Sidney Hill

Sidney Hill (1 October 1829 – 3 March 1908), born Simon Sidney Hill, was a Methodist, merchant, philanthropist, gentleman farmer, and justice of the peace. From modest beginnings he made his fortune as a colonial and general merchant who pioneered trade from South Africa. He supported and endowed almshouses in Churchill and Lower Langford, and manses for Methodist clergy at Banwell and Cheddar. He built Methodist churches at Port Elizabeth, Sandford, Shipham and Blagdon besides the Wesley Methodist chapel and school at Churchill. Many of his charitable foundations still survive.

Sidney Hill | |

|---|---|

Sidney Hill riding his horse – circa 1890s | |

| Born | Simon Sidney Hill 1 October 1829 Berkeley Place, Clifton, Bristol |

| Died | 3 March 1908 (aged 78) Langford House, Lower Langford, North Somerset |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Ann Bobbett (m. 1864; died 1874) |

Early life

Sidney Hill was born on 1 October 1829, at Berkeley Place in Clifton, Bristol,[1] the fifth and youngest son of Thomas Hill (1778–1846), a former master sweep and soot merchant, and his wife, Elizabeth (1783–1857), née James.[2][n 1] He was baptised at St James' Priory, Bristol on 1 November 1829,[4] and educated at Portway House boarding school, located between Victoria Park and Partis College, in Weston, Bath.[5]

Hill's father, Thomas, was apprenticed as a climbing boy from the age of eight, serving from 1787 to 1798 before joining the Royal Marines at Devonport, Plymouth. He left the navy after four years, returned to sweeping, but left it again to earn a living as a labourer in Devonport Dockyard. He returned to sweeping again in 1811 and followed it until his retirement.[6] He was also a foreman to the Clifton Norwich Union Fire Insurance Office for twelve years, until one of his other sons took over the role.[n 2]

Thomas Hill died on 7 October 1846 (aged 68) when Sidney Hill was just seventeen years old.[8][n 3] In September 1847, Hill joined Sunday Methodist society clasess, led by William Bobbett,[n 4] at the Old Market Street chapel in Bristol. It was there that Hill converted to Methodism and met his life-long friends Thomas Francis Christopher May and William Hunt of Clifton.[10][n 5]

Life as a merchant

Early years

Described as a delicate boy, Sidney Hill did not follow in his father's soot business, although two of his brothers did carry on the business. When he came of age, he inherited money from his father's estate that he used to open a small linen draper shop at Berkeley Place, Clifton.[13][n 6] The business grew and he moved to larger premises at 7 Byron Place, Lower Berkeley Place, Clifton.[15]. However, by 1856 he was not in good health and his doctor advised him to travel to a country with a warmer climate.[3] Hill sold the drapery business and embarked on a sea voyage to New Zealand, but when the ship berthed at Algoa Bay, Port Elizabeth, he decided to remain in South Africa.[16] Unfortunately, the first letter he received there informed him of the death of his mother on 31 March 1857 (aged 73).[17][n 7]

In 1857, Hill opened a dry goods store at Port Elizabeth,[13] and in 1859, went into partnership with William Savage. Savage was the son of a former paper maker and stationer in Lewes, East Sussex. He had arrived in Port Elizabeth around 1849 and started a business selling stationery and hardware. Their partnership, Savage & Hill, Colonial and General Merchants, began trading commodities from 95 and 97 Main Street (southern side) in Port Elizabeth.[19] They traded in anything from household hardware, refined sugar, ammunition, minerals, to ostrich feathers for the fashion trade and haberdashery industry.[20][n 8] The bulk of their trade was transacted from Port Elizabeth, but as the business prospered, branches were opened in the principal towns of the Cape Colony and in the Colony of Natal.[22]

Marriage

In 1864, Hill returned to London to direct the firm's large shipping interests from their offices at 41 Bow Lane, Cheapside, London.[16][n 9] On 15 June 1864, he married Mary Ann Bobbett at the Wesleyan Chapel, Churchill, Somerset.[24][n 10] Mary Ann was born on 6 March 1839, the eldest daughter of John Winter Bobbett (1814–1898) and Frances (1818–1890), née Doubting. John Winter Bobbett was a baker and corn and flour dealer, in partnership with his brother William Bobbett, at W. and J. W. Bobbett, on West Street, Old Market, Bristol.[25][n 4] He was an active radical Liberal in his earlier years, a Quaker, and a former guardian of the Clifton Union.[26]

In 1849, Mary Ann was sent to school; first to the Quaker Friends' Boarding School at Sidcot, near the village of Winscombe, Somerset, and then to a finishing school, the Quaker Mount School in York.[27] She was away from home for five years, and when she returned to Bristol, she became a housekeeper for her uncle, William Bobbett, at West Street, Bristol.[28] Hill had met her a number of years before, when he had been invited to Sunday tea at Bristol, and then at Sidney Villa in Dinghurst, Churchill,[n 11] after William Bobbett had moved there in 1859, following his retirement on 2 July 1859.[30] They shared a staunch belief in the work of the Wesleyan Church, and this would influence much of their life, particularly Hill's later years after he purchased the Langford estate.[20]

Life in South Africa

William Taylor, Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church for Africa, after meeting Hill at his home in Port Elizabeth on 21 April 1866, (Taylor 1896, p. 340)

They spent six months in London before Hill’s business took them back to South Africa, departing England on 10 February 1865 for a month-long voyage to Port Elizabeth.[31] Savage & Hill prospered after the growth of trade at Port Elizabeth following the discovery of diamonds at Griqualand West in 1870, and the subsequent completion of the railway to Kimberley, Northern Cape, in 1873.[32][n 12] With the rapid expansion of the Cape Colony's railway network to the interior over the following years, the harbour of Port Elizabeth became the focus for serving import and export needs of a large area of the Cape's hinterland.[34][n 13]

Despite being engaged in an expanding business, Hill found time for furthering the work of the Wesleyan Methodist church at Port Elisabeth, occupying the offices of superintendent of the Sunday school, class leader, and chapel and circuit steward.[3] In 1870, Hill financed the construction of the original Wesleyan Methodist chapel at Russell Road, Port Elizabeth.[36][n 14]

Death of wife

Around 1870, Mary Ann was diagnosed with tuberculosis in her left lung.[37] With her health failing they left South Africa for England on 8 April 1874.[38] They decided to winter in Bournemouth due to the mild climate there, but after only five weeks' residence, she died at 5:38 pm on 7 December 1874 (aged 35).[39] She was buried at Arnos Vale Cemetery in Bristol.[40] In 1881, her remains were removed from Arnos Vale and reinterred at the Wesleyan Methodist Church, Churchill, that was built in her memory in 1880.[41]

