St Mark's Campanile

St Mark's Campanile (Italian: Campanile di San Marco) is the bell tower of St Mark's Basilica in Venice, Italy. It is the tallest structure in Venice and is colloquially termed "el paròn de casa" (the master of the house). It is one of the most recognizable symbols of the city.

| |

| Location | Saint Mark's Square Venice Italy |

|---|---|

| Height | 98.6 metres (323 ft) |

| Built | early tenth century–1514 |

| Rebuilt | 1902–1912 |

| Architect | Giorgio Spavento (belfry) |

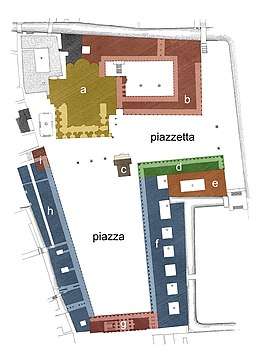

Located in Saint Mark’s Square, Venice’s former governmental centre, the campanile was initially built as a watch tower to sight approaching ships and protect the entry to the city. It also served as a landmark to guide Venetian ships safely into harbour. Construction began in the early tenth century. The tower was slowly raised in height and acquired a belfry and a spire in the twelfth century. In the fourteenth century the spire was gilded, making the tower visible to distant ships in the Adriatic.

The tower is 98.6 metres (323 ft) tall, and stands alone in a corner of St Mark's Square, near the front of the basilica. It has a simple form, the bulk of which is a fluted brick square shaft, 12 metres (39 ft) wide on each side and 50 metres (160 ft) tall, above which is a loggia surrounding the belfry, housing five bells. The belfry is topped by a cube, alternate faces of which show the Lion of St. Mark and the female representation of Venice (la Giustizia: Justice). The tower is capped by a pyramidal spire, at the top of which sits a golden weathervane in the form of the archangel Gabriel. The campanile reached its present form in 1514.

The current tower was reconstructed in its present form in 1912 after the original collapsed in 1902.

Historical background

The Magyar raids into northern Italy in 898 and again in 899 resulted in the plundering and brief occupation of the important mainland cities of Cittanova, Padua, and Treviso as well as several smaller towns and settlements in and around the Venetian Lagoon.[1] Although the Venetians ultimately defeated the Magyars on the Lido of Albiola on 29 June 900 and repelled the incursion,[2] Venice remained vulnerable by way of the deep navigable channel that allowed access to the harbour from the sea. In particular, the young city was threatened by the Slavic pirates who routinely menaced Venetian shipping lanes in the Adriatic.[3]

A series of fortifications was consequently erected during the reign of Doge Pietro Tribuno (887–911) to protect Venice from invasion by sea.[note 1] These fortifications included a wall that started at the rivulus de Castello (Rio del Palazzo), just east of the Doge’s Castle, and eventually extended along the waterfront to the area occupied by the early Church of Santa Maria Iubanico.[note 2] In addition, an iron chain that could be pulled taut across the Grand Canal and impede further access was installed at the height of San Gregorio. The exact location of the wall has not been determined nor is its duration beyond the moment of crisis indisputable.[note 3][note 4] Integral to this defensive network, a massive watch tower was built in Saint Mark’s Square. Begun around 901–902, it was also intended to serve as a point of reference to guide Venetian ships safely into the harbour which at that time occupied a substantial part of the area corresponding to the present-day piazzetta.[4][5]

Construction

Tower

The defensive system begun under Pietro Tribuno was only provisional, and construction may have been limited to the reinforcement of pre-existing structures. Mediaeval chronicles attribute the building of the tower, principally the foundation, to his immediate successors, Orso II Participazio (912–932) and Pietro II Candiano (932–939). Delays were likely due to the difficulty in locating and importing building materials from the mainland as well as developing suitable construction techniques.[6][7][note 5] Fabrication of the actual tower seems to have begun during the brief reign of Pietro Participazio (939–942) but did not progress far.[7] Political stife during the ensuing reigns of Pietro III Candiano (942–959) and, particularly, Pietro IV Candiano (959–976) precluded further work.[8]

Under Pietro I Orseolo (976–978), construction resumed, and it advanced considerably during the reign of Tribuno Memmo (979–991). No further additions were made to the tower until the time of Domenico Selvo (1071–1084), an indication that it had reached a serviceable height and could be used to control access to the city.[9] Selva increased the height in correspondence to the fifth of the eight windows.[10] Doge Domenico Morosini (1147–1156) then raised the height to the actual level of the belfry and is credited with the construction of the bell tower. His portrait in the Doge's Palace shows him together with a scroll that lists the significant events of his reign, among which is the construction of the bell tower: "Sub me admistrandi operis campanile Sancti Marci construitur…".[11]

