Partnair Flight 394

Partnair Flight 394 was a chartered flight which crashed on 8 September 1989 off the coast of Denmark, 18 km (11 mi) north of Hirtshals. All 50 passengers and 5 crew members on board the aircraft died, and it is the deadliest aviation disaster in Denmark. The crash was caused by use of counterfeit aircraft parts in repairs and maintenance.

LN-PAA, the CV-580 involved, photographed in September 1987 | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 8 September 1989 |

| Summary | Rudder malfunction due to improper maintenance; loss of control |

| Site | 18 km north of Hirtshals, Denmark |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Convair CV-580 |

| Operator | Partnair |

| Registration | LN-PAA |

| Flight origin | Oslo Airport, Fornebu, Oslo, Norway |

| Destination | Hamburg Airport, Hamburg, West Germany |

| Occupants | 55 |

| Passengers | 50 |

| Crew | 5 |

| Fatalities | 55 |

| Survivors | 0 |

Aircraft

The aircraft, registered LN-PAA, was a 36-year-old Convair CV-580 operated by the charter airline Partnair. The plane had switched owners several times and had various modifications.[1][2] The aircraft had multiple previous registrations, N73128, EC-FDP, PK-GDS, HR-SAX, JA101C, N770PR and C-GKFT and had been rebuilt after a landing accident in 1978.[3][4] The most significant modification was a change from piston engines to turboprop engines in 1960; this added more horsepower to the aircraft.[2] A Canadian company that specialized in servicing Convairs was the owner of the aircraft before Partnair acquired it. LN-PAA was one of the most recently acquired aircraft in the Partnair fleet.[1] At the time of the crash, there were 2 other Convair 580 in the Partnair fleet.

Background

At the time of the accident Partnair was in financial difficulty. The airline's debts were such that, on the day of the accident flight, Norwegian aviation authorities had notified Norwegian airports to not allow Partnair aircraft to depart since Partnair had not paid several charges and fees.[1]

Flight

The Convair 580 aircraft was en route from Oslo Airport, Fornebu, Norway to Hamburg Airport, West Germany. The passengers were employees of the shipping company Wilhelmsen Lines who were flying to Hamburg for the launching ceremony of a new ship. Half of the employees of the company's head office were on board. Leif Terje Løddesøl, an executive of Wilhelmsen, said that the atmosphere in the company was "very very good" prior to the accident flight. He said that some of the employees "maybe" had been to prior naming ceremonies, which he described as "quite exciting." A regular employee on the flight, one of the top-performing employees in the company, had been asked to give the speech during the launching ceremony. Løddesøl said that it was not often that a "normal person" in the company was chosen to read the speech at the naming ceremony.[1]

The flight crew consisted of Captain Knut Tveiten and First Officer Finn Petter Berg, both 59. Tveiten and Berg were close friends who had flown together for years. Both pilots were very experienced, with close to 17,000 successful flight hours each. Berg was also the company's Flight Operations Manager.

Before the flight, the crew found that one of the two main power generators was defective and had been so since 6 September. Also the mechanic who had inspected the aircraft was unable to repair it. In the Norwegian jurisdiction an aircraft is only allowed to take off if it has two operable sources of power.[1][2] Also the aircraft's Minimum Equipment List required two operating generators.[2] The first officer decided that he would run the auxiliary power unit (APU) throughout the flight so that the flight would have two sources of power and therefore be allowed to leave.

The airport refused to let the flight go until the catering bill was paid. Before the aircraft took off, the first officer left the cockpit to pay the catering company. As a result of this, the plane was delayed by almost an hour, finally departing at 3:59 p.m.[1][2]

As the Partnair aircraft passed over the water at its planned cruising attitude of 22 000 feet,[2] a Norwegian F-16 Fighting Falcon fighter jet passed by it. The fighter pilot was startled by the sudden appearance of the aircraft and contacted Oslo air traffic control. He believed that the radar data to be false and that the aircraft was closer to his jet than his on-board computer had indicated.[5]

As the aircraft neared the Danish coastline, 22,000 feet (6,706 m) over the North Sea, Copenhagen Air Traffic Control saw that Flight 394 was off course and falling quickly, appearing to crash into the sea, roughly 20 km north of the Danish coast.[1]

Investigation

Accident Investigation Board Norway (AIBN) investigated the disaster and were able to recover 50 of the 55 bodies before sending them through autopsies in Denmark. Investigators used side-scan sonar to plot positions of wreckage. The pieces had settled over an area 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) wide, leading the investigators to believe that the aircraft disintegrated in the air. Luckily, 90% of the aircraft could be reconstructed.[1][2]

In an accident flight, the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) can usually record its final minutes. In the Partnair crash, however, it had recorded the start of the flight and stopped shortly before the aircraft took off. From the maintenance records investigators found that, 10 years prior to the accident flight, the cockpit voice recorder's power supply had been re-wired to connect to the aircraft's generator instead of the aircraft's battery if full power was applied for takeoff.[2] As the generator was inoperative on this flight, power to the CVR shut off as the aircraft took off.

