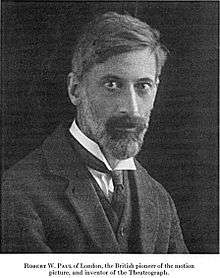

Robert W. Paul

Robert William Paul (3 October 1869 – 28 March 1943) was an English pioneer of film and scientific instrument maker.

Robert W. Paul | |

|---|---|

Paul c. 1896 | |

| Born | Robert William Paul 3 October 1869 Liverpool Road, London, England |

| Died | 28 March 1943 (aged 73) Putney, London, England |

| Occupation | Electrician |

| Known for | The theatrograph |

He made narrative films as early as April 1895. Those films were shown first in Edison Kinescope knockoffs. In 1896 he showed them projected. That was about the time the Lumière brothers were pioneering projected films in France.[1]

His first notably successful scientic device was his Unipivot galvanometer.[2]

In 1999 the British film industry erected a commemorative plaque on his building at 44 Hatton Garden, London.

Early career

Paul was born in Liverpool Road, in present-day Inner London, and began his technical career learning instrument-making skills at the Elliott Brothers, a firm of London instrument makers founded in 1804, followed by the Bell Telephone Company in Antwerp. In 1891, he established an instrument-making company, Robert W. Paul Instrument Company, initially with a workshop at 44 Hatton Garden, London, later his office.

In 1894, he was approached by two Greek businessmen who wanted him to make copies of an Edison Kinetoscope that they had purchased. He at first refused, then found that Edison had not patented the invention in Britain. Subsequently, Paul himself would go on to purchase a Kinetoscope, intent on taking it apart and re-creating an English-based version. He manufactured a number of these - according to one account of his "200" but later revised this to "60".

However, the only films available were 'bootleg' copies of those produced for the Edison machines. As Edison had patented his camera (the details of which were a closely guarded secret), Paul resolved to solve this bottleneck by creating his own camera. Via a mutual friend, Henry W. Short, Paul was introduced to Birt Acres, a photographic expert and much-respected photographer who was the General Manager at Elliott & Son's photographic works. Acres had been working on a machine for rapid photographic printing and Paul applied some of this mechanism to the camera. This camera, dubbed the Paul-Acres Camera by historian John Barnes,[3] was invented in March 1895, would be the first camera made in England to the "Edison" 35mm film format.

On October 24, 1895, Paul applied for a patent for a device to evoke the effects that H. G. Wells had described in his novel The Time Machine, published the previous year. Audiences would be given the illusion of traveling backwards or forwards in time, of seeing in close-up or at a distance life in eras long before or after their own times.[4] Paul wrote, "The Spectators should be given the sensation of voyaging from the last epoch to the present, or the present epoch may be supposed to have been accidentally passed and a present scene represented on the machine coming to a standstill, after which the impression of travelling forward again to the present epoch may be given, and the re-arrival notified by the representation on the screen of the place at which the exhibition is held ..."[5] The patent was never completed and nothing came of it.[6]

Film innovation

Paul obtained a concession to operate a kinetoscope parlour at the Earls Court Exhibition Centre, and the success of this inspired him to contemplate the possibilities of projecting a moving image on to a screen, something that Edison had never considered. And while Paul and Birt Acres would share innovator status for creating Britain's first 35mm camera, soon after conception both men would dissolve the partnership and become competitors in the film camera and projector markets. [7]

Acres would present his projector at the Royal Photographic Society on 14 January 1896 to much acclaim. Paul would present his own, the Theatrograph, shortly after on 20 February at Finsbury Park College. Ironically this is exactly the same day the Lumieres' films would first be projected in London.[8]