Belfry and spire

The first belfry was added under Vitale II Michiel (1156–1172). It was surmounted by a pyramidal spire in wood that was sheathed with copper plates.[12] Around 1329, the belfry was restored and the spire reconstructed. The spire itself was particularly prone to fire due to the wooden framework. It burned when lighting struck the tower on 7 June 1388, but it was nevertheless rebuilt in wood. On this occasion, the copper plates were covered in gold leaf, rendering the tower visible to distant ships in the Adriatic.[13] The spire was once again destroyed in 1403 when flames from a bonfire lit to illuminate the tower in celebration of the Venetian victory over the Genoese at the Battle of Modon enveloped the wooden frame.[13] It was rebuilt between 1405 and 1406.[14]

Lightning again struck the tower during a violent storm on 11 August 1489, setting ablaze the spire which eventually crashed into the square below. The bells fell to the floor of the belfry, and the masonry of the tower itself cracked.[15] In response to this latest calamity, the procurators of Saint Mark de supra, the government officials responsible for the public buildings around Saint Mark’s Square, deliberated to rebuild the belfry and spire completely in masonry so as to prevent future fires. The commission was given to their proto (consultant architect and buildings manager), Giorgio Spavento. Although the design was submitted within a few months, financial constraints in the period of recovery from the wars in Lombardy against Milan (1423–1454) delayed execution. Instead, Spavento limited repairs to the structural damage to the tower. A temporary clay-tile roof was placed over the belfry, and the bells that were still intact were rehung. The outbreak in 1494 of the Italian wars for the control of the mainland precluded any further action.[16]

On 26 March 1511, a violent earthquake further damaged the fragile structure and opened a long fissure on the northern side of the tower, making it necessary to immediately intervene. Upon the initiative of procurator Antonio Grimani, the temporary roof and the belfry were removed and preparations were made to finally execute Spavento's design.[17] The work was carried out under the direction of Pietro Bon who had succeeded Spavento as proto in 1509.[18][note 6] To finance the construction, the procurators sold unclaimed objects in precious metals that had been deposited in the treasury of Saint Mark's in 1414. By 1512, the tower itself had been completely repaired, and work began on the new belfry in Istrian stone.

The four sides of the brick attic above have high-relief sculptures in contrasting Istrian stone. The eastern and western sides have allegorical figures of Venice, presented as a personification of Justice with the sword and the scales. She sits on a throne supported by lions on either side in allusion to the throne of Solomon, the king of ancient Israel renowned for his wisdom and judgement.[19] This theme of Venice as embodying, rather than invoking, the virtue of Justice is common in Venetian state iconography and is recurrent on the façade of the Doge’s Palace.[20] The remaining sides of the attic have the lion of Saint Mark, the symbol of the Venetian Republic.

The completion of work was celebrated on 6 July 1513 when a wooden statue of the archangel Gabriel, plated in copper and gilded, was placed at the top of the spire. In his diary, Marin Sanudo recorded the event: "On this day, a gilded copper angel was hoisted above Saint Mark’s Square at four hours before sunset to the sound of trumpets and fifes, and wine and milk were sprayed from above as a sign of merriment" ("In questo zorno, su la piazza di San Marco fo tirato l’anzolo di rame indorado suso con trombe e pifari a hore 20; et fo butado vin e late zoso in segno di alegrezza").[21][22]

A novelty with respect to the earlier tower, the statue functioned as a weather vane, turning so that it always faced into the wind.[23] Francesco Sansovino suggested in his guide to the city, Venetia città nobilissima et singolare (1581), that the idea of a weather vane atop the new tower derived from Vitruvius’ description of the Tower of the Winds in Athens which had a bronze triton mounted on a pivot.[24][25] But the specific choice of the archangel Gabriel was meant to recall the legend of Venice’s foundation on the 25 March 421, the feast of the Annunciation.[note 7] In Venetian historiography, the legend, traceable to the thirteenth century, conflated the beginning of the Christian era with the birth of Venice as a Christian republic and affirmed Venice's unique place and role in history as an act of divine grace.[26] As a construct, it is expressed in the frequent representations of the Annunciation throughout Venice, most notably on the façade of Saint Mark's Basilica and in the reliefs by Agostino Rubini at the base of the Rialto Bridge, depicting the Virgin Mary opposite the archangel Gabriel.[27]

Loggetta

In the fifteenth century, the procurators of Saint Mark de supra erected a covered exterior gallery attached to the bell tower. It was a lean-to wooden structure, partially enclosed, that served as a gathering place for nobles whenever they came to the square on government business. It also provided space for the procurators who occasionally met there and for the sentries who protected the entry to the Doge's Palace whenever the Great Council was in session.

