Paramilitary punishment attacks in Northern Ireland

Since the early 1970s, extrajudicial punishment attacks have been carried out by Ulster loyalist and Irish republican paramilitary groups in Northern Ireland. Attacks can range from a warning or expulsion from Northern Ireland, backed up by the threat of violence, to severe beatings that leave victims in hospital and shootings in the limbs (such as kneecapping). The cause of the attacks is disputed; proposed explanations include the breakdown of order as a result of the Northern Ireland conflict (c. 1970–1998), ideological opposition to British law enforcement (in the case of republicans), and the ineffectiveness of police to prevent crime.

Since reporting began in 1973, more than 6,106 shootings and beatings have been reported to the police, leading to at least 115 deaths. The official figures are an underestimate because many attacks are not reported. Most victims are young men and boys under the age of thirty years, whom their attackers claim are responsible for criminal or antisocial behaviour. Despite attempts to put an end to the practice, according to researcher Sharon Mallon in a 2017 policy briefing, "paramilitaries are continuing to operate an informal criminal justice system, with a degree of political and legal impunity".[1]

Name

The term "punishment" is controversial. According to Liam Kennedy, "Not only has the label 'punishment' a euphemistic quality when applied to extremely cruel practices, it also carries a presumption that the victim is somehow deserving of what he (occasionally she) receives."[2] In a 2001 debate in the Northern Ireland Assembly, Alliance MLA Eileen Bell stated, "I am appalled at the DUP’s use of the term 'punishment beatings'. The use of the term 'punishment' confers on the act a degree of legitimacy by suggesting that the guilt of a victim is an established fact."[3] According to the Independent Monitoring Commission, the term "punishment beating" "lends a spurious respectability to the perpetrators, as if they were entitled to take the law into their own hands".[4] Families Against Intimidation and Terror refers to the attacks as "mutilation" rather than "punishment".[5] "Paramilitary policing" is an alternative term used by some sources.[6][7] "Internal housekeeping" is a euphemism, coined by Northern Ireland secretary Mo Mowlam in 1999.[8]

Background

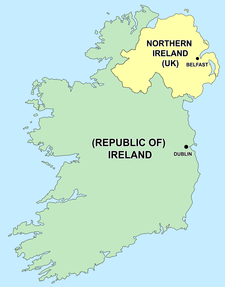

From the late 1960s to 1998, the Northern Ireland conflict (also known as the Troubles), was a civil war between Irish republican groups, who wanted Northern Ireland to leave the United Kingdom and unite with the Republic of Ireland, and Ulster loyalist groups, who wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of the UK.[9][10] The origin of the conflict occurred during the Irish revolutionary period of the early twentieth century, during which most of Ireland seceded from the UK and became the Irish Free State, while the northern six counties opted to remain under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty.[11] The Irish republican movement considers itself the legitimate successor of the Irish Republic of 1919 to 1921.[12] Irish republicans do not recognize the partition and consider ongoing British rule in Ireland to be a foreign occupation.[13][14]

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) was the largest republican paramilitaries group, while smaller groups include the Irish National Liberation Army[15] and the Official IRA.[16] All three ceased military activity during the Northern Ireland peace process, which led to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, the official end of the conflict. However, dissident republicans—such as the Real IRA and the Continuity IRA—do not recognize the peace agreement and wage an ongoing campaign.[17] The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) are rival groups[18] that are responsible for the majority of loyalist murders during the Troubles, while smaller loyalist groups include the Red Hand Commando,[15] Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF), and Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF).[19] Both republican and loyalist groups consider punishment attacks separate from military activity[20] and continue to carry them out while on ceasefire status.[15][17]

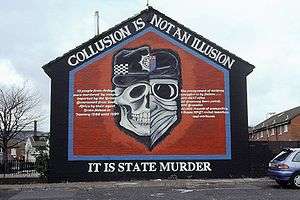

British troops were deployed in Northern Ireland from 1969 to 2007.[21][22] The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) was an armed force that took a military approach to counter-terrorism,[23] had been drawn into pro-unionist sectarianism,[24] colluded with loyalist groups,[25] and committed police brutality, including beatings of suspects.[24] Real and perceived human rights violations by security forces—including internment without trial, special courts for political offences, the use of plastic bullets by riot police, and alleged shoot-to-kill policy—further sapped the state's legitimacy for nationalists.[23][26][27] In many neighborhoods, the RUC was so focused on terrorism that it neglected ordinary policing, regular patrols, and non-political crime. Both nationalist and unionist communities complained that the RUC did not respond quickly enough to calls relating to petty crime, and that suspects were pressured to inform on paramilitaries.[28][7]

Since the replacement of the RUC with the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) in 2001,[29][30] trust has improved, with more than 70% in both communities having a positive assessment of the PSNI's performance.[31] However, in many republican neighbourhoods identity has been shaped by distrust of the authorities,[32] with one republican neighbourhood in West Belfast reporting only 35% trust in the police.[31] Since the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement[33] and the disbanding of the RUC, trust is decreasing in some loyalist communities.[31] Among the complaints are harassment by security forces,[34] the ineffectiveness of the police, and perceived leniency of sentences meted out by British courts.[35]

