Picpus Cemetery

Picpus Cemetery (French: Cimetière de Picpus) is the largest private cemetery in Paris, France, located in the 12th arrondissement. It was created from land seized from the convent of the Chanoinesses de St-Augustin, during the French Revolution. Just minutes away from where the guillotine was set up, it contains 1,306 victims executed between 14 June and 27 July 1794, during the height of the Reign of Terror. Today only descendants of those 1,306 victims are eligible to be buried at Picpus Cemetery.[1]

Cemetery entrance next to chapel Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix | |

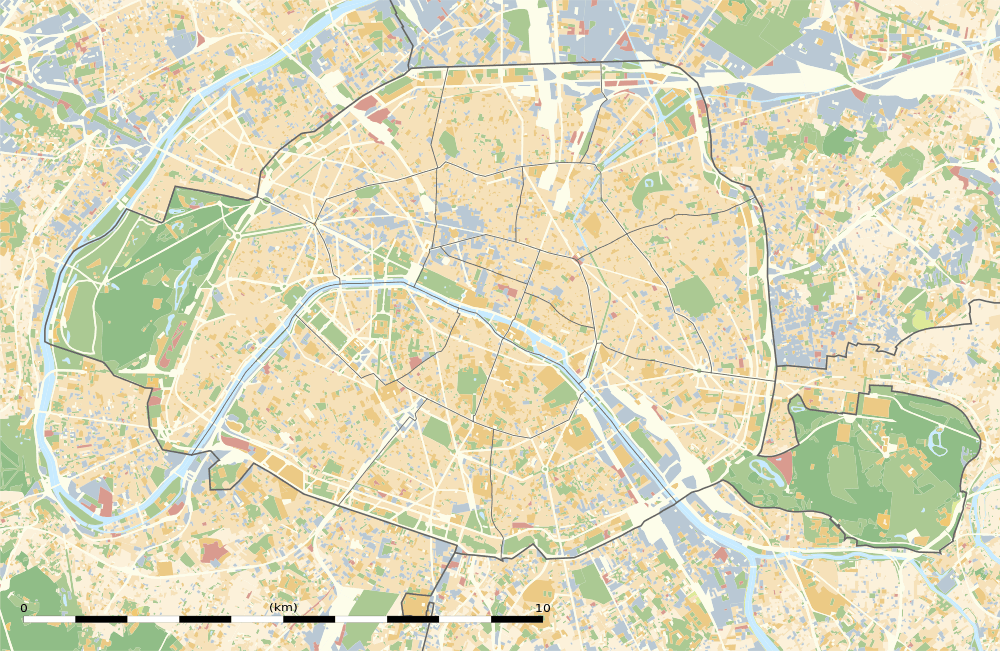

Location within Paris | |

| Details | |

|---|---|

| Established | 13 June 1794 |

| Location | 35 rue de Picpus, Paris |

| Country | |

| Coordinates | 48.8440°N 2.4001°E |

| Type | Private |

| Size | 2.1 hectares (5.2 acres) |

| No. of graves | unknown |

| No. of interments | 1,306 (two mass graves) |

| Find a Grave | Cimetière de Picpus |

Picpus Cemetery is one of only two private cemeteries in Paris, the other being the old Cimetière des Juifs Portugais de Paris in the 19th arrondissement.

Picpus Cemetery is situated next to a small chapel, Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix ("Our Lady of Peace"), run by the Sisters of the Sacred Heart. The priests of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts are referred to as "The Picpus Fathers" because of the order's origins on the street. It holds a small 15th-century sculpture of the Vierge de la Paix, reputed to have cured King Louis XIV of a serious illness on 16 August 1658.[2]

The cemetery is of particular interest to American visitors as it also holds the tomb of the Marquis de Lafayette (1757–1834), over which an American flag is always present.[3]

Location

The entrance to the cemetery is at 35 rue de Picpus in the 12th arrondissement. It can be visited in the afternoon every day except Sunday and holidays, with hours usually from 2 pm to 4 pm (Admission: €2). The Chapel of Our Lady of Peace is located at the entrance of the cemetery. The nearest Paris metro stations are Nation and Picpus.

Reign of Terror

During the French Revolution, the guillotine was set up in the Place de la Nation, then called the Place du Trône Renversé. Between 13 June and 28 July, during the time known as the Reign of Terror, as many as 55 people per day were executed.

The Revolutionary Tribunal needed a quick but anonymous way to dispose of the bodies. The cemetery is only five minutes from the Place de la Nation.

A pit was dug at the end of the garden where the decapitated bodies were thrown in together, noblemen and nuns, grocers and soldiers, laborers and innkeepers. A second pit was dug when the first filled up.

The names of those buried in the two common pits, 1,306 men and women, are inscribed on the walls of the chapel. Of the 1,109 men, there were 108 nobles, 108 churchmen, 136 monastics (gens de robe), 178 military, and 579 commoners. There are 197 women buried there, with 51 from the nobility, 23 nuns and 123 commoners. The bloodshed stopped when Robespierre himself was beheaded, and the garden was closed off.

Among the women, 16 Carmelite nuns ranging in age from 29 to 78, were brought to the guillotine together, singing hymns as they were led to the scaffold, an incident commemorated in Poulenc's opera, Dialogues of the Carmelites. They were beatified in 1906 as the Martyrs of Compiègne.

Post-Revolution

In 1797, under the Directory, the land was secretly acquired by Princess Amalie Zephyrine of Salm-Kyrburg, whose brother, Frederick III, Prince of Salm-Kyrburg, was buried in one of the common graves. In 1803, when Napoleon was First Consul, a group of family members of aristocrats bought up the rest of the land, and built a second cemetery next to the common graves.