Over time, it was repeatedly damaged by falling masonry from the bell tower as a result of storm and earthquake but was repaired after each incident. However, when lightning struck the bell tower on 11 August 1537 and the loggia underneath was once again damaged, it was decided to completely rebuild the structure. The commission was given to the sculptor and architect Jacopo Sansovino, the immediate successor to Bon as proto of the procurators of Saint Mark de supra. It was completed in 1546.

The remaining three sides of the bell tower were covered with wooden lean-to stalls, destined for retail activities. These were an additional source of revenue for the procurators of Saint Mark de supra and were leased in order to finance the maintenance of the buildings in the square. The lean-to stalls were removed in 1873.

Later history

Throughout its history, the bell tower remained subject to damage from storms. Lightning struck in 1548, 1562, 1565, and 1567.[28][29] On each occasion, repairs were carried out under the direction of Jacopo Sansovino, responsible as proto for the maintenance of the buildings administered by the procurators of Saint Mark de supra, including the bell tower. The work, funded from the accounts of the procurators, was typically executed by carpenters provided by the Arsenal, the government shipyards.[30] The tower was damaged twice in 1582.[31][32]

In the following centuries, it was repeatedly necessary to intervene and repair the damage caused by lightning. In 1653, Baldassarre Longhena took up repairs after lightning struck, having become proto in 1640. The damage must have been extensive on this occasion, given the repair cost of 1230 ducats.[33] Significant work was also necessary to repair damage done after lightning struck on 23 April 1745, causing some of the masonry to crack and killing four people in the square as a result of falling stonework.[34] The campanile was again damaged by lightning in 1761 and 1762. Repair costs on the second occasion reached the considerable sum of 3329 ducats.[35] Finally, on 18 March 1776, the physicist Giuseppe Toaldo, professor of astronomy at the University of Padua, installed a lightning rod, the first in Venice.[36][37][35]

Periodic work was also needed to repair damage from wind and rain erosion. The original statue of the Archangel Gabriel was replaced in 1557 with a smaller version. After numerous restorations, this was in turn substituted in 1820 by a statue designed by Luigi Zandomeneghi.

The tower remained of strategic importance to the city. Access to visiting foreign dignitaries was allowed only by the Senate and only at high tide when it was not possibile to distinguish the navigable channels in the lagoon. On 21 August 1609, Galileo Galilei demonstrated his telescope to the procurator Antonio Priuli and other nobles from the belfry. Three days later, the telescope was presented to doge Leonardo Donato from the loggia of the Doge's Palace.[38]

Bells

History

A bell was most likely first installed in the tower during the reign of Doge Vitale II Michiel. However, documents that attest to the presence of a bell are traceable only from the thirteenth century. A deliberation of the Great Council, dated 8 July 1244, established that the bell to convene the council was to be rung in the evening if the council was to meet the following morning and in the early afternoon if the meeting was scheduled for the evening of the same day. There is a similar reference to the bell in the statute of the ironmongers' guild, dating to 1271.[39]

Over time, the number of bells varied. In 1489, there were at least six. Four were present in the sixteenth century until 1569 when a fifth was added. Beginning in 1678 the bell brought to Venice from Crete after the island was lost to the Ottoman Turks, called the Campanon da Candia, hung in the tower. But when it fell to the floor of the belfry in 1722, it was not resuspended. After this time, five bells remained.[40] These were named (from smallest to largest) Maleficio (also Renghiera or Preghiera), Trottiera (also Dietro Nona), Meza-terza (also Pregadi), Nona, and Marangona.[41][42][43][note 8]

The original Marangona and Renghiera, together with the Campanon da Candia and other bells from former churches, were recast by Domenico Canciani Dalla Venezia into two larger bronze bells between 1808 and 1809. But these were melted with the Meza-terza, Trottiera, and Nona in 1820, again by Dalla Venezia, to create a new series of five bells.[44] Of these bells, only the Marangona survived the collapse of the bell tower in 1902.[45]

Functions

In various combinations, the bells indicated the times of the day and coordinated activities throughout the city. Four of the bells also had specific functions in relation to the activities of the Venetian government.

Times of the day

At dawn, with the first appearance of daylight, the Meza-terza rang (16 series of 18 strokes). The Marangona followed at sunrise (16 series of 18 strokes). Then, after a half hour, the Meza-terza rang continuously for a half hour. An hour then ensued at the end of which the Marangona marked the beginning of the work day (25 series of 26 strokes). The bell, the largest, derived its name from this particular function in reference to the marangoni (carpenters) who worked in the Arsenal, the government shipyards.[46]

At midday, the Nona sounded (16 series of 18 strokes). Its name was associated with the Ninth Hour (Nones), the moment of the liturgical mid-afternoon prayer. A half hour later, the Trottiera rang continuously for 30 minutes: from this particular function, the Trottiera was also termed Dietro Nona (behind, or after, Nona). An hour later (two hours after midday), the Nona, followed by the Marangona, rang to mark the vespertine Ave Maria.[47]

