Proguanil

Proguanil, also known as chlorguanide and chloroguanide, is a medication used to treat and prevent malaria.[3][4] It is often used together with chloroquine or atovaquone.[4][3] When used with chloroquine the combination will treat mild chloroquine resistant malaria.[3] It is taken by mouth.[5]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Paludrine, others |

| Other names | chlorguanide, chloroguanide[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| Routes of administration | By mouth (tablets) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 75% |

| Metabolism | By liver (CYP2C19) |

| Metabolites | cycloguanil and 4-chlorophenylbiguanide |

| Elimination half-life | 12–21 hours[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.196 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

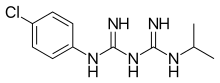

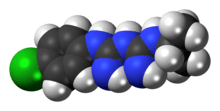

| Formula | C11H16ClN5 |

| Molar mass | 253.73 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 129 °C (264 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Side effects include diarrhea, constipation, skin rashes, hair loss, and itchiness.[3] Because malaria tends to be more severe in pregnancy, the benefit typically outweighs the risk.[3] If used during pregnancy it should be taken with folate.[3] It is likely safe for use during breastfeeding.[3] Proguanil is converted by the liver to its active metabolite, cycloguanil.[4]

Proguanil has been studied at least since 1945.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the safest and most effective medicines needed in a health system.[7] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.10–0.50 per day.[5] In the United States and Canada it is only available in combination as atovaquone/proguanil.[8]

Medical uses

Proguanil is used for the prevention and treatment of malaria in both adults and children, particularly in areas where chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum malaria has been reported. It is usually taken in combination with atovaquone, another antimalarial drug.[9]

It is also effective in the treatment of most other multi-drug resistant forms of P. falciparum; the success rate exceeds 93%.[10]

Side effects

Proguanil is generally well tolerated, and most people do not experience side effects. However, common side effects include abdominal pain, nausea, headache, and fever. Taking proguanil with food may lessen these side effects.[11] Proguanil should not be taken by people with severe renal impairment, pregnant women, or women who are breastfeeding children less than 5 kg.[12] There have also been reports of increased levels of liver enzymes, which may remain high for up to 4 weeks after completion of treatment.[13]

Mechanism

When used alone, proguanil functions as a prodrug. Its active metabolite, cycloguanil, is an inhibitor of dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR).[14] Although both mammals and parasites produce DHFR, cycloguanil's inhibitory activity is specific for parasitic DHFR. This enzyme is a critical component of the folic acid cycle. Inhibition of DHFR prevents the parasite from recycling dihydrofolate back to tetrahydrofolate (THF). THF is required for DNA synthesis, amino acid synthesis, and methylation; thus, DHFR inhibition shuts down these processes.[15]

Proguanil displays synergism when used in combination with the antimalarial atovaquone. This mechanism of action differs from when proguanil was used as a singular agent. In this case, it is not thought to function as a DHFR inhibitor. The addition of proguanil has shown to reduce resistance to atovaquone and increase the ability of atovaquone to trigger a mitochondrial apoptotic cascade.[16] This is commonly referred to as "collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential."[17] Proguanil lowers the effective concentration of atovaquone needed to increase permeability of the mitochondrial membrane.[18]

References

- Mehlhorn, Heinz (2008). Encyclopedia of Parasitology: A-M. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 388. ISBN 9783540489948. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- "Malarone (atovaquone/proguanil) Tablets, Pediatric Tablets. Full Prescribing Information" (PDF). GlaxoSmithKline. Research Triangle Park, NC 27709. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. pp. 199, 203. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- "Atovaquone and Proguanil Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "Proguanil". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Nzila, Alexis (2006-06-01). "The past, present and future of antifolates in the treatment of Plasmodium falciparum infection". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 57 (6): 1043–1054. doi:10.1093/jac/dkl104. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 16617066.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "Proguanil". www.medscape.com. Medscape. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- "Malaria: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-11-17. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- Boggild, Andrea K.; Parise, Monica E.; Lewis, Linda S.; Kain, Kevin C. (2007-02-01). "Atovaquone-Proguanil: Report from the Cdc Expert Meeting on Malaria Chemoprophylaxis (ii)". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 76 (2): 208–223. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2007.76.208. ISSN 0002-9637. PMID 17297027.

- "Atovaquone And Proguanil (Oral Route) Side Effects - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Archived from the original on 2016-11-09. Retrieved 2016-11-08.

- Prevention, CDC - Centers for Disease Control and. "CDC - Malaria - Travelers - Choosing a Drug to Prevent Malaria". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-11-13. Retrieved 2016-11-08.

- Looareesuwan, S.; Wilairatana, P.; Chalermarut, K.; Rattanapong, Y.; Canfield, C. J.; Hutchinson, D. B. (1999-04-01). "Efficacy and safety of atovaquone/proguanil compared with mefloquine for treatment of acute Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Thailand". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 60 (4): 526–532. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.526. ISSN 0002-9637. PMID 10348224.

- Pubchem. "proguanil | C11H16ClN5 - PubChem". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-11-14. Retrieved 2016-11-13.

- Boggild, Andrea K.; Parise, Monica E.; Lewis, Linda S.; Kain, Kevin C. (2007-02-01). "Atovaquone-Proguanil: Report from the CDC Expert Meeting on Malaria Chemoprophylaxis (ii)". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 76 (2): 208–223. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2007.76.208. ISSN 0002-9637. PMID 17297027.

- Srivastava, Indresh K.; Vaidya, Akhil B. (1999-06-01). "A Mechanism for the Synergistic Antimalarial Action of Atovaquone and Proguanil". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 43 (6): 1334–1339. doi:10.1128/AAC.43.6.1334. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 89274. PMID 10348748.

- Srivastava, Indresh K.; Rottenberg, Hagai; Vaidya, Akhil B. (1997-02-14). "Atovaquone, a Broad Spectrum Antiparasitic Drug, Collapses Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in a Malarial Parasite". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (7): 3961–3966. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.7.3961. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 9020100.

- Thapar, MM; Gupta, S; Spindler, C; Wernsdorfer, WH; Björkman, A (May 2003). "Pharmacodynamic Interactions Among Atovaquone, Proguanil and Cycloguanil against Plasmodium falciparum in vitro". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 97 (3): 331–7. doi:10.1016/S0035-9203(03)90162-3. PMID 15228254.

External links

- "Proguanil". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.