Sandungueo

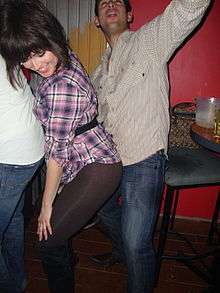

Sandungueo, also known as Perreo, is a style of dance and party music associated with reggaeton that emerged in the late 1980s in Puerto Rico. The dance resembles twerking. This style of dancing and music was created by DJ Blass, hence his Sandunguero Vol. 1 & 2 albums. [1] It is a dance that focuses on grinding, also known as perreo, with one partner facing the back of the other (usually male behind female).[2] This is also known as "booty dancing" or "grinding" in the United States of America.[3]

Origins

Sandungueo is a front-to-back dance, usually with a man facing the back of a woman. The moves focus on grinding and pelvic thrusts. They can be seen in music videos and night clubs.

It is a rare form of dance in which a woman usually takes the lead. Taking the lead in the sensual experience of both parties was appealing to some women. Drawing on research conducted in Cuba by ethnomusicologist Vincenzo Perna (see his book "Timba, the sound of the Cuban crisis", Ashgate 2005), author Jan Fairley suggested that this style of dance, along with other timba moves such as despelote, tembleque, and subasta de la cintura, in which the woman is both in control and the main focus of the dance, can be traced to the economic status of Cuba in the 1990s and to the choreographic forms of popular music dancing of that period, particularly in relation to Afro-Cuban timba. As the US Dollar (which functioned as a dual currency alongside the Cuban Peso until 2001) became more valuable, women changed their style of dance to be more visually appealing to men; in particular, to yumas ("foreigners"), who had dollars. This tension between use of the female body as both an objectified commodity and an active, self-created persuasive tool is one of the many paradoxes dembow dancing creates in Cuba.[4][5]

Controversy

Sandungueo was the subject of a national controversy in Puerto Rico as reggaeton music and the predominantly lower class culture it derived from became more popular and widely available. Velda González, a well known senator and public figure in Puerto Rico and Dominican Republic, led a campaign against reggaeton and specifically attacked the sandungueo style of dancing, which she marked as overtly erotic, sexually explicit, and degrading to women.[6][7]

Sandungueo has also been much criticized in Cuba. Part of the criticism may be due to its association with reggaeton, which, while very popular in Cuba, has also been heavily criticized for being degrading to women.[5] Perreo has been seen as a departure from classical front-to-front dancing (salsa etc.) to back-to-front dancing. Some Cuban dancers argue that this puts women in control. Others have argued that it is un-Cuban, and the Cuban government seemed to agree when it banned reggaeton (which was sometimes referred to as Cubaton)[8] in Cuba in 2012.[9][10][11]

A remix called "Perreo intenso" was one of the popular songs during the Telegramgate protests that led to the Puerto Rican governor, Ricardo Rosselló's renouncing his position.

An analysis of Puerto Rico's discourse shows politicians and reggaeton artists denouncing each other's corruption and immoral behavior, respectively.[12] SWAT teams on hand, a perreo intenso (transl. an intense perreo) was going on in front of the governor's mansion when he announced his resignation.[13]

Doble Paso

Doble Paso is a form of Sandungueo or Perreo in which the rhythm and the tempo of the songs is faster, resulting in a dance form which is more sexually explicit and intense. Doble Paso is mainly emerging and gaining popularity among Puerto Rican teens; thus causing parents and the conservative community to criticize this form of dance.

References

- "Q&A with The Reggaeton producer DJ Blass from Puerto Rico". July 3, 2014.

- "Reggaeton Nation". December 19, 2007.

- Andrea Hidalgo (2005-06-02). "Perreo causes Controversy for Reggaeton". Reggaetonline.net.

- Fairley, Jan. (2008) "How To Make Love With Your Clothes On: Dancing Reggaeton and Gender In Cuba". In Reading Reggaeton (forthcoming, Duke University Press).

- Fairley, Jan. "Como hacer el amor con ropa (How to Make Love with your Clothes On)". Institute of Popular Music. University of Liverpool.

- Frances Negrón-Muntaner and Raquel Z. Rivera, "Reggaeton Nation" (17 December 2007)

- Rivera-Rideau, P.R. (2015). Remixing Reggaetón: The Cultural Politics of Race in Puerto Rico. Duke University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8223-7525-8. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- "Salsamania Magazine". docplayer.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Wagner, David (December 7, 2012). "Cuba Banned Reggaeton and People Are Surprisingly OK with That". The Atlantic.

- "Reggaeton in Cuba". Retrieved 2008-02-08.

- Baker, Geoff. "The Politics of Dancing: Reggaeton and Rap in Havana, Cuba". Royal Holloway. University of London.

- "DJ Sessions: The Music That Helped Oust Puerto Rico's Governor". www.wbur.org.

- Jackson, Jhoni; Exposito, Susan (July 25, 2019). "As Puerto Rico Governor Resigns, San Juan Parties the Night Away". Rolling Stone Magazine.