The Marangona rang (15 series of 16 strokes) at sunset which corresponded to 24 hours and the end of the day. An hour later, the Meza-terza rang for 15 minutes, followed 12 minutes later by the Nona for 15 minutes. After another 12 minutes, the Marangona struck for 6 minutes, ending at two hours after sunset.[48]

Midnight was marked by the ringing of the Marangona (16 series of 18 strokes).[48]

Public executions

The smallest bell, known alternatively as the Renghiera, Maleficio, or Preghiera, signalled public executions. It had previously been located in the Doge’s Palace and is mentioned in connection with the execution for treason of Doge Marin Falier in 1355. In 1569, it was moved to the tower. The earliest name Renghiera derived from renga (harangue) in reference to the court proceedings within the Palace. The alternative name of Maleficio, from malus (evil, wicked), recalled the criminal act, whereas Preghiera (prayer) invoked supplications for the soul of the condemned.[49] After the execution, the Marangona was rung for a half hour and then the Meza-terza.[50]

Convocation of the Great Council

The Marangona announced the sessions of the Great Council.[51] In the event that the council was to meet in the afternoon, the Trottiera first rang for 15 minutes, immediately after Third Hour (Terce). After midday, the Marangona resounded (9 series of 50 strokes followed by 5 of 25). The Trottiera then rang continuously for a half hour as a second call for the members of the Great Council, signalling the need to quicken the pace. The name of the bell originated when horses were used in the city. The ringing of the Trottiera was therefore meant to signal the need to proceed at a trot. When the bell ceased, the doors of the council hall were closed and the session began. No latecomers were admitted. Whenever the Great Council convened in the morning, the Trottiera rang the previous evening for 15 minutes after the Marangona marked the end of the day. The Marangona was then rung in the morning, with the prescribed series of strokes, followed by the Trottiera.[47]

Convocation of the Senate

The meetings of the Venetian Senate were announced by the Trottiera which rang for 12 minutes. It was then joined by the Meza-terza, and both bells rang together for 48 minutes. The Meza-terza was also known as the Pregadi in reference to the early name of the Senate when members were 'prayed' (pregadi) to attend.[52]

Holy days and events

On solemnities and certain feast days, all the bells rang in plenum. The bells also rang in unison for three days, until three hours after sunset, to mark the election of the doge and the coronation of the pope. On these occasions, they were rapidly hammered. Two hundred lanterns were also arranged in four tiers at the height of the belfry in celebration.[50]

To announce the death of the doge and for the funeral, the bells rang in unison (nine series of 18 double strokes, each series slowly over 12 minutes). For the death of the pope, the bells rang for three days after third hour (6 double strokes, slowly over 12 minutes).[50] The bells also marked the passing of cardinals and foreign ambassadors who had died in Venice, the wife and sons of the doge, the patriarch and the canons of Saint Mark's, the procurators of Saint Mark, and the Grand Chancellor (the highest ranking civil servant).[53]

Collapse and rebuilding

Collapse

When the lean-to stalls were removed from the sides of the bell tower in 1873–1874, the base was discovered to be in poor condition. But restoration was limited to repairing surface damage. Similarly, excavations in Saint Mark's Square in 1885 raised concerns for the state of the foundation and the stability of the structure. Yet inspection reports by engineers and architects in 1892 and 1898 were reassuring that the tower was in no danger. Ensuing restoration was sporadic and primarily involved the substitution of weathered bricks.

In July 1902, work was underway to repair the roof of the loggetta. The girder supporting the roof where it rested against the tower was removed by cutting a large fissure, roughly 40 centimetres (16 in) in height and 30 centimetres (12 in) in depth, at the base of the tower. On 7 July, it was observed that the shaft of the tower trembled as workmen hammered the new girder into place. Glass tell-tales were inserted into crevices in order to monitor the shifting of the tower. Several of these were found broken the next day.[54]

By 12 July, a large crack had formed on the northern side of the tower, running almost the entire height of the brick shaft. More accurate plaster tell-tales were inserted into the crevices. Although a technical commission was immediately formed, it determined that there was no threat to the structure. Nevertheless, wooden barricades were erected to keep onlookers at a safe distance as pieces of mortar began to break off from the widening gap and fall to the square below. Access to the tower was prohibited, and only the bell signalling the beginning and end of the work day was to be rung in order to limit vibrations. The following day, Sunday, the customary band in Saint Mark's Square was cancelled for the same reason.