Origins

Irish nationalist movements have a long history of establishing alternative legal systems, especially the land courts of the Land War and the Dáil Courts during the Anglo-Irish War.[36][37][38] In Northern Ireland, the alternative justice system survived partition and continued into the first years of the Northern Ireland polity.[38] Following partition, loyalist militias patrolled parts of the border with the Irish Free State and, in Belfast, the Ulster Unionist Labour Association set up an unofficial police force in the 1920s.[39]

In the late 1960s, armed loyalists attacked Catholic communities in response to the Northern Ireland civil rights movement.[39] To protect themselves, nationalists set up Citizen Defence Committees (not connected to physical-force republican groups) which built and manned barricades and patrolled the neighborhood. In nationalist neighborhoods of Derry such as the Bogside, Brandywell, and Creggan, these committees worked to control petty crime by delivering stern lectures to offenders. In the 1970s, the Free Derry Police also operated independent of paramilitary groups. "People's courts" which mostly imposed sentences of community service based on a restorative justice approach operated in the early years of the conflict, but shut down due to police intimidation and because they did not have the authority of punishment imposed by paramilitaries.[39][40][41] In nationalist Belfast, the Catholic Ex-Servicemen's Association initially played a role in keeping order.[42] At the same time, Protestant neighbourhoods began to organize defence groups in response to retaliatory raids. Such groups formed the basis of the UDA.[39][43]

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) became the major enforcer of informal justice in republican areas in the early 1970s, as the civil rights movement transitioned into guerilla war.[40] The RUC stopped entering West Belfast—an economically deprived, overcrowded republican area—in 1969, creating a "no-go area",[39][44] and many rural areas had a system of dual control between the IRA and the authorities.[45] At the same time, there was a spike in crime: from two murders and three or four armed robberies each year in the 1960s to 200 murders and 600 armed robberies annually during the next decade.[46] Despite making the news, rates of car theft were actually still lower in Northern Ireland than in England and Wales, although 70% of car thefts in Northern Ireland occurred in Belfast.[47] Petty criminals were often offered immunity by law enforcement in exchange for informing on paramilitaries.[48] The origins of paramilitary vigilantism are not well documented,[49] but sociologist Ronaldo Munck considers them to originate from "community consciousness".[50] During the first ten years of the Northern Ireland conflict, police did not enter republican areas.[46] During the 1975 truce, "Provo Police Stations" were set up by Sinn Féin,[51] the political wing of the IRA.[52] These centers shifted the responsibility of informal justice from the IRA to Sinn Féin. Once a crime had been reported to Sinn Féin, the party would assign its Civil Administration Officers to investigate. Suspects often were given the opportunity to defend themselves to Sinn Féin before the organization made a decision on their guilt or innocence. Sinn Féin could issue a warning or pass the information to the IRA for punishment.[53]

Causes

One cause of vigilantism is the breakdown in law and order and lack of trust in the authorities.[54][55] According to anthropologist Neil Jarman, vigilantism emerged in both loyalist and republican areas due to the failings in state policing, a gap which paramilitaries ended up filling.[55] According to Munck, punishment attacks represent "a sharp contest over the legitimacy of criminal justice within a society deeply divided along ethno-national lines".[13] In republican neighbourhoods, the IRA was the only organization with the capability to offer an effective alternative to the British judicial system.[14] The ideology of self-reliance in defence from loyalist attacks came to extend to defending the community from crime, which created a cycle where the IRA was expected to deal with criminality but had no way to do so besides violent attacks.[56][57][lower-alpha 1]

Andersonstown News, 18 March 2000[59]

Dissident republican spokesperson in a 2018 BBC Three documentary[60]

Popular demand for paramilitary punishment is widely regarded as one of the main causes of the attacks.[61] Both republican and loyalist paramilitaries claim that they began to enforce informal justice due to demand from their communities,[54] and vigilantism came at the expense of the IRA's military campaign.[62] Many locals believe the victims deserve the attacks, because they have typically broken local conventions governing acceptable behaviour and often actively seek out the circumstances that led to their punishment.[63][64][57] Some local republican and loyalist politicians have justified the attacks by saying that the official system fails working-class communities[57] which bear the brunt of crime.[65] In community meetings attended by criminologist Kieran McEvoy and sociologist Harry Mika around the turn of the century, the authors frequently encountered "vocal support for punishment violence" and accusations that local politicians who supported restorative justice were "abandoning" their responsibility to protect their communities.[20]

Unlike law enforcement, which is bound by due process, paramilitaries can act swiftly and directly in punishing offenders.[66][67] (Conviction rates for crimes such as burglary and joyriding are very low, due to the difficulty of securing evidence.[68]) Because of the tight-knit nature of Northern Ireland communities, paramilitaries can often find the perpetrator via local gossip.[69] Local residents credit paramilitaries for keeping Belfast relatively free of drugs[70] and non-political crime.[71] In 2019, Foreign Policy reported that PSNI still "finds itself powerless in the face of influential paramilitaries" to stop punishment attacks. In the words of a local resident, many people feel that "at least somebody’s doing something about [drug dealing]".[72] According to surveys, the number of Northern Ireland residents living in affected areas who think that punishment attacks are sometimes justified has decreased from 35% to 19% following the Department of Justice's 2018 "Ending the Harm" campaign.[73]

