Pedagogy of the Oppressed

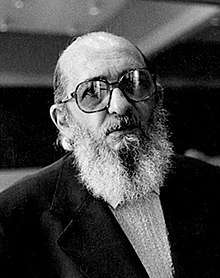

Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Portuguese: Pedagogia do Oprimido), is a book written by Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, first written in Portuguese in 1968. It was first published in English in 1970, in a translation by Myra Ramos.[1] The book is considered one of the foundational texts of critical pedagogy, and proposes a pedagogy with a new relationship between teacher, student, and society.

.jpg) Spanish edition, 1968 | |

| Author | Paulo Freire |

|---|---|

| Original title | Pedagogia do Oprimido |

| Translator | Myra Ramos |

| Country | Brazil |

| Language | Portuguese |

| Subject | Pedagogy |

| Publisher | Herder and Herder |

Published in English | 1970 |

| ISBN | 9780826412768 |

| 370.115 | |

| LC Class | LB880 .F73 |

| Critical pedagogy |

|---|

| Major works |

| Theorists |

| Pedagogy |

|

| Concepts |

| Related |

Dedicated to the oppressed and based on his own experience helping Brazilian adults to read and write, Freire includes a detailed Marxist class analysis in his exploration of the relationship between the colonizer and the colonized. In the book, Freire calls traditional pedagogy the "banking model of education" because it treats the student as an empty vessel to be filled with knowledge, like a piggy bank. He argues that pedagogy should instead treat the learner as a co-creator of knowledge.[2]

The book has sold over 750,000 copies worldwide.[3]

Synopsis

Freire organizes the Pedagogy of the Oppressed into 4 chapters and a preface.

Freire uses the preface to provide a background to his work and the potential downsides. He explains that this came from his experience as a teacher in Brazil and when he was in political exile. In this time, he noticed that his students had an unconscious fear of freedom, or rather: a fear of changing the way the world is. Freire then outlines the likely criticisms his book will face. Furthermore, his audience should be radicals- people that see the world as changing and fluid, and he admits his argument will most likely be missing things. Basing his method of finding freedom on the poor and middle class’s experience with education, Freire states that his ideas are rooted in reality- not purely theoretical

Freire utilizes chapter 1 to explain why this pedagogy is necessary. Describing humankind’s central problem as affirming one’s identity as human, Freire states that everyone strives for this, but oppression interrupts many people on this journey. These halts are termed dehumanization. Dehumanization, when individuals become objectified, occurs due to injustice, exploitation, and oppression. The Pedagogy of the Oppressed is Freire’s attempt to help the oppressed fight back to regain their lost humanity and achieve full humanization. There exist many steps for this process. First of which, is for the oppressed to understand what humanization truly is. It is easy for the oppressed to fight to become polar opposites of what they currently are. However, this just makes them the oppressors and starts the cycle all over again. To be fully human again, they must identify the oppressors. They must identify them and work together to seek liberation. The next step in liberation is to understand what the goal of the oppressors is. Oppressors are purely materialistic. They see humans as objects and by suppressing individuals, they are able to own these humans. While they may not be consciously putting down the oppressed, they value ownership over humanity, essentially dehumanizing themselves. This is important to realize as the goal of the oppressed is to not only gain power. It is to allow all individuals to become fully human so that no oppression can exist. Freire states that once the oppressed understand their own oppression and discovers their oppressors, the next step is dialogue, or discussion with others to reach the goal of humanization. Freire also highlights other events on this journey that the oppressed must undertake. There are many situations that the oppressed must keep wary about. For example, they must be aware of the oppressors trying to help the oppressed. These people are deemed falsely generous, and in order to help the oppressed, one must first fully become the oppressed, mentally and environmentally. Only the oppressed can allow humanity to become fully human with no instances of objectification.

In chapter 2, Freire outlines his theories of education. The first discussed is the banking model of education. He believes the fundamental nature of education is to be narrative. There is one individual reciting facts and ideas (the teacher) and others that just listen and memorize everything (the students). There is no connection with their real life, resulting in a very passive learning style. This form of education is termed the banking model of education. The banking model is very closely linked with oppression. It is built on the fact that the teacher knows all, and there exist inferiors that must just accept what they are told. They are not allowed to question the world or their teachers. This lack of freedom highlights the comparisons between the banking model of education and oppression. Freire urges the dismissal of the banking model of education and the adoption of the problem-posing model. This model encourages a discussion between teacher and student. It fades the line between the two as everyone learns alongside each other, creating equality and the lack of oppression. There are many ways the banking model of education aligns with oppression. Essentially, it dehumanizes the student. If they are raised to learn to be blank slates molded by the teacher, they will never be able to question the world if they need to. This form of education encourages them to just accept what is thrust upon them and accept that as correct. It makes the first step of humanization very difficult. If they are trained to be passive listeners, they will never be able to come to the realization that there even exists oppressors.

Chapter 3 is used to expand on Freire’s idea of dialogue. He first explains the importance of words, and that they must reflect both action and reflection. Dialogue is an understanding between different people and it is an act of love, humility, and faith. It provides others the complete independence to experience the world and name it how they see it. Freire explains that educators shape how students see the world and history. They must use language with the point of view of the students in mind. They must allow “thematic investigation:” the discovery of different relevant problems and ideas for different periods of time. This ability is the difference between animals and humans. Animals are stuck in the present unlike humans who understand history and use it to shape the present. Freire explains that the oppressed usually are not able to see the problems of their own time, and oppressors feed on this ignorance. Freire also presses the importance of educators not becoming oppressors and not objectifying their students. Educators and students must work as a team to find the problems of history and the present.

