Pinhas Rutenberg

Pinhas Rutenberg (5 February 1879 – 3 January 1942; Russian: Пётр Моисеевич Рутенберг, Pyotr Moiseyevich Rutenberg; Hebrew: פנחס רוטנברג) was a Russian Jewish engineer, businessman, and political activist. He played an active role in two Russian revolutions, in 1905 and 1917. During World War I, he was among the founders of the Jewish Legion and of the American Jewish Congress. Later, through his connections in Palestine, he managed to obtain a concession for production and distribution of electric power and founded the Palestine Electric Corporation, currently the Israel Electric Corporation. A vocal and committed Zionist, Rutenberg also participated in establishing the Haganah, the main Jewish militia in pre-war Palestine, and founded Palestine Airways. He subsequently served as a President of the Jewish National Council.

Pinhas Rutenberg | |

|---|---|

Pinhas Rutenberg c. 1940 | |

| Born | 5 February 1879 |

| Died | 3 January 1942 (aged 62) |

Socialist and revolutionary

Pinhas Rutenberg was born in the town of Romny, north of Poltava, Russian Empire (now in Ukraine). After graduating from a practical high school, he enrolled to the Technology Institute in Saint Petersburg and joined the Socialist-Revolutionary Party (also known as the S.R. or Eser party). He worked as a workshop manager at the Putilov plant, the largest Petersburg industry. The plant was a center of the Assembly of Russian Factory and Plant Workers, founded in 1903 by a popular working class leader, Father George Gapon. Gapon collaborated in secret with the Police Department (the Okhrana), which believed this to be the way to control the workers' movement. Rutenberg became Gapon’s friend, which made him a noticeable figure in the S.R. party.

On Sunday 9 January 1905 (Old Style date) Gapon organized a "peaceful workers’ procession" to the Winter Palace in order to present a petition to the Tzar. Rutenberg participated, by his party's approval. In a tragic turn of events, army pickets fired directly into the crowd, and hundreds were killed. Amid the panic, Rutenberg retained self-control and actually saved Gapon’s life, taking him away from gun fire. This incident, known as Bloody Sunday, sparked the first Russian Revolution of 1905.

Gapon and Rutenberg fled abroad, being welcomed in Europe both by prominent Russian emigrants Georgy Plekhanov, Vladimir Lenin, and French socialist leaders Jean Jaurès and Georges Clemenceau. Before the end of 1905, Rutenberg returned to Russia, and Gapon followed him.

Gapon soon revealed to Rutenberg his contacts with the police and tried to recruit him, too, reasoning that double loyalty is helpful to the workers’ cause. However, Rutenberg betrayed his trust and reported this provocation to his party leaders, Yevno Azef and Boris Savinkov. Azef demanded that the traitor be put to death. Ironically, he was in fact an agent provocateur himself, exposed by Vladimir Burtsev in 1908.

On 26 March 1906 Gapon arrived to meet Rutenberg in a rented cottage out of St. Petersburg, and after a month he was found there hanged. Rutenberg asserted later that Gapon was condemned by a comrades’ court and that three S.R. party combatants overheard their conversation from the next room. After Gapon had repeated his collaboration proposal, Rutenberg called the comrades into the room and he left. When he returned, Gapon was dead.

However, the S.R. party leadership refused to assume responsibility, announcing that the execution was undertaken by Rutenberg individually and the cause was a personal one, denying ever having sent their comrades to the meeting on 26 March. Rutenberg was then condemned and expelled from the party.

Turn to Zionism

Forced to emigrate, Rutenberg settled in Italy. Away from politics, he concentrated on hydraulic engineering. Pondering on specific Jewish problems, he became convinced that the solution was to establish a national home for the Jewish people.

After World War I broke out, the Zionist movement mainly supported the Entente Powers. Rutenberg set the goal to create a Jewish armed force to fight for the Land of Israel. He visited European capitals, met prominent politicians and Zionist leaders, and finally joined the efforts of Jabotinsky and Trumpeldor to set up the Jewish Legion. In May 1915, on Jabotinsky’s approval, Rutenberg travelled to the United States to promote this idea among the American Jewry.

He found strong support among Jewish organizations in New York City. Rutenberg endorsed the labour party (Poalei Zion) and cooperated with David Ben-Gurion, Itzhak Ben-Zvi, and Ber Borochov. Together with Chaim Zhitlowsky, he founded the American Jewish Congress. At the same time, Rutenberg published his book The National Revival of the Jewish People under the pseudonym Pinhas Ben-Ami (in Hebrew: my people’s son).

While in the US, Rutenberg managed to complete a detailed design for utilizing the Land of Israel's hydraulic resources for irrigation and electrical power production, which was his long-time dream.

