Squirm

Squirm is a 1976 American natural horror film that was written and directed by Jeff Lieberman, and stars Don Scardino, Patricia Pearcy, R.A. Dow, Jean Sullivan, Peter MacLean, Fran Higgins, and William Newman. The film takes place in the fictional town of Fly Creek, Georgia, which becomes infested with carnivorous worms after a storm directs electricity from power lines onto wet soil. Lieberman was inspired to write the script by a childhood incident in which electricity was fed into a patch of earth, causing earthworms to emerge at the surface.

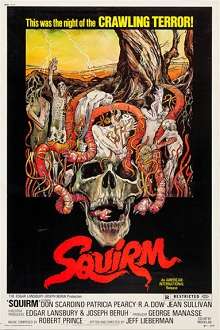

| Squirm | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jeff Lieberman |

| Produced by | George Manasse |

| Written by | Jeff Lieberman |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Robert Prince |

| Cinematography | Joseph Mangine |

| Edited by | Brian Smedley-Aston |

Production company | The Squirm Company[1] |

| Distributed by | American International Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 93 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Most of the film's budget came from Broadway producers Edgar Lansbury and Joseph Beruh. The film was shot in Port Wentworth, Georgia, in the course of five weeks, during which millions of worms from Georgia and Maine were used. Makeup artist Rick Baker provided special effects for the film using prosthetics for the first time in his career. Squirm was picked up for distribution by American International Pictures and was edited from an "R" rating to a "PG" rating. The film received lukewarm reviews from critics but was financially successful. It later garnered positive reception in retrospective evaluations. Squirm was featured as a tenth-season episode of the comedy television series Mystery Science Theater 3000 in 1999.

Plot

On the evening of September 29, 1975, in the rural town of Fly Creek, Georgia, a powerful storm blows down an overhead power line, leaving the town without electricity. The power line lands on wet soil and starts to electrocute the worms underneath. The next morning, Geraldine "Geri" Sanders' boyfriend Mick is due to arrive from New York City for a vacation; she uses a truck belonging to her neighbor, worm farmer Roger Grimes, to pick up Mick. While Geri and Mick go to town, Roger's shipment of 100,000 bloodworms and sandworms escape. Mick enters a diner, where a customer says over 300,000 volts are being released into the ground from severed power lines. Mick orders an egg cream and finds a worm in it, though the owner and Sheriff Jim Reston believe he is joking.

Geri introduces Mick to her mother Naomi and sister Alma, before they both leave to browse at antique dealer Aaron Beardsley's house. Outside, Roger's father Willie finds the shipment of worms is missing. Roger sees Mick with Geri and becomes envious of their relationship. Geri and Mick arrive at Beardsley's house; they do not find him but Geri sees a human skeleton outside the property. They bring over Sheriff Reston but the skeleton disappears. Thinking it is another prank, Reston threatens to arrest Mick if he returns to the town. When they ask locals about Beardsley's whereabouts, they find out he was last seen before the storm. Mick believes he himself unintentionally released the worms; he apologizes to Roger and invites him to go fishing with him and Geri. They find the skeleton in Roger's truck.

While on the boat, Mick is bitten by a worm. Roger tells him worms attack when electrified. Mick leaves Geri with Roger so he can tend to his wound; he and Alma take the skeleton's skull to an abandoned dental office, where they compare its teeth with X-rays and confirm the skeleton is Beardsley's. Roger makes advances towards Geri but the worms they brought as bait attack him and crawl into his face. He runs off into the woods and Geri tells Mick. Mick and Geri visit the worm farm to find Roger but Mick finds Willie's body being eaten by worms. They try telling Sheriff Reston but he ignores them. Mick deduces the worms killed Beardsley but cannot figure out the reason.