After the ceasefires declared by loyalist and republican paramilitaries in 1994, the number of shootings decreased while beatings increased as the groups wanted to appear to be following the terms of the ceasefire.[74] (In the months before the ceasefire, there had been a wave of shootings.[75]) The overall rate of attacks spiked; one explanation for the rise in attacks was the decrease in conventional terrorism, which resulted in bored paramilitaries who turned their attention to punishment attacks.[5] However, according to researcher Dermot Feenan there is no evidence for this.[76] After the peace agreement was finalized in 1998, the number of fatal terrorist attacks greatly decreased but beatings and intimidation continued to increase.[77] Within a few years shooting attacks were also on the rise.[74]

According to some writers, including Liam Kennedy and Malachi O'Doherty,[20] protecting their own communities is only a pretext and the paramilitaries' real goal is to consolidate control over the community.[78][79][76] Kennedy argues that paramilitaries are attempting to consolidate "a patchwork of Mafia-style mini-states" via vigilante violence and economically sustained by extortion and racketeering.[80] Some have argued that paramilitary vigilantes only target drug dealers because they compete with paramilitary-sponsored organized crime.[14] However, researchers argue that "the notion that paramilitaries can 'control' local communities is something of a myth"[81] which ignores the dependence of paramilitaries on their communities and the support for paramilitarism within those communities.[81][34][82] Terrorism researcher Andrew Silke argues that both loyalist and republican paramilitaries are reluctant vigilantes, and that their vigilantism is unrelated to their raison d'être. However, both informing and petty crime undermine the terrorist group, the latter because if the paramilitaries' response is not satisfactory, it can erode their local support.[83]

Perpetrators

Republican groups

The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) targeted both "political" and "normal" criminals. The IRA defined "political" crime as informing or fraternizing with British soldiers, while "normal" crime was judged to include vandalism, theft, joyriding, rape, selling drugs, and "antisocial behavior"—anything from verbally abusing the elderly to dumping rubbish. "Normal" crimes by first-time offenders were often dealt with by a restorative justice approach based on providing restitution to victims. The typical punishment for repeat offenders was kneecapping, a malicious wounding of the knee with a bullet.[40] The IRA claimed that its methods were more lenient than those of other insurgent groups, such as the Algerian FLN or the French resistance, which Munck agrees with.[85]

The IRA also punished its own members for misusing the organization's name, losing weapons, disobeying orders, or breaking other rules, and launched purges against other republican paramilitary groups such as the Irish People's Liberation Organisation and the Official IRA. Within the IRA, those responsible for punishment belonged to auxiliary cells and were considered the "dregs" of the organization. The IRA maintained distinct sections for internal and external punishment.[86] Although informers were usually executed, part of the IRA's strategy for defeating informers included periodic amnesties (usually announced after murders) during which anyone could admit to informing without punishment.[87] Around 1980, the system of punishment attacks was questioned by IRA figures, which resulted in the increase in warnings given. The IRA pledged to stop kneecapping in 1983, and both shootings and beatings drastically declined. However, soon community members were calling for more paramilitary attacks to combat an increase in crime, especially violent rapes.[88][89]

Other republican paramilitary groups also punished offenders but on a smaller scale.[86] Direct Action Against Drugs was an IRA front group that claimed responsibility for some murders of alleged drug dealers beginning in 1995, allowing the IRA to pretend to follow the ceasefire.[90] DAAD drew up a list of alleged drug dealers and crossed their names off the list as they were executed.[91] Other republican anti-drug vigilante groups include Republican Action Against Drugs,[92][93] Irish Republican Movement,[94] and Action Against Drugs.[60] Along with conventional terrorism, punishment attacks are a major feature of the dissident Irish republican campaign carried out by the New IRA and other groups.[78] However, the attacks are controversial among dissident republicans, who question whether any benefit of the attacks is worth the internal division and alienation of youth.[95]

Loyalist groups

Ulster loyalist paramilitaries, whilst not drawing on historical precedents, justified their role in terms of maintaining order and enforcing the law. Unlike republican vigilantes, however, they saw their role as aiding the Royal Ulster Constabulary rather than subverting it. Nevertheless, they were prepared to mete out their own punishments in cases where they judged the official justice system not to deal harshly enough with the alleged offender. In 1971, the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), the largest Ulster loyalist group, formed as a merger between various neighbourhood watch and vigilante groups. It adopted the motto Codenta Arma Togae ("law before violence") and states that its aim is to see order restored throughout Northern Ireland. The UDA has collected evidence on petty crime and used vigilante punishment against criminals, antisocial elements, rival Ulster loyalist paramilitary groups, and as a means of discipline within groups. It also used the threat of punishment in order to conscript new members. The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) used to patrol the Shankill neighbourhood in Belfast. Criminals were warned or reported to the official police.[96]