Anti-Bolshevik

Rutenberg greeted the Russian February Revolution of 1917, and in July 1917 he returned to Petrograd, welcomed by the prime minister of the Russian Provisional Government, Alexander Kerensky, also an S.R party member. Despite 12 years of absence in Russia, Rutenberg was soon named vice-president of the Petrograd municipality, the local Duma.

In a couple of months, Petrograd Soviet, headed by Leon Trotsky, became an alternative power in the capital, hostile towards the Duma. It was clear that the Soviets were planning to overthrow the government. On 3 November Rutenberg became a member of the emergency Supreme Council, created by Kerensky to preserve order and justice. During an assault on the Winter Palace on 7 November, the night of the October Revolution, Rutenberg defended the government residence after Kerensky had escaped. When the Bolsheviks prevailed, he was arrested and put in jail, together with the "capitalist ministers".

In March 1918, when German troops approached Petrograd, the Bolsheviks released Rutenberg, among many others. He moved to Moscow, the new capital, and took a position in the cooperative movement. However, after the unsuccessful attempt upon Lenin's life by Fanny Kaplan in August 1918, the "Red Terror" campaign against "Esers" was launched. Rutenberg escaped from Moscow. His last location in Russia was in the port city of Odessa, where he was a member of the defense committee. The city was governed by White Russians who were supported by the French Allied army. On 17 March 1919 he managed to obtain a Russian passport and with an exit visa boarded an American vessel that took him to the Allied-controlled city of Constantinople. From there he sailed to Marseille, later going on to the UK before departing to British Palestine.

In Palestine

In 1919, Rutenberg appeared in Paris and joined other Zionist leaders, preparing propositions for the Treaty of Versailles. Promoting the electrification plan, he received financial support from Baron Edmond James de Rothschild and his son James A. de Rothschild and, finally, settled in Palestine to realize it.

However, his first contribution after arrival was establishing, together with Jabotinsky, the Jewish self-defense militia, the Haganah. Rutenberg was the chief officer of these troops in Tel Aviv during the Arab hostilities in 1921.

He participated in the demarcation of Mandatory Palestine's northern border, defining British and French areas of interest.

In 1921 – over fierce Arab-Palestinian protests against giving the Yishuv an economic stranglehold of the country – the British granted Rutenberg the Jaffa and (later) the Jordan electricity concessions. The Jaffa concession had been the first to have been executed. Operating under the name of the Jaffa Electric Company, Rutenberg in 1923 built a grid that gradually covered Jaffa, Tel-Aviv, neighboring (mainly Jewish) settlements, and the British military installations in Sarafend. The grid was powered by diesel engines, in contrast to the original commitment of Rutenberg to build a hydro-electric power station on the Auja (Yarkon) river.[1] In 1923, Rutenberg founded the Palestine Electric Corporation. Following initial difficulties in launching the project, he sought and received support from then Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill.[2] Rutenberg invited influential British politics, Lord Herbert Samuel and Lord Reading, as well as Hugo Hirst, the Director of The General Electric Company, to be members of his Corporation Council.

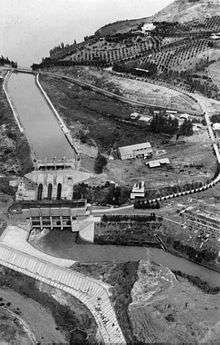

The formidable achievement of Rutenberg was the "First Jordan Hydro-Electric Power House" at Naharayim on the Jordan River, which opened in 1930, and earned him the nickname "The Old Man of Naharayim".[3] Other power plants were built in Tel Aviv, Haifa, Tiberias which supplied all of Palestine.[4] Jerusalem was the only part of the Mandatory Palestine not supplied by Rutenberg's plants. The concession for Jerusalem was granted by the Ottoman Empire to Greek Euripides Mavromatis. After Palestine was conquered by British forces, Mavromatis resisted Palestine Electric Company's attempts of building a power station that would serve Jerusalem. Only in 1942, when his British-Jerusalem Electric Corporation failed to supply the demands of the city, did the Mandatory government ask the Palestine Electric Company to take over the responsibility for supplying electricity to Jerusalem.[5]

Rutenberg died in 1942 in Jerusalem. A large modern power station near Ashkelon is named after him. Additionally, streets in Ramat Gan and Netanya are named in his honor.

References

- Shamir, Ronen (2013) "Current Flow: The Electrification of Palestine". Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- "The Seventh Dominion?". Time magazine. 4 March 1929. Retrieved 24 May 2007.

- Avitzur, Shmuel. "The Power Plant on Two Rivers". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- "Zion, Ten Years After". Time magazine. 4 April 1932. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- Naor, Mordechai (25 January 2004). "An electrifying story". Haaretz. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pinhas Rutenberg. |