While Mick and Geri are eating dinner with Naomi and Alma, the worms eat through the roots of a tree, causing it to crash into the house. Mick realizes electricity is still being released from the power lines and that the wet soil is acting as a conductor; he also remembers the worms only come out at night. Mick tells Geri to keep everyone inside equipped with candles and leaves to get plywood to board up the house. Roger, whose face has been deformed by worms, attacks Mick and knocks him unconscious. Roger enters the house and kidnaps Geri. The worms infest the house, and also attack other places in town. Sheriff Reston and a woman are eaten alive in a jail cell, and people at a bar are also attacked and eaten.

Mick regains consciousness and finds Naomi's remains, covered in worms, at the house. When he goes upstairs, Roger attacks and chases him downstairs. Mick pushes Roger into a pile of worms, which engulf him. Mick frees Geri and tells her Naomi, and presumably Alma, are dead. The two try to escape but Roger bites Mick in the leg while they climb out of a window. Mick beats Roger to death before climbing into a tree, where he and Geri stay until morning. The worms disappear and they both wake up to find a repairman telling them the power has been restored. Alma survived by hiding in a chest, and Geri and Mick rush into the house to meet her.

Cast

- Don Scardino as Mick

- Patricia Pearcy as Geraldine "Geri" Sanders

- R.A. Dow as Roger Grimes

- Jean Sullivan as Naomi Sanders

- Peter MacLean as Sheriff Jim Reston

- Fran Higgins as Alma Sanders

- William Newman as Quigley

- Barbara Quinn as the sheriff's girl

- Carl Dagenhart as Willie Grimes

- Angel Sande as Millie

- Carol Jean Owens as Lizzie

- Kim Leon Iocovozzi as Hank

- Walter Dimmick as Danny

- Leslie Thorsen as Bonnie

- Julia Klopp as Mrs. Klopp

Production

.jpg)

Squirm was written by Jeff Lieberman, who at the time was also working for Janus Films on a series called The Art of Film. Lieberman said the script was inspired by an incident in which his brother connected a transformer to the ground, causing worms to emerge. He completed the rough draft in six weeks then gave it to producer George Manasse, who saw potential in it. Manasse showed Lieberman's script to then-independent Broadway producers Edgar Lansbury and Joseph Beruh, who bought Squirm in 1975 and invested $470,000 into the project. The original filming location and setting was New England[2] but this was changed to Port Wentworth, Georgia,[3] due to unsuitable fall weather conditions in New England.[2]

Production began in November 1975. Half of the worms used in the film were made of rubber, the other half included large sandworms from Maine that were taken from the ground by using a wire connected to a rheostat. They were then refrigerated and transported to Port Wentworth.[2] The University of Georgia Oceanographic Institute at Skidaway Island, Georgia, also provided an estimated three million Glycera worms.[1] One scene in which a living room is filled with worms was accomplished by building a scaffolding four feet (1.2 m) above the ground; a canvas was placed on top and covered with thousands of worms that were six inches deep. The local Boy Scouts troop were hired to assist in handling the worms; they received merit badges for their work.[4] After production wrapped, newspapers in Maine reported the local fishing industry had been ruined by a shortage of worms caused by the film production.[2]

Brian Smedley-Aston edited Squirm.[5] Robert Prince was the composer for the film; he conducted a full-orchestra soundtrack in England. Bernard Hermann, composer for The Day the Earth Stood Still and Psycho, was originally slated to write the score but died before beginning work.[6] Joe Mangine was the director of photography while Henry Shrady was the art director.[4] Special make-up effects artist Rick Baker created the make-up in New York for Richard A. Dow's character Roger, who turns into "Wormface", and made a facial mold using prosthetics, which were new to him.[2]

Principal photography wrapped after five weeks, seven days of which were dedicated to working with the worms. Lieberman was heavily involved with the post-production work, which included making the sound effects for the worms using balloons and shears, and looping the two sounds using multitrack recording. The worms' screams were taken from a scene in which pigs are slaughtered in Brian De Palma's 1976 film Carrie.[2]

