Peter Cooper Hewitt

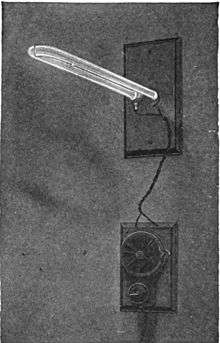

Peter Cooper Hewitt (May 5, 1861 – August 25, 1921) was an American electrical engineer and inventor, who invented the first mercury-vapor lamp in 1901.[1] Hewitt was issued U.S. Patent 682,692 on September 17, 1901.[2] In 1903, Hewitt created an improved version that possessed higher color qualities which eventually found widespread industrial use.[1]

Peter Cooper Hewitt | |

|---|---|

Peter Cooper Hewitt holding his mercury vapor rectifier | |

| Born | May 5, 1861 |

| Died | August 25, 1921 (aged 60) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Columbia University School of Mines |

| Known for | Arc discharge lamp, mercury-arc valve |

| Awards | Elliott Cresson Medal (1910) |

Early life

Hewitt was born in New York City, the son of New York City Mayor Abram Hewitt and the grandson of industrialist Peter Cooper. He was educated at the Stevens Institute of Technology and the Columbia University School of Mines.[3][4]

Career

In 1901 he invented and patented a mercury-vapor lamp; a gas-discharge lamp that used mercury vapor produced by passing current through liquid mercury. His first lamps had to be started by tilting the tube to make contact between the two electrodes and the liquid mercury; later he developed the inductive electrical ballast to start the tube. The efficiency was much higher than that of incandescent lamps, but the emitted light was of a bluish-green unpleasant color, which limited its practical use to specific professional areas, like photography, where the color was not an issue at a time where films were black and white. For space lighting use, the lamp was frequently augmented by a standard incandescent lamp.[5] The two together provided a more acceptable color. Later. in the 1930s. a fluorescent coating (phosphor) was added to the inside of the tube at General Electric, which produced more pleasing white light when it absorbed the ultraviolet light from the mercury. This was the fluorescent lamp, which is now one of the most widely used lamps in the world.

In 1902 Hewitt developed the mercury arc rectifier, the first rectifier that could convert alternating current power to direct current without mechanical means. It was widely used in electric railways, industry, electroplating, and high-voltage direct current (HVDC) power transmission. Although it was largely replaced by power semiconductor devices in the 1970s and 1980s, it is still used in some high power applications. In 1903, the degree of Honorary Doctorate of Science was conferred upon him by the Columbia University in recognition of his work. [6]

In 1907 he developed and tested an early hydrofoil. In 1916, Hewitt joined Elmer Sperry to develop the Hewitt-Sperry Automatic Airplane, one of the first successful precursors of the cruise missile.

Personal life

Hewitt married Lucy Bond Work (1861–1934),[7] a daughter of Franklin H. Work (1819–1911), a well-known stockbroker and protégé of Cornelius Vanderbilt, and his wife, Ellen Wood (1831–1877).[8] and sister of Frances Ellen Work.[9] He then fathered Ann Cooper Hewitt (July 31, 1914, Paris, France to February 09, 1956, Monterrey, Mexico) and later married her mother, Marion Jeanne Andrews,[10] the ex-wife of George William Childs McCarter,[11] Baron Robert Frederic Emile Regis D'Erlanger,[12] Dr. Peder Sather Bruguiere,[13][14] and Stewart Denning.[15] Hewitt later adopted Ann Cooper Hewitt, his illegitimate daughter.

Ann Cooper Hewitt

Maryon Jeanne Andrews Brugiere Denning Hewitt d’Erlanger McCarter sterilized her daughter, Ann Cooper Hewitt, to take her daughter's inheritance from Peter Cooper Hewitt's, her father's, estate, Maryon's ex-husband,[16][17] an inheritance dependent on the young woman having children.[18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29]

Further reading

- Baker, Ray Stannard (June 1903). "Peter Cooper Hewitt – Inventor; Three Great Achievements In Electrical Science". McClure's Magazine. XXI: 172–178. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- Burnett, Robert N. (March 1904). "Captains Of Industry, Part XXIII: Peter Cooper Hewitt". The Cosmopolitan. XXXVI (5): 556–558. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- Buttolph, L. J. (September 1920). "The Cooper Hewitt Lamp: Part I. Theory And Operation". General Electric Review. XXIII (9): 741–751. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- Buttolph, L. J. (October 1920). "The Cooper Hewitt Lamp: Part II. Development And Application". General Electric Review. XXIII (10): 858–865. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- Buttolph, L. J. (October 1920). "The Cooper Hewitt Quartz Lamp and Ultra-violet Light". General Electric Review. XXIII (11): 909–916. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- Hewitt, Peter Cooper (January 1902). "Electric Gas Lamps And Gas Electrical Resistance Phenomena". Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. XIX: 59–65. doi:10.1109/T-AIEE.1902.4763958. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- Pierce, George W. (February 1904). "On the Cooper Hewitt Mercury Interrupter". Daedalus. XXXIX (18): 389–415. doi:10.2307/20021910. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- Prout, Henry Goslee (1921). A Life Of George Westinghouse, Chapter XVI "Various Interests and Activities" (The Cooper Hewitt Lamp). New York: The Scribner Press. pp. 236–240.

