and little old ladies in tennis shoes."[29][30]

State Supreme Court Justice

While an early favorite to be elected to the United States Senate after the death of incumbent Clair Engle, Mosk was appointed to the California Supreme Court in September 1964 by Governor Edmund G. "Pat" Brown to succeed the elevated Roger J. Traynor.[31][32][33] Mosk was retained by the electorate in 1964, and to three full twelve-year terms from 1974.[34]

Although Mosk was a self-described liberal, he often displayed an independent streak that sometimes surprised his admirers and critics alike.[35] For example, in Bakke v. Regents of the University of California,[36] Mosk ruled that the minority admissions program at the University of California, Davis violated the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution. This decision was affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978), which, unlike Mosk's opinion, held that race could be factored in admissions to promote ethnic diversity. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed with Mosk in rejecting racial quotas. He also voted to uphold the constitutionality of a parental consent for abortion law—a law ultimately struck down by a majority of the court.[37]

Although personally opposed to the death penalty, Mosk voted to uphold death penalty convictions on a number of occasions. He believed he was obligated to enforce laws properly enacted by the people of the state of California, even though he personally did not approve of such laws. One example of how he articulated his beliefs is his concurrence in In re Anderson, 69 Cal. 2d 613 (1968):[38]

In my years as Attorney General of California (1959-1964), I frequently repeated a personal belief in the social invalidity of the death penalty ... Naturally, therefore, I am tempted by the invitation of petitioners to join in judicially terminating this anachronistic penalty. However, to yield to my predilections would be to act wilfully 'in the sense of enforcing individual views instead of speaking humbly as the voice of law by which society presumably consents to be ruled. ...' [Citation.] As a judge, I am bound to the law as I find it to be and not as I might fervently wish it to be.

One of Mosk's contributions to jurisprudence was development of the constitutional doctrine of "independent state grounds." This is the concept that individual rights are not dependent solely on interpretation of the U.S. Constitution by the U.S. Supreme Court and other federal courts, but also can be found in state constitutions, which often provide greater protection for individuals.[39]

Although Mosk was widely viewed as a liberal, he was not a close ally of controversial Chief Justice Rose Bird. As a result of that and his independence, he won reelection to the court in 1986 with 75% of the vote while Bird and two other justices closely allied with her were defeated for reelection. In November 1998, at age 86, Mosk was retained by the electorate for another twelve-year term.[34]

Mosk served on the high court until his death in 2001, having surpassed Justice John W. Shenk to become the longest-serving justice in the history of the Court in 1999.[40] Mosk authored many significant opinions, some of which have been included in law school casebooks. In 1999, Albany Law School Professor Vincent Martin Bonventre described Mosk as, "An institution, an icon, a trailblazer, a legal scholar, a constitutional guardian, a veritable living legend of the American judiciary, . . . one of the most influential members in the history of one of the most influential tribunals in the western world."[41]

Legacy

The Stanley Mosk Courthouse, which is the main civil courthouse of the Superior Court of Los Angeles County, is located at 111 North Hill Street in Los Angeles. It is part of the Civic Center complex which includes the County of Los Angeles Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration. The courthouse is often seen in the Perry Mason TV series, when Perry parks his car on Hill Street to go inside the building.

The Stanley Mosk Library & Courts Building is located on the Capitol Mall in Sacramento, California and is the home of the California Court of Appeal for the Third District.[42]

A billboard for Mosk's reelection campaign for Attorney General is featured during the final car chase scene in the 1963 film It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, which was filmed in Long Beach, California in 1962.

Personal life

Mosk married three times. On September 27, 1936, he married Helen Edna Mitchell in Beverly Hills, California, and they had one son, Richard.[43] After her death on May 22, 1981, he remarried on August 27, 1982, to Susan Jane Hines in Reno, Nevada, who was more than 30 years his junior.[43] They divorced and on January 15, 1995, Mosk married Kaygey Kash, a long-time friend.[43]

His son, Richard M. Mosk, became an attorney and Justice of the California Court of Appeal, Second District.[44]

References

- "Stanley Mosk Courthouse / Los Angeles County Courthouse". Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- Braitman, Jacqueline R.; Uelmen, Gerald F. (14 November 2012). Justice Stanley Mosk: A Life at the Center of California Politics and Justice. ISBN 9781476600710.

- Hon. Stanley Mosk, Oral History Interview (Berkeley: California State Archives Regional Oral History Office, 1998), 1-3.

- Mosk Oral History Interview, 3.

- Mosk Oral History Interview, 8.

- Morain, Dan (January 26, 1986). "Stanley Mosk: Will Dean of High Court Hang It Up?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- "Supreme Court Justice to Speak at LMC". Los Medanos College Experience. 27 (9). California Digital Newspaper Collection. 23 October 1987. p. 1. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Mosk Oral History Interview, 8-9.

- Mosk Oral History Interview, 9.

- Mosk Oral History Interview, 12.

- "Brown Urges Support of Democratic Ticket". San Bernardino Sun (45). California Digital Newspaper Collection. 13 October 1938. p. 14. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Mosk Oral History Interview, 13-14.

- Dunlop, Jack W. (10 August 1939). "Politically Speaking". Healdsburg Tribune, Enterprise and Scimitar (99). California Digital Newspaper Collection. UPI. p. 4. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- "Secretary Force Gets New Member". Madera Tribune (94). California Digital Newspaper Collection. 19 August 1939. p. 4. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- "Olson Has Number of Appointments to Make". San Bernardino Sun (49). California Digital Newspaper Collection. Associated Press. 12 November 1942. p. 5. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- "L.A. Judges Named". San Bernardino Sun (49). California Digital Newspaper Collection. 3 January 1943. p. 12. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- "Court Bars Seven Candidates from Using CIO Funds". San Bernardino Sun (51). California Digital Newspaper Collection. United Press. 4 November 1944. p. 1. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- "FDR Triumphs". Corsair. 16 (9). California Digital Newspaper Collection. 7 November 1944. p. 1. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- "Judge Mosk Resigns". San Bernardino Sun (51). California Digital Newspaper Collection. United Press. 6 March 1945. p. 1. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Mosk Oral History Interview, 15-16.