Later life

Return to England

In mourning, Hill returned to South Africa, but could not settle, and in June 1876, he decided to find somewhere to live near Churchill, close to his friend William Bobbett.[3] In mid-1877, Langford House, Lower Langford, came on to the market after the owner, William Turner, had died on 13 November 1876 (aged 58).[42][n 15] Hill purchased the estate and took up residence at the end of October 1877.[3][n 16] The estate included 35 acres (14 hectares) of parkland, 8 acres (3.2 hectares) of orchards, 4 acres (1.6 hectares) of arable land, stabling, and two adjacent, semi-detached houses in Langford village, known as Mendip Villa and Richmond House.[45][n 17]

Hill retired from commercial life after dissolving the Savage & Hill partnership on 1 November 1881.[48] At that point, he had accumulated considerable wealth, and consequently, was able to spend a substantial amount of money making improvements to Langford House. He re-modelled the house, adding a belvedere tower in Italianate style,[n 18] to which he added a turret clock and carillon in November 1891.[n 19] He installed a conservatory and greenhouses, constructed in teak, to provide all the bedding and house plants for the estate.[20][n 20]

Stock breeding

Hill took up a new life as a gentleman farmer, adding stables to the estate, a dairy and Langford Bullock Palaces for his prized Red Scotch Shorthorn cattle.[51][n 21] He was well-known as a breeder of pedigree shorthorn cattle, Southdown sheep, hackney and shire horses. In 1881, he laid the foundation for his herd by purchasing two pedigree Dairy Shorthorns cows, Minerva and Irony, and the pedigree bull Oswald 50118, from Richard Stratton of Duffryn, Newport. However, by 1892 the herd had outgrown their accommodation, and they were sold at auction.[53] Between 1897 and 1898, Hill purchased six cows, that included the pedigree cow Lavender Gem, and her heifer calf Lavender Wreath.[54] The two cows had many offspring, several of which were show prize winners.[55] The whole of the herd was of Scottish origin, apart from some shorthorns purchased from Joseph Dean Willis of Bapton on 30 July 1897.[56] The herd was dispersed shortly after Hill’s death, in an auction held at Langford House on 10 September 1908.[55][n 22]

Furthering the work of the church

Hill did much to further the work of the Methodist church in Somerset and help those in need.[16] In memory of his wife, he built the Memorial Wesleyan Methodist Church and Sunday school at Churchill. He also vested in trustees a large sum of money to provide an income for the maintenance of the chapel and schoolroom. In 1887, he built Victoria Jubilee Homes, and gifted a farm and lands at Congresbury, to provide for repairs and maintenance. Later, in memory of his friend William Bobbett, he built a Methodist chapel at Shipham.[3]

From the 1890s, many Methodists had come from the North of England to be employed at the paper mills in Redcliffe Street, Cheddar, and from South Wales at the shirt factories located in the Cheddar Gorge.[58] Around the mid-1890s, Methodist society leaders at Cheddar, Somerset, began to see the need for larger and more convenient premises. Hill was approached, and two cottages,[n 23] and the garden and orchard behind the existing chapel, were purchased. Then came a manse to replace the one at Axbridge, two ministers' houses on the Worle Road, Banwell, and a furnished chapel at Cheddar. All of these were gifted by Hill including the furnishings for a schoolroom that was created by converting the old chapel. His final act was to build, furnish, and endow twelve Wesleyan Cottage Homes at Churchill.[59]

Other charitable acts

Although a life-long Methodist, Hill helped a number of other Christian institutions such as contributing to Churchill Parish Church funds, donating £100 to the building of All Saints Church, Sandford, and gifting a stained glass window to Axbridge parish church after its restoration in 1887.[62] Hill would also help people directly: He would notice those needing help and make enquiries about them. A note would be given to them to take to the post office in Churchill. The two upstairs rooms were full of household items provided by Langford House. Arthur Carter, the owner of the post office, would follow the instructions in the note and supply blankets, boots, food or whatever was required.[63] At Christmas, children who attended the Methodist Sunday school were given a set of clothes each and the contents of each parcel were noted so that the same things were not included for the following Christmas.[16] On 21 December 1885, Langford House was "besieged" by several hundred people receiving gifts of bread, tea, and sugar. In addition, parcels of clothing and bedding were sent to a large number of people in the parish.[64] Hill was also a long-term supporter of the Bristol Hospital for Sick Children and Women, and would visit the hospital at Christmas, giving money to each patient and nurse.[65]

Public life

On 11 June 1885, Hill was elected a fellow of the Royal Colonial Institute, and by May 1886, he was a steward of the Infant Orphanage Asylum.[66] He was a Liberal in politics and was selected as a vice-president of the Wells Liberal Association on 20 May 1886.[67] On 19 October 1886, he was made a justice of the peace for Somerset and served on the Axbridge bench for over 20 years.[68][n 25] From 1887, he served as the vice-president of the Weston-super-Mare and East Somerset Horticultural Society, and in January of the following year, he accepted the office of president of the society.[69] By January 1890, he had been elected to the Council of the Imperial Federation League.[70] He took lead positions amongst the Wesleyans of the Bristol and Bath district, representing the district at church synods and conferences.[3]

Hill also undertook parish responsibilities such as president of the Churchill football and cricket clubs. He lent a field free of charge for their use and contributed to the finances of each club. He was an organiser for the Jubilee and Coronation celebrations that were hosted in the grounds of Langford House.[3] On 7 February 1899, he was elected vice-president of the Wrington and District Fanciers' Association.[71]

Death and burial

The Reverend William Perkins at Hill's funeral, (Clifton Society 1908, p. 13, March 12)

After returning from church on 26 January 1908, at about 4:00 pm, Hill slipped while walking across the Langford House hallway, fracturing his thigh.[72] His thigh seemed to be healing and the splints were removed after four weeks.[73] However, more serious complications developed; influenza followed by pneumonia, and he died at 11:45 am on 3 March 1908 (aged 78).[3]

His funeral was held at the Wesleyan Methodist Church, Churchill, on 10 March 1908, at 2:00 pm. Despite the cold and windy weather that day, hundreds of people attended from Churchill, Langford, Wrington, and many other villages: Such were the number of mourners that the service had to be held outside the Methodist chapel. The outdoor staff of the Langford House estate, which included the nine gardeners, headed the funeral’s foot procession.[74] The coffin bore the inscription "Simon Sidney Hill, born October 1st, 1829, died March 3rd, 1908" and he was interred in the same grave as his wife.[75]

A memorial service was held at the Methodist Chapel, Cheddar, in the evening of 15 March 1908, and was conducted by Henry John Stockbridge.[76]

Legacy

Langford House was later left to Hill’s nephew Thomas James Hill, but he only lived in it for four years before his death on 9 February 1912. The terms of the will were that the next beneficiary was James Alfred Hill, another nephew, but he had died at Kimberley, Northern Cape, South Africa, on 27 January 1910 (aged 60),[77] so the occupancy was taken up by a great-nephew, Thomas Sidney Hill (known as the "second Sidney Hill").[78] Thomas Sidney Hill died on 25 September 1944 (aged 70), and two years later, the Commissioners of Crown Land bought Langford House, and in 1948 the University of Bristol founded the School of Veterinary Science.[79] Nevertheless, many of Hill's charitable works still survive today; Victoria Jubilee Langford Homes and the Sidney Hill Churchill Wesleyan Cottage Homes are registered charities providing housing for local people in need.[80]

