Post-resurrection appearances of Jesus

The post-resurrection appearances of Jesus are the reported earthly appearances of Jesus to his followers after his death and burial. Believers point to them as evidence of his resurrection and identity as Messiah, seated in Heaven on the right hand of God (the doctrine of the Exaltation of Christ).[1] Others interpret these accounts as visionary experiences.

| Part of a series on |

| Death and Resurrection of Jesus |

|---|

|

|

|

Visions of Jesus

|

|

Empty tomb fringe theories |

|

Related |

|

Portals: |

Background

| Events in the |

| Life of Jesus according to the canonical gospels |

|---|

|

|

In rest of the NT |

|

Portals: |

The resurrection of the flesh was a marginal belief in Second Temple Judaism, i.e., Judaism of the time of Jesus.[2] The idea of any resurrection at all first emerges clearly in the 2nd-century-BC Book of Daniel, but as a belief in the resurrection of the soul alone.[3] A few centuries later the Jewish historian Josephus, writing roughly in the same period as Paul and the authors of the gospels, says that the Essenes believed the soul to be immortal, so that while the body would return to dust the soul would go to a place fitting its moral character, righteous or wicked.[4] This, according to the gospels, was the stance of Jesus, who defended it in an exchange with the Sadducees: "Those who are accounted worthy ... to the resurrection from the dead neither marry nor are given in marriage, for they ... are equal to the angels and are children of God..." (Mark 12:24–25, Luke 20:34–36).[5]

The Greeks, by contrast, had long held that a meritorious man could be resurrected as a god after his death (the process of apotheosis).[6] The successors of Alexander the Great made this idea very well known throughout the Middle East, in particular through coins bearing his image – a privilege previously reserved for gods – and although originally foreign to the Romans, the doctrine was soon borrowed by the emperors for purposes of political propaganda.[6] According to the theology of Imperial Roman apotheosis, the earthly body of the recently deceased emperor vanished, he received a new and divine one in its place, and was then seen by credible witnesses;[7] thus, in a story similar to the Gospel appearances of the resurrected Jesus and the commissioning of the disciples, Romulus, the founder of Rome, descended from the sky to command a witness to bear a message to the Romans regarding the city's greatness ("Declare to the Romans the will of Heaven that my Rome shall be the capital of the world...") before being taken up on a cloud.[8]

The experiences of the risen Christ attested by the earliest written sources – the "primitive Church" creed of 1 Corinthians 15:3–5, Paul in 1 Corinthians 15:8 and Galatians 1:16 – are ecstatic rapture events and "invasions of heaven".[9] A physical resurrection was unnecessary for this visionary mode of seeing the risen Christ, but the general movement of subsequent New Testament literature is towards the physical nature of the resurrection.[10] This development can be linked to the changing make-up of the Christian community: Paul and the earliest Christ-followers were Jewish, and Second Temple Judaism emphasised the life of the soul; the gospel-writers, in an overwhelmingly Greco-Roman church, stressed instead the pagan belief in the hero who is immortalised and deified in his physical body.[11] In this Hellenistic resurrection paradigm Jesus dies, is buried, and his body disappears (with witnesses to the empty tomb); he then returns in an immortalised physical body, able to appear and disappear at will like a god, and returns to the heavens which are now his proper home.[12]

Biblical accounts

Earliest Jewish-Christian followers of Jesus

The earliest report of the post-Resurrection appearances of Jesus is in Paul's First Epistle to the Corinthians.[13] This lists, apparently in chronological order, a first appearance to Peter, then to "the Twelve," then to five hundred at one time, then to James (presumably James the brother of Jesus), then to "all the Apostles," and last to Paul himself.[13] Paul does not mention any appearances to women, apart from "sisters" included in the 500; other New Testament sources do not mention any appearance to a crowd of 500.[13] There is general agreement that the list is pre-Pauline – it is often called a catechism of the early church – but less on how much of the list belongs to the tradition and how much is from Paul: most scholars feel that Peter and the Twelve are original, but not all believe the same of the appearances to the 500, James and "all the Apostles".[14][note 1]