Some initial speculation stated that explosives brought down Flight 394. Indeed, in December 1988, a bomb had brought down Pan Am Flight 103. In addition, Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland had used that particular Partnair aircraft on her campaign trips. The Norwegian press believed that the crash was an assassination attempt. Witnesses of the crash said that they heard a loud noise as they saw the aircraft fall. The fact that the aircraft had disintegrated in the air gave credibility to the bomb theory.[1] The speculation in the press later included a scenario where the plane had been shot down, possibly by the NATO war exercise "Operation Sharp Spear," which took place on the day of the accident flight near the flight path, as investigators had found small traces of high explosives on parts recovered from the sea bed. However, investigators found that the residue was not from a bomb or a warhead, as there was not enough of it present. Finn Heimdal, an AIBN investigator, said in an interview that the residue appeared to be more like a contamination than any other possibility. The sea had old munitions as many battles had been fought off the coast of Denmark. Investigators concluded that the aircraft pieces acquired residue from the bottom of the sea or that the traces of explosives were accumulated from contamination before the accident or due to storage.[1][2]

Metallurgist Terry Heaslip of the Canadian company Accident Investigation and Research Inc. examined the aircraft skin from the tail and found signs of overheating, specifically that the skin had been repeatedly flexed, through a phenomenon known as flutter. This caused investigators to further scrutinize the tail of the aircraft. Furthermore, the investigation team found that the Auxiliary Power Unit (APU), which was in the tail, generated heat which melted certain plastic parts, indicating that the APU was operating during the flight even though it normally would not be. The mechanic who had inspected the aircraft on the day of the accident flight told the investigators that one of the aircraft's two main generators had failed and that he was not able to repair the faulty generator. The investigators discovered that the pilots had noted in the flight log that they would operate the APU throughout the flight, since two power sources are required for flight.[2] They also discovered that the front APU mount was broken, which allowed it to vibrate excessively.

The two shroud doors on the aircraft tail were not present in the recovery. They were constructed with an aluminium honeycomb liner, and aluminium's reflective properties allowed the doors to appear on radar when floating free. This led the AIBN to conclude that the unidentified objects tracked at a high altitude by Swedish radar for 38 minutes were likely the shroud doors, which had separated from the aircraft tail. From this, the AIBN found that the tail failed at 22,000 feet. If the rudder moved in a violent manner, the weights behind the doors would also move violently and hit the shroud doors. Therefore, the rudder had made a violent movement as the accident unfolded.[1][2]

Partnair suggested said that the F-16 fighter jet had been flying at a faster velocity and closer to the Convair than reported in the media. Therefore, the jet, which would have broken the supersonic barrier at that point, would have created a supersonic pressure wave that would have caused the Convair to disintegrate in mid-air.[1] The National Aeronautical Research Institute, a Swedish aviation technology research facility, said that there was a 60% chance of this being the cause.[6] The Norwegian F-16 pilot testified that his aircraft was more than 1,000 ft (300 m) above the Convair. The investigators concluded that the F-16 would have had to have been within a few metres of the Convair to have affected the passenger aircraft in such a manner and had found no evidence that the two aircraft were that close together, and the AIBN investigation found no connection to the accident.[1][2] After the final report was issued, there was speculation that the AIBN had doubted the radar information that it received, leading the Thoresen brothers to file a lawsuit, but a ruling in the Norwegian lagmannsrett (intermediate court) dismissed this in 2004.[5][6]