Between 1973 and 1985, loyalists were responsible for many fewer punishment attacks than republicans, due to a view that their role was protecting Protestants from Catholics rather than enforcing rules within Protestant communities. From 1985 to 1998, they were responsible for a similar number of attacks. According to insider Sammy Duddy, the UDA stopped reporting offenders to the police and started to engage in punishment shootings because the police was pressuring the offenders to inform on loyalist groups.[97] Since the Good Friday Agreement, loyalists have committed significantly more punishment attacks than republicans.[25] The increase in punishment attacks has been attributed to increasing mistrust of official law enforcement, ineffectiveness at controlling petty crime, and perceived leniency of sentences.[35] Both the UDA and UVF have less internal discipline than the IRA,[98][25] which means that an order to stop would be difficult to enforce. Loyalist groups' punishment style is more haphazard and groups who cannot find their intended target have been known to attack an innocent Catholic individual.[25] Individuals have joined loyalist paramilitaries to avoid a punishment attack from a rival group.[99]

In 1996, newspapers reported that the UVF had set up a "court" in Shankill which fined offenders for various offenses, but according to sociologist Heather Hamill this is more likely a reflection of ability to pay rather than a genuine justice system based on severity of the offence. In 2003, the North Belfast branch of the UDA announced that it was ceasing violent punishments in favour of "naming and shaming" offenders, who were forced to stand with placards announcing their offence. This change proved short lived.[100]

Attacks

Overview

The punishment methods of republican and loyalist paramilitaries are similar.[99] Because paramilitaries rely on popular support, they cannot overstep community consensus on appropriate punishment without risking the loss of support.[85] The penalty chosen would be based on the crime and potentially mitigating or aggravating factors such as criminal history, age, gender, and family background.[101] Crime against targets valued by the community, such as religious leaders, pensioners, community centers, or locally owned businesses, tended to be punished more harshly than crimes against large corporations, which were frequently ignored.[102] Punishment attacks often begin when masked paramilitaries break into the victim's home.[103] In other cases, victims would be told to show up at a certain time and place, either at a political front organization or at their home, for the attack.[104][105] Many victims keep these appointments because if they fail to do so, the punishment will be escalated in severity.[105] These appointments are more likely to be made by republican than loyalist groups.[99] Some victims were able to negotiate the type of punishment.[106] In order to avoid the victims dying, paramilitaries frequently call emergency services after the attack.[107] In cases of mistaken identity, the IRA was known to issue apologies after the fact.[104]

Initially, both republican and loyalist paramilitaries were reluctant to shoot or seriously harm women and children younger than 16, although this became more frequent as the Troubles continued.[101] Even female informers were usually subject to humiliation-type punishment rather than physical violence.[108][109] There were exceptions, such as the case of accused informer Jean McConville, who was kidnapped and killed in 1972.[109]

Non-physical

More minor punishments, often used on first offenders, are warnings, promises not to offend again, curfews, and fines.[109][103] Parents sometimes request that their child be warned in order to keep him or her from greater involvement in delinquency.[110] During the 1970s, when the IRA had the most control over established "no-go zones", humiliation was often used as a form of punishment. The victim was forced to hold a placard or tarred and feathered. In republican areas, women accused of fraternizing with British soldiers had their heads shaved. The use of such types of humiliation was greatest in the 1970s and decreased due to the risk of getting caught and complaints from Derry Women's Aid that the practice was misogynistic.[109][111]

Sometimes paramilitaries would approach a person and ask them to leave West Belfast[112] or Northern Ireland within a certain period of time (such as 48 hours), with an implicit threat of serious injury or execution if they did not comply.[104][58] It could be applied arbitrarily when paramilitaries go out looking for the victim but cannot find him, they will issue an expulsion order to friends or relatives.[105] Expulsion was an alternative to violence favoured by paramilitaries because it removed the offender from the community whilst avoiding bloodshed.[104] However, victims frequently experienced it as the worst form of attack short of execution. Most victims are young, unemployed and lack educational qualifications as well as the skills and savings needed to establish themselves in a new area.[113] Expulsion can be a life sentence but usually it lasts between three months and two years. Some victims, although they have not been convicted of any crime, go to juvenile detention centres to avoid punishment until their sentence expires.[105]

Beatings

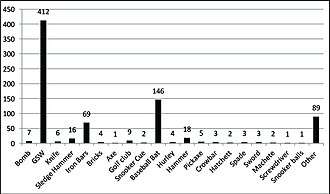

Some individuals report that the attack was quite mild and no more than a "cuff around the ear" or being slapped around. Other beatings are more severe and the victim ends up in hospital for considerable period of time. Beatings are accomplished with instruments such as baseball bats, hammers, golf clubs, hurley sticks, iron bars, concrete blocks, and cudgels (often studded with nails). The resulting injury can be quite severe, involving flesh split by nails, broken skulls, broken limbs, punctured lungs, and other serious damage.[114][104][115] More injuries affected the limbs than the torso. In some cases, paramilitaries used powered drills and hacksaws to directly injure bone.[116] Beatings became more severe after the 1994 ceasefires due to the reduction in shootings, and were often accomplished with baseball bats and similar implements studded with six-inch nails.[115] In the worst cases, individuals were hung from railings and nailed to fences in a form of crucifixion.[57]