The next morning, Monday 14 July, the latest tell-tales were all discovered broken; the maximum crack that had developed since the preceding day was 0.75 centimetres (0.30 in). At 09:30 it was ordered that the square be evacuated. Stones began to fall at 9:47, and at 9:53 the entire bell tower collapsed. Because of its isolated position, the resulting damage was relatively limited. Apart from the loggetta, which was completely demolished, only a corner of the historical building of the Marciana Library was destroyed. The basilica itself was protected by the pietra del bando, a large porphyry column from which laws used to be read. The sole fatality was the caretaker's cat.[55] That same evening, the communal council convened in an emergency session and voted unanimously to rebuild the bell tower exactly as it was. The council also approved an initial 500,000 Lire for the reconstruction. The province of Venice followed with 200.000 Lire on 22 July. Although a few detractors of the reconstruction, including the editorialist of the Daily Express and Maurice Barrès, claimed that the square was more beautiful without the tower and that any replica would have no historical value, "dov’era e com’era" ("where it was and how it was") was the prevailing sentiment.[56]

Rebuilding

In addition to the sums appropriated by the commune and the province, a personal donation arrived from King Victor Emmanuel III and the queen mother (100,000 Lire). This was followed by contributions from other Italian communes and provinces as well as private citizens.[57] Throughout the world, fund raising began, spearheaded by international newspapers.[58] The German scaffolding specialist Georg Leib of Munich donated the scaffolding on 22 July 1902.[59]

In autumn 1902, work began on clearing the site. The fragments of the loggetta, including columns, reliefs, capitals, and the bronze statues, were carefully removed, inventoried, and transferred to the courtyard of the Doge's Palace. Bricks that could be utilized for other construction projects were salvaged, whereas the rubble of no use was transported on barges to the open Adriatic where it was dumped.[60] By spring 1903, the site had been cleared of debris, and the remaining stub of the old tower was torn down and the material removed. The oak pilings of the mediaeval foundation were inspected and found to be in good condition, requiring only moderate reinforcement.

The ceremony to mark the commencement of the actual reconstruction took place on 25 April 1903, Saint Mark's feast day, with the blessing by the patriarch of Venice Giuseppe Sarto, later Pope Pius X, and the laying of the cornerstone by Prince Vittorio Emanuele, the count of Turin, in representation of the king. For the first two years, work consisted in preparing the foundation which was extended outward by 3 metres (9.8 ft) on all sides. This was accomplished by driving in 3076 larch piles, roughly 3.8 metres (12 ft) in length and 21 centimetres (8.3 in) in diameter.[61] Eight layers of Istrian stone blocks were then placed on top to create the new foundation. This was completed in October 1905. The first of the 1,203,000 bricks used for the new tower was laid in a second ceremony on 1 April 1906. To facilitate construction, a mobile scaffold was conceived. It surrounded the tower on all sides and was raised as work progressed by extending the braces.

With respect to the original tower, structural changes were made to provide for greater stability and decrease the overall weight. The two shafts, one inside the other, were previously independent of each other. The outer shell alone bore the entire weight of the belfry and spire; the inner shaft only partially supported the series of ramps and steps. With the new design, the two shafts were tied together by means of reinforced concrete beams which also support the weight of the ramps, rebuilt in concrete rather than masonry. In addition, the stone support of the spire was replaced with reinforced concrete, and the weight was distributed on both the inner and outer shafts of the tower.[62]

The tower itself was completed on 3 October 1908. It was then 48.175 metres (158.05 ft) in height. The following year work began on the belfry and the year after on the attic. The allegorical figures of Venice as Justice on the eastern and western sides were reassembled from the fragments that had been recuperated from the ruins and were restored. The twin effigies of the winged lion of Saint Mark located on the remaining sides of the attic had already been chiselled away and irreparably damaged after the fall of the Venetian Republic at the time of the first French occupation (May 1797 – January 1798). They were completely remade.

Work began on the spire in 1911 and lasted until 5 March 1912 when the restored statue of the archangel Gabriel was hoisted to the summit. The new campanile was inaugurated on 25 April 1912, on the occasion of Saint Mark's feast day, exactly 1000 years after the foundations of the original building had allegedly been laid.[63]

New bells

| ||||

| bell | diameter | weight | note | |

| Marangona | 180 centimetres (71 in) | 3,625 kilograms (7,992 lb) | A2 | |

| Nona | 156 centimetres (61 in) | 2,556 kilograms (5,635 lb) | B2 | |

| Meza terza | 138 centimetres (54 in) | 1,807 kilograms (3,984 lb) | C3 | |

| Trottiera | 129 centimetres (51 in) | 1,366 kilograms (3,012 lb) | D3 | |

| Maleficio | 116 centimetres (46 in) | 1,011 kilograms (2,229 lb) | E3 | |

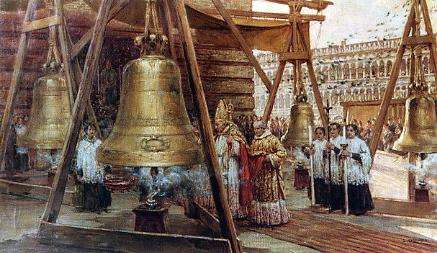

| Image: Giuseppe Cherubini, The Blessing of the Bells of Saint Mark's (1912) | ||||

Of the five bells cast by Domenico Canciani Dalla Venezia in 1820, only the largest, the Marangona, survived the collapse of the bell tower. Together with the pieces of the four shattered bells, it was transferred inside the Doge’s Palace for safekeeping during the reconstruction of the tower.