Freire lays out the process of how the oppressed can truly liberate themselves in chapter 4. He explains the methods used by oppressors to suppress humanity and the actions the oppressed can undertake in order to liberate humanity. The tools the oppressed use are termed, “anti-dialogical actions,” and the ways the oppressed can overcome them are, “dialogical actions.” The four anti-dialogical actions include conquest, manipulation, divide and rule, and cultural invasion. The four dialogical actions, on the other hand, are unity, compassion, organization, and cultural synthesis.[2]

Spread

The book was first published in Spanish translation in 1968. An English version was published in 1970, and the original Portuguese in 1972.

Since the publication of the English edition in 1970, Pedagogy of the Oppressed has been widely adopted in America's teacher-training programs. A 2003 study by David Steiner and Susan Rozen determined that Pedagogy of the Oppressed was frequently assigned at top education schools.[4]

Influences

The work was strongly influenced by Frantz Fanon and Karl Marx.

Freire's work was one inspiration for Augusto Boal's Theatre of the Oppressed. [5]

Reception

Pedagogy of the Oppressed is considered groundbreaking because it is one of the first pieces of literature to challenge the education system.[6]

Donaldo Macedo, a former colleague of Freire and University of Massachusetts Boston professor, calls Pedagogy of the Oppressed a revolutionary text, and people in totalitarian states risk punishment reading it.[2] During the South African anti-apartheid struggle, the book was banned and kept clandestine. Ad-hoc copies of the book were distributed underground as part of the "ideological weaponry" of various revolutionary groups like the Black Consciousness Movement.[7]

According to Diana Coben, Freire was criticized by feminists for use of sexist language in his early work, and some text in Pedagogy of the Oppressed was revised for the 1995 edition to avoid sexism.[8]

In 2006, Pedagogy of the Oppressed came under criticism over its use by the Mexican American Studies Department Program at Tucson High School. In 2010, the Arizona State Legislature passed House Bill 2281, enabling the Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction to restrict state funding to public schools with ethnic studies programs, effectively banning the program. Tom Horne, who was Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction at the time, criticized the program for "teaching students that they are oppressed."[9] The book was among seven titles officially confiscated from Mexican American Studies classrooms, sometimes in front of students, by the Tuscon Unified School District after the passing of HB 2281.[10]

In his article for the conservative City Journal, Sol Stern writes that Pedagogy of the Oppressed ignores the traditional touchstones of Western education (e.g., Rousseau, John Dewey, or Maria Montessori) and contains virtually none of the information typically found in traditional teacher education (e.g., no discussion of curriculum, testing, or age-appropriate learning). To the contrary, Freire rejects traditional education as "official knowledge" that intends to oppress.[11] Stern also writes that heirs to Freire's ideas have taken them to mean that since all education is political, "leftist math teachers who care about the oppressed have a right, indeed a duty, to use a pedagogy that, in Freire's words, 'does not conceal—in fact, which proclaims—its own political character.'"[12]

A 2019 article in Spiked (magazine), a British Internet magazine focusing on politics, culture and society claims that, "In 2016, the Open Syllabus Project catalogued the 100 most requested titles on its service by English-speaking universities: the only Brazilian on its list was Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed."[13]

See also

References

- "About Pedagogy of the Oppressed". Archived from the original on 2011-10-12. Retrieved 2011-06-01.

- Freire, Paulo (September 2000). Pedagogy of the Oppressed (30th anniversary ed.). New York: Bloomsbury. p. 16. ISBN 9780826412768. OCLC 43929806.

- Publisher's Foreword in Freire, Paulo (2000). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum, p. 9.

- "Skewed Perspective - Education Next". Education Next. 2009-10-20. Retrieved 2017-03-05.

- Augusto Boal (1993). Theater of the Oppressed. New York: Theatre Communications Group. ISBN 0-930452-49-6, p 120

- "PAULO FREIRE | Encyclopedia of Education and Human Development - Credo Reference". search.credoreference.com. Retrieved 2020-02-19.

- Archie Dick (2010) "Librarians and Readers in the South African Anti-Apartheid Struggle", public lecture given in Tampere Main Library, August 19, 2010.

- Coben, Diana (April 1998). Radical Heroes: Gramsci, Freire and the Poitics of Adult Education. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 0815318987. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Lundholm, Nicholas (2011). "Cutting Class: Why Arizona's Ethnic Studies Ban Won't Ban Ethnic Studies" (PDF). Arizona Law Review. 53: 1041–1088.

- Rodriguez, Roberto Cintli (18 January 2012). "Arizona's 'banned' Mexican American books". The Guardian.

- Stern, Sol. "Pedagogy of the Oppressor", City Journal, Spring 2009, Vol. 19, no. 2

- Stern, Sol. "'The Ed Schools' Latest—and Worst—Humbug", City Journal, Spring 2006, Vol. 16, No. 3.

- GARCIA, R T. "The culture war over Brazil's leading intellectual". spiked-online.com. Retrieved 13 May 2019.

Bibliography

- Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum, 2007.

- Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th Anniversary ed. New York: Continuum, 2006.

- Rich Gibson, The Frozen Dialectics of Paulo Freire, in NeoLiberalism and Education Reform, Hampton Press, 2006.

External links

- A detailed chapter by chapter summary

- Noam Chomsky, Howard Gardner, and Bruno della Chiesa discussion about the book's impact and relevance to education today at the Askwith Forum commemorated the 45th anniversary of the publication of the book.

- English translation of the book