Sexual victimization of Native American women

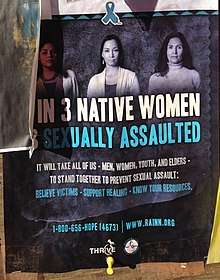

In the United States, Native American women are more than 2.5 times more likely to experience sexual violence than any other ethnicity.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Indigenous rights |

|---|

| Rights |

| Governmental organizations |

| NGOs and political groups |

| Issues |

| Legal representation |

| Category |

In most cases the FBI investigates the crime and the office of the United States Attorney decides whether to prosecute as opposed to tribal law enforcement.[2]

Recognizing sovereignty and affording Native tribes the right to prosecute non-Natives who commit crimes against Native Americans on reservations has been called an extremely important first step in a series of legal changes that would affect how these violations are responded to and viewed at the community, state, and federal level.[3]

Definition

Sexual violence is any sexual act or attempt to obtain a sexual act by violence or coercion, acts to traffic a person or acts directed against a person's sexuality, regardless of the relationship to the victim.[4][5][6] The World Health Organization (WHO) in its 2002 World Report on Violence and Health defined sexual violence as: "any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed, against a person's sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work".[4] WHO's definition of sexual violence includes but is not limited to rape, which is defined as physically forced or otherwise coerced penetration of the vulva or anus, using a penis, other body parts or an object. Sexual violence consists in a purposeful action of which the intention is often diminish human dignity of the victim(s) and to inflict severe humiliation on them. In the case where others are forced to watch acts of sexual violence, such acts aim at intimidating the larger community.[7]

Rape in the United States is defined by the Department of Justice as "Penetration, no matter how slight, of the anus or vagina with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim." While terminology and definitions of rape vary by jurisdiction in the United States, the FBI revised its definition to eliminate a requirement that the crime involve an element of force.[8]

Statistics and data

Amnesty International's "Maze of Injustice" Report

Amnesty International published "Maze of Injustice: the failure to protect indigenous women from sexual violence in the USA",[9] in order to represent the voices of survivors of sexual violence. The research was done for the report in 2005 and 2006 in three different locations with different policing and juridical arrangements. Those locations include Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North and South Dakota, state of Oklahoma, and the state of Alaska.[9] Amnesty International interviewed victims of sexual assault, tribal, state, and federal law enforcement officials, prosecutors and tribal judges for the report. While finding officials to interview for the report, the Executive Office of US Attorneys told them individual US attorneys cannot participate in the survey.

The report opens with the story of a young Alaskan Native woman raped by a non-native man. In July 2006, the woman was raped and rushed to the ER where she was treated as a drunk. They later sent her to a non-native shelter for women where she was also treated as a drunk because of her trauma (Maze of Injustice, 1). Most Native women don't report their assaults because of the fear nothing will be done. Another story that the article reported was the story of a 21-year Native women who was raped by four men in later died in 2003. The case was closed because of questioning of jurisdictions (Maze of Injustice, 6). Each women that shared her story in the report had a common element in their stories. The injustice these women faced were mainly based on stereotypes. Rather their trials took place on a Federal or State level the women were viewed as drunks and some blame was put on them.

When pursuing justice women go through a maze between tribal, state and federal law. The women are first asked "was it in our jurisdiction and was the perpetrator Native American?" when they first contact the police department. It takes a lot of time just to have your case heard so women give up (Maze of Injustice 8). The Amnesty International report go on to list reasons why they believe these injustices are occurring. The first reason for injustice described is the lack of training and delay or failure to respond of police officers (Maze of Injustice, 41). If the police officers are not the first to respond the women lose confidence in pursuing a case against the perpetrators. The next reasons for injustice presented are issues within each level of the US's legal system. The lack of justice for Native women's sexual abuse within the tribal level is the lack of funding from the government. Also, the federal government limits the number of prison sentences tribal courts can make. The federal government also prohibits tribal courts to prosecute Non-Native suspects because of the 1978 Oliphant v. Suquamish case. On a federal level the issue of discrimination and limitations on prosecution of sexual assault is a reason for injustice. Things are a little more complicated on a States level. The distance of courts, language barriers, lack of funding for prosecution, and cultural competency are main causes of injustice for Native victims on a State level (Maze of Injustice 63-67).

The Amnesty International gives their audiences suggestions as to how to stop violence against Indigenous women. Some of their recommendations include: "Federal and state governments should take effective measures, in consultation and co-operation with Native American and Alaska Native peoples, to combat prejudice and eliminate stereotyping of and discrimination against Indigenous peoples. The federal government should take steps – including by providing sufficient funding – to ensure the full implementation of the 2005 reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act, particularly Title IX (Tribal Programs). Law enforcement agencies should recognize in policy and practice that all police officers have the authority to take action in response to reports of sexual violence, including rape, within their jurisdiction and to apprehend the alleged perpetrators in order to transfer them to the appropriate authorities for investigation and prosecution. In particular, where sexual violence is committed in Indian Country and in Alaska Native villages, tribal law enforcement officials must be recognized as having the authority to apprehend both Native and non-Native suspects. Federal authorities should ensure that tribal police forces have access to federal funding to enable them to recruit, train, equip and retain sufficient law enforcement officers to provide adequate law enforcement coverage which is responsive to the needs of the Indigenous peoples they serve." ( Maze of Injustice 84-87).

See also

- Custer's Revenge

- Faith Hedgepeth homicide

- INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence

- Indigenous feminism

- Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (Canada)

- Murder of Susan Poupart

- Native American feminism

- Squaw

- Sterilization of Native American women

- Rape in the United States

- Murder of Kathleen Jo Henry

References

- Gilpin, Lyndsey (June 7, 2016). "Native American women still have the highest rates of rape and assault". High Country News. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- "Ending Violence Against Native Women". Indian Law Resource Center. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- "Tribal Sovereignty". End Sexual Violence. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- World Health Organization., World report on violence and health (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002), Chapter 6, pp. 149.

- [Elements of Crimes, Article 7(1)(g)-6 Crimes against humanity of sexual violence, elements 1. Accessed through "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-05-06. Retrieved 2015-10-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)]

- McDougall (1998), para. 21

- McDougall (1998), para. 22

- "Frequently Asked Questions about the Change in the UCR Definition of Rape". Federal Bureau of Investigation. 11 December 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- Maze of Injustice: the failure to protect indigenous women from sexual violence in the USA (PDF). New York, NY: Amnesty International. 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

Sources

- The Facts on Violence Against Native American Women

- "Canada: Stolen Sisters," Amnesty International of Canada. 4 Oct. 2004. Accessed 30 Oct. 2005, PDF.

- Davis, Angela Y. Violence against Women and the Ongoing Challenge to Racism. New York: Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1985.

- Graef, Christine. "NCAI spearheads effort to stop violence against women." Indian Country Today. 29 Dec. 2003: A1.

- McDougall, Gay J. (1998). Contemporary forms of slavery: systematic rape, sexual slavery and slavery-like practices during armed conflict. Final report submitted by Ms. Jay J. McDougall, Special Rapporteur, E/CN.4/Sub.2/1998/13.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Andrea. "Not an Indian Tradition: The Sexual Colonization of Native Peoples." Hypatia 2003: 73.

- United States, Department of Justice. "American Indians and Crime." 30 Oct. 2005 PDF.

- "Using Alternative Healing Ways," Mending the Sacred Hoop Technical Assistance Project 2004. Accessed 30 Oct. 2005, PDF.

- "Maze of Injustice, The failure to protect Indigenous women from sexual violence in the USA", Amnesty International. 2007