Rabatak inscription

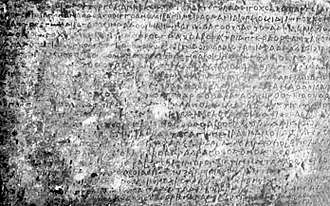

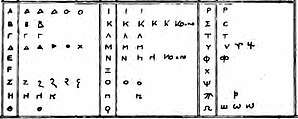

The Rabatak inscription is an inscription written on a rock in the Bactrian language and the Greek script, which was found in 1993 at the site of Rabatak, near Surkh Kotal in Afghanistan. The inscription relates to the rule of the Kushan emperor Kanishka, and gives remarkable clues on the genealogy of the Kushan dynasty. It dates to the 2nd century CE.

| Rabatak inscription | |

|---|---|

The Rabatak inscription. | |

| Period/culture | 2nd century CE |

| Discovered | 36.149434°N 68.404101°E |

| Place | Rabatak, Afghanistan |

| Present location | Kabul Museum, Kabul, Afghanistan |

Rabatak  Rabatak | |

Discovery

The Rabatak inscription was found near the top of an artificial hill, a Kushan site, near the main Kabul-Mazar highway, to the southeast of the Rabatak pass which is currently the border between Baghlan and Samangan provinces. It was found by Afghan mujahideen digging a trench at the top of the site, along with several other stone sculptural elements such as the paws of a giant stone lion, which have since disappeared.

An English aid worker who belonged to the demining organization HALO Trust, witnessed and took a photograph of the inscription, before reporting the discovery. This photograph was sent to the British Museum, where its significance, as an official document that named four of the Kushan kings, was recognised by Joe Cribb. He determined that it was similar to a famous inscription found in the 1950s at Surkh Kotal, by the Delegation Archeologique Francaise en Afghanistan. Cribb shared the photograph with one of only a handful of living people able to read the Bactrian language, Nicholas Sims-Williams of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). More photographs arrived from HALO Trust workers, and a first translation was published by Cribb and Sims-Williams in 1996.

| English translation | Transliteration | Original (Greco-Bactrian script) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Because of the civil war in Afghanistan years passed before further examination could be accomplished. In April 2000 the English historian Dr. Jonathan Lee, a specialist on Afghan history, travelled with Robert Kluijver, the director of the Society for the Preservation of Afghanistan's Cultural Heritage, from Mazar-i Sharif to Pul-i Khumri, the provincial capital of Baghlan, to locate the stone. It was eventually found in a store at the Department of Mines and Industry. Dr. Lee took photographs which allowed Prof. Sims-Williams to publish a more accurate translation, which was followed by another translation once Professor Sims-Williams had examined the stone in person (2008).

In July 2000 Robert Kluijver travelled with a delegation of the Kabul Museum to Pul-i Khumri to retrieve the stone inscription (weighing between 500 and 600 kilograms). It was brought by car to Mazar-i Sharif and flown from there to Kabul. At the time the Taliban had a favorable policy toward the preservation of Afghan cultural heritage, including pre-Islamic heritage. The inscription, whose historical value had meanwhile been determined by Prof. Sims-Williams, became the centrepiece of the exhibition of the (few) remaining artifacts in the Kabul Museum, leading to a short-lived inauguration of the museum on 17 August 2000. Senior Taliban objected to the display of pre-Islamic heritage, which led to the closing of the museum (and the transfer of the Rabatak inscription to safety), a reversal of the cultural heritage policy and eventually the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamyan and other pre-Islamic statuary (from February 2001 onwards).

Today the Rabatak inscription is again on display in the reopened Afghan National Museum or Kabul Museum.

The Rabatak site, again visited by Robert Kluijver in March 2002, has been looted and destroyed (the looting was performed with bulldozers), reportedly by the local commander at Rabatak.

Main findings

Religion

The first lines of the inscription describe Kanishka as:

- "the great salvation, the righteous, just autocrat, worthy of divine worship, who has obtained the kingship from Nana and from all the gods, who has inaugurated the year one as the gods pleased" (Trans. Professor Sims-Williams)

The "Arya language"

Follows a statement regarding the writing of the inscription itself, indicating that the language used by Kanishka in his inscription was self-described as the "Aryan language".

Regnal eras

Also, Kanishka announces the beginning of a new era starting with the year 1 of his reign, abandoning the therefore "Great Arya Era" which had been in use, possibly meaning the Vikrama era of 58 BCE.

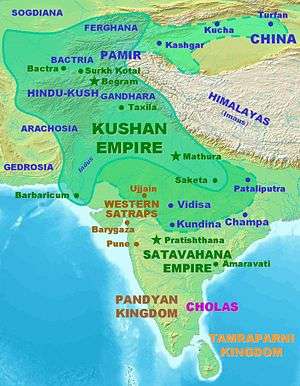

Territorial extent

Lines 4 to 7 describe the cities which were under the rule of Kanishka, among which four names are identifiable: Saketa, Kausambi, Pataliputra, and Champa (although the text is not clear whether Champa was a possession of Kanishka or just beyond it). The Rabatak inscription is significant in suggesting the actual extent of Kushan rule under Kanishka, which would go significantly beyond traditionally held boundaries:[1]

Succession

Finally, Kanishka makes the list of the kings who ruled up to his time: Kujula Kadphises as his great-grandfather, Vima Taktu as his grandfather, Vima Kadphises as his father, and himself Kanishka:

- "for King Kujula Kadphises (his) great grandfather, and for King Vima Taktu (his) grandfather, and for King Vima Kadphises (his) father, and *also for himself, King Kanishka" (Cribb and Sims-Williams 1995/6: 80)

Another translation by Prof. B.N. Mukherjee has been given much currency, but it lacks the accuracy and authority of Sims-Williams' translation.