In 1896, he pioneered in the UK a system of projecting motion pictures onto a screen, using a double Maltese cross system. This coincided with the advent of the projection system devised by the Lumiere Brothers. After some demonstrations before scientific groups, he was asked to supply a projector and staff to the Alhambra Music Hall in Leicester Square, and he presented his first theatrical programme on 25 March 1896. This included films shot by Birt Acres featuring cartoonist Tom Merry drawing caricatures of the German Emperor Kaiser Wilhelm II (1895),[9] and Prince Bismarck (1895).[10] Merry had previously performed his lightning-fast drawing as part of a music hall stage act. (The Lumieres were appearing on the bill at the Empire Music Hall, nearby.) The use of his 'Theatrograph' in music halls up and down the country helped popularise early cinema in Britain. There were many showmen who wished to imitate Paul's success, and some of these wanted to make their own films of 'local interest'. It was necessary to set up a completely separate manufacturing department producing cameras, projectors, and cinema equipment, with its own office and showroom.[11]

Paul would also continue his innovations in the portable camera field. His 'Cinematograph Camera No. 1', built in April 1896, would be the first camera to feature reverse-cranking. This mechanism allowed for the same film footage to be exposed several times. The ability to create super-positions and multiple exposures would be of great significance. This technique was used in Paul's 1901 film Scrooge, or, Marley's Ghost, the oldest known film adaptation of Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol. It is noted that the first camera that George Melies would use was built by R.W. Paul.[8]

In 1898 he designed and constructed Britain's first film studio in Muswell Hill, north London.

The British Film Catalogue credits Paul's Our New General Servant (1898) with the "first use of intertitles".[12]

Extended career

In the meantime, he continued with his original business, focusing on his internationally renowned Unipivot galvanometer. Paul's instruments were internationally renowned: he won gold medals at the St Louis Exposition in 1904 and the Brussels Exhibition in 1910, among others.[13] Upon the outbreak of World War I, he began producing military instruments including early wireless telegraphy sets, and instruments for submarine warfare. In December 1919, the Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company took over the smaller but successful Robert W. Paul Instrument Company and became The Cambridge and Paul Instrument Company Ltd. The name was shortened to the Cambridge Instrument Co Ltd in 1924 when it was converted to a public company.[14]

Paul continued to make his own films, selling them either directly or through the new distribution companies that were springing up. He was a very innovative director and cameraman, pioneering techniques such as the close up and cutting from one scene to another. However, his growing business interests crowded out film, and he moved out of the infant industry as early as 1910. Nevertheless, his importance was always recognized by contemporaries, who often referred to him as 'Daddy Paul'.[15]

Coincidentally and without prior knowledge of the above, in 1994 a technology company called Kinetic took over the building at 44 Hatton Garden and renamed it Kinetic House.[16] In 1999, the British film industry commemorated the work of Paul by erecting a commemorative plaque on the building attended by members of the film industry and unions including Sir Sydney Samuelson.[17]

Selected filmography

Filmed by Birt Acres:

- The Derby (1895)

- Footpads (1895)

- The Oxford and Cambridge University Boat Race (1895)

- Rough Sea at Dover (1895)

Made independently:

- Blackfriars Bridge (1896)

- Comic Costume Race (1896)

- A Sea Cave Near Lisbon (1896)

- The Soldier's Courtship (1896)

- The Twins' Tea Party (1896)

- Two A.M.; or, the Husband's Return (1896)

- Robbery (1897)

- Come Along, Do! (1898)

- A Switchback Railway (1898)

- Tommy Atkins in the Park (1898)

- Our New General Servant (1898)

- The Miser's Doom (1899)

- Upside Down; or, the Human Flies (1899)

- Army Life; or, How Soldiers Are Made (1900)

- Chinese Magic (1900)

- Krugers Dream of an Empire (1900)

- Hindoo Jugglers (1900)

- A Railway Collision (1900)

- Artistic Creation (1901)

- Cheese Mites; or, Lilliputians in a London Restaurant (1901)

- The Countryman and the Cinematograph (1901)

- The Devil in the Studio (1901)

- The Haunted Curiosity Shop (1901)

- The Magic Sword (1901)

- An Over-Incubated Baby (1901)

- Scrooge, or, Marley's Ghost (1901)

- Undressing Extraordinary (1901)

- The Waif and the Wizard (1901)

- The Extraordinary Waiter (1902)