Pauline epistles

By claiming that Jesus has appeared to him in the same way he did to Peter, James and the others who had known Jesus in life, Paul bolsters his own claims to apostolic authority.[15] In Galatians 1 he explains that his experience was a revelation both from Jesus ("The gospel I preached ... I received by revelation from Jesus Christ") and of Jesus ("God ... was pleased to reveal His son in me").[16] In 2 Corinthians 12 he tells his readers of "a man in Christ who ... was caught up to the third heaven. Whether it was in the body or out of the body I do not know – God knows;"[17] Elsewhere in the Epistles Paul speaks of "glory" and "light" and the "face of Jesus Christ," and while the language is obscure it is plausible that he saw Jesus exalted, enthroned in heaven at the right hand of God.[17] He has little interest in Jesus' resurrected body, except to say that it is not a this-worldly one: in his Letter to the Philippians he describes how the resurrected Christ is exalted in a new body utterly different from one he had when he wore "the appearance of a man," and holds out a similar glorified state, when Christ "will transform our lowly body," as the goal of the Christian life.[18]

Gospels and Acts

The Gospel of Mark (written c. 70 CE) contained no post-Resurrection appearances in its original version, which ended at Mark 16:8, although Mark 16:7, in which the young man discovered in the tomb instructs the women to tell "the disciples and Peter" that Jesus will see them again in Galilee, hints that the author may have known of the tradition of 1 Thessalonians.[19][20][21]

The authors of Matthew (c. 80 – c. 90 CE) and Luke–Acts (a two-part work by the same anonymous author, usually dated to around 80–90 CE) based their lives of Jesus on the Gospel of Mark.[22][23] As a result, they diverge widely after Mark 16:8, where Mark ends with the discovery of the empty tomb. Matthew has two post-Resurrection appearances, the first to Mary Magdalene and "the other Mary" at the tomb, and the second, based on Mark 16:7, to all the disciples on a mountain in Galilee, where Jesus claims authority over heaven and Earth and commissions the disciples to preach the gospel to the whole world.[24] Luke does not mention any of the appearances reported by Matthew,[25] explicitly contradicts him regarding an appearance at the tomb (Luke 24:24), and replaces Galilee with Jerusalem as the sole location.[20] In Luke, Jesus appears to Cleopas and an unnamed disciple on the road to Emmaus, to Peter (reported by the other apostles), and to the eleven remaining disciples at a meeting with others. The appearances reach their climax with the Ascension of Jesus before the assembled disciples on a mountain outside Jerusalem. In addition, Acts has appearances to Paul on the Road to Damascus, to the martyr Stephen, and to Peter, who hears the voice of Jesus.

The Gospel of John was written some time after 80 or 90 CE.[26] Jesus appears at the empty tomb to Mary Magdalene (who initially fails to recognise him), then to the disciples minus Thomas, then to all the disciples including Thomas (the "doubting Thomas" episode), finishing with an extended appearance in Galilee to Peter and six (not all) of the disciples.[27] Chapter 21, the appearance in Galilee, is widely believed to be a later addition to the original gospel.[28]

Theological implications

The earliest Jewish followers of Jesus (the Jewish Christians) understood him as the Son of Man in the Jewish sense, a human who, through his perfect obedience to God's will, was resurrected and exalted to heaven in readiness to return at any moment as the Son of Man, the supernatural figure seen in Daniel 7:13–14, ushering in and ruling over the Kingdom of God.[29] Paul has already moved away from this apocalyptic tradition towards a position where Christology and soteriology take precedence: Jesus is no longer the one who proclaims the message of the imminently coming Kingdom, he actually is the kingdom, the one in whom the kingdom of God is already present.[30]

This is also the message of Mark, a Gentile writing for a church of Gentile Christians, for whom Jesus as "Son of God" has become a divine being whose suffering, death and resurrection are essential to God's plan for redemption.[31] Matthew presents Jesus' appearance in Galilee (Matthew 28:16–17) as a Greco-Roman apotheosis, the human body transformed to make it fitting for paradise.[32] He goes beyond the ordinary Greco-Roman forms, however, by having Jesus claim "all authority ... in heaven and on earth" (28:18) – a claim no Roman hero would dare make – while charging the apostles to bring the whole world into a divine community of righteousness and compassion.[33] Notable too is that the expectation of the imminent Second Coming has been delayed: it will still come about, but first the whole world must be gathered in.[33]

