Project Tiger

Project Tiger is a tiger conservation programme launched in April 1973 by the Government of India during Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's tenure.[1] Kailash Sankhala was the first director of Project Tiger.[2]

The project aims at ensuring a viable population of Bengal tigers in their natural habitats, protecting them from extinction, and preserving areas of biological importance as a natural heritage forever represented as close as possible the diversity of ecosystems across the distribution of tigers in the country. The project's task force visualized these tiger reserves as breeding nuclei, from which surplus animals would migrate to adjacent forests. Funds and commitment were mastered to support the intensive program of habitat protection and rehabilitation under the project.[3] The government has set up a Tiger Protection Force to combat poachers and funded relocation of villagers to minimize human-tiger conflicts.

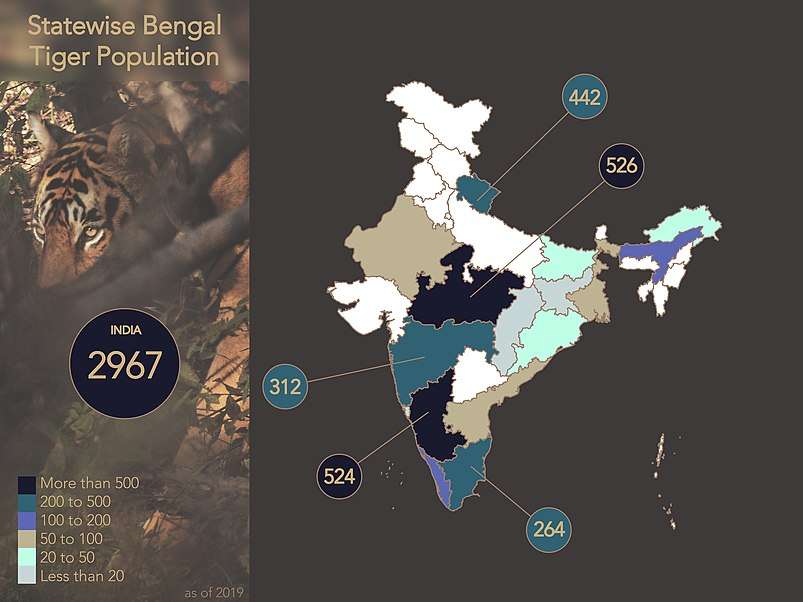

During the tiger census of 2006, a new methodology was used extrapolating site-specific densities of tigers, their co-predators and prey derived from camera trap and sign surveys using GIS. Based on the result of these surveys, the total tiger population was estimated at 1,411 individuals ranging from 1,165 to 1,657 adult and sub-adult tigers of more than 1.5 years of age.[4] Owing to the project, the number of tigers increased to 2,226 as per the census report released in 2015.[5] State surveys have reported a significant increase in the tiger population which was estimated at around 3,000 during the 2018 count (as part of a four yearly tiger census).[6]

Objectives

Project Tiger's main aims are to:

- reduce factors that lead to the depletion of tiger habitats and to mitigate them by suitable management. The damages done to the habitat shall be rectified so to facilitate the recovery of the ecosystem to the maximum possible extent.

- ensure a viable tiger population for economic, scientific, cultural, aesthetic and ecological values.

The monitoring system M-STrIPES was developed to assist patrol and protection of tiger habitats. It maps patrol routes and allows forest guards to enter sightings, events and changes when patrolling. It generates protocols based on these data, so that management decisions can be adapted.[7]

Management

Project Tiger was administered by the National Tiger Conservation Authority. The overall administration of the project is monitored by a steering committee, which is headed by a director. A field director is appointed for each reserve, who is assisted by a group of field and technical personnel.

- Shivalik-Terai Conservation Unit

- North-East Conservation Unit

- Sunderbans Conservation Unit

- Western Ghats Conservation Unit

- Eastern Ghats Conservation Unit

- Central India Conservation Unit

- Sariska Conservation Unit

- Kaziranga Conservation Unit

The various tiger reserves were created in the country based on the 'core-buffer' strategy:

- Core area: the core areas are free of all human activities. It has the legal status of a national park or wildlife sanctuary. It is kept free of biotic disturbances and forestry operations like collection of minor forest produce, grazing, and other human disturbances are not allowed within.

- Buffer areas: the buffer areas are subjected to 'conservation-oriented land use'. They comprise forest and non-forest land. It is a multi-purpose use area with twin objectives of providing habitat supplement to spillover population of wild animals from core conservation unit and to provide site specific co-developmental inputs to surrounding villages for relieving their impact on core area.

The important thrust areas for the Plan period are:

- Stepped up protection/networking surveillance.

- Voluntary relocation of people from core/critical tiger habitat to provide inviolate space for tiger.

- Use of information technology in wildlife crime prevention.