- "In the Shadows". San Bernardino Sun (52). California Digital Newspaper Collection. United Press. 16 September 1945. p. 10. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- "Bandleader Artie Shaw Marries Ava Gardner". San Bernardino Sun (52). California Digital Newspaper Collection. United Press. 18 October 1945. p. 1. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- "Court Refuses to Bar Negroes from Wilshire". San Bernardino Sun. 45 (47). California Digital Newspaper Collection. United Press. 24 October 1947. p. 1. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- "Racial Eviction Suits Dismissed". San Bernardino Sun. 54 (54). California Digital Newspaper Collection. United Press. 1 November 1947. p. 1. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Arizona v. California Archived 2005-11-15 at the Wayback Machine, 373 U.S. 546 (1963). Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- "PGA opens its doors to Negroes, world golfers". Florence Times. Alabama. Associated Press. November 10, 1961. p. 4, section 2.

- "PGA group abolishes 'Caucasian'". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Florida. Associated Press. November 10, 1961. p. 22.

- California Attorney General web page: AG.ca.gov

- "The Harmless Ones", Time, August 11, 1961. Paid subscription access.

- California Attorney General (1961). Report on the John Birch Society. Worldcat.org. OCLC 19652378.

- "World Wire". Madera Tribune (207). California Digital Newspaper Collection. UPI. 3 March 1964. p. 1. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- "Brown May Tap Mosk For Court". Madera Tribune (64). California Digital Newspaper Collection. UPI. 11 August 1964. p. 2. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- "Brown Names Mosk Attorney General To Supreme Court; Traynor Is Chief". Desert Sun (9). California Digital Newspaper Collection. UPI. 14 August 1964. p. 1. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Uelmen, Gerald F. (1999). "Justice Stanley Mosk", 65 Albany Law Review 857, fn. 1. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Chiang, Harriet; Egelko, Bob (June 20, 2001). "Stanley Mosk / 1912-2001 / State Supreme Court justice dies at 88 / Ex-California attorney general, 'a giant in the law,' had longest tenure". San Francisco Gate. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Bakke v. Regents of the University of California, 18 Cal. 3d 34 (1976). Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- American Academy of Pediatrics v. Lungren, 16 Cal.4th 307 (1997). Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- In re Anderson, 69 Cal. 2d 613 (1968). Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Gerawan Farming, Inc. v. Lyons, 24 Cal.4th 468, 489-496, 510-515 (2000); Sands v. Morongo Unified School District, 53 Cal.3d 863, 905-907 (1991) (Mosk, J., concurring); People v. Pettingill, 21 Cal.3d 231, 247-248 (1978); People v. Brisendine, 13 Cal.3d 528, 545, 548-552 (1975); Stanley Mosk, "Brennan Lecture: States' Rights -- And Wrongs," 72 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 552, 559-565 (1997); Stanley Mosk, State Constitutionalism: Both Liberal and Conservative, 63 Tex. L. Rev. 1081, 1087-1093 (1985).

- "Stanley Mosk, 88, Long a California Supreme Court Justice". New York Times. Associated Press. June 21, 2001. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Vincent Martin Bonventre, Editor's Foreword to State Constitutional Commentary, 62 Albany Law Review 1213, 1213 (1999).

- Dedication of the Stanley Mosk Library and Courts Building. California State Courts. Retrieved July 24, 2017.

- Braitman, Jacqueline R.; Uelmen, Gerald F. (2013). Justice Stanley Mosk: a life at the center of California politics and justice. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. pp. 26, 236–237. ISBN 978-1476600710. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Dolan, Maura (April 19, 2016). "Richard M. Mosk dies at 76; California Court of Appeal justice and Warren Commission staffer". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

Selected publications

Books

- Mosk, Stanley (1995). Democracy in America-- Day by Day. New York, NY: Vantage Press. ISBN 0533112044.

Articles

- Mosk, Stanley (1997). "Brennan Lecture: States' Rights -- And Wrongs" (PDF). N.Y.U. L. Rev. 72 (3): 552–566. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Mosk, Stanley (1993). "Nothing Succeeds Like Excess". Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 26 (4): 981. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Mosk, Stanley (1991). "Gideon Kanner". Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 24 (3): 516. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

Further reading

- Uelmen, Gerald F. (June 22, 2002). "Tribute to Justice Stanley Mosk", 65 Albany Law Review 857. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Braitman, Jacqueline R.; Uelmen, Gerald F. (2013). Justice Stanley Mosk: a life at the center of California politics and justice. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-1476600710. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

Video

- Oral argument before the California Supreme Court (October 11, 1991), on the constitutionality of proposition 140 which would impose term limits on elected officials. C-Span.org.

External links

- Stanley Mosk. California Supreme Court Historical Society.

- Stanley Mosk, Oral History interview (PDF). Regional Oral History Office, University of California, Berkeley, 1998.

- Opinions authored by Stanley Mosk. Courtlistener.com.

- Stanley Mosk at U.S. Supreme Court. Oyez.com.

- Past & Present Justices. California State Courts.

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Pat Brown |

Attorney General of California 1959–1964 |

Succeeded by Thomas C. Lynch |

| Preceded by Roger J. Traynor |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of California 1964–2001 |

Succeeded by Carlos R. Moreno |