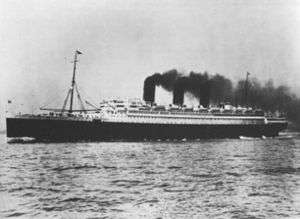

SS Paris (1916)

SS Paris was a French ocean liner built in Saint-Nazaire, France for the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique. The French Line's Paris was built by Chantiers de l'Atlantique of St. Nazaire. Although Paris was laid down in 1913, her launching was delayed until 1916, and she was not completed until 1921, due to World War I. When Paris was finally completed, she was the largest liner under the French flag, at 34,569 tons.[1]

SS Paris | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Paris |

| Namesake: | Paris, France |

| Owner: | French Line |

| Port of registry: | Le Havre, France |

| Ordered: | Compagnie Générale Transatlantique |

| Builder: | Penhoët, Saint Nazaire, France |

| Laid down: | 1913 |

| Launched: | 12 September 1916 |

| Maiden voyage: | 15 June 1921 |

| In service: | 15 June 1921 |

| Struck: | 1939 |

| Fate: | Caught fire, and capsized in Le Havre on 18 April 1939 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage: | 34,570 GRT |

| Length: | 764 ft (233 m) |

| Beam: | 85 ft (26 m) |

| Decks: | 10 |

| Speed: | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Capacity: |

|

Interior

Paris's interior reflected the transitional period of the early twenties, between the earlier preferred Jacobean, Tudor, Baroque, and Palladian themes in favor of the sleekness and simplicity of her Art Deco arrangements. Paris had something of a magic touch, with every possible kind of interior. Passengers could choose to travel in the standard conservative palatial cabins, but the ship also featured Art Nouveau and hints of the Art Deco that Ile de France would boast six years later.[2]

The luxury of Paris was something no other liner could claim to have. For starters, most first class staterooms had square windows rather than the usual round portholes. In a first class cabin, passengers were able to have a private telephone, which was extremely rare on board a ship. A valet on Paris could be summoned easily from his adjacent room, rather than in a cabin in the second class, uncomfortably far away.

Engines

The oil-fired turbine emerged during the twenties, replacing the pre-war coal system and allowing tidy, near polished perfection in the engine rooms. Finally, interested passengers who were very often gentlemen aboard could be invited below decks by the chief engineer for a tour of the machinery. The very core the ship's energy system impressed these onlookers, such as that on board Paris, where the 34,000-ton liner could be driven at 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) with over 2,500 people hardly feeling the effort. French ships quickly became known as the aristocrats of the ocean, and were very successful. Paris served in a partnership with her "running mate" ship France, making travel between the United States and France a legendary experience.

.jpg)

Life on board

Dining on Paris was excellent, her service was superb, and the living spaces were divinely comfortable and luxurious.[3] French Line ships had enormous appeal in the twenties-"Floating bits of France itself", as one brochure aptly stated. Service and accommodation were fine but the cuisine was its most outstanding feature, it is said that more sea gulls followed Paris than any other ship in hopes of grabbing scraps of the haute cuisine that were dumped overboard.[4] The French Line's success took off when a third ship joined the relay: SS Ile de France.

Operational history

On 15 October 1927 in New York Harbor she ran into the Norwegian Besseggen of Skien that was at anchor on the road. This collision resulted in the loss of six Norwegian lives. All blame was put on the officers of Paris. On 7 April 1929, Paris ran aground in New York Harbor; she was refloated 36 hours later.[5] On 18 April 1929, she ran aground again, this time on the Eddystone Rocks, Cornwall, United Kingdom. She was refloated two hours later, then anchored off Penlee, Cornwall, where 157 of her passengers were taken off by a tender and landed at Plymouth, Devon.[6] She was severely damaged by fire at Le Havre, Seine-Maritime, France, on 20 August 1929 and sank,[7] but was refloated on 11 September 1929, was repaired, and returned to service.

With the onset of the Great Depression late in 1929, even the French Line′s stylish ships were sailing only a third full. The French Line avoided the possibility of laying them up by pressing them into cruise work. To some, it seemed scandalous to have such ships lazily roaming the Mediterranean or Scandinavia as cruise ships with a mere 300 passengers on board.

Loss

On 18 April 1939, Paris caught fire while docked in Le Havre and temporarily blocked the new superliner Normandie from exiting dry dock. She capsized and sank in her berth where she remained until after World War II, almost a decade later. A year after the war had ended, the 50,000-ton German liner Europa was handed over to the French Line as compensation for Normandie and renamed Liberté. While Liberté was being refitted in Le Havre, a December gale tore the ship from her moorings and threw her into the half-submerged wreck of Paris. She settled quickly, but in an upright position. Six months later Liberté was refloated and by spring 1947 she was in St. Nazaire for her final rebuilding. The wreck of Paris remained on the spot until 1947, when she finally was scrapped on site.[8]

Paris was one of the nearly a dozen French ships destroyed by fire during the 1930s and 1940s.

References

- "Great ships". Archived from the original on 15 April 2007. Retrieved 18 May 2007.

- Designing Liners: A History of Interior Design Afloat by Anne Massey

- "The French Line". Archived from the original on 4 January 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2007.

- Great Luxury Liners 1927-1954, A Photographic Record by William H. Miller, Jr.

- "Mishap to Atlantic liner". The Times (45171). London. 8 April 1929. col F, p. 11.

- "French liner on rocks". The Times (45181). London. 19 April 1929. col C, p. 18.

- "Casualty reports". The Times (45287). London. 21 August 1929. col C, p. 20.

- "The Great Ocean Liners". Retrieved 18 May 2007.