- Addressing human wildlife conflicts.

- Capacity building of frontier personnel.

- Developing a national repository of camera trap tiger photographs with IDs.

- Strengthening the regional offices of the NTCA.

- Declaring and consolidating new tiger reserves.

- Foresting awareness for eliciting new tiger reserves.

- Foresting Research.

For each tiger reserve, management plans were drawn up based on the following principles:

- Elimination of all forms of human exploitation and biotic disturbance from the core area and rationalization of activities in the buffer zone

- Restricting the habitat management only to repair the damages done to the ecosystem by human and other interferences so as to facilitate recovery of the ecosystem to its natural state

- Monitoring the faunal and floral changes over time and carrying out research about wildlife

By the late 1980s, the initial nine reserves covering an area of 9,115 square kilometers (3,519 square miles) had been increased to 15 reserves covering an area of 24,700 km2 (9,500 sq mi). More than 1100 tigers were estimated to inhabit the reserves by 1984.[3] By 1997, 23 tiger reserves encompassed an area of 33,000 km2 (13,000 sq mi), but the fate of tiger habitat outside the reserves was precarious, due to pressure on habitat, incessant poaching and large-scale development projects such as dams, industry and mines.[8]

Wireless communication systems and outstation patrol camps have been developed within the tiger reserves, due to which poaching has declined considerably. Fire protection is effectively done by suitable preventive and control measures. Voluntary Village relocation has been done in many reserves, especially from the core area. Live stock grazing has been controlled to a great extent in the tiger reserves. Various compensatory developmental works have improved the water regime and the ground and field level vegetation, thereby increasing the animal density. Research data pertaining to vegetation changes are also available from many reserves. Future plans include use of advanced information and communication technology in wildlife protection and crime management in tiger reserves, GIS based digitized database development and devising a new tiger habitat and population evaluation system.

Controversies and problems

Project Tiger's efforts were hampered by poaching, as well as debacles and irregularities in Sariska and Namdapha, both of which were reported extensively in the Indian media. The Forest Rights Act passed by the Indian government in 2006 recognizes the rights of some forest dwelling communities in forest areas. This has led to controversy over implications of such recognition for tiger conservation. Some have argued that this is problematic as it will increase conflict and opportunities for poaching; some also assert that "tigers and humans cannot co-exist".[9][10] Others argue that this is a limited perspective that overlooks the reality of human-tiger coexistence and the role of abuse of power by authorities, rather than local people, in the tiger crisis. This position was supported by the Government of India's Tiger Task Force, and is also taken by some forest dwellers' organizations.[11][12]

See also

- List of Indian states by tiger population

- Indian Council of Forestry Research and Education

- Tiger poaching in India

- Tiger reserves of India

References

- How to identify a tiger from its stripes (PDF). Project Tiger. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Sujit Mukherjee (1 January 1993). Forster and Further: The Tradition of Anglo-Indian Fiction. Orient Blackswan. pp. 222–. ISBN 978-0-86311-289-8.

- Panwar, H. S. (1987). "Project Tiger: The reserves, the tigers, and their future". In Tilson, R. L.; Sel, U. S. (eds.). Tigers of the world: the biology, biopolitics, management, and conservation of an endangered species. Park Ridge, N.J.: Minnesota Zoological Garden, IUCN/SSC Captive Breeding Group, IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 110–117.

- Jhala, Y. V., Gopal, R., Qureshi, Q. (eds.) (2008). Status of the Tigers, Co-predators, and Prey in India (PDF). TR 08/001. National Tiger Conservation Authority, Govt. of India, New Delhi; Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2013.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Tiger population grows". CNN IBN. 20 January 2015.

- "India's wild tiger population rises to nearly 3,000 – a drastic increase despite human conflict". CBS News. 29 July 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- National Tiger Conservation Authority, Wildlife Institute of India, Zoological Society of London (2010). ""MSTrIPES": Monitoring System for Tigers – Intensive Protection & Ecological Status" (PDF). India Environment Portal.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Thapar, V. (1999). The tragedy of the Indian tiger: starting from scratch. In: Seidensticker, J., Christie, S., Jackson, P. (eds.) Riding the Tiger. Tiger Conservation in human-dominated landscapes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. hardback ISBN 0-521-64057-1, paperback ISBN 0-521-64835-1. pp. 296–306.

- Buncombe, A. (31 October 2007) The face of a doomed species. The Independent

- Strahorn, Eric A. (1 January 2009). An Environmental History of Postcolonial North India: The Himalayan Tarai in Uttar Pradesh and Uttaranchal. Peter Lang. p. 118. ISBN 9781433105807.

- Government of India (2005) Tiger Task Force Report Archived 27 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- Campaign for Survival and Dignity Tiger Conservation: A Disaster in the Making Archived 11 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. forestrightsact.com