Hill's memory lives on in the rich legacy of buildings that he erected, but he meant more than this to the many late-19th century poor; to many he was the difference between life and death, good health and sickness.[81] The late Ronald Henry Bailey, a former editor of the Weston-super-Mare Mercury newspaper, and an authority on Mendip folklore and other antiquarian matters,[82] described Hill as:

An exceptional man, among the last of the old school of benefactors who, in the days before National Pensions and State Health Services, made life tolerable for unfortunate neighbours when they fell by the wayside. He died just as the social pattern was changing for the better.[83]

Sidney Hill put into practice the beliefs of Wesley; to lead a healthy life doing good, feeding and clothing those in need, earning, saving and giving all he could, seeking justice for all. Furthermore, many of his charitable acts honoured the memory of his late wife, Mary Ann, a devout Methodist, whom he missed deeply after her early death.[81] Nonetheless, Hill's wealth came from trade with southern Africa and it is not certain to what extent his fortune was amassed at the expense of others. On balance, however, it is thought likely that his business dealings as a merchant were without reproach. Certainly, it is clear, that whatever his attitudes as a younger man, he later shared his wealth with the less fortunate.[84]

Philanthropic works

Sidney Hill was prolific in works for the public benefit. He built and endowed the Queen Victoria Memorial Homes in Langford, to benefit those who could not afford to rent decent and safe accommodation. He built several Wesleyan churches, Sunday schools, and ministers' houses in this country and in South Africa, and also furnished and endowed a mother's house for Homes for Little Boys at Swanley, Kent. His final act to benefit the poor was to build, furnish, and endow twelve Wesleyan cottage homes at Churchill.[n 26]

| Building | Location | Type | Opened | Architect | Grade II Listing[l 1] | Geo-coordinates | Image | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methodist Chapel | Russell Road, Port Elizabeth | Methodist chapel | 20 October 1872 | John Thornhill Cook | - | 33.960449°S 25.615253°E |  |

[86] |

| The original Wesleyan Methodist chapel at Russell Road, Port Elizabeth, commenced build in 1870, and the foundation stone was laid by Hill's wife, Mary Ann. She took an active part in fundraising, and Hill gave the site and contributed about one-fifth the entire cost of the schoolroom, chapel, and vestries. The building cost £5,000, and of this, in 1872, when the church was completed, all but £500 was raised. The Reverend James Fish and Hill then persuaded the other merchants in Main Street to donate, and in a few hours, the remaining amount was raised. The Church was opened on 20 October 1872 and Hill later presented a memorial window to the church in memory of his wife.[n 27] | ||||||||

| Methodist Memorial Church and School Room | Churchill | Methodist church | 2 May 1881 | Foster and Wood of Bristol | 1157925 | 51.334336°N 2.800281°W |  |

[88] |

| The church was built in memory of Hill's wife. He also built a hall adjacent to the Church, where he could hold secular meetings, and appointed Endowment Trustees to run it. A porch, funded by Hill, was added in 1898, designed by Foster and Wood of Bristol, and built by Henry Rose of Churchill. | ||||||||

| Mrs. Hill Memorial Cottage | Port Elizabeth | Wesleyan almshouse | January 1883 | John Thornhill Cook | - | 33.961711°S 25.607974°E | [89] | |

| At Hill's request, and in memory of his wife, the Port Elizabeth Ladies' Benevolent Society built a small cottage on the Cape Road.[n 28] It was intended as an almshouse where poor women could live rent-free. It came with four rooms, a small garden, running water, and was capable of accommodating two people. The cottage no longer exists. | ||||||||

| Dames' House | Hextable, Swanley | Cottage homes | 20 July 1883 | Henry Spalding and Patrick Auld | - | 51.414807°N 0.183234°E |  |

[91] |

| Hill funded and furnished a dames' or mother's house for Homes for Little Boys. The Prince and Princess of Wales travelled by special train to open the homes. The site now houses Broomhill Bank and Furness School, Rowhill Road, Hextable, Swanley, Kent. | ||||||||

| Victoria Jubilee Homes | Langford | Wesleyan almshouse | 1891[92] | Joseph Wood of Foster and Wood of Bristol | 1320910 | 51.342625°N 2.772076°W |  |

[93] |

| In commemoration of the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria, and in an effort to benefit the poor around him, Hill acquired and cleared land at Langford, and built and furnished six dwellings known as the Victoria Jubilee Langford Homes. Hill laid the foundation stone on 1 October 1887, his fifty eighth birthday, and invitations to tender for the build were advertised by Foster and Wood on 9 January 1888. Rookery Farm with 65 acres (26 hectares) of land, and a further 22 acres (8.9 hectares) at Smallway, both in Congresbury, were purchased as an endowment to provide income for repairs and to pay the residents of each house a sum of £30 per year towards maintenance. The total cost was £14,300 plus a further £1,300 to reinstate Rookery Farm, and from the endowment, rental totalling £229 per annum was secured. | ||||||||

| Methodist Chapel | Shipham | Methodist chapel | 3 April 1893 | Foster and Wood of Bristol | - | 51.314098°N 2.797838°W |  |

[94] |

| The chapel was dedicated to the memory of William Bobbett, Hill's Methodist class leader in 1847, life-long friend, and his wife's uncle. It was built by Charles Franks of Ubley and George Simmons of Priddy. The chapel is now a private residence. | ||||||||

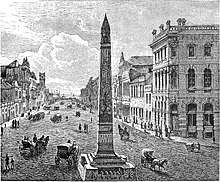

| Jubilee Clock Tower | Churchill | Clock tower | 20 June 1897 | Joseph Foster Wood FRIBA of Foster and Wood of Bristol[n 29] | 1129198 | 51.333995°N 2.799642°W |  |

[96] |

| The clock tower, chimes, and drinking fountain were built to commemorate Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee in 1897.[n 30] In 1976, the clock and chimes were refurbished and renovated by the then trust that managed the clock tower. In the following year, for the Queen's Silver Jubilee, the tower was cleaned by a team of volunteers led by Arthur Raymond Millard ("Ray Millard") BEM, former chairman of Churchill Parish Council. | ||||||||

| Memorial Jubilee Wesleyan Chapel | Cheddar | Methodist chapel | 28 September 1897 | Foster and Wood of Bristol | - | 51.277531°N 2.775901°W |  |

[97] |

Hill funded and furnished a manse and a new chapel. It was built by the local firms of John Scourse and Son and Isaac Ford and Son. The old chapel was converted to a school. Running around the chancel, beneath the east window, is a brass plate bearing the following inscription:

| ||||||||

| Memorial Centenary Wesleyan Chapel | Sandford | Methodist chapel | 11 October 1900 | Foster and Wood of Bristol | 1320686 | 51.329686°N 2.833811°W |  |