The flight data recorder (FDR) was an antiquated analog model which used metal foil strips scratched by moving pins. Here, it did not record vertical acceleration readings and misrecorded heading indications.[2] One needle recorded some lines twice, initially confusing the investigators, leading the team to send the FDR to the American company which manufactured it.[1] The manufacturer asked an ex-employee, the highest expert regarding the company's flight data recorders, to temporarily leave retirement to examine the recorder. The expert concluded that the needle supposed to have been recording the altitude had been shaking so much that it left other stray marks on the foil. This particular FDR was able to record for hundreds of hours; further investigations found that the needle had been shaking abnormally for months. This told investigators that another component, not just the APU with the broken mount, had also been vibrating. The investigators charted the vibrations and found that two months before the crash, the vibrations stopped for two weeks, from immediately after the aircraft received a major overhaul in Canada by the airline's previous owner. During the Canadian company's test flights of the aircraft and its first several passenger flights for Partnair, the FDR recorded almost no abnormal vibrations. A review of the maintenance records of the aircraft revealed that during the overhaul, the mechanic discovered wear on one of the four bolts that held the vertical fin and fuselage together and replaced it. The vibrations stopped after the one bolt, and its associated sleeves, was replaced. When the vibrations later returned, they steadily increased up to the accident flight.

After investigators recovered all four bolts, sleeves, and pins, they found that bolt and parts installed by the Canadian firm were properly approved equipment, but the other three bolts and their parts were counterfeit and were incorrectly heat-treated during manufacture. Those bolts each could bear only about 60% of their intended breaking strength, making them less than practical to use on the aircraft. The fake bolts and sleeves wore down excessively, causing the tail to vibrate for 16 completed flights and the accident flight.[2]

The investigators concluded that eventually, the broken mount of the APU and the weak bolts holding the tail meant that both pieces were vibrating, and these vibrations reached the same frequency and went into resonance, where the force of multiple same-frequency vibrations add to that of one another and create one large vibration. Thus, the tail's vibration increased in amplitude until it failed and broke off.[1][2]

Dramatization

The crash was featured in Season 7 of the internationally distributed Canadian made documentary series, Mayday, in the episode entitled "Blown Apart".

Maps

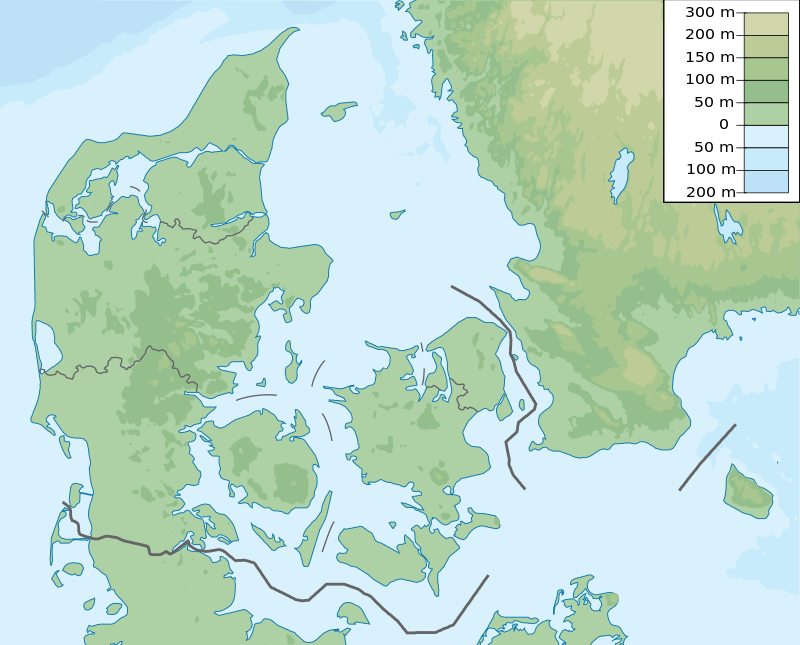

Oslo Hamburg Crash site Location of the accident and the airports |

Crash site Crash site in Denmark |

References

- "Blown Apart." Mayday. [TV documentary series]

- AIB-Norway's report on the accident (Norwegian original version) Archived 27 June 2011 at WebCite (Archive) – (English translation) (Archive)

- Flight International (1989) p16

- Letter in the Norwegian parliament to the Minister of Communications (in Norwegian)

- "New information on 1989 Norwegian crash revealed". Airline Industry Information. 21 March 2001. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- "Retten tror ikke på Partnair-teori" (in Norwegian). NTB, Nettavisen. 5 February 2004. Archived from the original on 6 February 2004. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- "Norway crash Convair had been rebuilt", Flight International, p. 16, 23 September 1989

- "Maintenance a factor in crash", Flight International, p. 13, 31 March – 6 April 1993

External links

- AIB-Norway's report on the accident (English version) (Archive)

- AIB-Norway's report on the accident (in Norwegian) (Archive)

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- Article by Snorre Sklet on major Norwegian disasters (see page 139, PDF file, article is in Norwegian)