In Paul and the first three gospels, and also in Revelation, Jesus is portrayed as having the highest status, but the Jewish commitment to monotheism prevents the authors from depicting him as fully one with God.[34] This stage was reached first in the Christian community which produced the Johannine literature: only here in the New Testament does Jesus become God incarnate, the body of the resurrected Jesus bringing Doubting Thomas to exclaim, "My Lord and my God!"[35][36]

Explanations

Evolution of resurrection beliefs

The appearances of Jesus are often explained as visionary experiences, in which the presence of Jesus was felt.[9][37][38][39][40] A physical resurrection was unnecessary for the visionary mode of seeing the risen Christ, but when the gospels of Matthew, Luke and John were being written, the emphasis had shifted to the physical nature of the resurrection, while still overlapping with the earlier concept of a divine exaltation of Jesus' soul.[10] This development can be linked to the changing make-up of the Christian community: Paul and the earliest Christ-followers were Jewish, and Second Temple Judaism emphasised the life of the soul; the gospel-writers, in an overwhelmingly Greco-Roman church, stressed instead the pagan belief in the hero who is immortalised and deified in his physical body.[11]

Furthermore, New Testament scholar James Dunn argues that whereas the apostle Paul's resurrection experience was "visionary in character" and "non-physical, non-material," the accounts in the Gospels and of the apostles mentioned by Paul are very different. He contends that the "massive realism' [...] of the [Gospel] appearances themselves can only be described as visionary with great difficulty - and Luke would certainly reject the description as inappropriate," and that the earliest conception of resurrection in the Jerusalem Christian community was physical.[41]

Subjective vision theory

David Friedrich Strauss (1808–1874), in his "Life of Jesus" (1835), argued that the resurrection was not an objective historical fact, but a subjective "recollection" of Jesus, transfiguring the dead Jesus into an imaginary, or "mythical," risen Christ.[1] The appearance, or Christophany, of Jesus to Paul and others, was "internal and subjective."[42] Reflection on the Messianic hope, and Psalms 16:10,[note 2] led to an exalted state of mind, in which "the risen Christ" was present "in a visionary manner," concluding that Jesus must have escaped the bondage of death.[42] Strauss' thesis was further developed by Ernest Renan (1863) and Albert Réville (1897).[43] These interpretations were later classed the "subjective vision hypothesis",[note 3] and "is advocated today by a great majority of New Testament experts."[44]

According to Ehrman, "the Christian view of the matter [is] that the visions were bona fide appearances of Jesus to his followers",[45] a view which is "forcefully stated in any number of publications."[45] Ehrman further notes that "Christian apologists sometimes claim that the most sensible historical explanation for these visions is that Jesus really appeared to the disciples."[46]

According to De Conick, the experiences of the risen Christ in the earliest written sources – the "primitive Church" creed of 1 Corinthians 15:3-5, Paul in 1 Corinthians 15:8 and Galatians 1:16 – are ecstatic rapture events.[9]

Exaltation of Jesus

According to Hurtado, the resurrection experiences were religious experiences which "seem to have included visions of (and/or ascents to) God's heaven, in which the glorified Christ was seen in an exalted position."[47] These visions may mostly have appeared during corporate worship.[39] Johan Leman contends that the communal meals provided a context in which participants entered a state of mind in which the presence of Jesus was felt.[40]

According to Ehrman, "the disciples' belief in the resurrection was based on visionary experiences."[48][note 4] Ehrman notes that both Jesus and his early followers were apocalyptic Jews, who believed in the bodily resurrection, which would start when the coming of God's Kingdom was near.[50] Ehrman further notes that visions usually have a strong persuasive power, but that the Gospel-accounts also record a tradition of doubt about the appearances of Jesus. Ehrman's "tentative suggestion" is that only a few followers had visions, including Peter, Paul and Mary. They told others about those visions, convincing most of their close associates that Jesus was raised from the dead, but not all of them. Eventually, these stories were retold and embellished, leading to the story that all disciples had seen the risen Jesus.[51] The belief in Jesus' resurrection radically changed their perceptions, concluding from his absence that he must have been exalted to heaven, by God himself, exalting him to an unprecedented status and authority.[52]

Call to missionary activity

According to Helmut Koester, the stories of the resurrection were originally epiphanies in which the disciples are called to a ministry by the risen Jesus, and at a secondary stage were interpreted as physical proof of the event. He contends that the more detailed accounts of the resurrection are also secondary and do not come from historically trustworthy sources, but instead belong to the genre of the narrative types.[53]