- A Chess Dispute (1903)

- Extraordinary Cab Accident (1903)

- The Voyage of the Arctic (1903)

- The Unfortunate Policeman (1905)

- The '?' Motorist (1906)

- Is Spiritualism A Fraud? (1906)

Legacy

In April 2019, the Bruce Castle Museum held a 150th anniversary exhibition curated by Ian Christie entitled 'Animatograph! How cinema was born in Haringey'.[18]

In August 2019, Barnet Council approved The Light House scheme by architects Lipton Plant Architects at the corner of Sydney Road and Colney Hatch Lane, Muswell Hill, featuring an unusual ‘shimmering void’ as a tribute to Paul.[19]

In November 2019, the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford opened an exhibition, The Forgotten Showman: How Robert Paul Invented British Cinema, dedicated to Paul and his work in the film industry.[20]

References

- https://thebioscope.net/2011/07/25/the-soldiers-courtship/, retrieved 4/8/20

- https://physicsmuseum.uq.edu.au/unipivot-galvanometer, retrieved April 8, 2020

- 1920-2008, Barnes, John (1996–1998). The beginnings of the cinema in England 1894-1901. Maltby, Richard, 1952-. Exeter [England]: University of Exeter Press. ISBN 0859895645. OCLC 36996858.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Baxter, John (1970). Science Fiction in the Cinema. New York, N.Y.: Paperback Library. pp. 14. ISBN 9780498074165.

- Cook, Olive (1965). The Saturday Book Vol.25. London: Hutchinson & Company.

- https://www.victorian-cinema.net/paul , retrieved April 8, 2020

- Mast, Gerald; Kawin, Bruce F. (2007). "Birth". In Costanzo, William (ed.). A Short History of the Movies (Abridged 9th ed.). Pearson Education, inc. pp. 23–24. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16.

- However this distinction has also been claimed by Louis Aimé Augustin Le Prince (28 August 1841 – vanished 16 September 1890) who was a French inventor and shot the first moving pictures on paper film using a single lens camera.[1][2] He has been heralded as the "Father of Cinematography" since 1930.[3] Mast, Gerald; Kawin, Bruce F. (2007). "Birth". In Costanzo, William (ed.). A Short History of the Movies (Abridged 9th ed.). Pearson Education, inc. pp. 23–24. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16.

- Tom Merry Lightning Cartoonist, sketching Kaiser Wilhelm II, Birt Acres (1895) (BFI) accessed 3 Nov 2007

- Tom Merry Lightning Cartoonist, sketching Bismarck, Birt Acres (1895) (BFI) accessed 3 Nov 2007

- London on Film (Screening Spaces), Pam Hirsch (Editor), Chris O'Rourke (Editor) Palgrave Macmillan; 1st ed. 2017 edition (October 28, 2017) Language: English ISBN 978-3319649788

- The British Film Catalogue, by Denis Gifford, Routledge 2016, p 142

- https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8413455/unipivot-galvanometer-galvanometer, retrieved 4/8/20

- http://waywiser.fas.harvard.edu/people/2462/robert-w-paul-instrument-company, retrieved A[pril 8, 2020

- Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema (Cinema and Modernity), Ian Christie, University of Chicago Press; First edition (December 9, 2019) Language: English ISBN 978-0226105628

- https://www.buildington.co.uk/london-ec1/44-hatton-garden/kinetic-house/id/6628, retrieved April 8, 2020

- https://www.londonremembers.com/memorials/robert-w-paul, retrieved Ap[ril 8 2020

- "Animatograph! How cinema was born in Haringey". Harringay Online. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- Waite, Richard (27 August 2019). "Lipton Plant gets OK for scheme with cutaway honouring British film pioneer". Architects' Journal. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- Blow, John (22 November 2019). "Bradford's National Media Museum's new exhibition on 'ignored' cinema pioneer Robert Paul begins". The Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert W. Paul. |

- Robert W. Paul on IMDb

- Robert William Paul (Who's Who of Victorian Cinema)