Release

Squirm was shown during the 1976 Cannes Film Festival. It was later acquired by American International Pictures (AIP), who released it theatrically in the United States on July 14, 1976, and worldwide on August 9th that year.[1][7] AIP had given a $250,000 advance to the film's producers for domestic distribution and $500,000 in guarantees from sixteen territories.[1] When the film was first submitted to the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), AIP intended the film to get a "PG" rating. The MPAA instead gave the film an "R" rating, citing some scenes that were deemed "objectionable to PG-rated sensibilities".[2] AIP later made edits to the film in an attempt to get a "PG" rating, cutting the running time to 92 minutes.[2][8] The re-edited film would later be shown as the television version. Despite the edits, the film was financially successful; producers Edgar Lansbury and Joseph Beruh made their investment back from the foreign theatrical market.[2]

The film was released on VHS by Vestron Video in 1983.[9] It was later released on DVD by MGM Home Entertainment in 2003. The DVD version, with a 93 minute run time, restored a shower scene with Patricia Pearcy and includes an audio commentary with Jeff Lieberman as part of the special features.[10] MGM later released in 2011 as part of a set with Swamp Thing and The Return of the Living Dead.[11] The unedited R-rated version was released in the United Kingdom on Blu-ray and DVD by Arrow Video on September 23, 2013.[12] This version was also released in the United States on Blu-ray by Shout! Factory under its label Scream Factory on October 28, 2014.[13]

Reception

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, Squirm has an approval rating of 36% based on 14 reviews with an average rating of 4.6 out of 10.[14]

Contemporary reviews were lukewarm upon its release. Reviews of the special effects were mixed,[8][15] with Variety describing them as genuinely creepy. However, the reviewer believed their effect was offset by the "clumsy and amateurish" production.[15] Vincent Canby of The New York Times, while finding the scenes with the worms "effectively revolting", negatively compared the shot of Roger sinking into a pile of worms to spaghetti with meat sauce. Canby also gave mild praise for the acting, saying that Scardino and Pearcy gave decent performances.[8] Critics were divided on Jeff Liberman's direction.[16][17][18] Cinefantastique contributor Kyle B. Counts criticized the way the film cut away from violent moments to scenes of comic relief, opining that it undermined the film's "threadbare" tension.[16] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times was more positive, as he thought the film had a good balance of its use of humor and terror, and praised Lieberman for displaying "plenty of panache" and "deftly playing a disarming folksy atmosphere against rapidly escalating peril".[17] John Pym of The Monthly Film Bulletin also praised the use of humor and narrative in the film, believing Squirm to be commendable and a scary addition to the genre.[18]

Squirm received generally positive evaluations in retrospective reviews. Praise was given to its cinematography,[19][20] special effects,[21][22] and its horror elements.[19][23] Donald Guarisco for AllMovie saying that Squirm is an "excellent example of the 'revenge of nature' horror" genre.[19] Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide gave a similar sentiment, describing it as an "above-average horror outing [that] builds to good shock sequences".[23] In his book American International Pictures: A Comprehensive Filmography, Rob Craig considered it to be "an entertaining – and fairly insightful − film which is certainly not uncritical to its main characters and their community".[21] Other critics were less positive towards the film. John Kenneth Muir while commending the cinematography and imagery, stated the film's inconsistent tone and lack of believable characters undermines the whole experience, overall calling it "a letdown".[24] Jim Craddock, author of VideoHound's Golden Movie Retriever, summarized it as an "okay" giant worm movie.[20] TV Guide meanwhile thought it was an underrated effort like Lieberman's other works.[22] In 2010, Kate Abbott for Time listed Squirm as one of the best "Killer-Animal Movies".[25]

