Silk Road transmission of art

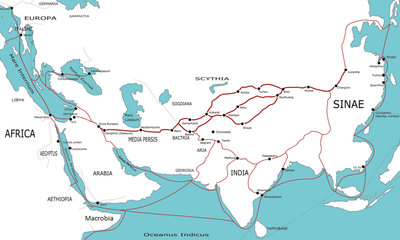

Many artistic influences transited along the Silk Road, especially through the Central Asia, where Hellenistic, Iranian, Indian and Chinese influence were able to interact. In particular Greco-Buddhist art represent one of the most vivid examples of this interaction. As shown on the 1st century CE Silk Road map, there is no single road but a whole network of long-distance routes: mainly two land routes and one sea route. The Silk Road served as an outlet to connect cultures with goods, ideas, religions, artistic influences and more. These routes fostered shared cultures, transcended existing borders and laid the foundation for collaborative cultural development politically, economically, and socially. The Silk Road acted as the world’s first superhighway linking China and Japan to Europe across Central Asia from ancient times via caravans and bazaars. This allowed for artforms to have a blend of different cultures from areas separated by bodies of water or large land masses. The common theme among different regions of the Silk Road is that art lives in ritual acts. The ritualistic component is rooted in tradition and helped religions survive.

Where it Began

Southern Asia is the oldest part of Asia and was the Birthplace of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. All of the major ancient civilizations of the world were located near rivers or the sea. The Indus Valley Civilization of Harappa is noted to have had a granary and public well around 2500-2000 BCE. This reflects the long term nature of the civilization and the sophistication of these people. Around 327-326 BCE Alexander the Great invaded India and from 273-232 BCE Ashoka, third ruler of the Mauryan empire, promoted Buddhism and art work along the Silk Road, making it more defined and recognizable.

The Stupa

Stupas took on varying functions over multiple centuries, but they all served as a place of worship for the Buddha in different ways. Trade connects to Buddhism as the geographic locations of the religious institutions aligned with the merchants routes and this most definitely helped spread Buddhist teachings over long distances. There was a connectedness from religion and trade to art and military trade movements. The Amluk Dara Stupa, erected around the 3rd century C.E. was a way point for lots of merchants. The Stupa served as a holy reliquary and the act of making a stupa was religious. Stupas were meant for circumambulation, or walking around the outskirts of the structure in a circular movement as a form of meditation rather than entering, which is quite different compared to other religious structures.

Early Chinese Bronzes

The Bronze Age in China largely consisted of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties. There were artifacts made during these eras such as the Cong of the Neolithic period (10,000-2,000 BCE). These were used for burial tombs, had faces of spirits or deities, and wouldn’t entirely separate humans from animals. During the Shang dynasty, ceremonious vessels were prominent. These vessels would not be for food and liquids, rather, they were for religious rituals as they were spiritually charged vessels. The right to rule was given to those who possessed these because they often stayed within a specific family for centuries as they were difficult to move and suggested powerful rule. The most important component of the vessels was the fact that they served as an intermediary between the ruler and ancestors. Practices from the Bronze work helped create ceramics in mass production. Artists would adopt their old techniques to create such masterpieces like the Terra Cotta soldiers. Chinese art was mainly used for burial practices, the courtly elite, and Buddhism (around 65 CE).

Altars

The use of altars were common during the Sui dynasty, for the emperor was a devout Buddhist. Pictured below is a rectangular, ornamental, green/bronze altar titled “The Western Paradise of Amitabha Buddha.” This altar was used to burn incense and it was a worship item to venerate the Buddha. The altars were delicate and were something only a wealthy individual would own, instead of going to a monastery like other worshippers.

Buddhism Expands to Japan

The Shinto religion in Japan shifted into Buddhism and common themes were present in Japanese works of art. Similarities included the use of Bodhisattvas, skirt ripples, almond halo shaped head pieces, and bun hairdos. The influence extended further as forms of entertainment, music, and images were all representative of Central Asian influences. The Tale of Genji, pictured below in a handscroll, was an iconic depiction of the story and highlights the elaborate artwork in Japan during the Heian period. The ironic story is about a man who pursues lots of women and sleeps with a woman who’s having another man's child. He has to celebrate his wife even though it is not his child. There is a sophistication represented in the layered textiles and there is no facial expression because he is looking at the viewers with shame. The use of neutral, faded colors characterizes the scene as dull and melancholy.

Islamic Architecture

Islam’s religious structure is made up of five pillars of faith (The Profession of Faith, Ritual prayer, Charity, Fasting during Ramadan, and Hajj/ Pilgrimaage to Mecca) The architecture and artwork associated with religion often mimic the beliefs and Islam is no exception. The Taj Mahal had influence from Hindu temples but there were many Islamic-esque traditions as well. The Taj Mahal has a central dome with subsidiary domes and four main towers. The towers resembled minerettes which were common around mosques. The act of Ritual prayer aligns with the structural component of the towers and therefore embodies the use of ritual art.

