Searching for Bobby Fischer

Searching for Bobby Fischer, released in the United Kingdom as Innocent Moves, is a 1993 American drama film written and directed by Steven Zaillian, in his directorial debut. Starring Max Pomeranc, Joe Mantegna, Joan Allen, Ben Kingsley and Laurence Fishburne, it is based on the life of prodigy chess player Joshua Waitzkin, played by Pomeranc, and adapted from the book of the same name by Joshua's father Fred.

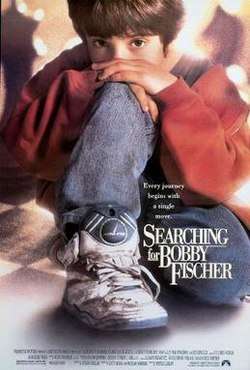

| Searching for Bobby Fischer | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Steven Zaillian |

| Produced by | William Horberg |

| Screenplay by | Steven Zaillian |

| Based on | Searching for Bobby Fischer: The Father of a Prodigy Observes the World of Chess by Fred Waitzkin |

| Starring | |

| Music by | James Horner |

| Cinematography | Conrad L. Hall |

| Edited by | Wayne Wahrman |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 110 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $12 million[1] |

| Box office | $7,266,383 |

Plot

Josh Waitzkin and his family discover that he possesses a gift for chess and they seek to nurture it. They hire a strict instructor, Bruce Pandolfini, who aims to teach the boy to be as aggressive as chess legend Bobby Fischer. The title of the film is a metaphor about the character's quest to adopt the ideal of Fischer and his determination to win at all costs. Josh is also heavily influenced by Vinnie, a speed chess hustler whom he meets in Washington Square Park. The two coaches differ greatly in their approaches to chess, and Pandolfini is upset that Josh continues to adopt the methods of Vinnie. The main conflict in the film arises when Josh refuses to accept Pandolfini's misanthropic frame of reference. Josh then goes on to win on his own terms.

Cast

- Max Pomeranc as Josh Waitzkin

- Joe Mantegna as Fred Waitzkin

- Joan Allen as Bonnie Waitzkin

- Ben Kingsley as Bruce Pandolfini

- Laurence Fishburne as Vinnie

- Michael Nirenberg as Jonathan Poe

- Robert Stephens as Poe's teacher

- David Paymer as Kalev

- Hal Scardino as Morgan Pehme

- Austin Pendleton as Asa Hoffmann

- Vasek Simek as Russian player

- William H. Macy as Tunafish father

- Dan Hedaya as Tournament director

- Laura Linney as Josh's school teacher

Some famous chess players have brief cameos in the film: Anjelina Belakovskaia, Joel Benjamin, Roman Dzindzichashvili, Kamran Shirazi, along with the real Joshua Waitzkin, Bruce Pandolfini, Vincent Livermore, and Russell Garber. Chess master Asa Hoffmann is played by Austin Pendleton; the real Hoffmann did not like the way he was portrayed. Chess expert Poe McClinton, still a park regular, is seen throughout the film. Pal Benko was supposed to be in the film but his part was cut out. Waitzkin's real mother and sister also have cameos.

The Russian player in the park (played by Vasek Simek) who holds up the sign "Game or Photograf Of Man Who Beet [sic] Tal 1953 • Five Dollars", was based on the real life of Israel Zilber.[2][3] Zilber, Latvian Chess Champion in 1958, defeated the teenage Mikhail Tal in 1952,[4] and during most of the 1980s was homeless and regarded as one of the top players in Washington Square Park.

Waitzkin's main chess foil character in the film, Jonathan Poe (played by Michael Nirenberg), is based on chess prodigy Jeff Sarwer. When Sarwer was asked what he felt about his portrayal in the film, he stated:

At the end of the day it was a Hollywood film, a work of fiction, and it helped popularize chess more so that's always a good thing. But I have a lot of distance to the actual book and film, the way I was portrayed was nothing at all like how I was in real life so what's the point in comparing myself to it?[5]

Sarwer versus Waitzkin match

At the end of the film in the final tournament, Josh is seen playing a tough opponent named Jonathan Poe. The character Jonathan Poe was not the actual name of Josh's opponent; his real name was Jeff Sarwer (a boy younger than Josh). In September 1985, Josh first played and was defeated by Jeff at the Manhattan Chess Club. In November of the same year, Josh returned to the Manhattan Chess Club and beat him in a rematch.[6] The film depicts their third match in the 1986 US Primary Championship. Near the end of the game, where Josh offers Poe a draw, Poe rejects the offer, the play continues and Poe loses. Sarwer rejected the draw offer in the real-world game as well, but the play continued to a draw due to bare kings. Under tournament tie-breaking rules, Waitzkin was determined to have played more challenging opponents during the overall competition and was awarded first place, but they were declared US Primary School co-champions.[7][8] Sarwer went on to win the 1986 World Championship Under-10 (Boys), with his sister Julia winning the World Championship Under-10 (Girls).