[98] |

| The old chapel, next to the chapel that Hill built, was converted into a school. | ||||||||

| Methodist Memorial Chapel and School Room | Blagdon | Methodist chapel | 12 June 1907 | Sir Frank William Wills | - | 51.327079°N 2.719054°W |  |

[99] |

| The chapel was dedicated to the memory of Thomas Francis Christopher May. The foundation stone was laid on 19 October 1906 by May's widow, Ann Reece (née Bowyer). Hill had given £1,500 to fund the building of the chapel. The chapel and school was opened by Hill and a caretaker's cottage was also completed at a later date. The chapel and school are now private residences. | ||||||||

| Sidney Hill Cottage Homes | Churchill | Wesleyan almshouse | December 1907 | Silcock and Reay of Bath and London | 1129199 | 51.335258°N 2.804740°W |  |

[100] |

| Twelve cottages were built, arranged on three sides of a quadrangle, about 37 metres (120 feet) square, with landscaped gardens.[n 31] The third, or south side, was enclosed by a low terrace wall with wrought iron gates. The homes were intended to provide comfortable and furnished homes for the "deserving poor", and a fund was set aside to produce an income of £400 a year for their maintenance. A large stone sundial, with a spreading base, was placed in the centre of the quadrangle.[n 32] Each house had a living room, with a small scullery, larder, coal house, and one bedroom with a large storeroom. The cost of the buildings, including the furniture, the trustees' room, a cottage for the matron,[n 33] a small, but fully-equipped, laundry and other out-buildings, amounted to just under £13,000, with the gardens and planting costing £900. | ||||||||

Notes

| ||||||||

Arms

According to Fox-Davies in Armorial Families (1895), Hill bore:[105]

For Arms: Azure, a chevron nebuly argent, charged with three pallets gules, between two fleurs-de-lis in chief and a talbot's head erased in base of the second. Upon the escutcheon is placed a helmet befitting his degree, with a mantling azure and argent; and for his Crest, upon a wreath of the colours, a talbot's head couped argent, charged with a chevron nebuly, and holding in the mouth a fleur-de-lis azme; with the Motto, "Omne bonum Dei donum".

Stone in The Routledge Dictionary of Latin Quotations (2005), translates the motto, Omne bonum Dei donum, as "Every good thing is a gift of God" and is taken from James, chapter 1, verse 17.[106][n 34]

References

- Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1908, p. 8, March 7; Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1908, p. 2, April 4.

- Thomas Hill Will 1846, pp. 351–352.

- Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1908, p. 8, March 7.

- St James Baptisms 1829, p. 249.

- Census 1841, p. 38; Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette 1837, p. 2, July 13.

- Parliament 1834, pp. 139–140.

- Cullingford 2001, p. 44.

- Bristol Times and Mirror 1846, p. 3, October 10.

- Clifton Burials 1846, p. 205.

- Western Daily Press 1901, p. 9, October 24; Western Daily Press 1924, p. 4, June 10; Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1896, p. 2, July 11.

- Western Daily Press 1905, p. 5, August 10; Western Daily Press 1906, p. 3, October 19; Western Daily Press 1907, p. 8, June 13.

- Western Daily Press 1901, p. 9, October 24.

- Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1908a, p. 2, April 4.

- Thomas Hill Will 1846, p. 352; Cullingford 2001, p. 42.

- Post Office Directory 1856, p. 169; Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1908a, p. 2, April 4.

- Leeming 1977, p. 40.

- Caldecott 1875, p. 15; Bristol Mercury 1857, p. 8, April 4.

- Clifton Burials 1857, p. 205.

- McCleland 2017; Sussex Agricultural Express 1896, p. 5, April 24; Port Elizabeth Directory 1877, p. 223.

- Mako 2013, p. 44.

- Archer 2009, p. 236.

- Sussex Agricultural Express 1896, p. 5, April 24.

- Export Merchant Shippers 1873, p. 289.

- Western Daily Press 1864, p. 3, June 18.

- Western Daily Press 1888, p. 6, May 17.

- Bristol Times and Mirror 1898, p. 8, December 21.

- Caldecott 1875, pp. 5–6.

- Caldecott 1875, pp. 5–6; Leeming 1977, p. 40.

- Cheddar Valley Gazette 1964, p. 6, April 24.

- Caldecott 1875, pp. 9–10; Bristol Mercury 1859, p. 4, July 9; Western Daily Press 1888, p. 6, May 17.

- Caldecott 1875, p. 17.

- Croizat 1967, p. 17; Sussex Agricultural Express 1896, p. 5, April 24.

- Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1908, p. 2, April 4.

- Burman 1984, p. 66.

- Inggs 1986, p. 77.

- Whiteside 1906, p. 126.

- Caldecott 1875, p. 48.

- Caldecott 1875, p. 62.

- Caldecott 1875, p. 63; Bristol Times and Mirror 1874, p. 4, December 9.

- Fryer & Darby 2009, p. 213.

- Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1908, p. 8, March 7; Mako 2013, p. 47.

- Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 1876, p. 5, November 17.

- North Devon Journal 1876, p. 8, May 23.

- Bristol Mercury 1877, p. 5, October 20.

- Western Times 1872, p. 1, June 7.

- Gowar 2009, p. 192. Historic England, "St Mary's and Boundary Railings and Gates (1311718)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 7 June 2020. Historic England, "Richmond House (1129201)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 7 June 2020

- Gowar 2009, p. 201; Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1908b, p. 6, June 27; Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1893, p. 8, October 28.

- Times 1881, p. 11, December 5; "No. 25041". The London Gazette. 25 November 1881. p. 6177.

- Mako 2013, p. 44; Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1891, p. 8, November 28.

- Foster & Pearson 1909, p. 14.

- Mako 2013, p. 44; Western Daily Press 1945, p. 3, July 21.

- Fryer & Darby 2009, p. 210.

- Western Daily Press 1899, p. 7, July 11.

- Aberdeen Press and Journal 1904, p. 3, February 26.

- Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1908c, p. 5, September 12.

- Warminster & Westbury journal 1897, p. 6, July 31.

- Mako 2013, p. 47.

- Wells Journal 1965, p. 4, August 6.

- Wells Journal 1965, p. 4, August 6; Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1897, p. 3, April 3.

- Weston Mercury 1887, p. 8, June 25; Statham 1887, p. 48.

- Western Gazette 1886, p. 8, December 17.

- Leeming 1977, pp. 41–42; Western Daily Press 1884, p. 3, January 11; Statham 1887, p. 48.

- Fryer & Darby 2009, p. 214.

- Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1885, p. 8, December 26.

- Bristol Times and Mirror 1905, p. 17, December 30; Western Daily Press 1907b, p. 9, December 21.

