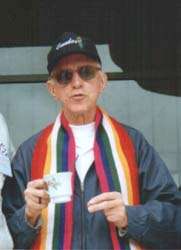

Pedro Casaldáliga

Pedro Casaldàliga i Plà CMF (born 16 February 1928) is a Catalan-born prelate of the Catholic Church who led the Territorial Prelature of São Félix, Brazil, from 1970 to 2005. A bishop since 1971, he is one of the best known exponents of liberation theology. He has received numerous awards, including the International Catalonia Prize in 2006. He has been a forceful advocate in support of indigenous peoples and has published several volumes of poetry.

Biography

He was born Pere Casaldàliga on 16 February 1928 in Balsareny, Catalonia, Spain, and grew up on his family's cattle ranch.[1] He joined the Claretians and was ordained a priest in Barcelona on 31 May 1952.

He moved to Brazil as a missionary in 1968.[2]

On 27 April 1970, Pope Paul VI named him Apostolic Administrator of the Territorial Prelature of São Félix. On 27 August 1971, Pope Paul named him prelate of that jurisdiction and titular bishop of Altava.[3] He received his episcopal consecration on 23 October from Fernando Gomes dos Santos, Archbishop of Goiânia.

In the 1970s, the military regime ruling Brazil tried without success to force him to leave the country. His advocacy for indigenous peoples and peasants resulted in repeated death threats, and in 1976 a priest was killed standing alongside him at a march protesting the mistreatment of female prisoners.[2] In the 1980s he refused to make the required ad limina visits to Rome that bishops normally make every five years. He said he feared not being able to re-enter Brazil and said "The visits were bureaucratic and formal and did not lead to proper dialogue."[2]

In 1986, he founded a pilgrimage, Romería de los Mártires, held every five years.[4] It centers on the site where Jesuit João Bosco Bernier was killed at Casaldáliga's side on 11 October 1976, the Sanctuary of the Martyrs of the "Caminhada".[5]

In June 1988, as part of a Vatican effort to place restrictions on the liberation theology movement and following its 1985 silencing of Brazilian theologian Leonardo Boff, Casaldáliga was called to Rome to be examined by Cardinals Joseph Ratzinger and Bernadin Gantin on his theological writings and pastoral activity. The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) and the Congregation of Bishops then produced statement for him to sign as an acknowledgment of his errors. It promised he would not add political content to processions, accept restrictions on his theological work, and only say Mass or preach outside of Brazil, especially in Nicaragua, with permission from the local bishop. He did not sign it. He summarized his views: "My attitude is a reflection of the view of the church in many regions of the world. I have criticized the Curia over the way bishops are chosen, over the minimal space given to women, over its distrust of liberation theology and bishops' conferences, over its excessive centralism. This does not mean a break with Rome. Within the family of the church and through dialogue, we need to open up more space."[2]

Pope John Paul II accepted his resignation on 2 February 2005.[6] Anticipating the appointment of his successor, he objected that it would happen without the people of the prelature being consulted.[7] In retirement he continued to live in São Félix do Araguaia,[8][lower-alpha 1] and work as an ordinary priest under his successors.[4]

He was awarded the International Catalonia Prize in 2006.[9]

When the CDF criticized the work of theologian Jon Sobrino of El Salvador in 2007, Casaldáliga responded with an open letter asking that the Church confirm its “real commitment to the service of God’s poor" and acknowledge "the link between faith and politics".[10]

He was awarded Brazil's Order of Cultural Merit in 2010.

He has had Parkinson's disease since at least 2012;[8] he refers to it as "Brother Parkinson".[4]

Notes

- As of 2018, the town had a population of 10,500. The nearest airport in Cuiabá, capital of the state of Mato Grosso, is reached by a 16-hour trip on dirt roads.[4]

Select writings

- África De Colores. Promoción Popular Cristiana, 1961.

- Creio na Justiça e na Esperança. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 1977.

- Proclama del justo sufriente: relatos y poemas brasilero (con Frédy Kunz y Pedro Terra). Centro de Estudios y Publicaciones, 1979.

- Experiencia de Dios y Pasión por el Pueblo. Santander: Sal Terrae, 1983. ISBN 84-293-0670-6

- Comunidade, ecumenismo e libertação'. São Paulo: EDUC, 1983.

- Nicaragua, Combate y Profecía. San José de Costa Rica: DEI, 1987. ISBN 99-779-0439-1

- El vuelo del quetzal: espiritualidad en Centroamérica. Maíz Nuestro, 1988.

- Leonidas Proaño: El Obispo de Los Pobres (con Francisco Enríquez). Quito: El Conejo, Corporación Editorial, 1989. ISBN 9978-87-009-1

- Espiritualidad de la Liberación (con José Mª Vigil). Santander: Sal Terrae, 1992. ISBN 84-293-1076-2

- Sonetos neobíblicos, precisamente. Musa, Nueva Utopía, 1996.

- Ameríndia, morte e vida (con Pedro Terra). Petrópolis: Paulus, 1997.

- Murais da libertação (con Cerezo Barredo). São Paulo: Loyola, 2005.

- Orações da caminhada (con Pedro Terra). Verus Editora, 2005.

- Versos adversos: antologia (con Enio Squeff). Editora Fundação Perseu Abramo, 2006.

- Martírio do padre João Bosco Penido Burnier. São Paulo: Loyola, 2006. ISBN 85-15-03238-4

References

- "Casaldáliga, Pedro (1928–)". Encyclopedia.com. 14 October 2019. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Riding, Alan (27 September 1988). "Vatican Acts To Discipline Cleric in Brazil". New York Times. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Acta Apostolicae Sedis (PDF). LXIII. 1971. p. 782.

- Avendaño, Tom C. (16 February 2018). "Pedro Casaldáliga: 90 años de vida, 50 del 'obispo del pueblo'". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Modino, Luis Miguel (14 July 2016). "La Romería de los Mártires de la "Caminhada", este fin de semana". Periodista Digital (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- "Rinunce e Nomine, 02.02.2005" (Press release) (in Italian). Holy See Press Office. 2 February 2005. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Arias, Juan (16 January 2005). "Casaldáliga reta a Roma". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- "Pere Casaldàliga, evacuado de su casa de São Félix por amenazas de muerte". Periodista Digital (in Spanish). 8 December 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- "2006 Pere Casaldàliga". Generalitat de Catalunya: Department de la Presidència. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Rohter, Larry (7 May 2007). "As Pope Heads to Brazil, a Rival Theology Persists". New York Times. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- Additional sources

- Escribano, Francesc (2002). Descalzo sobre la tierra roja: vida del obispo Pere Casaldàliga (in Catalan). Barcelona: Ediciones Península. ISBN 84-8307-453-2.

- Marzec, Zofia (2005). Pedro de los pobres (in Spanish). Madrid: Nueva Utopía. ISBN 84-96146-13-8.

- Soler i Canals, Josep Maria; Serra, Sebastià (2013). Pere Casaldàliga (in Catalan). L'Abadia de Montserrat. ISBN 978-84-9883-631-8.

- Guerrero, Joan (2016). Casaldàliga: la seva gent i les seves causes = su gente y sus causas = sua gente e suas causas. Claret. ISBN 978-84-9846-988-2.

External links

- Barefoot on Red Soil on IMDb

- Catholic Hierarchy: Bishop Pedro Casaldáliga Plá, C.M.F. [self-published]