On 14 July 1908, Pope Pius X, patriarch of Venice at the time of the bell tower’s collapse in 1902, announced his intention to personally finance the recasting of the four bells as a gift to the city. The work was carried out under the supervision of the directors of the choirs of Saint Mark's and Saint Anthony's in Padua, the director of the Milan Conservatory, and the owner of the Fonderia Barigozzi of Milan.[64] The fragments of the four bells were first assembled, and moulds were made to ensure the same sizes and shapes, after which the original bronze was remelted. For the purpose, a foundry was activated near the Church of Sant'Elena, on the homonymous island, and the new Maleficio, Trottiera, Meza terza, and Nona were cast on 24 April 1909, the vigil of Saint Mark’s Feast.[note 8] After two months, the bells were tuned to harmonize with the Marangona before being transported to Saint Mark’s Square for storage.[65] They were formally blessed by Cardinal Aristide Cavallari, patriarch of Venice, on 15 June 1910 in a ceremony with Prince Luigi Amedeo in attendance, prior to being raised to the new belfry on 22 June.[66]

To ring the new bells, the earlier simple rope and lever system, used to swing the wooden headstock, was replaced with a groved wheel around which the rope is wrapped. This was done to minimize the vibrations whenever the bells are rung and hence the risk of damage to the tower.

Elevator

In 1892, it was first proposed that an elevator be installed in the bell tower. But concerns over the stability of the structure were voiced by the Regional Office for the Preservation of Veneto Monuments (Ufficio Regionale per la Conservazione dei Monumenti del Veneto). Although a special commission was nominated and concluded that the concerns were unfounded, the project was abandoned.[67]

At the time of the reconstruction, an elevator was utilized to raise the new bells to the level of the belfry, but it was only temporary. Finally, in 1962, a permanent elevator was installed. Located within the inner shaft, it employs 30 seconds to reach the belfry.[68]

Restoration work (2007–2012)

The Campanile underwent a major set of building works beginning in 2007. Like many buildings in Venice, it is built on soft ground, supported by wooden piles. Due to years of winter flooding (Acqua Alta), the subsoil has become saturated and the campanile has begun to subside and lean. Evidence of this can be seen in the increasing number of cracks in the masonry.

In order to stop the damage, a ring of titanium was built underneath the foundations of the campanile. The titanium ring will protect the campanile from the shifting soil and ensure that the tower subsides equally and does not lean.

Influence

The original Campanile inspired the designs of other towers worldwide, especially in the areas belonging to the former Republic of Venice. Almost identical, albeit smaller, replicas of the campanile exist in the Slovenian town of Piran and in the Croatian town of Rovinj; both were built in the early 17th century.

Other, later replicas include the clock tower at King Street Station in Seattle;[69] North Toronto Station; Brisbane City Hall, Australia; the Rathaus (Town Hall) in Kiel Germany; the Daniels & Fisher Tower in Denver; the Campanile in Port Elizabeth- South Africa; Sather Tower, nicknamed the Campanile, on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley;[70] 14 Wall Street; and the right-hand bell-tower of St. John Gualbert in Johnstown, Pennsylvania.

The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower, a landmark in the New York City borough of Manhattan, was designed by the architectural firm of Napoleon LeBrun & Sons, who based the external form and shape of the skyscraper on this Campanile.[71]

There is a mill chimney in Darwen, Lancashire which is modelled on the Campanile in St. Mark's Square, Venice, called India Mill.

The Custom House Tower in Boston, MA is modelled on the Campanile.

The Italianate-style tower at Jones Beach State Park, Long Island, New York, is modelled on the Campanile.[72]

The Sretenskaya church in Bogucharovo, Tula region, Russia is modelled on the Campanile.[73]

Replicas of the current tower sit on the complex of The Venetian, the Venice-themed resort on the Las Vegas Strip, its sister resort The Venetian Macao, in the Italy Pavilion at Epcot, a theme park at Walt Disney World in Lake Buena Vista, Florida, and in the nearly empty New South China Mall in Dongguan, China. Another one is in the Venice Grand Canal, Taguig in Manila, Philippines. The Venetian Towers in Barcelona, Spain, are modelled on the Campanile.