- Colonies and India 1885, p. 24, June 19; Morning Post 1886, p. 4, May 27.

- Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1886, p. 3, May 22.

- Weston Mercury 1886, p. 7, October 23.

- Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1887a, p. 4, July 30; Bristol Mercury 1888a, p. 6, February 1.

- Imperial Federation League 1890, p. 31.

- Weston Mercury 1899, p. 5, February 11.

- Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1908d, p. 8, February 1; Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1908, p. 8, March 7.

- Fryer & Darby 2009, p. 215.

- Western Daily Press 1908, p. 9, March 11.

- Fryer & Darby 2009, p. 216.

- Western Gazette 1908, p. 3, March 20.

- Lunderstedt 2020.

- Fryer & Darby 2009, pp. 217–218.

- Mako 2013, p. 51.

- Victoria Jubilee Langford Homes 2010; Sidney Hill Cottage Homes 2010.

- Archer 2009, p. 234.

- Cheddar Valley Gazette 1960, p. 1, April 22.

- Leeming 1977, p. 42.

- Archer 2009, p. 235.

- Western Daily Press 1882, p. 3, September 29; Gloucester Journal 1909, p. 11, January 30.

- Whiteside 1906, p. 126; McCleland 2016; Humphrey 2017; Weston Mercury 1881, p. 2, May 14.

- McCleland 2016.

- Leeming 1977, pp. 40–41; Weston Mercury 1881, p. 2, May 14.

- Grahamstown Journal 1883, January 16.

- Richmond Hill SRA 2016.

- Morning Post 1883, p. 5, July 21.

- Morris 2009, p. 172.

- Leeming 1977, p. 41; Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1887, p. 8, October 8; Bristol Mercury 1888, p. 4, January 9; Royal Institute of British Architects 1905, p. 583, July 22.

- Western Daily Press 1893, p. 3, April 4.

- Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette 1937, p. 15, September 25.

- Cheddar Valley Gazette 1976, p. 3, October 7; Cheddar Valley Gazette 1977, p. 3, March 10; Royal Institute of British Architects 1917, p. 120; Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette 1937, p. 15, September 25.

- Weston-super-Mare Gazette 1896, p. 2, July 11; Wells Journal 1897, p. 5, September 30.

- Western Daily Press 1900, p. 10, October 13.

- Western Daily Press 1906, p. 3, October 19; Western Daily Press 1907, p. 8, June 13.

- Statham 1907, p. 273; Leeming 1977, p. 40; Western Daily Press 1907a, p. 7, February 20; Holme 1909, p. 218.

- Western Daily Press 1907a, p. 7, February 20.

- Statham 1906, p. 723, June 30; Tate 2004.

- Historic England, "Sundial in inner courtyard at Sidney Hill Cottage Homes (1157960)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 7 June 2020

- Historic England, "Matron's House At Sidney Hill Cottage Homes (1320947)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 7 June 2020

- Fox-Davies 1895, p. 500.

- Stone 2005, p. 189; Bible Hub 2020.

Footnotes

- He styled himself as Sidney Hill and was commonly known by that name in later life.[3]

- Amongst other duties, a foreman would supervise house and chimney fire extinguishment.[7]

- Thomas Hill died at his home in Berkeley Place, Clifton, and was buried at St Andrew's Church, Clifton, on 14 October 1846.[9]

- William Bobbett was a close friend, the leader in the society meetings at Old Market Street chapel, and the uncle of Hill's wife, Mary Ann Bobbett. Hill would later dedicate Shipham Methodist Chapel to the memory of William Bobbett. See Shipham Methodist Chapel under §Philanthropic works.

- Thomas Francis Christopher May was a senior partner of May and Hassall, timber merchants, in the Cumberland Basin, Bristol. He was a prominent Wesleyan and a life-long friend of Hill. He died on 9 August 1905 (aged 74) and the Blagdon Methodist Memorial Chapel and School Room was later dedicated to him.[11]. William Hunt was a leading solicitor in Bristol and a member of Victoria Methodist Church on Whiteladies Road, Clifton.[12]

- Sidney inherited a considerable sum of money and his father's gold watch. Master sweeps could become relatively wealthy if they were able to agree contracts to sweep large estates and public buildings.[14]

- Elizabeth Hill died at Byron Place, Clifton, Bristol, and was buried at St Andrew's Church, Clifton, on 7 April 1857.[18]

- Ostrich feathers were in great demand from the Victorian millinery industry and haberdashers.[21]

- The firm later moved to offices at 42 Palmerston Buildings in Bishopsgate Street.[23]

- They were the first to marry there. The Reverend William Shaw Caldecott, the author of Mary Ann's memorial sketch, was Hill's best man.[24]

- 51.333108°N 2.803435°W. Close to the old Methodist chapel in Churchill and opposite The Drive, Dinghurst. It was renamed Bay Tree House when the Millward family purchased the house from the Richard Stuart Turner Westlake estate in 1984.[29]

- In one year, Hill would report a net profit of £60,000.[33]

- The rapid economic development around the port, which followed the railway construction, caused Port Elizabeth to be nicknamed "the Liverpool of South Africa", after the major British city and port.[35]

- See Port Elizabeth Methodist Chapel under §Philanthropic works

- A partner of Turner, Edwards and Co., wine shipping agents of Bristol.[43]

- Hill was living at William Bobbett's home, Sidney Villa in Dinghurst, Churchill, until he moved into Langford House.[44]

- Both houses are Grade II listed. Mendip Villa is now known as St Mary's House.[46] Mendip Villa was let to Hill's sister, Elizabeth Tapscott, and her daughter, Charlotte Elizabeth, and Richmond House was let to Mary Jane Stone, Elizabeth Tapscott's elder daughter.[47]

- (Pevsner 1958, p. 165) describes Langford house as "an ambitious Italianate villa of circa 1850, with the indispensable asymmetrically placed tower; wings were added later". Langford house is Grade II Listed by Historic England, "Langford House (1157974)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 7 June 2020

- The clock chimed the quarter hours and played All Things Bright and Beautiful on the hour. The clock and carillon were supplied and fixed by M. Michiels of Mélins, Belgium.[49]

- The conservatory and greenhouses were manufactured and installed by Foster and Pearson of Beeston, Nottinghamshire.[50]

- The sheds Hill built for the Shorthorns were called Bullock Palaces as each animal had its own housing with a dormer window and other modern conveniences.[52]

- There is a memorial stone at the southern end of the lawn at Langford House. It remembers Hill's first cow, named Crummy, "a docile creature and good milker", who died in 1888 aged eleven. The stone also records several much-loved dogs, namely Lion, Leo, Glen and Captain.[57]

- One of the cottages stood where the chapel entrance gates are now.[58]