Mukherjee translation

B. N. Mukherjee also published a translation of the inscription.[2][3]

- 1–3

- "The year one of Kanishka, the great deliverer, the righteous, the just, the autocrat, the god, worthy of worship, who has obtained the kingship from Nana and from all the gods, who has laid down (i.e. established) the year one as the gods pleased."

- 3–4

- "And it was he who laid out (i.e. discontinued the use of) the Ionian speech and then placed the Arya (or Aryan) speech (i.e. replaced the use of Greek by the Aryan or Bactrian language)."

- 4–6

- "In the year one, it has been proclaimed unto India, unto the whole realm of the governing class including Koonadeano (Kaundinya< Kundina) and the city of Ozeno (Ozene, Ujjain) and the city of Zageda (Saketa) and the city of Kozambo (Kausambi) and the city of Palabotro (Pataliputra) and so long unto (i.e. as far as) the city of Ziri-tambo (Sri-Champa)."

- 6–7

- "Whichever rulers and the great householders there might have been, they submitted to the will of the king and all India submitted to the will of the king."

- 7–9

- "The king Kanishka commanded Shapara (Shaphar), the master of the city, to make the Nana Sanctuary, which is called (i.e. known for having the availability of) external water (or water on the exterior or surface of the ground), in the plain of Kaeypa, for these deities – of whom are Ziri (Sri) Pharo (Farrah) and Omma."

- 9-9A

- "To lead are the Lady Nana and the Lady Omma, Ahura Mazda, Mazdooana, Srosharda, who is called ... and Komaro (Kumara) and called Maaseno (Mahasena) and called Bizago (Visakha), Narasao and Miro (Mihara)."

- 10–11

- "And he gave same (or likewise) order to make images of these deities who have been written above."

- 11–14

- "And he ordered to make images and likenesses of these kings: for king Kujula Kadphises, for the great grandfather, and for this grandfather Saddashkana (Sadashkana), the Soma sacrificer, and for king V'ima Kadphises, for the father, and for himself (?), king Kanishka."

- 14–15

- "Then, as the king of kings, the son of god, had commanded to do, Shaphara, the master of the city, made this sanctuary."

- 16–17

- "Then, the master of the city, Shapara, and Nokonzoka led worship according to the royal command."

- 17–20

- "These gods who are written here, then may ensure for the king of kings, Kanishka, the Kushana, for remaining for eternal time healthy., secure and victorious... and further ensure for the son of god also having authority over the whole of India from the year one to the year thousand and thousand."

- 20

- "Until the sanctuary was founded in the year one, to (i.e. till) then the Great Arya year had been the fashion."

- 21

- "...According to the royal command, Abimo, who is dear to the emperor, gave capital to Pophisho."

- 22

- "...The great king gave (i.e. offered worship) to the deities."

- 23

- "..."

Note: This translation differs from Nicholas Sims-Williams, who has "Vima Taktu" as the grandfather of Kanishka (lines 11–14). Further, Sims-Williams does not read the words "Saddashkana" or "Soma" anywhere in the inscription.[4][5][6]

See also

- Pre-Islamic Hindu and Buddhist heritage of Afghanistan

Footnotes

- Karalrang means "Lord of the border land". See: Sundermann, Werner; Hintze, Almut; Blois, François de (2009). Exegisti Monumenta: Festschrift in Honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 216. ISBN 978-3-447-05937-4.

- "Devaputra" means "Son of the Gods" in Indian languages.

References

- See also the analysis of Sims-Williams and J.Cribb, who had a central role in the decipherment: "A new Bactrian inscription of Kanishka the Great", in "Silk Road Art and Archaeology" No.4, 1995–1996.

- B. N. Mukherjee, "The Great Kushana Testament", Indian Museum Bulletin, Calcutta, 1995; quoted in Ancient Indian Inscriptions, S.R. Goyal, 2005

- Here the greek transcription can be found.

- "Bactrian Documents from Ancient Afghanistan" at "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2007-05-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- Sims-Williams (1998), p.82

- Sims-Williams (2008), pp. 56–57.

Sources

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas and Cribb, Joe 1996, "A New Bactrian Inscription of Kanishka the Great", Silk Road Art and Archaeology, volume 4, 1995–6, Kamakura, pp. 75–142.

- Fussman, Gérard (1998). "L’inscription de Rabatak et l’origine de l’ère saka." Journal asiatique 286.2 (1998), pp. 571–651.

- Pierre Leriche, Chakir Pidaev, Mathilde Gelin, Kazim Abdoulaev, " La Bactriane au carrefour des routes et des civilisations de l'Asie centrale : Termez et les villes de Bactriane-Tokharestan ", Maisonneuve et Larose – IFÉAC, Paris, 2001 ISBN 2-7068-1568-X . Actes du colloque de Termez 1997. (Several authors, including Gérard Fussman « L'inscription de Rabatak. La Bactriane et les Kouchans » )

- S.R. Goyal "Ancient Indian Inscriptions" Kusumanjali Book World, Jodhpur (India), 2005.

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas (1998): "Further notes on the Bactrian inscription of Rabatak, with an Appendix on the names of Kujula Kadphises and Vima Taktu in Chinese." Proceedings of the Third European Conference of Iranian Studies Part 1: Old and Middle Iranian Studies. Edited by Nicholas Sims-Williams. Wiesbaden. 1998, pp. 79–93.

- Sims-Williams, Nicholas (2008). "The Bactrian Inscription of Rabatak: A New Reading." Bulletin of the Asia Institute 18, 2008, pp. 53–68.