Shootings

Victims are typically shot in the knees, ankles, thighs, elbows, ankles, or a combination of the above.[117] Kneecapping is considered a "trademark" of the IRA,[118] although it became less popular over time because the disability and mortality incurred was unpopular with the community. It was replaced with low-velocity shots aimed at the soft tissue in the lower limbs. As a result, "kneecapping" is frequently a misnomer because by the 2010s most injuries targeted the femur or popliteal area rather than the knee joint.[119][107][120] Typically, the victim is forced to lie face down and shot from behind.[118] Republican paramilitaries tended to shoot side to side while loyalists shot back to front, causing more severe damage.[107] As with beatings, there are various degrees of shooting, with the number of shots, proximity to a joint, and the calibre of the firearm depending on the severity of the offence. If the victim is shot in the fleshy part of the thigh, it will heal quickly with little damage. On the other hand, if they are shot directly in the joint it can cause permanent disability.[104][121] An especially severe form is the "six pack", during which a victim is shot in both knees, elbows, and ankles.[119] Depending on the attack, shooting can leave relatively minor injuries compared to a severe beating,[122][123] with one NHS doctor estimating that 50% of those with such injuries will have only minor scars.[124] The IRA sought the advice of doctors in how to cause serious but non-lethal injury. They were advised to shoot the ankles and wrists instead of the knees because it lessened the risk of the victim bleeding out, as happened to Andrew Kearney in 1998.[125] The harshest punishments are for informing, which typically results in execution.[126][127]

Consequences

According to psychiatrist Oscar Daly, who treats victims of the attacks, the characteristics of those who tend to be victims—such as poor parenting and preexisting mental health problems—make them more vulnerable to psychological sequelae. A 1995 study found that symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, such as flashbacks, hypervigilance, difficulty concentrating, and attempts to numb or minimize the incident, are common in youth who survive a punishment attack. According Hamill's research, desire to escape fear and the feeling of powerlessness can contribute to problems with alcoholism and drug abuse.[128] More than one third of her subjects suffered from extended bouts of depression following attacks and 22% said that they had attempted suicide.[129][66] Mallon analyzed the 402 suicides in Northern Ireland between 2007 and 2009 and identified nineteen cases in which young men had killed themselves after being threatened with punishment attacks for alleged criminal or anti-social behaviour.[130]

In 2002, the National Health Service estimated that it spent at least £1.5m annually on treating the victims of punishment attacks.[131] Depending on the time period under consideration, the per-patient cost of treating victims who have been physically attacked varies from £2,855 (2012–2013) to £6,017 (pre-1994) in 2015 pounds. These figures only include the first hospital admission and therefore do not include the cost of treating resulting psychological disorders. The lower cost is due both to less severe attacks and improved treatment techniques.[132] Many victims were treated at Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast, which developed expertise in dealing with the particular injuries involved.[133][116] Punishment beatings often leave victims with serious injuries and permanently disabled.[104] Kneecapping often resulted in neurovascular damage which had to be treated with weeks in the hospital and extensive outpatient rehabilitation.[116] However, medical advancements allowed most victims to regain most function in their limbs.[134] Between 1969 and 2003, 13 patients treated at Musgrave Park Hospital in Belfast required leg amputation because of kneecapping attacks.[135]

If considered "innocent victims of violent crime", victims of punishment attacks (like others injured by paramilitaries) are eligible for compensation by the Compensation Agency of the Northern Ireland Office.[136]

Statistics

Police received reports of 6,106 punishment attacks between 1973 and 2015, of which 3,113 incidents were attributed to loyalists and 2,993 to republicans.[137] At least 115 people were killed by these attacks between 1973 and 2000.[138] There have been additional deaths since then, such as multiple murders claimed by Republican Action Against Drugs and the killing of Michael McGibbon in 2016.[139][60] These statistics only include incidents reported to the police, and are therefore an underestimate.[35] Pressure group Families Against Intimidation and Terror claims that it is a 30–50% underestimate,[140] while according to Sharon Mallon, underreporting makes accurate measurement of these attacks impossible.[141] No statistics exist for other forms of penalties, such as expulsion,[lower-alpha 2] humiliation, fines, curfews, or warnings.[142] The estimates of incidents in the 1970s is particularly suspect, since punishment beatings were not counted.[5] Almost half of all reported attacks have occurred since the Good Friday agreement.[143]

Most victims of punishment attacks are young men or boys under 30 years of age.[100] Less than ten percent of victims are female.[144] About one-quarter of victims are under the age of 20 and the youngest are thirteen years old.[84] Victims of loyalists are older on average; 33% are over the age of 30 years compared to 15% for republicans.[145] Since 1990, half of victims were attacked in Belfast.[137] In most attacks, only one person is assaulted. Resistance is rarely attempted, because most victims perceive their situation to be hopeless. Sometimes, if a bystander steps in to defend the targeted person, they will be attacked as well.[146] About three-quarters of attacks take place between 16:00 and midnight; the majority begin in the victim's residence (often they are abducted and taken elsewhere for the main attack).[147] Most loyalist attacks involve between three and five attackers, but two-thirds of IRA attacks involve five or more attackers.[148]

After a decrease in the early 2000s, punishment attacks are increasing again.[66][149] In 2018, Community Restorative Justice Ireland estimated that each year there are 250-300 threats, significantly higher than the number reported to PSNI.[60] Between July 2018 and June 2019, 81 punishment attacks were reported to the police, on average more than one every four days.[73] From January to November 2019, 68 attacks were reported.[150]

Victims

"Hoods"

Most victims come from a delinquent youth subculture colloquially known as "hoods".[151][152][45] Offences that they commit range from organized drug dealing to joyriding.[45] Hoods continue to offend even though they know that this puts them at high risk of punishment. According to research by Heather Hamill, this is because prestige in this subculture is based on costly signals of toughness and individuals are able to attain even higher prestige when they show that they are undeterred by punishment attacks.[153] According to Munck, hoods regard having been kneecapped as a "mark of prestige".[45]

Drug dealing is particularly strongly opposed by the IRA, with the commander of the Belfast Brigade declaring that drugs are the "poison of our community" and their purveyors responsible for "CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY".[154]

Politically motivated attacks

Other victims are attacked for political reasons, such as part of feuds with other groups. For example, in 1998 the IRA attacked both Kevin McQuillan, a leader in the rival Irish Republican Socialist Party, and Michael Donnelly, chairman of Republican Sinn Féin in Derry.[155] One reason for the resurgence of dissident republicans after the IRA's disbanding in 2005 was that previously, the organization had been conducting campaigns of social ostracism, intimidation, kidnapping, and assassination against dissident republicans.[156] These attacks deter opponents of paramilitary groups from criticizing them.[157]

Other victims, such as Andrew Kearney and Andrew Peden, were attacked after quarreling with paramilitary members.[158][159]

Sexual offences

Republican and loyalist paramilitaries both targeted gay men and individuals suspected of molesting children.[160] Loyalist paramilitaries also deal harshly with sexual crimes. One Presbyterian minister, David J. Templeton, was caught with homosexual pornography and died after a beating by the UVF in 1997.[99][161] Republican paramilitaries shot a 79-year-old man in both arms and legs after mistaking him for an accused child molester.[84]

Opposition

Campaigning

Punishment attacks are condemned by all major political parties in Northern Ireland[3][57] and by religious leaders.[162] In 1990, Nancy Gracey set up the organization Families Against Intimidation and Terror to oppose punishment attacks after her grandson was killed in one.[91] Historian Liam Kennedy has campaigned against the attacks, which he considers a form of child abuse, considering that many victims are minors and some younger than 14. Kennedy has accused Sinn Féin of involvement in the attacks, which the party denies.[163] Beginning in the 1970s, the RUC conducted a propaganda campaign against punishment attacks, seeking to portray their perpetrators as preying on an innocent, harmonious community and seeking a "monopoly on crime for themselves".[160] In 2018, the PSNI launched the "Ending the Harm" campaign to raise awareness of punishment attacks.[73]

Legality

Extrajudicial violence and threats are illegal in the United Kingdom.[164] People who carry out punishment attacks can be prosecuted for crimes such as assault, battery, and bodily harm.[19] The sixth of the Mitchell Principles, which paramilitary groups agreed to abide by in 1998, explicitly forbids extrajudicial punishment and requires that signatories put an end to the practice.[165] The United States was reluctant to threaten the success of the peace process due to punishment attacks, because it considered that these did not fit the conventional definition of terrorism.[166] As a result, the victims of punishment attacks became "expendable and legitimate targets for violence".[167] However, it was "intolerably awkward ... to turn a blind eye to vigilante murder".[168] The ban on punishment attacks was never well enforced, and paramilitaries make a distinction between "punishment" and military actions, only ceasing the latter. Loyalist paramilitaries UDA, UFF, and LVF were re-listed as terrorist organizations in October 2001 after they were found to be involved in punishment attacks.[74]

The authorities have been unable or unwilling to prosecute the perpetrators of the attacks, because attackers usually wear masks and even if aware of their identity, many victims are reluctant to identify them for fear of retaliation.[107][169] Of 317 punishment attacks reported to the PSNI between 2013 and 2017, only 10 cases resulted in charges or a court summons.[170] According to research by Andrew Silke and Max Taylor on punishment attacks between July 1994 and December 1996, loyalists were convicted at a four times higher rate than republican attackers for their participation in attacks. This was because working-class Protestants were more likely to cooperate with the police.[171] In a plurality of cases analyzed by Silke and Taylor, there are no witnesses besides the victim.[148] PSNI established the Paramilitary Crime Task Force in 2017, in part to crack down on punishment attacks.[60][172]

According to Human Rights Watch, Common Article 3 of the 1949 Geneva Convention, which lays down rules for internal armed conflicts, applies to the Northern Ireland conflict.[173] Punishment attacks constitute torture,[103] "violate the right to life, freedom from humiliating and degrading treatment, the right to due process and the guarantee of a fair trial".[173]