- The church of St John the Baptist, Axbridge, re-opened after its restoration on 24 June 1887 (Midsummer's Day). The stained glass window is set in the east end of the church and was made by Messrs. Bell & Sons, of Bristol. The four lights represent respectively the Nativity, Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Feed my Lambs, the divisions of the tracery being occupied by figures of the Four Evangelists, with their symbols, and Moses and Elijah, a central division containing the "Agnus Dei" emblem of St John the Baptist and arms of the town.[60]. The Rector of Axbridge, Reverend Henry Toft, selected the design.[61]

- After imposing a heavy fine as an example to others, he would often pay it himself, on condition that the accused promised to reform, abstain from alcohol, and from time to time, report to the police.[3]

- Hill also donated substantial amounts of money to aid the Wesleyan cause: £500 to help build the Wesleyan chapel at Linden Road, Clevedon, and after his death, Hill's estate donated £1,500 to fund the building of the Wesleyan Mission Hall at Seymour Road, Gloucester.[85]

- The chapel was closed on 7 December 1969 and demolished for road works. The replacement church, Centenary Methodist Church, designed by Garth Robertson, was opened on 14 December 1969.[87]

- The Port Elizabeth Ladies' Benevolent Society, formerly the Dorcas Society, was founded to "relieve cases of distress and destitution ... and especially to assist aged and infirm persons with young children".[90]

- Joseph Foster Wood was the son and nephew of the founders of Foster & Wood.[95]

- The following is inscribed around the tower: "JUNE 20 1897 THIS TOWER & CLOCK WAS ERECTED BY SIDNEY HILL JP OF LANGFORD HOUSE IN THIS PARISH TO COMMEMORATE THE SIXTY YEARS OF THE BENEFICENT REIGN OF HER MOST GRACIOUS MAJESTY QUEEN VICTORIA"

- The architect's coloured drawing of the homes was sufficiently well-regarded to be included in the 1906 Royal Academy Exhibition.[101] It was said to be inspired by the painting "Harbour of Refuge", painted in 1872 by Frederick Walker, and now in the Tate Gallery.[102]

.jpg) The Harbour of Refuge by Frederick Walker (1872)

The Harbour of Refuge by Frederick Walker (1872) - The sundial is listed separately by Historic England.[103]

- The matron's cottage is also listed separately by Historic England.[104]

- For an image of the Hill arms, see (Fox-Davies 1895, p. 1265, image 5, plate 92)

Bibliography

Books and journals

- Archer, Peter (2009). "25. Simon Sidney Hill". In Fryer, Jo; Gowar, John; et al. (eds.). More Stories From Langford: History and tales of houses and families. Lower Langford: Langford History Group. pp. 233–246. ISBN 978-0-9562253-1-3. OCLC 743449641.

- Burman, Jose (1984). Early railways at the Cape. Cape Town: Human & Rousseau. ISBN 978-0-7981-1760-9. OCLC 12751449.

- Caldecott, Rev. William Shaw (1875). A Modern Phoebe; being a memorial sketch of the late Mrs. Sidney Hill. London: Elliot Stock. OCLC 1064627083. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Croizat, Victor John (1967). The economic development of South Africa in its political context. Santa Monica, California: Rand Corporation. OCLC 651865912. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Cullingford, Benita (2001). British Chimney Sweeps: Five centuries of chimney sweeping. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 978-1-56663-345-1. OCLC 1041488182. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Dean and Son (1873). The Export Merchant Shippers of London. London. p. 289. OCLC 45001919. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Foster, Robert; Pearson, John (1909). Glasshouses and Coldframes (PDF). Beeston: Foster & Pearson Ltd. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (1895). Armorial Families. A complete peerage, baronetage, and knightage, and a directory of some gentlemen of coat-armour, and being the first attempt to show which arms in use at the moment are borne by legal authority. Edinburgh: T. C. & E. C. Jack, Grange Publishing Works. hdl:2027/coo1.ark:/13960/t0bv81w2k. OCLC 3588083.

- Fryer, Jo; Darby, Jean (2009). "25. Langford House". In Fryer, Jo; Gowar, John; et al. (eds.). Every house tells a story: A history of some of Langford's older houses and the people who lived in them. Lower Langford: Langford History Group. pp. 207–221. ISBN 978-0-9562253-0-6. OCLC 751457329.

- Gowar, John (2009). "23. St Mary's House and Richmond House". In Fryer, Jo; Gowar, John; et al. (eds.). Every house tells a story: A history of some of Langford's older houses and the people who lived in them. Lower Langford: Langford History Group. pp. 191–202. ISBN 978-0-9562253-0-6. OCLC 751457329.

- Holme, Charles, ed. (1909). International Studio an Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art. March to June 1909. Numbers 145 to 148. 37. New York: John Lane Co. pp. 217–221. OCLC 1046964405. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Imperial Federation League (1890). "Council of the London Imperial Federation League". Journal of the Imperial Federation League. January to December 1890. London: Cassell & Company Limited. 5: 31. OCLC 1046647221. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Inggs, Jon (1986). "Liverpool of the Cape. Port Elizabeth trade 1820–70". South African Journal of Economic History. South Africa. 1: 77–98. doi:10.1080/20780389.1986.10425071.

- Leeming, Charles Frederick (1977). Langley, Peter (ed.). Langford and Churchill Guide. Sir John Wills. Churchill: Cliftonprint. OCLC 852053375.

- Mako, Marion (2013). "Langford House". The University of Bristol Historic Gardens (PDF) (2 ed.). Bristol: University of Bristol. pp. 42–51. ISBN 978-0-9561001-5-3. OCLC 982673700. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Morris, Joy (2009). "20. The Victoria Jubilee Homes". In Fryer, Jo; Gowar, John; et al. (eds.). Every house tells a story: A history of some of Langford's older houses and the people who lived in them. Lower Langford: Langford History Group. pp. 171–174. ISBN 978-0-9562253-0-6. OCLC 751457329.

- Parliament, House of Lords (21 June 1834). "Evidence on the Chimney Sweepers Regulation Bill". Reports Part 1. Great Britain. 23: 139–144. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

The Duke of Sutherland in the Chair.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1958). North Somerset and Bristol. The Buildings of England. 13. Harmsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140710137. OCLC 1043342766.

