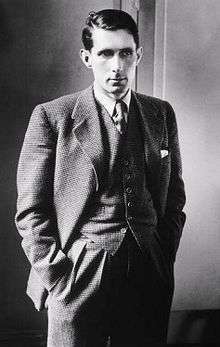

Roland Penrose

Sir Roland Algernon Penrose CBE (14 October 1900 – 23 April 1984) was an English artist, historian and poet. He was a major promoter and collector of modern art and an associate of the surrealists in the United Kingdom.[1] During the Second World War he put his artistic skills to practical use as a teacher of camouflage.

Roland Penrose | |

|---|---|

Roland Penrose | |

| Born | October 14, 1900 London, United Kingdom |

| Died | April 23, 1984 (aged 83) Chiddingly, East Sussex, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Architecture |

| Known for | Home Guard Manual of Camouflage Institute of Contemporary Arts |

| Movement | Surrealism |

| Spouse(s) | |

Penrose married the poet Valentine Boué and then the photographer Lee Miller.

Biography

Early life

Penrose was the son of James Doyle Penrose (1862–1932),[2] a successful portrait painter, and Elizabeth Josephine Peckover, the daughter of Baron Peckover, a wealthy Quaker banker. He was the third of four brothers; his older brother was the medical geneticist Lionel Penrose.[3]

Roland grew up in a strict Quaker family in Watford and attended the Downs School, Colwall, Herefordshire, and then Leighton Park School, Reading, Berkshire. In August 1918, as a conscientious objector, he joined the Friends' Ambulance Unit, serving from September 1918 with the British Red Cross in Italy. After studying architecture at Queens' College, Cambridge, Penrose switched to painting and moved to France, where he lived from 1922 and where in 1925 he married his first wife the poet Valentine Boué.[4]

During this period he became friends with Pablo Picasso, Wolfgang Paalen and Max Ernst, who would have the strongest influence on his work and most of the leading Surrealists.

Surrealism

Penrose returned to London in 1936 and was one of the organisers of the London International Surrealist Exhibition, which led to the establishment of the English surrealist movement. Penrose settled in Hampstead, north London,[5] where he was the centre of the community of avant-garde British artists and emigres who had settled there. He opened the London Gallery on Cork Street, where he promoted the Surrealists as well as the sculptor Henry Moore, to whom he was first introduced by his close friend Wolfgang Paalen, as well as the painter Ben Nicholson, and the sculptors Barbara Hepworth and Naum Gabo.

Penrose commissioned a sculpture from Moore for his Hampstead house that became the focus of a press campaign against abstract art. Penrose and Boué's marriage had broken down in 1934 and they divorced in 1937. Penrose came to Cornwall, in June 1937, staying in his brother's home at Lambe Creek on the Truro River. He was accompanied by a group of surrealist artists; his new lover Leonora Carrington, Max Ernst, Eileen Agar, Lee Miller, Man Ray, Edouard Mesens, Paul Eluard, and Joseph Bard. Photographs of their stay can be seen at Falmouth Art Gallery.[6]

In 1938, Penrose organised a tour of Picasso's Guernica that raised funds for the Republican Government in Spain. In the same year he had an affair with Peggy Guggenheim, when she met him at her gallery Guggenheim Jeune to try and sell him a painting by French Surrealist artist Yves Tanguy. Penrose told Guggenheim that he loved an American woman in Egypt and in her autobiography Guggenheim reports she told him to "go to Egypt to get his ladylove."[7] By 1939 Penrose had begun his relationship with the model and photographer Lee Miller; they finally married in 1947. They lived at 21 Downshire Hill, Hampstead, London, which now bears a blue plaque.[8]

Penrose remained close to his first wife. They met again in London during the war, and Valentine came to live with Roland and Lee Miller for eighteen months. Valentine died in Penrose's house in East Sussex 1978.[4]

World War II camouflage work

As a Quaker, Penrose had been a pacifist, but after the outbreak of World War II he volunteered as an air raid warden and then taught military camouflage at the Home Guard training centre at Osterley Park.[9][10] This led to Penrose's commission as a captain in the Royal Engineers.