Analysis

Squirm can be seen as part of a tradition of 1970s "revenge of nature" films, the most important of which is Jaws.[26][27] This genre began in the early 1970s with films like Frogs, Night of the Lepus, and Sssssss, leading on to Jaws, Squirm, Empire of the Ants, and Kingdom of the Spiders.[26] It can also be seen, along with other "nature-running-amok thrillers" of the latter half of the 1970s including The Food of the Gods, The Pack, The Car, The Swarm, Empire of the Ants, Long Weekend, and Day of the Animals, as a "Jawsploitation" film that exploits the success of Jaws.[28] The film studies scholar I.Q. Hunter disputes this, arguing Jaws merely served to perpetuate the early-1970s genre Quentin Tarantino called the "Mother Nature goes ape-shit kind of movie".[28] Muir calls Squirm one of the "eco-horrors" of the 1970s, along with Frogs, Night of the Lepus, Day of the Animals, Kingdom of the Spiders, Empire of the Ants, The Swarm, and Prophecy. These films reflect attitudes and fears prevalent at the time, reflecting the public's unease about what Muir called "man's continued pillaging and pollution of the Earth".[29]

Robin Wood used Squirm as an example of nature films linking "natural" forces to sexual and familiar tensions. Wood also expressed disappointment with the film's ending because he felt the survival of Mick, Geri, and Alma counteracts the film's logic. He interpreted the film's world as "totally overwhelmed by eruptions of devouring worms that develop, initially, out of familiar constraints and sexual possessiveness".[30] Rob Craig said the worms in the film can be seen as a metaphor for "a country bumpkin's slimy, limp penis: a laughably vulnerable object by itself, but fearsomely dangerous in aggregate". Craig added that the film has an "anti-breeding" angle in its subtext, framing rural males as nothing more than a "worm farm", which would be dangerous as a societal force.[21] Kyle B. Counts notes similarities between the themes of "masculine ideals" in Squirm and Straw Dogs, in both of which the male leads are the hero. The reviewer also said the film does not give the impression Don Scardino's character grew into a "man" after his experience.[16]

In 2014, Liberman wrote a foreword for the book Subversive Horror Cinema: Countercultural Messages of Films from Frankenstein to the Present by Jon Towlson. In this, he addressed the critical and scholarly analysis of Squirm:

In my first movie, Squirm (1976), I really didn't try to make any sort of social or political comment. At least not consciously. However, soon after the movie's release, critics found some very profound subtexts which I myself wasn't aware of. Nature getting revenge on man for his disrespect of ecology. The symbolism of man's mortality and his inevitable fate of becoming worm food. Even themes of suppressed sexuality in the main characters. This could all very well be true, but if it is, it was not done purposely on my part.

— Jeff Lieberman, Subversive Horror Cinema: Countercultural Messages of Films from Frankenstein to the Present [31]

Legacy

Director Brian De Palma included a poster of Squirm in several scenes of his 1981 film Blow Out. Jeff Lieberman, who idolized De Palma, told Fangoria he met De Palma years later and asked him about the poster. De Palma reportedly answered "Only use the best!"[2] Pittsburgh musician Weird Paul Petroskey created an album titled Worm in My Egg Cream, which he dedicated to the "worm in the egg cream" scene and made extensive use of samples from the film. All 16 tracks on the album are titled "Worm in My Egg Cream".[32]

Squirm was featured in a tenth-season episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000 (MST3K), a comedy television series in which the character Mike Nelson and his two robot friends Crow T. Robot and Tom Servo are forced to watch bad films as part of an ongoing scientific experiment. The episode was broadcast on the Sci-Fi Channel on August 1, 1999, and was the penultimate episode to the series.[33][34] It was shown along with the short film A Case of Spring Fever.[34] In response to the episode, Jeff Lieberman, while not caring about MST3K making fun of his film, voiced his frustration towards it being sold to the show, saying it cheapened the value of the movie.[35] In 2014, Shout! Factory released the MST3K episode as part of the "Turkey Day Collection", along with episodes focused on Jungle Goddess, The Painted Hills, and The Screaming Skull.[34]

References

Citations

- "Squirm". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- Szulkin, David (June 1993). "The Squirm Turns". Fangoria. No. 123. pp. 24–29.

- Muir 2012, p. 18.

- Staff Writer (January 12, 1976). "Horror-Thriller 'Squirm' Completed in Georgia". Box Office. p. 16.

- Lynn, France (October 1992). "Expose". Shivers. No. 3. pp. 19–21.