Poe versus Waitzkin endgame

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

The diagram depicts the game position in the film, with Waitzkin playing the black pieces, before Waitzkin offers Poe the draw. This position did not occur in the real Sarwer–Waitzkin game; it was contrived by Waitzkin and Pandolfini for the film. The following moves are executed:

- 1... gxf6 2. Bxf6 Rc6+ 3. Kf5 Rxf6+ 4. Nxf6 Bxf6 5. Kxf6 Nd7+ 6. Kf5 Nxe5 7. Kxe5??

In the October 1995 issue of Chess Life, Grandmaster Larry Evans stated that the position and sequence were unsound: Poe (playing White) could still have drawn the game by playing 7.h5 instead. Furthermore, the modern Lomonosov 7-piece endgame tablebase shows White has a win after 4. ... Bxf6, by placing Black in check, sacrificing White's rook for Black's bishop and queening safely.[9]

- 7... a5 8. h5 a4 9. h6 a3 10. h7 a2 11. h8=Q a1=Q+ 12. Kf5 Qxh8 0–1

White resigned.

Alternate endgame

An alternate endgame position had been composed by Pal Benko. It was supposed to have been used in the film, but was rejected on the day before the scene was filmed because it did not use the theme that Josh overused his queen.

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

In this position, Black should play:

- 1... Ne2

after which White is in zugzwang; he must play either 2.Bg3, losing the bishop to 2...Nxg3+, or 2.Bg1, allowing 2...Ng3#.[10]

Reception

The book and the film have each received positive reviews from critics. Waitzkin's book was praised by grandmaster Nigel Short,[11] as well as chess journalist Edward Winter, who called it "a delightful book" in which "the topics [are] treated with an acuity and grace that offer the reviewer something quotable on almost every page."[12] Screenwriter and playwright Tom Stoppard called the book "well written" and "captivating".[13]

The film currently has a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 42 reviews, with a weighted average of 8.13/10. The site's consensus reads: "As sensitive as the young man at its center, Searching for Bobby Fischer uses a prodigy's struggle to find personal balance as the background for a powerfully moving drama".[14] Roger Ebert gave the film a score of four stars (out of four), calling it "a film of remarkable sensitivity and insight", adding, "by the end of [the film], we have learned […] a great deal about human nature."[15] James Berardinelli gave the film three stars (out of four), calling it "an intensely fascinating movie capable of involving those who are ignorant about chess as well as those who love it."[16]

Bobby Fischer never saw the film and strongly complained that it was an invasion of his privacy by using his name without his permission. Fischer never received any compensation from the film, calling it "a monumental swindle".[17]

The film was nominated for Best Cinematography (Conrad L. Hall) at the 66th Academy Awards for 1993 but lost to Janusz Kaminski who won for Schindler's List. It won the category at the American Society of Cinematographers the same year. The film also ranked No. 96 in AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers.

References

- Eric G. Carter (1993). "1993–94 Film Releases".

- Wall, Bill. Searching For Bobby Fischer Trivia. Retrieved May 26, 2007.

- The Games of Israel Zilber Archived 2007-10-01 at the Wayback Machine Chessgames.com. Retrieved May 26, 2007.

- "Mikhail Tal vs. Josif Israel Zilber, LAT-ch (1952)". Chessgames.com.

- Shahade, Jennifer (8 January 2010). "The United States Chess Federation – Lost and Found: An Interview with Jeff Sarwer". United States Chess Federation. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- Wall, Bill ( August 7, 2007) Searching for Bobby Fischer (the movie) Trivia, Chess.com. Retrieved August 16, 2014

- pp. 214–22 of the book

- "Jeff Sarwer vs. Joshua Waitzkin, US Primary Championship (1986)". Chessgames.com. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- 5. Re2+ Kd1 6. Kxf6 Kxe2 7. h5 Nd7+ (a5? 8. Ke6 and White can win the pawn race safely) 8. Ke7 Ne5 9. h6 Ng6+ 10. Kf7 Ne5+ 11. Kg7 Nd7 12. h7 Nc5 and White queens

- Bruce Pandolfini, Endgame Workshop: Principles for the Practical Player, 2009, p. 64, Russell Enterprises, ISBN 978-1-888690-53-8

- The Spectator, April 8, 1989, pp. 30–31

- Searching for Bobby Fischer review, Edward Winter, Chess History, 1989

- The Observer, April 2, 1989, p. 45

- Searching for Bobby Fischer, Rotten Tomatoes

- Searching for Bobby Fischer review, Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times, August 11, 1993

- Searching for Bobby Fischer review, James Berardinelli, ReelViews, 1993

- Brady, Frank (2011). Endgame: Bobby Fischer's Remarkable Rise and Fall – from America's Brightest Prodigy to the Edge of Madness (1st ed.). Crown. pp. 267–68. ISBN 0-307-46390-7.

Further reading

- "20 years of Searching", Chess Life, August 2013, pp. 38–41

External links

- Searching for Bobby Fischer on IMDb

- Searching for Bobby Fischer at AllMovie

- Searching for Bobby Fischer at Box Office Mojo

- Updated article from 2006 by award-winning Esquire (UK) journalist Eamonn O'Neill