- Royal Institute of British Architects (22 July 1905). "The late Joseph Wood". Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Third. Royal Institute of British Architects. 12: 583. ISSN 0035-8932. OCLC 1764591. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- Royal Institute of British Architects (March 1917). "Joseph Foster Wood: Memoir". Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Third. Royal Institute of British Architects. 24: 120. ISSN 0035-8932. OCLC 1764591. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- Statham, Henry Heathcote, ed. (1887). "Church Building News. Axbridge". The Builder. July to September 1887. London: Wyman & Sons. 53. ISSN 0366-1059. OCLC 2942596. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Statham, Henry Heathcote, ed. (1906). "Architecture at the Royal Academy.-IV". The Builder. January to June 1906. London: Windsor House Printing Works. 90. ISSN 0366-1059. OCLC 2942596. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- Statham, Henry Heathcote, ed. (1907). "National Picture Collections". The Builder. January to June 1907. London: Windsor House Printing Works. 92. ISSN 0366-1059. OCLC 2942596. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Stone, Professor Jon R. (2005). The Routledge Dictionary of Latin Quotations: The Illiterati's Guide to Latin Maxims, Mottoes, Proverbs, and Sayings. London & New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. ISBN 978-0415969086. OCLC 469421034. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Taylor, William (1896). Ridpath, John Clark (ed.). Story of My Life. An Account of What I Have Thought and Said and Done in My Ministry of More than Fifty-Three Years in Christian Lands and Among the Heathen. Frank Beard. New York: Hunt & Eaton. OCLC 152584525. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Whiteside, Reverend Joseph (1906). History of the Wesleyan Methodist Church of South Africa. London: Elliot Stock. OCLC 1113337571. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

Newspapers and directories

- "Portway House School". Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette. 13 July 1837. p. 2. OCLC 1016318847. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Deaths". Bristol Times and Mirror. 10 October 1846. p. 3. OCLC 2252826. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

Oct. 7, at his residence, Berkeley-place, Clifton, Mr. Thomas Hill, aged 69, highly respected by all who knew him, and deeply lamented by his numerous family – his end was peace.

- "Deaths". Bristol Mercury. 4 April 1857. p. 8. OCLC 751622486. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

March 31, at Byron-place, Clifton, Mrs. Elizabeth Hill, relict of the late Mr. Thos. Hill, of Berkeley-place, Clifton, aged 73.

- "Notice of partnership dissolution". Bristol Mercury. 9 July 1859. p. 4. OCLC 751622486. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "Churchill". Western Daily Press. 18 June 1864. p. 3. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Postponement of Sale. Somersetshire". Western Times. 7 June 1872. p. 1. OCLC 866859314. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "Deaths". Bristol Times and Mirror. 9 December 1874. p. 4. OCLC 2252826. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

December 7, at Bournemouth, aged 35, Mary Ann, wife of Sidney Hill, merchant, of London, and Port Elizabeth, South Africa, and eldest daughter of J. W. Bobbett, cornfactor, Bristol.

- "Deaths". North Devon Journal. 16 November 1876. p. 8. OCLC 1135530633. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Deaths". Exeter and Plymouth Gazette. 17 November 1876. p. 5. OCLC 751669657. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Port Elizabeth Directory (1877). The Port Elizabeth directory and guide to the Eastern province of the Cape of Good Hope for 1877. Port Elizabeth: J. W. C. Mackay & Co. OCLC 81636479. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Cape of Good Hope". Bristol Mercury. 20 October 1877. p. 5. OCLC 751622486. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

Wanted, an assistant in the Drapery Department of a Wholesale House ... Wesleyan preferred.-Apply S H, Sidney-villa, Churchill, near Bristol.

- "Churchill. The New Wesleyan Memorial Chapel". Weston Mercury. 14 May 1881. p. 2. OCLC 751662463. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "Money-Market and City Intelligence". The Times (30369). 5 December 1881. p. 11. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "New Wesleyan Chapel, School, and Manse at Clevedon". Western Daily Press. 29 September 1882. p. 3. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "The Prince and Princess of Wales at Swanley". Morning Post. 21 July 1883. p. 5. OCLC 72823345. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Church Consecration at Sandford. Sermon by the Bishop of Bath and Wells". Western Daily Press. 11 January 1884. p. 3. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "New Members". Colonies and India. 19 June 1885. p. 24. OCLC 751752305. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Churchill. Christmas Gifts". Weston-super-Mare Gazette, and General Advertiser. 26 December 1885. p. 8. OCLC 751660952. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Public meeting in favour of Home Rule". Weston-super-Mare Gazette, and General Advertiser. 22 May 1886. p. 3. OCLC 751660952. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "List of Stewards". Morning Post. 27 May 1886. p. 4. OCLC 72823345. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Somerset Quarter Session. New Magistrates". Weston Mercury. 23 October 1886. p. 7. OCLC 751662463. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Axbridge". Western Gazette. 17 December 1886. p. 6. OCLC 14708041. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Re-opening of Axbridge Church". Weston Mercury. 25 June 1887. p. 8. OCLC 751662463. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "The Weston-super-Mare & East Somerset Horticultural society". Weston-super-Mare Gazette, and General Advertiser. 30 July 1887. p. 4. OCLC 751660952. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Langford. Birthday Commemoration". Weston-super-Mare Gazette, and General Advertiser. 8 October 1887. p. 8. OCLC 751660952. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Notices". Bristol Mercury. 9 January 1888. p. 4. OCLC 751622486. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

To builders. Tenders are required for the erection of six homes, to be built at Langford, twelve miles from Bristol.

- "District News. Weston-super-Mare". Bristol Mercury. 1 February 1888. p. 6. OCLC 751622486. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "A Golden Wedding". Western Daily Press. 17 May 1888. p. 6. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "Langford. A new clock tower". Weston-super-Mare Gazette, and General Advertiser. 28 November 1891. p. 8. OCLC 751660952. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "New Memorial Wesleyan Chapel Shipham". Western Daily Press. 4 April 1893. p. 3. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "The funeral of the late Mrs Elizabeth Tapscott (Mr Sidney Hill's sister)". Weston-super-Mare Gazette, and General Advertiser. 28 October 1893. p. 8. OCLC 751660952. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Death of Mr. William Savage". Sussex Agricultural Express. 24 April 1896. p. 5. OCLC 1154272925. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Cheddar. Wesleyan extension scheme". Weston-super-Mare Gazette, and General Advertiser. 11 July 1896. p. 2. OCLC 751660952. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Banwell. Wesleyan circuit". Weston-super-Mare Gazette, and General Advertiser. 3 April 1897. p. 3. OCLC 751660952. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "Mr. J. Deane Willis's Shorthorns. Sale at Bapton Manor". Warminster & Westbury journal, and Wilts County Advertiser. 31 July 1897. p. 6. OCLC 749973027. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "Cheddar. Opening of a new chapel". Wells Journal. 30 September 1897. p. 5. OCLC 1065219374. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Obituary. Mr. John Winter Bobbett". Bristol Times and Mirror. 21 December 1898. p. 8. OCLC 2252826. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "Wrington and District Fanciers' Association". Weston Mercury. 11 February 1899. p. 5. OCLC 751662463. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "A Well Known Shorthorn Breeder". Western Daily Press. 11 July 1899. p. 7. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Sandford. New Memorial Chapel". Western Daily Press. 13 October 1900. p. 10. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Old Market Street Wesleyan Chapel. The Bazaar at Redland". Western Daily Press. 24 October 1901. p. 9. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Revival of the Lavender Tribe of Shorthorns". Aberdeen Press and Journal. 26 February 1904. p. 3. OCLC 52441752. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "Death of Mr T. F. C. May". Western Daily Press. 10 August 1905. p. 5. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "The Children's Hospital". Bristol Times and Mirror. 30 December 1905. p. 17. OCLC 2252826. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "The New Wesleyan Chapel Blagdon". Western Daily Press. 19 October 1906. p. 3. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Churchill Cottage Homes : Sidney Hill's Gift". Western Daily Press. 20 February 1907. p. 7. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "New Wesleyan Chapel At Blagdon. Opening Ceremony". Western Daily Press. 13 June 1907. p. 8. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Bristol Hospital for Sick Children and Women". Western Daily Press. 21 December 1907. p. 9. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Accident to Mr. Sidney Hill, J.P.". Weston-super-Mare Gazette, and General Advertiser. 1 February 1908. p. 8. OCLC 751660952. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "Death of Mr. Sidney Hill, J.P.". Weston-super-Mare Gazette, and General Advertiser. 7 March 1908. p. 8. OCLC 751660952. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

A well-known philanthropist.