Slave Trade

It is imperative that we examine the slave trade that existed when studying the Silk Road. Just as elite members would trade beautiful artwork and luxury items, slaves were a part of this trade. The upper class profited the most from slavery and the slaves themselves were treated as a commodity. The Slave trade extended all the way to Dublin, Ireland and crossed bodies of waters. Perhaps the most important thing to keep in mind when thinking about the slave trade is the fact that history is recorded by the winners of society at a given time and the slaves perspective might be misconstrued or irrepresentative of their lives. Therefore, it’s important to examine the slave trade with a critical eye.

Scrolls

Ancient Chinese Scrolls were an important part of the Silk Road as there were influences from one period to the next; from the Neolithic period to the Han dynasty to the Tsang dynasty. Handscrolls and hanging scrolls on silk were most popular during the Tsang dynasty in China. The handscroll was used more like a book than a painting, as they were a religious and almost ceremonious experience. Handscrolls were carefully unbound and analyzed slowly as this was not a regular or daily exercise. Hanging scrolls, on the other hand, were to be looked at regularly and served more as a decoration than ritualistic art. The images in these scrolls were intentional and offered a sense of beauty in simplicity. The artists would take on the tactic of using space to create a sense of emptiness and making colors seem present even when only blank ink was used.

Japanese Art/Architecture

Japanese Zen Buddhism suggests that people who art trying to achieve the ultimate state of “Zen” seek an outside disciple or master who can provide external stimulus and teach them. There is an act of minimalism associated with Japanese meditation and art. There is an act called the “tea ceremony” which is used to strip down distracting thoughts. Forms of simplicity can be found in a variety of Japanese works ranging from paintings like “The Great Wave” to large structures such as “Himeji Castle.” [found below] Furthermore, there was a large religious and spiritual presence in Japanese works. For example, the Forbidden City and other imperial cities would deem their ruler the “Son of Heaven,” and would make sure to choose an astronomically sound date to establish their cities.

Scythian art

Following contacts of metropolitan China with nomadic western and northwestern border territories in the 8th century BCE, gold was introduced from Central Asia, and Chinese jade carvers began to make imitation designs of the steppes, adopting the Scythian-style animal art of the steppes (descriptions of animals locked in combat). This style is particularly reflected in the rectangular belt plaques made of gold and bronze with alternate versions in jade and steatite.[1]

Even though that happened, the correspondence between the "Scythians" as an ethnic group and their material culture is still subject to discussion and research. The subject is part of the broader "nomadic" and "sedentary" debate.

Hellenistic art

Following the expansion of the Greco-Bactrians into Central Asia, Greek influences on Han art have often been suggested (Hirth, Rostovtzeff). Designs with rosette flowers, geometric lines, and glass inlays, suggestive of Hellenistic influences, can be found on some early Han dynasty bronze mirrors.[2][3]

Greco-Buddhist art

Buddhist Art

Symbols of Buddhist art include images of a lion who embodies kingship and power. A wheel can often be found in a Buddhist context, with the “turning wheel” image representing the act of preaching. In addition, many Buddhist sculptures or paintings will have some kind of base with an upside-down lotus flower. There are four noble truths in Buddhism: life is suffering, desire causes suffering, the cause of desire must be overcome, when desire is overcome, there is no more suffering. There is a widely accepted understanding that Buddhism is an effort to escape the world, which is seen as the source of suffering, through good acts of meditation. Hence, many Buddhist art forms revolve around meditative acts. The image of the Buddha holding up one hand, with legs crossed in a reflective state is recognized around the world. Buddhist art was prominent in the Himalayas and pieces like the mandala offered cardinal directions with a place in the world. Tibetan Buddhism was so widespread, it extended all the way up to Russia.

Buddha

The image of the Buddha, originating during the 1st century CE in northern India (areas of Gandhara and Mathura) was transmitted progressively through Central Asia and then China until it reached Japan in the 6th century.[4]

To this day however the transmission of many iconographical details is still visible, such as the Hercules inspiration behind the Nio guardian deities in front of Japanese Buddhist temples, or representations of the Buddha reminiscent of Greek art such as the Buddha in Kamakura.

See also: History of Buddhism, Buddhist art, Greco-Buddhist art

Eastern iconography in the West

Some elements of western iconography were adopted from the East along the Silk Road. The aureole in Christian art first appeared in the 5th century, but practically the same device was known several centuries earlier, in non-Christian art. It is found in some Persian representations of kings and Gods, and appears on coins of the Kushan kings Kanishka, Huvishka and Vasudeva, as well as on most representations of the Buddha in Greco-Buddhist art from the 1st century CE. Another image which appears to have transferred from China via the Silk Road is the symbol of the Three hares, showing three animals running in a circle. It has been traced back to the Sui dynasty in China, and is still to be found in sacred sites in many parts of Western Europe, and especially in churches in Dartmoor, Devon.

