Rhabdodontidae

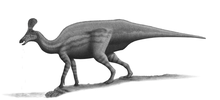

Rhabdodontidae is a family of herbivorous ornithopod dinosaurs whose earliest stem members appeared in the middle of the Lower Cretaceous. The oldest dated fossils of these stem members were found in the Barremian Castrillo de la Reina Formation of Spain, dating to approximately 129.4 to 125.0 million years ago.[1] With their deep skulls and jaws, Rhabdodontids were similar to large, robust iguanodonts. The family was first proposed by David B. Weishampel and colleagues in 2003.[2] Rhabdodontid fossils have been mainly found in Europe in formations dating to the Late Cretaceous.

| Rhabdodontids | |

|---|---|

| |

| Rhabdodon priscus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Suborder: | †Ornithopoda |

| Clade: | †Rhabdodontomorpha |

| Family: | †Rhabdodontidae Weishampel, 2003 |

| Genera | |

The defining characteristics of the clade Rhabdodontidae include the spade-shape of the teeth, the presence of three or more premaxillary teeth, the distinct difference between the two maxillary and dentary teeth ridge patterns, and the uniquely shaped femur, humerus, and ulna.[1] Members of Rhabdodontidae have an adult body length of 1.6 to 6.0 meters.[3]

Description

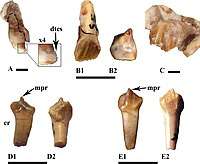

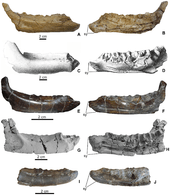

Teeth

Rhabdodontids have a simple dentition with leaf-shaped teeth used for a powerful scissors-like shearing. These teeth are well-suited to a diet of tough and fibrous plants.[4] Each tooth has a ridge on it that is offset from the midline of the tooth. These ridges also have a specific pattern which is unique to Rhabodontids: their dentary teeth have a central primary ridge with multiple equally spaced secondary ridges, and their maxillary teeth have no primary ridge and have similarly-sized secondary ridges.[1][3][4]

.jpeg)

Postcranium

Unique characteristics are found in the femur, the humerus, and the ulna bones. The femur has a non-pendant, crested fourth trochanter.[1] The humerus lacks a proximal bicipital sulcus, and a concave border between the head and the deltopectoral crest.[1] The ulna has a large olecranon process.[1]

Classification

There are differing opinions as to the constituents of Rhabdodontidae. Originally they were defined as the last common ancestor of Zalmoxes robustus and Rhabdodon priscus.[2] Later, Paul Sereno proposed a new definition, the most inclusive clade containing Rhabdodon priscus but not Parasaurolophus walkeri.[5] More recently, a morphological diagnosis was proposed, that excluded Muttaburrasaurus, unlike Sereno's definition. The clade Rhabdodontomorpha was coined to contain the larger group.[1] The following cladogram was recovered by Dieudonné and colleagues in 2016:[1]

| Iguanodontia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Evolution

Rhabdodontids first appeared during the Barremian stage of the Early Cretaceous, and an extensive fossil record shows that they remained extant until the Maastrichtian stage at the end of the Late Cretaceous. During much of the Late Cretaceous, an isolated island habit in the western Tethyan archipelago contributed to the evolution of rhabdodontids in two main ways. First, the rhabdodontid dentition is relatively primitive, which is consistent with their habitat being sheltered from expansive mixing leading to a long period of dominance.[6] Second, the fossil record contains three genera of rhabdodontids – Mocholdon, Zalmoxes, and Rhabdodon – that make up two geographically separated lines in the archipelago.

Traditionally, it has been thought Mochlodon and Zalmoxes were insular dwarfs. The smaller sizes of Mocholodon (1.6 to 1.8 m) and Zalmoxes (2.0 to 2.5 m) relative to Rhabodon (5.0 to 6.0 m)[6] and the island locale that all three genera shared led to the hypothesis of island nanism in the case of the former two. However, Ősi et al. (2012) proposed that Rhabdodon underwent gigantism on the mainland, as opposed to Zalmoxes and Mochlodon experiencing nanism on island habitats.[3] Ösi and colleagues used femur length to estimate body size through evolution in the rhabdodontid lineage. The conclusion was that in the eastern lineage comprising Zalmoxes and Mochlodon, the size ranges of both were too close to that of the ancestral rhabdodontid to support the hypothesis of nanism. Ösi and colleagues instead came to the conclusion that Rhabdodon in the western lineage is a case of gigantism in the group Rhabdodontidae.[3]

Relationship to other fauna

Rhabdodontids and Nodosaurids were overtaken by Hadrosaurids as the dominating herbivorous dinosaur group during the Maastrichtian period, 72.1–66.0 million years ago, of the Late Cretaceous. Titanosaurs coexisted with all of these groups throughout the Maastrichtian. Transylvania is the only location known thus far to have had Rhabdodontids, Nodosaurids, Titanosaurs, and Hadrosaurids all coexisting together.[6]

Paleobiology

The Late Cretaceous is characterized by a warm temperate climate that extended to the poles, elevated sea levels, and inland seas. With a dentition adapted to shearing vegetation, members of the family Rhabododontidae were well-suited for life in the lush, vegetative environment at middle latitudes.

References

- Dieudonné; et al. (2016). "An Unexpected Early Rhabdodontid from Europe (Lower Cretaceous of Salas de los Infantes, Burgos Province, Spain) and a Re-Examination of Basal Iguanodontian Relationships". PLoS ONE. 11 (6): e0156251. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1156251D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0156251. PMC 4917257. PMID 27333279.

- Weishampel, D.B.; Jianu, C.-M.; Csiki, Z.; Norman, D.B. (2003). "Osteology and phylogeny of Zalmoxes (n. g.), an unusual euornithopod dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Romania". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 1 (2): 65_123. doi:10.1017/S1477201903001032.

- Ősi, A.; Prondvai, E.; Butler, R.; Weishampel, D. B. (2012). Evans, Alistair Robert (ed.). "Phylogeny, Histology and Inferred Body Size Evolution in a New Rhabdodontid Dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Hungary". PLoS ONE. 7 (9): e44318. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...744318O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044318. PMC 3448614. PMID 23028518.

- Godefroit, Pascal; Garcia, Géraldine; Gomez, Bernard; Stein, Koen; Cincotta, Aude; Lefèvre, Ulysse; Valentin, Xavier (2017-10-26). "Extreme tooth enlargement in a new Late Cretaceous rhabdodontid dinosaur from Southern France". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 13098. Bibcode:2017NatSR...713098G. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-13160-2. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5658417. PMID 29074952.

- Sereno, P.C. (2005). "Stem Archosauria Version 1.0." TaxonSearch. Available: http://www.taxonsearch.org/Archive/stem-archosauria-1.0.php Archived 2009-01-15 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 24 November 2010.

- Csiki-Sava, Zoltán; Buffetaut, Eric; Ősi, Attila; Pereda-Suberbiola, Xabier; Brusatte, Stephen L. (2015-01-08). "Island life in the Cretaceous - faunal composition, biogeography, evolution, and extinction of land-living vertebrates on the Late Cretaceous European archipelago". ZooKeys (469): 1–161. doi:10.3897/zookeys.469.8439. ISSN 1313-2989. PMC 4296572. PMID 25610343.

.jpg)