Shark anatomy

Shark anatomy differs from that of bony fish in a variety of ways. Variation observed within shark anatomy is a potential result of speciation and habitat variation

Skeleton

The skeleton of a shark is mainly made of cartilage. In particular, the endoskeletons are made of unmineralized hyaline cartilage which is more flexible and less dense than bone, thus making them expel less energy at high speeds. Each piece of skeleton is formed by an outer connective tissue called the perichondrium and then covered underneath by a layer of hexagonal, mineralized blocks called tesserae.[1]

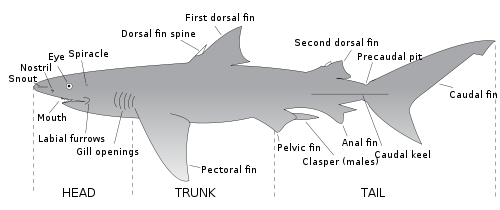

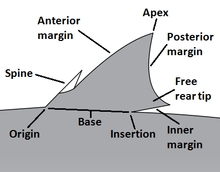

Fins

Most sharks have eight fins: a pair of pectoral fins, a pair of pelvic fins, two dorsal fins, an anal fin, and a caudal fin. The members of the order Hexanchiformes have only a single dorsal fin. The anal fin is absent in the orders Squaliformes, Squatiniformes, and Pristiophoriformes. Shark fins are supported by internal rays called ceratotrichia.

Tail

The tail of a shark consists of the caudal peduncle and the caudal fin, which provide the main source of thrust for the shark. Most sharks have heterocercal caudal fins, meaning that the backbone extends into the (usually longer) upper lobe. The shape of the caudal fin reflects the shark's lifestyle, and can be broadly divided into five categories:

- Fast-swimming sharks of open waters, such as the mackerel sharks, have crescent-shaped tails with upper and lower lobes of almost equal size. The high aspect ratio of the tail serves to enhance swimming power and efficiency. In these species, there are usually also lateral keels on the caudal peduncle. The whale shark and basking shark also have this type of tail, although they are generally more sedate animals than the other examples.

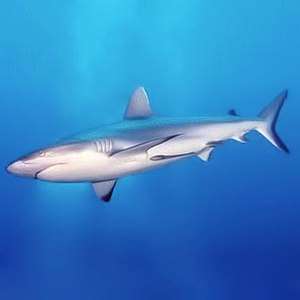

- "Typical sharks", such as requiem sharks, have tails with the upper lobe longer than the lower. The upper lobe is turned upwards at a moderate angle relative to the body, which balances cruising efficiency with turning ability. The thresher sharks have an extreme example of this tail in which the upper lobe has evolved into a weapon for stunning prey.

- Bottom-dwelling sharks such as catsharks and carpet sharks have tails with long upper lobes and virtually no lower lobe. The upper lobe is held at a very low angle, which sacrifices speed for maneuverability. These sharks generally swim with eel-like undulations.

- Dogfish sharks also have tails with longer upper than lower lobes. However, the backbone runs through the upper lobe at a lower angle than the lobe itself, reducing the amount of downward thrust produced. Their tails cannot sustain high speeds, but combine the capability for bursts of speed with maneuverability.

- Angel sharks have unique tails among sharks. Their caudal fins are reverse heterocercal, with the lower lobe larger than the upper.[2]

Integument

Unlike bony fish, the sharks have a complex dermal corset made of flexible collagenous fibres and arranged as a helical network surrounding their body. This works as an outer skeleton, providing attachment for their swimming muscles and thus saving energy. A similar arrangement of collagen fibres has been discovered in dolphins and squid. Their dermal teeth give them hydrodynamic advantages as they reduce turbulence while swimming.

Camouflage

Sharks may have a combination of colors on the surface of their body that results in the camouflage technique called countershading. A darker color on the upper side and lighter color on the underside of the body helps prevent visual detection from predators. (For example, white on the bottom of the shark blends in with the sunlight from the surface when viewed from below.)[3][4] Countershading can also be accomplished through bioluminescence in the few shark species that produce and emit light, such as the kitefin shark, a species of dogfish shark. The species migrates vertically and the arrangement of light-producing organs called photophores provides ventral countershading.[5][6]

Some species have more elaborate physical camouflage that assists them with blending into their surroundings. Wobbegongs and angelsharks use camouflage to perform ambush predation.[7]

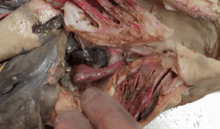

Circulatory system

Sharks possess a single-circuit circulatory system centered around a two chambered heart. Blood flows from the heart to the gills where it is oxygenated. This oxygen-rich blood is then carried throughout the body and to the tissues before returning to the heart. As the heart beats, deoxygenated blood enters the sinus venosus. The blood then flows through the atrium to the ventricle, before emptying into the conus arteriosus and leaving the heart.[8]

Respiratory system

Like other fishes, sharks extract oxygen from water as it passes over their gills. The water enters through the mouth, passes into the pharynx, and exits through the gill slits (most sharks have five pairs, the frilled sharks, cow sharks, and sixgill sawshark have six or seven pairs). Most sharks also have an accessory respiratory opening called a spiracle behind their eyes. In bottom-dwelling sharks such as angel sharks, the spiracle allows them to take in water to breathe without having to open their mouths .

There are two mechanisms that sharks can use to move water over their gills: in buccal pumping, the shark actively pulls in water using its buccal muscles, while in ram ventilation, the shark swims forward, forcing water into its mouth and through its gills. As buccal pumping is more energy-intensive than ram ventilation, the former is generally used by sedentary, bottom-dwelling sharks while the latter is used by more active sharks. Most sharks can switch between these mechanisms as the situation requires. A few species, such as the great white shark, have lost the ability to perform buccal pumping and thus will suffocate if they stop moving forward.[9]

See also

References

- Dean, Mason N.; Mull, Chris G.; Gorb, Stanislav N.; Summers, Adam P. (September 2009). "Ontogeny of the tessellated skeleton: insight from the skeletal growth of the round stingray Urobatis halleri". Journal of Anatomy. 215 (3): 227–239. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01116.x. PMC 2750757. PMID 19627389.

- Thomson, K.S.; Simanek, D.E. (1977). "Body form and locomotion in sharks". American Zoologist. 17 (2): 343–354. doi:10.1093/icb/17.2.343.

- Murphy, Julie (2013). Whale sharks. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Cherry Lake Pub. p. 12. ISBN 9781624314490. OCLC 829445997.

- Heithaus, M.; Dill, L.; Marshall, G.; Buhleier, B. (October 5, 2001). "Habitat use and foraging behavior of tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) in a seagrass ecosystem". Marine Biology. 140 (2): 237–248. doi:10.1007/s00227-001-0711-7. ISSN 0025-3162.

- Reif, Wolf-Ernst (June 1985). "Functions of Scales and Photophores in Mesopelagic Luminescent Sharks". Acta Zoologica. 66 (2): 111–118. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6395.1985.tb00829.x. ISSN 1463-6395.

- Bailly, Nicolas (2014). Bailly N (ed.). "Dalatias Rafinesque, 1810". FishBase. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- Martin, R. Aidan. "Order Orectolobiformes: Carpet Sharks—39 species". ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved 2009-08-29.

- Kardong, K. Zalisko, E. (2006). Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy: A laboratory dissection guide. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Companies.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Edmonds, M. (2008-06-09). "Will a shark drown if it stops moving?". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved April 28, 2013.