According to Gerd Lüdemann, Peter had a vision of Jesus, induced by his feelings of guilt of betraying Jesus. The vision elevated this feeling of guilt, and Peter experienced it as a real appearance of Jesus, raised from dead. He convinced the other disciples that the resurrection of Jesus signalled that the endtime was near and God's Kingdom was coming, when the dead who would rise again, as evidenced by Jesus. This revitalized the disciples, starting-off their new mission.[web 1]

According to Biblical scholar Géza Vermes, the resurrection is to be understood as a reviving of the self-confidence of the followers of Jesus, under the influence of the Spirit, "prompting them to resume their apostolic mission." They felt the presence of Jesus in their own actions, "rising again, today and tomorrow, in the hearts of the men who love him and feel he is near."[54]

See also

- Ascension of Jesus

- Empty tomb

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

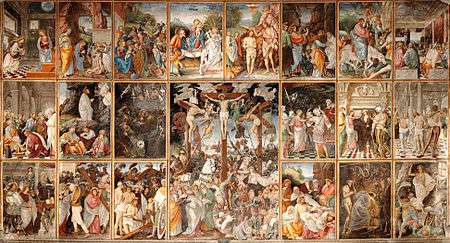

- Resurrection of Jesus in Christian art

- Third Nephi, post-resurrection appearance of Jesus to people in the Americas as recounted in The Book of Mormon

Notes

- Paul informs his readers that he is passing on what he has been told, "that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, and then to the Twelve. After that, he appeared to more than five hundred of the brothers and sisters at the same time, most of whom are still living, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles, and last of all he appeared to me also, as to one abnormally born."

- See also Herald Gandi (2018), The Resurrection: "According to the Scriptures"?

- Gregory W. Dawes (2001), The Historical Jesus Question, page 334: "[Note 168] Pannenberg classes all these attempts together under the heading of "the subjective vision hypothesis."; "[Note 169] In the present study, we have seen this hypothesis exemplified in the work of David Friedrich Strauss."

- Ehrman dismisses the story of the empty tomb; accoridng to Ehrman, "an empty tomb had nothing to do with it [...] an empty tomb would not produce faith."[49]

References

Citations

- McGrath 2011, p. 310.

- Endsjø 2009, p. 145.

- Schäfer 2003, p. 72–73.

- Finney 2016, p. 79.

- Tabor 2013, p. 58.

- Cotter 2001, p. 131.

- Cotter 2001, p. 133–135.

- Collins 2009, p. 46.

- De Conick 2006, p. 6.

- Finney 2016, p. 181.

- Finney 2016, p. 183.

- Finney 2016, p. 182.

- Taylor 2014, p. 374.

- Plevnik 2009, p. 4-6.

- Lehtipuu 2015, p. 42.

- Pate 2013, p. 39, fn.5.

- Chester 2007, p. 394.

- Lehtipuu 2015, p. 42-43.

- Reddish 2011, p. 74.

- Telford 1999, p. 149.

- Parker 1997, p. 125.

- Charlesworth 2008, p. unpaginated.

- Burkett 2002, p. 195.

- Cotter 2001, p. 127.

- McEwen, p. 134.

- Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 887–888.

- Quast 1991, p. 130.

- Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 888.

- Telford 1999, p. 154–155.

- Telford 1999, p. 156.

- Telford 1999, p. 155.

- Cotter 2001, p. 149.

- Cotter 2001, p. 150.

- Chester 2016, p. 15.

- Chester 2016, p. 15–16.

- Vermes 2001, p. unpaginated.

- Koester 2000, p. 64-65.

- Vermes 2008b, p. 141.

- Hurtado 2005, p. 73.

- Leman2015, p. 168-169.

- James D.G. Dunn, Jesus and the Spirit: A Study of the Religious and Charismatic Experience of Jesus and the First Christians as Reflected in the New Testament. Eerdmans, 1997. p. 115, 117.

- Garrett 2014, p. 100.

- Rush Rhees (2007), The Life of Jesus of Nazareth: "This last explanation has in recent times been revived in connection with the so-called vision-hypothesis by Renan and Réville."

- Kubitza 2016.

- Ehrman 2014, p. 100.

- Ehrman 2014, p. 107.