Case studies

Shukongoshin

Another Buddhist deity, named Shukongoshin, one of the wrath-filled protector deities of Buddhist temples in Japan, is also an interesting case of transmission of the image of the famous Greek god Herakles to the Far-East along the Silk Road. Herakles was used in Greco-Buddhist art to represent Vajrapani, the protector of the Buddha, and his representation was then used in China and Japan to depict the protector gods of Buddhist temples.[5]

Wind god

Various other artistic influences from the Silk Road can be found in Asia, one of the most striking being that of the Greek Wind God Boreas, transiting through Central Asia and China to become the Japanese Shinto wind god Fūjin.[6]

In consistency with Greek iconography for Boreas, the Japanese wind god holds above his head with his two hands a draping or "wind bag" in the same general attitude. The abundance of hair have been kept in the Japanese rendering, as well as exaggerated facial features.

Floral scroll pattern

Finally, the Greek artistic motif of the floral scroll was transmitted from the Hellenistic world to the area of the Tarim Basin around the 2nd century CE, as seen in Serindian art and wooden architectural remains. It then was adopted by China between the 4th and 6th century, where it is found on tiles and ceramics, and was then transmitted to Japan where it is found quite literally in the decoration of the roof tiles of Japanese Buddhist temples from around the 7th century.[7]

The clearest one are from the 7th century Nara temple building tiles, some of them exactly depicting vines and grapes. These motifs have evolved towards more symbolic representations, but essentially remain to this day in the roof tile decorations of many Japanese traditional-style buildings.

See also

Notes

- "There is evidence of gold belt-plaques with "Scythian" "animal style" art, greaves, barrows and other indications of the penetration of steppe cultures south of the Yangzi before the Han period" (Mallory and Mair "The Tarim Mummies", p.329)

- Zhou bowl: "RED EARTHENWARE BOWL, DECORATED WITH A SLIP AND INLAID WITH GLASS PASTE. Eastern Zhou period, 4th-3rd century BC. This bowl was probably intended to copy a more precious and possibly foreign vessel in bronze or even silver. Glass was little used in China. Its popularity at the end of the Eastern Zhou period was probably due to foreign influence." British Museum notice to the bowl (2005)

- "The things which China received from the Graeco-Iranian world- the pomegranate and other "Chang-Kien" plants, the heavy equipment of the cataphract, the traces of Greeks influence on Han art (such as) the famous white bronze mirror of the Han period with Graeco-Bactrian designs (...) in the Victoria and Albert Museum" (W. W. Tarn, The Greeks in Bactria and India, 1980, pp. 363-364)

- "Needless to say, the influence of Greek art on Japanese Buddhist art, via the Buddhist art of Gandhara and India, was already partly known in, for example, the comparison of the wavy drapery of the Buddha images, in what was, originally, a typical Greek style" (Katsumi Tanabe, "Alexander the Great, East-West cultural contacts from Greece to Japan", p19)

- "The origin of the image of Vajrapani should be explained. This deity is the protector and guide of the Buddha Sakyamuni. His image was modelled after that of Hercules. (...) The Gandharan Vajrapani was transformed in Central Asia and China and afterwards transmitted to Japan, where it exerted stylistic influences on the wrestler-like statues of the Guardina Deities (Nio)." (Katsumi Tanabe, "Alexander the Great, East-West cultural contacts from Greece to Japan", p23)

- "The Japanese wind god images do not belong to a separate tradition apart from that of their Western counter-parts but share the same origins. (...) One of the characteristics of these Far Eastern wind god images is the wind bag held by this god with both hands, the origin of which can be traced back to the shawl or mantle worn by Boreas/ Oado." (Katsumi Tanabe, "Alexander the Great, East-West cultural contacts from Greece to Japan", p21)

- The transmission of the floral scroll pattern from West to East is presented in the regular exhibition of Ancient Japanese Art, at the Tokyo National Museum.

References

- Alexander the Great: East-West Cultural contacts from Greece to Japan. Tokyo: NHK Puromōshon and Tokyo National Museum, 2003.

- Jerry H.Bentley. Old World Encounters: Cross-cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-modern Times. Oxford–NY: Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-19-507639-7

- John Boardman. The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-691-03680-2

- Osmund Bopearachchi, Christian Landes, and Christine Sachs. De l'Indus à l'Oxus : Archéologie de l'Asie centrale. Lattes, France: Association IMAGO & Musée de Lattes, 2003. ISBN 2-9516679-2-2

- Elizabeth Errington, Joe Cribb, & Maggie Claringbull, eds. The Crossroads of Asia: Transformation in Image and Symbols. Cambridge: Ancient India and Iran Trust, 1992, ISBN 0-9518399-1-8

- Richard Foltz. Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of Globalization, 2nd edn. NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. ISBN 978-0-230-62125-1

- J.P. Mallory & Victor Mair. The Tarim Mummies. London: Thames and Hudson, 2000. ISBN 0-500-05101-1

- William Woodthorpe Tarn. The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1951.

External links

- Along the ancient silk routes: Central Asian art from the West Berlin State Museums, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF)