Pavel Schilling

Baron Pavel Lvovitch Schilling (1786–1837), also known as Paul Schilling, was a Russian military officer and diplomat of Baltic German origin. The majority of his career was spent working for the imperial Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs as a language officer at the Russian embassy in Munich. As a military officer, he took part in the War of the Sixth Coalition against Napoleon. In his later career, he was transferred to the Asian department of the ministry and undertook a tour of Mongolia to collect ancient manuscripts.

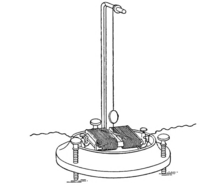

Schilling is best known for his pioneering work in electrical telegraphy, which he undertook at his own initiative. While he was in Munich, he worked with Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring who was developing an electrochemical telegraph. Schilling developed the first electromagnetic telegraph that was of practical use. Schilling's design was a needle telegraph using magnetised needles suspended by a thread over a current-carrying coil. His design also greatly reduced the number of wires compared to Sömmerring's system by the use of binary coding. Tsar Nicholas I planned to install Schilling's telegraph on a link to Kronstadt, but cancelled the project after Schilling died.

Other technological interests of Schilling included lithography, remote detonation of explosives, and submarine cables.

Early life

Baron Pavel Lvovitch Schilling von Cannstadt was born in Reval (now Tallinn), Estonia, on 16 April 1786 (N.S.).[1] He was an ethnic German, but a Russian citizen as Estonia was then part of the Russian Empire. His father was L. F. Schilling, commander of the 23rd Nizovsk infantry regiment, and Pavel was the eldest of four children.[2] He was expected to follow a military career like his father, so he was sent to First Cadet Corps at the age of eleven. On graduating as a subaltern, he was posted to a unit commanded by F. I. Schubert and assigned cartographical surveying duties.[3]

Diplomatic career

Family circumstances obliged Schilling to resign his commission in 1803. He then joined the foreign service as a language officer.[4] He was an attaché to the Russian embassy in Munich from 1809 to 1811.[5] He first became interested in electrical science while he was in Munich through contact with Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring who was developing an electrical telegraph.[6] His duties as a diplomat were light. He was left him with time on his hands, much of which he spent with Sömmerring,[7] and he brought many Russian dignitaries to see Sömmerring's apparatus.[8]

When war threatened between France and Russia, Schilling put his mind to applying his electrical knowledge to military purposes. He devised a water resistant conducting wire that could be laid in wet earth or through rivers. It consisted of a copper wire insulated with a mixture of India-rubber and varnish. Schilling had in mind the military use of telegraphy in the field for this invention. He also thought it would be useful for exploding mines at a distance.[9] Schilling became very excitable about the latter idea. Sömmerring wrote in his diary "Schilling is quite childish about his electro-conducting cord."[10]

Napoleonic wars

Schilling, along with all Russian diplomats in Germany, was recalled to St. Petersburg in 1812 as the impending French invasion of Russia loomed.[11] There he continued his work on mine detonation. He used an electric spark across charcoal points (electrodes ending in a sharp point) connected to the end of his cable. He experimentally set off explosions across the Neva River and later, during the occupation of Paris in 1814, across the Seine.[12] He once took the end of an igniter cable into the Tsar's tent while on campaign and invited him to touch the wires together. The resulting distant explosion surprised everyone and earned Schilling a round of applause.[13]

Schilling requested a military position and on 6 September 1813 he was posted to the 3rd Sumsk dragoons with the rank of staff captain.[14][note 1] He remained in the regiment throughout the War of the Sixth Coalition and saw action at Arcis-sur-Aube (20–21 February 1814), Fere-Champenoise (25 February), Bar-sur-Aube (27 February), and the final close on Paris (30 March).[15] He was awarded a military medal and a sword inscribed "for valour".[16]

Return to diplomacy

Schilling returned to his duties in Munich in 1815. He continued to take an interest in electricity, and also in lithography, a new method of printing which he wished to introduce into Russia.[17] He met with Alois Senefelder, the inventor of the lithographic process, in 1816,[18] and later founded a large lithographic printing establishment in Russia after he was appointed Director of Lithography at the ministry.[19] Schilling set up an electrical engineering workshop in the Peter and Paul Fortress. He recruited Moritz von Jacobi from Dorpat University to act as his assistant there.[20] In March 1818, Schilling was made a Knight of the Order of Saint Anna.[21]

The government wished to strengthen ties with eastern neighbours. Schilling was transferred to the Asian Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as part of this movement.[22] In 1828 Schilling was made a State Councillor and he became a corresponding member of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences.[23] In May 1830,[24] he was sent on a two-year mission to Mongolia (then part of China),[25] tasked with searching for rare manuscripts.[26] He returned to St. Petersburg in March 1832,[27] bringing with him a valuable collection of documents in Chinese, Tibetan, Mongolian and other languages. These were deposited in the Imperial Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg.[28] Some of these documents were obtained in exchange for a demonstration of the small telegraph apparatus Schilling had carried with him.[29] Back in St. Petersburg, Schilling returned to developing a telegraph. There were plans to put it into service, but Schilling died before these could be completed.[30]

Telegraphy

Schilling first became involved in telegraphy while he was in Munich. He assisted Samuel Thomas von Sömmerring with his experiments with an electrochemical telegraph. This form of telegraph uses electricity to cause a chemical reaction at the far end, such as bubbles forming in a glass tube of acid. After returning to St. Petersburg he conducted his own experiments with this type of telegraph. He demonstrated his version to Tsar Alexander I in 1812, but Alexander I declined to take it up. The Tsar went even further, and forbade all research and publications on electrical telegraphy as a revolutionary idea.[31]

When Schilling learned of Hans Christian Ørsted's discovery in 1820 that electric current could deflect compass needles, he decided to switch investigation into needle telegraphs, that is, telegraphs that used Ørsted's principle. A new Tsar, Nicholas I, ascended the throne in 1825. He was more receptive to new technology than Alexander I.[32] Schilling used from one to six needles in various demonstrations to represent letters of the alphabet or other information.[33] He took a single-needle instrument with him for demonstration purposes on his journey to Mongolia.[34] When he returned, Schilling used a binary code on his telegraph with multiple needles, inspired by I Ching hexagrams which he had become familiar with in Mongolia. These hexagrams are figures used in divination, each of which consist of a figure of six stacked lines. Each line can be solid or broken, two binary states, leading to a total of 64 figures. The six units of the I Ching fitted in perfectly with the six needles he needed to code the Russian alphabet.[35] This was the first use of binary coding in telecommunications, predating the Baudot code by several decades.[36]

1832 demonstration

On 21 October 1832 (O.S.), Schilling set up a demonstration of his six-needle telegraph between two rooms in his apartment building about 100 metres apart.[note 2] To get the space to demonstrate a credible distance, he hired the entire floor of the building and ran a mile and a half of wire around the building. The demonstration was so popular that it stayed open until the Christmas break. Notable visitors included Nicholas I (who had already seen an earlier version in April 1830),[37] Moritz von Jacobi, Alexander von Benckendorff, and Grand Duke Michael Pavlovich. A ten-word message in French was dictated by the Tsar and successfully sent over the apparatus.[38][note 3] Alexander von Humboldt, after seeing Schilling's telegraph demonstrated in Berlin, recommended to the Tsar that a telegraph should be built in Russia.[39]

In May 1835 he began a tour of Europe demonstrating a one-needle instrument. He conducted experiments in Vienna with other scientists, including an investigation into the relative merits of rooftop and buried cables. The buried cable was not successful because his thin India rubber and varnish insulation was inadequate. In September he was at a meeting in Bonn where Georg Wilhelm Muncke saw the instrument. Muncke had a copy made for use in his lectures.[40] In 1835, Schilling demonstrated a five-needle telegraph to the German Physical Society in Frankfurt. By the time Schilling returned to Russia, his telegraph was well known throughout Europe and was frequently discussed in the scientific literature. In September 1836, the British government offered to buy the rights to the telegraph but Schilling declined, wishing to use it to pursue telegraphy in Russia.[41]

Planned installation

In 1836, Nicholas I created a commission of inquiry to advise on installation of Schilling's telegraph between Kronstadt, an important naval base, and Peterhof Palace.[42] Prince Alexander Menshikov, the Minister of Marine,[43] was appointed president of the commission.[44] Schilling offered two schemes to the commission. One was to lay a submarine cable across the Gulf of Finland. The wires were to be insulated with varnished silk, bound together, and the whole assembly tarred. The other option was to suspend the wires on poles along the Peterhof Road.[45]

An experimental line was set up in the Admiralty building running from a room near the grand entrance to Menshikov's study in the northwest corner with telegraph equipment at each end. The line was partly overground and partly submerged in the canal. Menshikov submitted a favourable report and Nicholas I issued a decree in May 1837 ordering the installation of a submarine cable to Kronstadt.[46] Schilling took the project as far as ordering the submarine cable from a rope factory in St. Petersburg,[47] but he died on 6 August (N.S.),[48][note 4] and the project was subsequently cancelled.[49]

Single-wire code

Schilling is sometimes credited with being the first to devise a code for a single-wire telegraph, but there is some doubt about how many needles he used and at what dates.[50] It may be that Schilling used a single-needle-only setup on demonstrations around Europe merely for ease of transport, or it may have been a later design inspired by the Gauss and Weber telegraph, in which case he would not have been the first.[51] The code alleged to have been used with this telegraph can be traced to Alfred Vail,[52] but the variable-length code (like Morse code) given by Vail is merely shown as an example of how it could be used.[53] In any case, two-element signalling alphabets predate any form of electrical telegraphy by some time.[54] According to Hubbard, it is more likely that Schilling used the same code as used on the six-needle telegraph, but with the bits sent serially instead of in parallel.[55]

Automatic recording

Schilling looked into the possibility of automatic recording of telegraph signals, but could not make it work due to the complexity of the device. His electrical engineering successor, Jacobi, succeeded in doing this in 1841 on a telegraph line from the Winter Palace to the General Staff Headquarters.[56]

Legacy

The Schilling needle telegraph, as such, was never used, but it is partly the ancestor of the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph, a system widely used in the United Kingdom and British Empire in the nineteenth century, and some instruments remained in use well into the twentieth century.[58] Schilling's demonstration in Frankfurt was attended by Georg Wilhelm Muncke who subsequently had an exact copy of Schilling's apparatus made. Muncke used this for demonstrations in lectures. One of these lectures was attended by William Fothergill Cooke, who was inspired to build a version of Schilling's telegraph of his own, although he did not realise that the instrument he saw was due to Schilling.[59] He abandoned this method for practical use in favour of electromagnetic clockwork solutions for a while, apparently believing that needle telegraphs always required multiple wires.[60] That Schilling's method of suspending the needle by a thread horizontally was not very convenient was also an influence. This changed when he partnered with Charles Wheatstone and the telegraph they then built together was a multiple-needle telegraph, but with a rather more robust mounting based on the galvanometer of Macedonio Melloni.[61] There is no evidence for the claim sometimes advanced that Wheatstone also lectured with a copy of Schilling's telegraph,[62] although he certainly knew about it and lectured on its implications.[63]

Schilling's telegraph of 1832 is currently displayed in the telegraph collection of the A.S. Popov Central Museum of Communications.[64] The instrument was previously on exhibition at the Paris Electrical Exhibition of 1881.[65] His contributions to electrical telegraphy were named an IEEE Milestone in 2009.[66] The building housing his apartment in St. Petersburg, then known as Ofrosimova's house, but now 7 Marsovue Pole, has a memorial plaque, placed in 1886 to mark the centennial of his birth.[67]

Notes

- Hamel gives the rank as Stabsrittmeister, literally, "cavalry chief of staff", which is a rank between Rittmeister (equivalent to captain) and Premierleutnant (1st lieutenant). Hamel describes Schilling's regiment as the Secumsky regiment of Hussars, but this may just be a variant translation rather than a different regiment.

- Sources disagree over whether the 1832 demonstration had six signal needles or one. A one-needle telegraph could replace a six-needle telegraph by sending the digits of the code serially instead of in parallel. Examples of Schilling's six-needle telegraph are in museums in Munich and St. Petersburg, but these are likely not originals. They appear to have been built much later (in the 1880s) for display at exhibitions (Hubbard, p. 13).

- Some sources (Hubbard, p. 13, Dudley, p. 103) place the demonstration to the Tsar in Berlin. This seems less likely and may be an error. If it was not, there must have been two demonstrations.