- Hurtado 2005, p. 72–73.

- Ehrman 2014, p. 98, 101.

- Ehrman 2014, p. 98.

- Ehrman 2014, p. 99.

- Ehrman 2014, p. 101-102.

- Ehrman 2014, p. 109-110.

- Koester 2000, p. 64–65.

- Vermes 2008a, p. 151–152.

Sources

- Printed sources

- Barton, John; Muddiman, John (2010). The Pauline Epistles. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191034664.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burkett, Delbert (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521007207.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Charlesworth, James H. (2008). The Historical Jesus: An Essential Guide. Abingdon Press. ISBN 9781426724756.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chester, Andrew (2007). Messiah and Exaltation: Jewish Messianic and Visionary Traditions and New Testament Christology. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161490910.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, Adela Yarbro (2009). "Ancient Notions of Transferal and Apotheosis". In Seim, Turid Karlsen; Økland, Jorunn (eds.). Metamorphoses: Resurrection, Body and Transformative Practices in Early Christianity. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110202991.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cotter, Wendy (2001). "Greco-Roman Apotheosis Traditions and the Resurrection in Matthew". In Thompson, William G. (ed.). The Gospel of Matthew in Current Study. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802846730.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- De Conick, April D. (2006). Paradise Now: Essays on Early Jewish and Christian Mysticism. SBL. ISBN 9781589832572.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ehrman, Bart (2014), How Jesus Became God. The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilea, Harperone

- Endsjø, D. (2009). Greek Resurrection Beliefs and the Success of Christianity. Springer. ISBN 9780230622562.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Finney, Mark (2016). Resurrection, Hell and the Afterlife: Body and Soul in Antiquity, Judaism and Early Christianity. Routledge. ISBN 9781317236375.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garrett, James Leo (2014), Systematic Theology, Volume 2, Second Edition: Biblical, Historical, and Evangelical, Volume 2, Wipf and Stock Publishers

- Lehtipuu, Outi (2015). Debates Over the Resurrection of the Dead: Constructing Early Christian Identity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198724810.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hurtado, Larry (2005), Lord Jesus Christ. Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity, Eerdmans

- Koester, Helmut (2000), Introduction to the New Testament, Vol. 2: History and Literature of Early Christianity, Walter de Gruyter

- Kubitza, Heinz-Werner (2016), The Jesus Delusion: How the Christians created their God: The demystification of a world religion through scientific research, Tectum Wissenschaftsverlag

- Leman, Johan (2015), Van totem tot verrezen Heer. Een historisch-antropologisch verhaal, Pelckmans

- McGrath, Alister E. (2011). Christian Theology: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444397703.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Parker, D.C. (1997). The Living Text of the Gospels. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521599511.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pate, C. Marvin (2013). Apostle of the Last Days: The Life, Letters and Theology of Paul. Kregel Academic. ISBN 9780825438929.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perkins, Pheme (2014). "Resurrection of Jesus". In Evans, Craig A. (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. Routledge. ISBN 9781317722243.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Plevnik, Joseph (2009). What are They Saying about Paul and the End Time?. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809145782.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Quast, Kevin (1991). Reading the Gospel of John: An Introduction. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809132973.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reddish, Mitchell G. (2011). An Introduction to The Gospels. Abingdon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vermes, Geza (2001). The Changing Faces of Jesus. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780141912585.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schäfer, Peter (2003). The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World. Routledge. ISBN 9781134403165.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Swinburne, Richard (2003). The Resurrection of God Incarnate. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780199257454.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tabor, James (2013). Paul and Jesus: How the Apostle Transformed Christianity. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439123324.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, Mark (2014). 1 Corinthians: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture. B&H Publishing. ISBN 9780805401288.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Telford, W.R. (1999). The Theology of the Gospel of Mark. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521439770.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Van Voorst, Robert E. (2000). "Eternal Life". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vermes, Geza (2008a), The Resurrection, London: Penguin

- Vermes, Geza (2008b), The Resurrection: History and Myth, New York: Doubleday, ISBN 978-0-7394-9969-6

- Web-sources

- Bart Ehrman (5 oct. 2012), Gerd Lüdemann on the Resurrection of Jesus

External links

- Resurrection of Jesus Christ from the Catholic Encyclopedia

- a commentary on the appearances according to John, written by John Calvin