Restorative justice

In 1990, the Belfast-based victim support group Base 2 was founded. In the first eight years, it helped more than 1,000 people stay in their communities and avoid punishment attacks.[174] Since then, there have been community-based attempts to mediate conflict between paramilitaries and their targets via a restorative justice approach. These interventions have included verifying if an individual is under sentence of expulsion, helping such individuals relocate elsewhere, and eventually reintegrating them into the community.[175] Alleged offenders may be offered mediation with the wronged party and asked to offer restitution or perform community service. As part of the programme, they have to stop the behaviour and cease using alcohol and drugs. These are voluntary programmes, and require the agreement of both parties. Some offenders prefer the official justice system or to suffer paramilitary punishment.[176]

Sinn Féin supported restorative justice, which was endorsed by the IRA in 1999; the organization also asked locals to stop requesting punishment attacks.[177] About this time, Community Restorative Justice Ireland (CRJI) was established to coordinate restorative justice initiatives in republican areas.[178][179] The RUC's opposition to the centres made them ideologically acceptable to republicans.[177] Before 2007, the republican restorative justice centres did not cooperate with the PSNI.[180] CRJI is opposed by dissident republicans; Saoirse Irish Freedom (the organ of Republican Sinn Féin) once described it as "British double speak for collaboration with Crown Forces".[181] Loyalist neighbourhoods have also seen community restorative justice approaches, organized by Northern Ireland Alternatives,[143] which originated in the greater Shankill area[179] and worked closely with the police from the beginning,[180] despite scepticism from law enforcement.[179]

Proponents of restorative justice argue that they are the only way to end paramilitary violence and are a legitimate form of legal pluralism.[143][182] According to a study by Atlantic Philanthropies, Alternatives prevented 71% of punishment attacks by loyalists and CRJI prevented 81% of attacks by republicans.[183] Critics argue that the restorative justice approach legitimizes the role of paramilitaries in informal justice and allows them to retain the threat of violent attacks if they are not satisfied with the result.[143][182] In 2006, the eighth report of the International Monitoring Commission described participation in restorative justice as one means by which paramilitaries attempted to maintain their role and exert influence.[12] Another argument against restorative justice is that it institutionalizes a different justice system for the rich and poor.[184]

Notes

- Some paramilitary groups do have the ability to hold prisoners captive for extended periods of time. However, this strains their resources so much that it can only be used rarely.[58]

- Belfast victim-support group Base 2 knows of 453 people who were expelled between 1994 and 1996. Of these, 42% were expelled from Northern Ireland, 20% were ordered to leave their town, and 38% had to leave their neighbourhood only.[58]

References

Citations

- Mallon 2017, p. 8.

- Kennedy 1995, p. 86, cited in Human Rights Watch 1997, 5. Paramilitary "Policing", fn 224.

- "Punishment Beatings: 23 Jan 2001: Northern Ireland Assembly debates". TheyWorkForYou. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Gallaher 2011, p. 10.

- Silke & Taylor 2002, p. 14.

- Conway 1997, p. 109.

- Cavanaugh 1997, p. 48.

- Gallaher 2011, p. 9.

- Steinberg 2019, pp. 79, 82.

- Stevenson 1996, p. 126.

- Steinberg 2019, p. 81.

- Jarman 2007, p. 10.

- Munck 1984, p. 151.

- Brooks 2019, p. 211.

- Higgins, Erica Doyle (8 August 2016). "The UVF, UDA, PIRA and the INLA: Paramilitary groups of Northern Ireland explained". The Irish Post. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Knox & Monaghan 2002, p. 38.

- "Activities and structure of the paramilitaries". The Irish Times. Independent Monitoring Commission. 22 April 2004. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Knox & Monaghan 2002, p. 40.

- Knox & Monaghan 2002, p. 43.

- McEvoy & Mika 2002, p. 536.

- Murphy 2009, p. 34.

- Oliver, Mark (31 July 2007). "Operation Banner, 1969-2007". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Murphy 2009, p. 38.

- Murphy 2009, pp. 34–35.

- Hamill 2011, p. 136.

- Munck 1984, p. 85.

- Feenan 2002b, p. 155.

- Human Rights Watch 1997, 5. Paramilitary "Policing": Introduction.

- Murphy 2009, p. 45.

- Jarman 2007, p. 1.

- Bradford et al. 2018, p. 2.

- Bradford et al. 2018, p. 4.

- Cavanaugh 1997, pp. 48–49.

- Cavanaugh 1997, p. 49.

- Monaghan 2002, p. 51.

- Munck 1984, pp. 82–83.

- Monaghan 2002, p. 41–43.

- Feenan 2002b, p. 152.

- Feenan 2002b, p. 153.

- Monaghan 2002, pp. 44–45.

- Monaghan 2004, p. 439.

- Knox & Monaghan 2002, pp. 31–32.

- Feenan 2002a, p. 42.

- McCorry & Morrissey 1989, p. 283.

- Munck 1984, p. 91.

- Munck 1984, p. 89.

- McCorry & Morrissey 1989, pp. 286–287.

- Munck 1984, pp. 87, 91.

- Jarman 2007, p. 7.

- Munck 1984, pp. 85–86.

- Monaghan 2002, p. 45.