- "Funeral of Mr. Sidney Hill, J.P.". Western Daily Press. 11 March 1908. p. 9. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

A well-known philanthropist.

- "Funeral of the late Mr. Sidney Hill, J.P.". Clifton Society. 12 March 1908. p. 13. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Cheddar. Memorial Service". Western Gazette. 20 March 1908. p. 3. OCLC 14708041. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "The Late Mr. Sidney Hill's Estate". Weston-super-Mare Gazette, and General Advertiser. 4 April 1908. p. 2. OCLC 751660952. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "Will of the Late Mr. Sidney Hill". Weston-super-Mare Gazette, and General Advertiser. 27 June 1908. p. 6. OCLC 751660952. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "The Late Mr. Sidney Hill's Cattle. Sale of the entire herd". Weston-super-Mare Gazette, and General Advertiser. 12 September 1908. p. 5. OCLC 751660952. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "The New Wesleyan Hall". Gloucester Journal. 30 January 1909. p. 11. OCLC 949912905. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Death of Mr H. C. Perry. Loss to Bristol Methodism". Western Daily Press. 10 June 1924. p. 4. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Married Three Weeks. Death of Mr. G. Awdry, of Bathford". Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette. 25 September 1937. p. 15. OCLC 1016318847. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "O'er Hill and Dale". Western Daily Press. 21 July 1945. p. 3. OCLC 949912923. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Weston Editor's death". Cheddar Valley Gazette. 22 April 1960. p. 1. ISSN 0963-2867. OCLC 500333072. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Gardens open to the public". Cheddar Valley Gazette. 24 April 1964. p. 6. ISSN 0963-2867. OCLC 500333072. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "Cliff Street Holds Variety of Interests". Wells Journal. 6 August 1965. p. 4. OCLC 1065219374. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Councillors to tidy up round Churchill clock". Cheddar Valley Gazette. 7 October 1976. p. 3. ISSN 0963-2867. OCLC 500333072. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "The Jubilee clean up for Jubilee Clock". Cheddar Valley Gazette. 10 March 1977. p. 3. ISSN 0963-2867. OCLC 500333072. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

Websites

- "Post Office Directory of Gloucestershire, Bath & Bristol". specialcollections.le.ac.uk. Kelly and Co. 1856. p. 169. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Memorial Cottage". eGSSA. Genealogical Society of South Africa. 16 January 1883. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Tate (September 2004). "The Harbour of Refuge by Frederick Walker, 1872". Tate. London. N01391. Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "The Sidney Hill Churchill Wesleyan Cottage Homes". Charity Commission. 3 March 2010. 201051. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "The Victoria Jubilee Langford Homes". Charity Commission. 25 August 2010. 230158. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "Ladies' Benevolent Society". Richmond Hill SRA. The Richmond Hill Special Rates Non-Profit Company. 2016. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- McCleland, Dean (31 August 2016). "Port Elizabeth of Yore: Russell Road Methodist Church – 1872 to 1966". The Causal Observer. South Africa. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- McCleland, Dean (5 May 2017). "Port Elizabeth of Yore: Main Street in the Early Days". The Causal Observer. Anthony Scallan. South Africa. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Humphrey, Gerald (August 2017). "Wesleyan Chapel, Port Elizabeth, Eastern Cape". www.artefacts.co.za. Port Elizabeth. Archived from the original on 22 July 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Lunderstedt, Steve (27 January 2020). "Today In Kimberley's History". kimberley.org.za. Kimberley. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

James Alfred Hill

- Bible Hub (26 June 2020). "James 1:17". Biblehub. Archived from the original on 5 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

New King James Version. Every good gift and every perfect gift is from above.

Archives

- Baptisms register. Records of the Anglican parish of St James: 1174–1984 (Digital Image). Baptism registers. Bristol: Bristol Archives. 1826–1830. p. 249. P.StJ/R/2/d. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Burial register. Records of the Anglican parish of St Andrew, Clifton: 1538–1951 (Digital Image). Burial registers. Bristol: Bristol Archives. 1847–1861. p. 205. P/StA/R/5/c. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Burial register. Records of the Anglican parish of St Andrew, Clifton: 1538–1951 (Digital Image). Burial registers. Bristol: Bristol Archives. 1826–1847. p. 86. P/StA/R/5/b. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Will of Thomas Hill, Soot Merchant of Clifton Bristol, Gloucestershire. PROB 11/2046. Volume number: 18 Quire numbers: 851–900 (Digital Image). PROB 11. Prerogative Court of Canterbury and related Probate Jurisdictions: Will Registers. Kew: The National Archives. 8 December 1846. pp. 348–353. PROB 11/2046/295. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- 1841 England, Wales & Scotland Census. Hundred: Bath Forum Parish: Weston. 1 volume, book number 22, folio number 38 (Digital Image). 1841 England, Wales & Scotland Census. Kew: The National Archives. 1841. p. 38. HO 107/931. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

Further reading

- "Advert: Scholastic Establishment, Portway House". The Bathonian. Bath: Pocock, Godwin, Hayward, Russell (1): 2. January 1849. OCLC 557345818. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Hodges, Michael A. (1996). Churchill: A Brief History of the area of the Civil Parish (Revised 13 September 1996 ed.). Wrington: West Country Design. OCLC 31076058.

- Mendelssohn, Sidney (1979). A South African bibliography to the year 1925 [N Suid-Afrikaanse bibliografie tot die jaar 1925]. Being a revision and continuation of Sidney Mendelssohn's South African bibliography (1910). 2. London: Mansell. p. 559. ISBN 978-0-7201-0815-6. OCLC 5125424.

- Stell, Christopher; Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England (1 November 1991). An Inventory of Nonconformist Chapels and Meeting Houses in South-west England. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 978-0113000364. OCLC 1042832755.

- Turrell, Robert Vicat (1987). "Merchants, mining capitalists, and the state". Capital and labour on the Kimberley diamond fields 1871–1890. 54 African studies series. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 59–66. ISBN 978-0-521-33354-2. OCLC 1101008841. Retrieved 5 June 2020.