Slalom skiing

Slalom is an alpine skiing and alpine snowboarding discipline, involving skiing between poles or gates. These are spaced more closely than those in giant slalom, super giant slalom and downhill, necessitating quicker and shorter turns. Internationally, the sport is contested at the FIS Alpine World Ski Championships, and at the Olympic Winter Games.

The term may also refer to waterskiing on one ski.

History

The term slalom comes from the Morgedal/Seljord (a Norwegian dialect) word "slalåm": "sla", meaning slightly inclining hillside, and "låm", meaning track after skis.[1] The inventors of modern skiing classified their trails according to their difficulty. Slalåm was a trail used in Telemark by boys and girls not yet able to try themselves on the more challenging runs. Ufsilåm was a trail with one obstacle (ufse) like a jump, a fence, a difficult turn, a gorge, a cliff (often more than 10 metres (33 ft) high) and more. Uvyrdslåm was a trail with several obstacles.[2] A Norwegian military downhill competition in 1767 included racing downhill among trees "without falling or breaking skis". Sondre Norheim and other skiers from Telemark practiced uvyrdslåm or "disrespectful/reckless downhill" where they raced downhill in difficult and untested terrain (i.e., off piste). The 1866 "ski race" in Oslo was a combined cross-country, jumping and slalom competition. In the slalom participants were allowed use poles for braking and steering, and they were given points for style (appropriate skier posture). During the late 1800s Norwegian skiers participated in all branches (jumping, slalom, and cross-country) often with the same pair of skis. Slalom and variants of slalom were often referred to as hill races. Around 1900 hill races are abandoned in the Oslo championships at Huseby and Holmenkollen. Mathias Zdarsky's development of the Lilienfeld binding helped change hill races into a specialty of the Alps region.[3]

The rules for the modern slalom were developed by Arnold Lunn in 1922 for the British National Ski Championships, and adopted for alpine skiing at the 1936 Winter Olympics. Under these rules gates were marked by pairs of flags rather than single ones, were arranged so that the racers had to use a variety of turn lengths to negotiate them, and scoring was on the basis of time alone, rather than on both time and style.[4][5]

Course

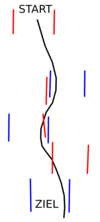

A course is constructed by laying out a series of gates, formed by alternating pairs of red and blue poles. The skier must pass between the two poles forming the gate, with the tips of both skis and the skier's feet passing between the poles. A course has 55 to 75 gates for men and 40 to 60 for women. The vertical drop for a men's course is 180 to 220 m (591 to 722 ft) and slightly less for women.[6] The gates are arranged in a variety of configurations to challenge the competitor.

Because the offsets are relatively small in slalom, ski racers take a fairly direct line and often knock the poles out of the way as they pass, which is known as blocking. (The main blocking technique in modern slalom is cross-blocking, in which the skier takes such a tight line and angulates so strongly that he or she is able to block the gate with the outside hand.) Racers employ a variety of protective equipment, including shin pads, hand guards, helmets and face guards.

Clearing the gates

Traditionally, bamboo poles were used for gates, the rigidity of which forced skiers to maneuver their entire body around each gate.[7] In the early 1980s, rigid poles were replaced by hard plastic poles, hinged at the base. The hinged gates require, according to FIS rules, only that the skis and boots of the skier go around each gate.

The new gates allow a more direct path down a slalom course through the process of cross-blocking or shinning the gates.[8] Cross-blocking is a technique in which the legs go around the gate with the upper body inclined toward, or even across, the gate; in this case the racer's outside pole and shinguards hit the gate, knocking it down and out of the way. Cross-blocking is done by pushing the gate down with the arms, hands, or shins.[9] By 1989, most of the top technical skiers in the world had adopted the cross-block technique.[10]

Equipment

With the innovation of shaped skis around the turn of the 21st century, equipment used for slalom in international competition changed drastically. World Cup skiers commonly skied on slalom skis at a length of 203–207 centimetres (79.9–81.5 in) in the 1980s and 1990s but by the 2002 Olympic Winter Games in Salt Lake City, the majority of competitors were using skis measuring 160 cm (63.0 in) or less.

The downside of the shorter skis was that athletes found that recoveries were more difficult with a smaller platform underfoot. Out of concern for the safety of athletes, the FIS began to set minimum ski lengths for international slalom competition. The minimum was initially set at 155 cm (61.0 in) for men and 150 cm (59.1 in) for women, but was increased to 165 cm (65.0 in) for men and 155 cm (61.0 in) for women for the 2003–2004 season.

The equipment minimums and maximums imposed by the International Ski Federation (FIS) have created a backlash from skiers, suppliers, and fans. The main objection is that the federation is regressing the equipment, and hence the sport, by two decades. [11]

American Bode Miller hastened the shift to the shorter, more radical sidecut skis when he achieved unexpected success after becoming the first Junior Olympic athlete to adopt the equipment in giant slalom and super-G in 1996. A few years later, the technology was adapted to slalom skis as well.

Men's Slalom World Cup podiums

In the following table men's slalom World Cup podiums in the World Cup since first season in 1967.[12]

References

- Kunnskapsforlagets idrettsleksikon. Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget, 1990, p.273.

- NAHA // Norwegian-American Studies

- Bergsland, E.: På ski. Oslo: Aschehoug, 1946, p.27.

- Hussey, Elisabeth. "The Man Who Changed the Face of Alpine Skiing", Skiing Heritage, December 2005, p. 9.

- Bergsland, Einar (1952). Skiing: a way of life in Norway. Oslo: Aschehoug.

- Slade, Daryl (February 12, 1988). "Alpine evolution continues". Ocala (FL) Star-Banner. Universal Press Syndicate. p. 4E.

- "Alpine skiing: Stenmark on slalom". Observer-Reporter. Washington, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. February 13, 1994. p. C7.

- McMillan, Ian (February 28, 1984). "A new line in slalom poles". Glasgow Herald. p. 24.

- Bell, Martin. "A matter of course". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Gurshman, Greg. "To Cross-Block or Not To Cross-Block?". Archived from the original on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- "Giant Slalom Racers Object to a Mandate on New Equipment". The New York Times. 22 November 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- "Winter Sports Chart - Alpine Skiing". wintersport-charts.info. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

External links