Skull roof

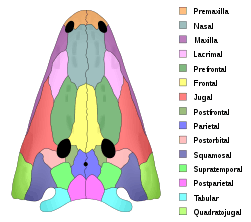

The skull roof, or the roofing bones of the skull, are a set of bones covering the brain, eyes and nostrils in bony fishes and all land-living vertebrates. The bones are derived from dermal bone and are part of the dermatocranium.

In comparative anatomy the term is used on the full dermatocranium.[1] In general anatomy, the roofing bones may refer specifically to the bones that form above and alongside the brain and neurocranium (i.e., excluding the marginal upper jaw bones such as the maxilla and premaxilla),[2] and in human anatomy, the skull roof often refers specifically to the skullcap.

Origin

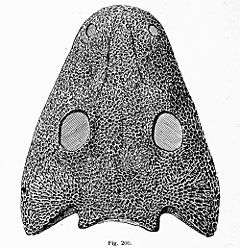

Early armoured fish did not have a skull in the common understanding of the word, but had an endocranium that was partially open above, topped by dermal bones forming armour. The dermal bones gradually evolved into a fixed unit overlaying the endocranium like a heavy "lid", protecting the animal's head and brain from above. Cartilaginous fish whose skeleton is formed from cartilage lack a continuous dermal armour and thus have no proper skull roof. A more or less full shield of fused dermal bones was common in early bony fishes of the Devonian, and particularly well developed in shallow water species.[3]

Bony fishes and amphibians

In early sarcopterygians the skull roof was composed of numerous bony plates, particularly around the nostrils and behind each eye. The skull proper was joined by the bones of the operculum. The skull itself was composed rather loosely, with a joint between the bones covering the brain (the parietal bones and the bones behind them) and the snout (the frontal bone, nasal bone and the bones in front and to the side of them). This joint disappeared in the evolving labyrinthodonts, at the same time the number of bones were reduced and the operculum disappeared.[1]

In frogs and salamanders the skull roof is further reduced and has large openings. Only in caecilians can a full covering skull roof be found, an adaption for burrowing.[4]

The skull roof in lungfish is composed of a number of bony plates that are not readily compared to those found in early amphibians.[5] In most ray-finned fishes the skull is often reduced to a series of loose elements, and a skull roof as such is not found.[3]

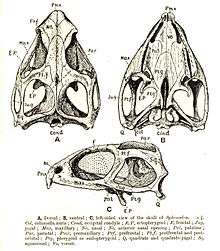

Labyrinthodonts and early reptiles

The pattern of plates of the labyrinthodonts formed that basis for that seen in all land-living vertebrates. The roof itself formed a continuous cover over the whole of the head, leaving only openings for nostrils, eyes and a parietal eye between the parietal bones. This type of skull was inherited by the first reptiles as they evolved from labyrinthodont stock in the Carboniferous. This type of skull roof without any above openings behind the eyes is called anapsid. Today anapsid skulls are only found in turtles, though this may be a case of secondary loss of the post orbital openings.[6]

Diapsids and synapsids

In two groups of early reptiles the skull roof evolved post orbital openings to allow for greater movement of the jaw muscles. The two groups evolved the openings independently:

- The Synapsids having one opening on each side, fairly low on the side of the skull, between the zygomatic bone and the elements above.

- The Diapsids having two openings on each side, the two openings separated by an arch formed from processes of the postorbital and squamosal bones.

The synapsids are the mammal-like reptiles and the mammals. In mammals, the side opening is closed by the sphenoid bone, so that the skull roof appear whole, despite the temporal opening. All other reptiles (with the possible exception of turtles) and the birds are diapsids.

References

- Romer, A.S. & T.S. Parsons. 1977. The Vertebrate Body. 5th ed. Saunders, Philadelphia. (6th ed. 1985)

- Kent, George C.; Carr, Robert K. (2001). Comparative Anatomy of the Vertebrates (9th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-303869-5.

- Miller, George C. Kent, Larry (1997). Comparative anatomy of the vertebrates (8th ed.). Dubuque, IA: Wm. C. Brown. ISBN 0697243788.

- Trueb, William E. Duellman, Linda Trueb; illustrated by Linda (1994). Biology of amphibians (Johns Hopkins pbk. ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-4780-X.

- Carroll, R.L. (1988): Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, W.H. Freeman & Co, New York NY, p.148

- deBraga, M. and Rieppel, O. (1997). "Reptile phylogeny and the interrelationships of turtles." Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 120: 281-354.