Notes

- The mediaeval chronicler, John the Deacon gives the date of construction as 897. See Agazzi, Platea Sancti Marci..., p. 19, note 12.

- The reference in the chronicle of John the Deacon to rivulus de Castello has led some historians to alternatively place the origin of the wall on the island of Olivolo. See Norwich, A History of Venice, pp. 37–38.

- The fourteenth-century map of Venice by Paolino da Venezia shows a wall only in the area of Saint Mark’s Square. But the existence of the wall at that time is not supported in contemporary documents, and the map likely reflects a previous reality. See Agazzi, Platea Sancti Marci..., pp. 14–15.

- Excavations in the early twentieth century revealed stone foundations between the bell tower and the Marciana Library which may have belonged to the early wall. See Dorigo, Venezia romanica…, I, p. 24.

- Excavations conducted in 1884 and the more detailed studies done after the collapse of the bell tower in 1902 revealed that the foundation of the bell tower consists in seven layers of varying qualities and construction techniques, an indication that the foundation was laid in different stages and over time. See Agazzi, Platea Sancti Marci..., p. 16

- Pietro Bon, consultant architect and buildings manager for the procurators of Saint Mark de supra is often confused with Bartolomeo Bon, chief consulting architect for the Salt Office. For relative documentation and the attribution of various projects, see Stefano Mariani, 'Vita e opere dei proti Bon Bartolomeo e Pietro' (unpublished doctoral thesis, Istituto Universitario di Architettura – Venezia, Dipartimento di Storia dell'Architettura, 1983)

- The legend of Venice's birth on 21 March 421 is traceable to at least the thirteenth-century chronicler Martino da Canal, Les estoires de Venise. It appears in the writings of Jacopo Dondi (Liber partium consilii magnifice comunitatis Padue, fourteenth century), Andrea Dandolo, Bernardo Giustiniani, Marin Sanudo, Marc'Antonio Sabellico, and Francesco Sansovino. See Muir, Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice, pp. 70–71.

- Some modern lists give the sequence as Maleficio, Meza-terza, Trottiera, Nona, and Marangona. But the historical texts clearly indicate that the Meza-terza was larger than the Trottiera.

References

- Fasoli, Le incursioni ungare..., pp. 96–100

- Kristó, Hungarian History in the Ninth Century, p. 198

- Parrot, The Genius of Venice, p. 30

- Agazzi, Platea Sancti Marci..., p. 16

- Dorigo, Venezia romanica…, I, p. 24

- Agazzi, Platea Sancti Marci..., p. 16

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 3

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, pp. 4–5

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 7

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 8

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 10

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, pp. 9–11

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 13

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 9–17

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 18–20

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, pp. 21–22

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, pp. 23–25

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, pp. 32–34

- Rosand, Myths of Venice…, p. 25

- Rosand, Myths of Venice…, pp. 32–36

- Sanudo, Diari, XVI (1886), 6 July 1513

- Distefano, Centenario del Campanile di san Marco..., p. 25

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, pp. 73–74

- Vitruvius, De architectura (1.6.4)

- Sansovino, Venetia città nobilissima et singolare..., fol. 106r

- Rosand, Myths of Venice…, pp. 12–16

- Rosand, Myths of Venice…, pp. 16–18

- Distefano, Centenario del Campanile di san Marco..., pp. 26–27

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, pp. 37–38

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 44

- Distefano, Centenario del Campanile di san Marco..., p. 27

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 38

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 39

- Distefano, Centenario del Campanile di san Marco..., pp. 30–31

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 42

- Block, Benjamin Franklin..., p. 91

- Distefano, Centenario del Campanile di san Marco..., pp. 31–32

- Whitehouse, Renaissance Genius..., p. 77

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 50

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, pp. 51–54

- Doglioni, Historia Venetiana, p. 87

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 135

- Sansovino and Stringa, Venetia città nobilissima et singolare…, 1604 edn, fol. 202v

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, pp. 61–64

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 128

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, pp. 51–54

- Sansovino, Le cose maravigliose et notabili della citta' di Venetia…, p. 160

- Sansovino, Le cose maravigliose et notabili della citta' di Venetia…, p. 159

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, pp. 54–55

- Sansovino, Le cose maravigliose et notabili della citta' di Venetia…, p. 161

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, pp. 55 and 57–58

- Sansovino, Le cose maravigliose et notabili della citta' di Venetia…, pp. 160–161

- Sansovino, Le cose maravigliose et notabili della citta' di Venetia…, pp. 161–162

- Distefano, Centenario del Campanile di san Marco..., pp. 39–41

- Distefano, Centenario del Campanile di san Marco..., p. 45

- Distefano, Centenario del Campanile di san Marco..., pp. 50–52

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, pp. 117–118

- Distefano, Centenario del Campanile di san Marco..., p. 50

- "Stadtchronik 1902: Bemerkenswertes, Kurioses und Alltägliches" (in German), muenchen.de.