- Huurdeman gives the date of Schilling's death as 25 July, but this would seem to be a Julian calendar date.

References

- Yarotsky

- Yarotsky, p. 709

- Yarotsky, pp. 709–710

- Yarotsky, p. 710

- Huurdeman, p. 54

- Huurdeman, p. 54

- Hubbard, p. 11

- Hamel, p. 13

- Fahie, pp. 308–309

- Hamel, p. 21

- Huurdeman, p. 54

- Fahie, pp. 308–309

- Hamel, p. 42

- Yarotsky, p. 710

- Hamel, p. 22

- Yarotsky, p. 710

- Fahie, p. 309

- Hamel, p. 27

-

Hamel, p. 41

- Yarotsky, p. 710

- Yarotsky, p. 713

- Hamel, p. 31

- Yarotsky, p. 710

- Artemenko

- Artemenko

- Huurdeman, p. 54

- Artemenko

- Artemenko

- Hamel, p. 42

- Hamel, pp. 42–43

- Huurdeman, p. 54

- Huurdeman, p. 54

- Huurdeman, p. 54

-

Fahie, p. 309

- Huurdeman, p. 54

- Fahie, p. 315

- Artemenko

- Garratt, p. 273

- Hamel, p. 41

-

Artemenko

- Yarotsky, p. 709

- Hubbard, p. 13

- Huurdeman, p. 54

- Siegert, p. 175

- Fahie, p. 316

- Fahie, p. 317

- Huurdeman, p. 54

- Yarotsky, p. 713

- Fahie, p. 318

- Fahie, pp. 317–318

- Fahie, pp. 318–319

- Hamel, p. 67

- Fahie, p. 319

- Huurdeman, p. 54

- Shaffner, pp. 135–137

- Vail, p. 155

- Fahie, p. 311

- Vail, p. 156

- Fahie, p. 311

- Hubbard, p. 13

- Yarotsky, p. 713

-

Michel stamp catalogue, 5200

- Scott stamp catalogue, 5069

- Huurdeman, pages 67–69

- Hubbard, pp. 14, 23

- Shaffner, p. 187

- Hubbard, pp. 39, 119

- Hubbard, p. 14

- Dudley, p. 103

- Artemenko

- Fahie, p. 313

- "Milestones:Shilling's Pioneering Contribution to Practical Telegraphy, 1828-1837". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Yarotsky, p. 709

Bibliography

- Artemenko, Roman, "Павел Шиллинг - изобретатель электромагнитного телеграфа" ["Pavel Schilling - inventor of the electromagnetic telegraph"], ITWeek, vol. 3, iss. 321, 29 January 2002 (in Russian).

- Bermel, Neil, Linguistic Authority, Language Ideology, and Metaphor: The Czech Orthography Wars, Walter de Gruyter, 2008 ISBN 3110197669.

- Dudley, Leonard, Mothers of Innovation: How Expanding Social Networks Gave Birth to the Industrial Revolution, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012 ISBN 1443843121.

- Fahie, John Joseph, A History of Electric Telegraphy, to the Year 1837, London: E. & F.N. Spon, 1884 OCLC 559318239.

- Garratt, G.R.M., "The early history of telegraphy", Philips Technical Review, vol. 26, no. 8/9, pp. 268–284, 21 April 1966.

- Hamel, Joseph von, Historical Account of the Introduction of the Galvanic and Electro-magnetic Telegraph, London: W. Trounce, 1859 OCLC 25124947.

- Hubbard, Geoffrey, Cooke and Wheatstone: And the Invention of the Electric Telegraph, Routledge, 2013 ISBN 1135028508.

- Huurdeman, A.A., The Worldwide History of Telecommunications, Wiley, 2003 ISBN 0471205052

- Shaffner, Taliaferro Preston, The Telegraph Manual, Pudney & Russell, 1859 OCLC 258508686.

- Siegert, Bernard, Relays: Literature as an Epoch of the Postal System, Stanford University Press, 1999 ISBN 0804732388.

- Vail, Alfred, The American Electro Magnetic Telegraph, Lea & Blanchard, 1845 OCLC 933149657.

- Yarotsky, A.V., "150th anniversary of the electromagnetic telegraph", Telecommunication Journal, vol. 49, no. 10, pp. 709–715, October 1982.