In a meeting held in 1802, underwriters designated 11 of them to form a committee:

- Madame Montagu, née L. D. de Noailles, President

- Maurice de Montmorency

- Mr. Aimard de Nicolaï

- Madame Rebours, née Barville

- Madame Freteau widow, née Moreau

- Madame de La Fayette, née Adrienne de Noailles

- Madame Titon, née Benterot

- Madame Faudoas, née de Bernières

- Madame Charton, née Chauchat

- Philippe de Noailles de Poix

- Theodule M. de Grammont

Many of these noble families still use the cemetery as a place of burial.

The Marquis de Lafayette

Arguably Picpus Cemetery's most famous tomb is that of the Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, the French aristocrat and general who was a close friend of many American Founding Fathers including George Washington, Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson and fought in the Continental Army even before France officially entered the American Revolutionary War. He died in 1834 from natural causes at the age of 76, and an American flag always flies over his grave, courtesy of the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR).[4] He is buried next to his wife, Adrienne de La Fayette, whose sister, mother and grandmother were among those beheaded and thrown into the common pit. The soil that covers the grave is soil that Lafayette brought home to France from Bunker Hill in Charlestown, Boston – site of the Battle of Bunker Hill, one of the most prominent early battles of the American Revolutionary War; in 1825, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the battle, Lafayette had laid the cornerstone of the Bunker Hill Monument.

On 4 July 1917, three months after the United States entered World War I on the side of France and her Allies, U.S. Army Colonel Charles E. Stanton visited the General's tomb. Col. Stanton placed an American flag, uttering the famous phrase: "Lafayette, we are here."

America has joined forces with the Allied Powers, and what we have of blood and treasure are yours. Therefore it is that with loving pride we drape the colors in tribute of respect to this citizen of your great republic. And here and now, in the presence of the illustrious dead, we pledge our hearts and our honor in carrying this war to a successful issue. Lafayette, we are here.

Every Fourth of July, members of the DAR, the Society of the Cincinnati and U.S. embassy officials gather at Lafayette's tomb for a celebration.[6]

Jewish burials

In 1852, financier James Mayer de Rothschild built a hospital and hospice next door to the cemetery, at 76 rue de Picpus. Initially intended to treat Jewish patients, Rothschild Hospital was transformed into a general hospital open to all during World War I.[7]

During the Nazi occupation of Paris during World War II, French, Polish, and German Jews were rounded up and sent to the Drancy internment camp north of Paris.[8] Pregnant women, the seriously ill and children were sent to the Rothschild Hospital, which became an extension of the Drancy camp, under full guard and surrounded by barbed wire.[7]

Under the collusion of Vichy France with Nazi Germany, its patients who survived their illnesses were all deported to concentration camps. Of the 61,000 from Drancy sent to the camps, only 1,542 remained alive when the Allied forces liberated the camps in 1944.[9] There is a special plaque dedicated to their memory at Picpus Cemetery.

Notable Burials in the Picpus Cemetery

- Marguerite Louise d'Orléans (1645–1721), a Princess of France who became Grand Duchess of Tuscany, as the wife of Grand Duke Cosimo III de' Medici

- 1,306 victims of the Reign of terror between 14 June and 27 July 1794, including the following:

- Richard Mique (1728–1794), architect of the Hameau de la reine at the Palace of Versailles, guillotined 8 July 1794

- The 16 Discalced Carmelite women, Martyrs of Compiègne, guillotined on 17 July 1794 and buried in one of the two mass graves

- Henriette Anne Louise d'Aguesseau, Duchess of Noailles, Princess of Tingry (1737–1794), a French salon hostess and duchess, guillotined on 22 July 1794, along with her mother-in-law, Catherine de Cossé-Brissac duchesse de Noailles, and daughter, Anne Jeanne Baptiste Louise vicomtesse d'Ayen.

- Alexandre de Beauharnais (1760–1794), first husband of Josephine de Beauharnais and father of Eugène and Hortense, guillotined on 23 July 1794

- Frederick III, Prince of Salm-Kyrburg (1744–1794), German prince, colonel of the German troops, the battalion commander of the Fontaine-Grenelle, brother-in-law of the prince Anton Aloys, Prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen and brother of Princess Amalie Zephyrine, guillotined on 23 July 1794

- André Chénier (1762–1794), French poet, guillotined on 25 July 1794

- Jean-Antoine Roucher (1745–1794), poet, guillotined on 25 July 1794, as depicted in the engraving The last wagon

- Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (1757–1834), an important figure in both the French and American revolutions, co-author of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

- Marie Adrienne Françoise de Noailles, Marquise de La Fayette (1759–1807), French marchioness, wife of the Marquis de Lafayette

- Aimé Picquet du Boisguy (1776–1839), a notably young chouan general at the age of 19 during the French Revolution

- "G. Lenotre" (nom-de-plume of Louis Léon Théodore Gosselin) (1855–1935), French academician, historian and author of many works about the French Revolution, including Jardin de Picpus.

References

- Marie-Christine Pénin. "Cimetière de Picpus: cimetière révolutionnaire" (in French). Tombes & Sepultures. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Alfred Fierro (1988). Vie et histoire du XIIe arrondissement (in French). ISBN 978-2903118334.

- "Cimetière de Picpus" (in French). Office du Tourisme et des Congrès de Paris. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- "Picpus Cemetery". pariscemteries.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Charles E. Stanton Quotations, Biography

- "France et Etats-Unis: Lieux historiques" (in French). Embassy of the United States, Paris. Archived from the original on 6 December 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- Anne Landau. "The Rothschild Hospital". Northwestern University. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- "This Month in Holocaust History – December – Drancy". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- "Related Resources - Drancy". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cimetière de Picpus. |