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, pp. 121–123

- Marchesini, Un secolo all'ombra..., p. 100

- Marchesini, Un secolo all'ombra..., pp. 94–95

- Fenlon, Piazza San Marco, p. 147

- Marchesini, Un secolo all'ombra..., p. 110

- Marchesini, Un secolo all'ombra..., p. 120

- Gattinoni, Storia del Campanile…, p. 134

- Distefano, Centenario del Campanile di san Marco..., p. 36

- Distefano, Centenario del Campanile di san Marco..., pp. 67 and 70–71

- Margaret A. Corley (March 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form" (PDF). National Park Service, Department of Interior. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- Finacom, Steven. "Berkeley Landmarks: Sather Tower (Campanile)". Retrieved 5 March 2008.

- "Before This Seven-Day Wonder in Construction Is Completed It Will Be Overtopped by the Tall Tower of the Metropolitan Life". The New York Times. December 29, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- Bleyer, Bill (5 October 2010). "Copper roof installed on Jones Beach water tower (partly subscriber access)". Newsday. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- arch_heritage (2008-01-31). "АТАКА КЛОНОВ: колокольня в усадьбе Богучарово". АРХИТЕКТУРНОЕ НАСЛЕДИЕ. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

Bibliography

- Agazzi, Michela, Platea Sancti Marci: I luoghi marciani dall'XI al XIII secolo e la formazione della piazza (Venezia: Comune di Venezia, Assessorato agli affari istituzionali, Assessorato alla cultura and Università degli studi, Dipartimento di storia e critica delle arti, 1991)

- Block, Seymour Stanton Benjamin Franklin, Genius of Kites, Flights and Voting Rights (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2004) ISBN 9780786419425

- Distefano, Giovanni, Centenario del Campanile di san Marco 1912–2012 (Venezia: Supernova, 2012)

- Doglioni, Giovanni Nicolò, Historia Venetiana scritta brevemente da Gio. Nicolo Doglioni, delle cose successe dalla prima fondation di Venetia sino all'anno di Christo 1597 (Venetia: Damian Zenaro, 1598)

- Dorigo, Wladimiro, Venezia romanica: la formazione della città medioevale fino all'età gotica, 2 vols (Venezia: Istituto veneto di scienze, lettere ed arti, 2003)

- Fasoli, Gina, Le incursioni ungare in Europa nel secolo X (Firenze: Sansoni, 1945)

- Fenlon, Iain, Piazza San Marco (London: Profile Books, 2010)

- Festa, Egidio, Galileo: la lotta per la scienza (Roma: GLF editori Laterza, 2007)

- Gattinoni, Gregorio, Il campanile di San Marco in Venezia (Venezia: Tip. libreria emiliana, 1912)

- Kristó, Gyula, Hungarian History in the Ninth Century (Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Muhely, 1996)

- Marchesini, Maurizia, Un secolo all'ombra, crollo e ricostruzione del Campanile di San Marco (Belluno: Momenti Aics, 2002)

- Muir, Edward, Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981) ISBN 0691102007

- Norwich, John Julius, A History of Venice (New York: Vintage Books, 1982)

- Parrot, Dial, The Genius of Venice: Piazza San Marco and the Making of the Republic (New York: Rizzoli, 2013)

- Rosand, David, Myths of Venice: the Figuration of a State (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001) ISBN 0807826413

- Sansovino, Francesco, Le cose maravigliose et notabili della citta' di Venetia. Riformate, accomodate, & grandemente ampliate da Leonico Goldioni (Venetia, Domenico Imberti, 1612)

- Sansovino, Francesco, Venetia città nobilissima et singolare descritta in 14 libri (Venetia: Iacomo Sansovino, 1581)

- Sansovino, Francesco and Giovanni Stringa, Venetia città nobilissima et singolare… (Venetia: Altobello Salicato,1604)

- Sanudo, Marin, Diari, ed. by G. Berchet, N. Barozzi, and M. Allegri, 58 vols (Venezia: [n. pub.], 1879–1903)

- Torres, Duilio, Il campanile di San Marco nuovamente in pericolo?: squarcio di storia vissuta di Venezia degli ultimi cinquant'anni (Venezia: Lombroso, 1953)

- Whitehouse, David, Renaissance Genius: Galileo Galilei & His Legacy to Modern Science (New York: Sterling Publishing, 2009)

- Zanetto, Marco, Il cambio d'abito del "Paron de casa": da torre medievale a campanile rinascimentale (Venezia: Società Duri i banchi, 2012)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Campanile of St. Mark's Basilica. |