He worked as senior lecturer at the Eastern Command Camouflage School in Norwich, and at the Camouflage Development and Training Centre at Farnham Castle, Surrey. During his lectures, he used to startle his audiences by inserting a colour photograph of his partner Lee Miller, lying on a lawn naked but for a camouflage net; when challenged, he argued "if camouflage can hide Lee's charms, it can hide anything".[11] Forbes suggests this was a surrealist technique being put into service.[11] His lectures were respected by both trainees and colleagues.[12] In 1941 Penrose wrote the Home Guard Manual of Camouflage, which provided accurate guidance on the use of texture, not only colour, especially for protection from aerial photography (monochrome at that time).[12]

Penrose applied for a job at the Foreign Office, but was turned down because of a perceived security risk, possibly relating to the investigation of Lee Miller by MI5.[13]

The ICA

After the war, Penrose co-founded the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London, with the art critic and writer Herbert Read in 1947. Penrose organised the first two ICA exhibitions: 40 Years of Modern Art, which included many key works of Cubism, and 40,000 Years of Modern Art, which reflected his interest in African sculpture. Penrose was a presence at the ICA for 30 years; he produced a number of books, which cover the works of his friends Pablo Picasso, Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Man Ray and Antoni Tàpies. He was also a trustee of the Tate Gallery; he organised a survey of Picasso's work there in 1960 and used his contacts to negotiate purchases of works by Picasso and the Surrealists at discounted prices.

Farley Farm

Penrose and Miller bought Farley Farm House in Sussex in 1949, where he displayed his valuable collection of modern art and in particular the Surrealists and works by Picasso. Penrose also designed the landscaping around the house as a setting for works of modern sculpture. In 1972, thieves broke into his London flat, stole a number of works, and then demanded a ransom. During a BBC TV interview, Penrose stated he would refuse all demands for a ransom.

The paintings were later recovered as a result of diligent police work. Some were damaged but were restored by the Tate Gallery. After the death of his wife, Penrose loaned several key paintings from her collection to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh, a practice that Penrose's descendants have continued with his collection.

Penrose's former home at Farley Farm House – now owned by his son, Antony Penrose – is now a museum and an archive which is open to the public for guided tours on pre-determined days.

Legacy

His bold and enigmatic surrealist paintings, drawings and objects are some of the most enduring images of the movement. He is remembered for his postcard collages, examples of which are found in major national collections across Britain. He was awarded the CBE in 1960,[14] and he was knighted for his services to the visual arts in 1966.[15] The University of Sussex awarded him an honorary Doctorate of Letters in 1980.

Penrose is the uncle of the physicist and polymath Sir Roger Penrose. He and Lee Miller had a son, Antony Penrose, who continues to run Farley Farm House as a museum and archive.[16]

Audio recording

An interview with Roland Penrose (and Lee Miller) recorded in 1946 can be heard on the audio CD Surrealism Reviewed.

Film recording

A filmed interview between Roland Penrose and Antoni Tàpies was directed by James Scott in Spain in 1974. The film, not previously completed, is in pre-production in 2018. The footage is available for viewing through the Fundació Antoni Tàpies.

See also

Notes

- About Roland Penrose.

- "James Doyle Penrose | artnet". www.artnet.com. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Cork, Richard (May 2006). "Penrose, Sir Roland Algernon (1900–1984)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004, online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31538. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- Kellaway, Kate (22 August 2010). "Tony Penrose: 'With Picasso, the rule book was torn up'". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher, eds. (1993). The London Encyclopaedia (Rev. ed.). London: PaperMac. p. 243. ISBN 0333576888. OCLC 28963301.

- Breton, Andrea (2017). "A brief and incomplete history of art and artists in Cornwall". Best of Cornwall 2017. pp. 23–32.

- Guggenheim, Peggy (2005). Out of this Century: Confessions of an Art Addict. London: Andre Deutsch. pp. 191–193. ISBN 9780233001388.

- Clark, Ross (9 July 2003). "Daily Telegraph report on installation of blue plaque, 2003". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- Newark, 2007.

- "Surrealist who tried to paint a whole nation green". The Scotsman. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- Forbes, 2009, page 151.

- Forbes, 2009, pages 151–152.

- Gardham, Duncan (3 March 2009). "MI5 investigated Vogue photographer Lee Miller on suspicion of spying for Russians, files show". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- "No. 42231". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 1960. p. 8898.

- "No. 43921". The London Gazette. 11 March 1966. p. 2703.

- Penrose, Anthony (8 April 2010). "Roland Penrose and Lee Miller at Farley Farm". Colchester Decorative and Fine Arts Society. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

References

- Forbes, Peter. Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage. Yale, 2009.

- Newark, Tim. Now you see it… Now You Don't. History Today, March 2007.

- Penrose, Roland. Home Guard Manual of Camouflage. George Routledge and Sons, 1941.

Further reading

ODNB article by Richard Cork, 'Penrose, Sir Roland Algernon (1900–1984)', rev. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2006 accessed 27 May 2009

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roland Penrose. |