- Squier, George Owen (1908). "The Present Status of Military Aeronautics. III. Hydromechanic Relations. Relative dynamic and buoyant support". Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution: 143–144. References Cooper Hewitt's hydrofoil work.

- (philadelphia, Franklin Institute; ), Pa (April 1903). "Notes and Comments. Cooper Hewitt Interrupter As An Aid In Wireless Telegraphy". Journal of the Franklin Institute. CLV (4): 315–316. doi:10.1016/s0016-0032(03)90227-4. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- "The March Of Radio: Did Peter Cooper Hewitt Discover The Grid?". Radio Broadcast. I (6): 460–461. October 1922. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- Sciences, National Institute of Social (October 1916). "The Awarding Of Medals: Presentation Medals". Journal of the National Institute of Social Sciences. II: 40–43. Retrieved 2009-08-07. References Cooper Hewitt's work with hydrofoils.

References

- "Peter Cooper Hewitt". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- "Method of Manufacturing Electric Lamps". United States Patent and Trademark Office.

- Shaw, Albert (June 1908). "Leading Articles Of The Month: Peter Cooper Hewitt, Inventor". The American Monthly Review of Reviews. XXVII (6): 724. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- University, Columbia (September 6, 1903). "Commencement Day". Columbia University Quarterly. V (4): 397–398. Retrieved 2009-08-07.

- The Boy Electrician by J.W. Simms, M.I.E.E (Page 280)

- "Obituary" (PDF). The Engineer: 236. 2 September 1921. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- "Lucy Bond Hewitt". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- Williamson, D. (1981) The Ancestry of Lady Diana Spencer In: Genealogist’s Magazine vol. 20 (no. 6) p. 192-199 and vol. 20 (no. 8) pp. 281–282.

- "WORK ESTATE ACCOUNTING.; Trustees of $15,000,000 Property Ask Advice on Lackawanna Stock". The New York Times. 2 June 1922. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- "Marion Jeanne Andrews". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- "George William Childs McCarter". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- "Baron Robert Frederic Emile Regis D'Erlanger". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- Francis Bruguière

- "Dr. Peder Sather Bruguiere". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- "Stewart Denning". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- Robinson, Jennifer. "AMERICAN EXPERIENCE: The Eugenics Crusade". kpbs.org. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- "California Eugenics". www.uvm.edu. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- Currell, Susan, and Christina Cogdell. 2006. Popular Eugenics. Athens: Ohio University Press.

- "The sordid story of the once-popular eugenics movement". Washington Post. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- Romeo Vitelli. "Sterilizing The Heiress". Providentia. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- Wendy, Kline. "A new deal for the child: Ann Cooper Hewitt and sterilization in the 1930s". repository.library.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- "EUGENICS IN CALIFORNIA, 1896-1945 by Joseph W. Sokolik". txstate.edu. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- Kline, Wendy (21 November 2005). Building a Better Race: Gender, Sexuality, and Eugenics from the Turn of the Century to the Baby Boom. University of California Press. p. 107. Retrieved 19 October 2018 – via Internet Archive.

Ann.

- "History". University of Cincinnati. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- Payne, G.S. (April 2010). "The Curious Case of Ann Cooper Hewitt" (PDF). History Magazine.

- Currell, Susan; Cogdell, Christina (19 October 2018). "Popular Eugenics: National Efficiency and American Mass Culture in the 1930s". Ohio University Press. Retrieved 19 October 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Kirsten Spicer. "A Nation of Imbeciles": The Human Betterment Foundation's Propaganda for Eugenics Practices in California. Chapman University". chapman.edu. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- "American Experience The Eugenics Crusade Premieres Tuesday, October 16 on PBS A Cautionary Tale About the Quest for Human Perfection". Archived from the original on 2018-10-19. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- Farley, Audrey Clare (8 July 2019) [First published 2019]. "The Curious Case of the Socialite Who Sterilized Her Daughter". Pocket, from Narratively. Archived from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

It was January of 1936, and heiress Ann Cooper Hewitt was suing her mother in a San Francisco court for $500,000 (equivalent to about $9,200,000 in 2019). The plaintiff claimed that her mother paid doctors to “unsex” her during an appendectomy in order to deprive her of an inheritance from her millionaire father’s estate. The defendant argued that she was merely protecting her daughter — and society — from the consequences of Ann becoming pregnant.

- "Unique Stunt by Whartons". The Moving Picture World. June 17, 1916. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

External links

- Works by or about Peter Cooper Hewitt at Internet Archive

- Andre Mohammed. "Peter Cooper Hewitt". ringwoodmanor.com. Archived from the original on 2003-10-22 – via archive.org.

This essay was written by a student at the New Jersey Institute of Technology and represents the only research done on this major inventor. The majority of the primary sources were found at the Cooper Archives in the Cooper Union Institute in Manhattan

- Peter Cooper Hewitt at Find a Grave