- O'Quinn, Kerry (August 1976). "Squirm". Starlog. No. 1. pp. 20–21.

- Staff Writer (July 19, 1976). "AIP Arranges July Release of Terror Drama 'Squirm'". Box Office. p. 5.

- Canby, Vincent (July 31, 1976). "The Screen:'Squirm' Shows Worms Turning on People". The New York Times: 8. Archived from the original on August 6, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- Dr. Cyclops (September 1983). "The Video Eye of Dr. Cyclops". Fangoria. No. 29. p. 27.

- Gross, G. Noel (August 26, 2003). "Squirm: SE". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- "Squirm – Releases". Allmovie. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- "Jeff Lieberman's cult classic Squirm hitting UK Blu-Ray & DVD September 23". JoBlo.com. September 4, 2013. Archived from the original on September 8, 2013. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- Miska, Brad (August 26, 2014). "Scream Factory! Will Make You 'Squirm' This Halloween". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

- "Squirm (1976) – Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- "Squirm". Variety: 19. August 11, 1976.

- Counts, Kyle (Winter 1976). "Film Ratings". Cinefantastique. Vol. 5 no. 3. p. 29.

- Thomas, Kevin (December 17, 1976). "As the Worm Turns: 'Squirm'". Los Angeles Times. p. 21.

- Pym, John (September 1976). "Squirm". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 43 (512): 199.

- Guarisco, Donald. "Squirm (1976)". Allmovie. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- Craddock 2006, p. 809.

- Craig 2019, p. 349.

- "Squirm Review". TV Guide. Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- Maltin 2013, p. 1318.

- Muir 2012, pp. 134–136.

- Abbott, Kate (August 19, 2010). "Top 10 Killer-Animal Movies". Time: 6. Archived from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- Verevis 2016, p. 102.

- Platts 2015, pp. 156–7.

- Hunter 2016, p. 85.

- Muir 2012, p. 2.

- Wood 2018.

- Towlson 2014, p. 1.

- "The Music of Weird Paul". www.weirdpaul.com. Archived from the original on July 20, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- "Mystery Science Theater 3000 Season 10 Episode Guide". TV Guide. Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- Sinnott, John (November 25, 2014). "Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Turkey Day Collection". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- Faraci, Devin (August 14, 2013). "Why The Director Of Squirm Was Furious About The MST3K Version Of His Movie". Birth.Movies.Death. Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

Bibliography

- Craddock, Jim (2006). VideoHound's Golden Movie Retriever. Gale Group. ISBN 0-7876-8980-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Craig, Rob (2019). American International Pictures: A Comprehensive Filmography. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-6631-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- I.Q. Hunter (8 September 2016). Cult Film as a Guide to Life: Fandom, Adaptation, and Identity. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62356-381-3.

- Maltin, Leonard; Carson, Darwyn (2013). Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide: The Modern Era. Signet. ISBN 978-0-451-41810-4.

- Muir, John (November 22, 2012). Horror Films of the 1970s. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9156-8.

- Platts, Todd K. (2015). "The New Horror Movie". In Cogan, Brian; Gencarelli, Thom (eds.). Baby Boomers and Popular Culture. Praeger. pp. 147–64.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Towlson, Jon (2014). Subversive Horror Cinema: Countercultural Messages of Films from Frankenstein to the Present. McFarland. ISBN 978-147-6-6153-32.

- Verevis, Constantine (March 15, 2016). "Vicious cycle: Jaws and the revenge-of-nature films of the 1970s". In Amanda Ann Klein; R. Barton Palmer (eds.). Cycles, Sequels, Spin-offs, Remakes, and Reboots: Multiplicities in Film and Television. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-4773-0817-2.

- Wood, Robin (2018). "Return of the Repressed". Robin Wood on the Horror Film: Collected Essays and Reviews. Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8143-4524-5.

External links

- Squirm at AllMovie

- Squirm at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Squirm on IMDb

- Squirm at the TCM Movie Database