- Stevenson 1996, p. 125.

- Monaghan 2002, pp. 45–46.

- Monaghan 2002, pp. 44, 52.

- Jarman 2007, pp. 3, 7.

- McEvoy & Mika 2001, pp. 362–363.

- Jarman 2007, p. 9.

- Silke 1998, p. 131.

- Hamill 2002, p. 62.

- Stallard, Jenny (13 September 2018). "Stacey Dooley investigates: The men shot by their neighbours". BBC Three. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Feenan 2002b, p. 156.

- McEvoy & Mika 2001, p. 362.

- Hamill 2002, p. 68.

- Hamill 2011, pp. 66–67.

- Munck 1984, p. 92.

- Mallon et al. 2019, p. 2.

- McEvoy & Mika 2002, p. 362.

- Peyton 2002, p. s53.

- Brewer et al. 1998, pp. 580–581.

- McKittrick, David (21 December 1995). "How the guns kept drugs out of Belfast". The Independent. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Brewer et al. 1998, p. 581.

- Haverty, Dan (24 May 2019). "Paramilitaries Are Surging Again in Northern Ireland". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Moriarty, Gerry (5 August 2019). "Northern Ireland: Eighty-one 'punishment attacks' in past year". The Irish Times. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Knox & Monaghan 2002, pp. 42–43.

- Conway 1997, p. 116.

- Feenan 2002b, p. 164.

- Mallon et al. 2019, p. 1.

- Morrison 2016, p. 599.

- McEvoy & Mika 2001, p. 361.

- Kennedy 2001, Trends over Time.

- McEvoy & Mika 2002, p. 546.

- Feenan 2002b, pp. 155, 164.

- Silke 1998, pp. 133–134.

- Knox & Dickson 2002, p. 6.

- Munck 1984, p. 86.

- Monaghan 2002, pp. 46–47.

- Sarma 2013, p. 254.

- Munck 1984, pp. 89–90.

- Feenan 2002b, p. 157.

- Moran 2009, p. 32.

- Freer, Bridget (7 March 1996). "Saying no to Ulster's dirty war". The Independent. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Why a mother took her teenage son to be shot by vigilante terrorists Republican Action Against Drugs". Belfast Telegraph. 17 May 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Morrison 2016, p. 607.

- McClements, Freya (12 April 2018). "New dissident group issues execution threat to drug dealers". The Irish Times. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Morrison 2016, p. 608.

- Monaghan 2002, p. 49.

- Hamill 2011, pp. 134–135.

- McEvoy & Mika 2001, p. 364.

- Monaghan 2002, p. 50.

- Hamill 2011, p. 137.

- Monaghan 2002, pp. 46, 52.

- Brewer et al. 1998, p. 579.

- Feenan 2002b, p. 154.

- Monaghan 2002, p. 47.

- Silke 1998, p. 132.

- Hamill 2011, pp. 34, 69, 71.

- Peyton 2002, p. s54.

- Sarma 2013, p. 252.

- Monaghan 2002, p. 46.

- Hamill 2011, p. 69.

- Hamill 2011, pp. 76–77.

- Hamill 2011, pp. 70–71.

- Silke 1998, pp. 124, 131.

- Hamill 2011, pp. 72–73.

- Silke & Taylor 2002, p. 11.

- Barr & Mollan 1989, p. 740–741.

- McEvoy & Mika 2001, p. 360.

- Hamill 2011, p. 74.

- McGarry et al. 2017, p. 93.

- Lau et al. 2017, p. 747.

- Hamill 2011, pp. 74–75.

- Silke & Taylor 2002, p. 12.

- Knox & Dickson 2002, p. 2.

- "Brutality behind 'street justice'". BBC News. 16 February 2004. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Brogan, Benedict (15 June 2000). "Doctors told IRA how to carry out "punishment" acts". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Monaghan 2002, pp. 45, 50.

- Feenan 2002b, pp. 163–164.

- Hamill 2011, pp. 77–78.

- Hamill 2011, p. 79.

- Mallon et al. 2019, p. 4.

- "Terror attacks cost NHS £1.5m". BBC News. 3 September 2002. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- McGarry et al. 2017, p. 92.

- Munck 1984, p. 90.

- Lau et al. 2017, p. 750.

- Graham & Parke 2004, p. 229.

- Knox & Dickson 2002, pp. 10–11.

- Torney, Kathryn (22 March 2015). "Above the Law: 'Punishment' attacks in Northern Ireland". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Silke 2000, abstract.

- "Timeline of Irish dissident activity". BBC News. 10 September 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Knox 2002, pp. 174, 176.

- Mallon 2017, p. 3.

- Silke 1998, pp. 123–124.

- Forss, Alec (10 August 2016). "The enduring legacy of paramilitary punishment in Northern Ireland". Peace Insight. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Silke & Taylor 2002, p. 6.

- Silke & Taylor 2002, p. 7.

- Silke & Taylor 2002, pp. 6–8.

- Silke & Taylor 2002, p. 9.

- Silke & Taylor 2002, p. 10.

- Topping & Byrne 2012, p. 42.

- O'Doherty, Malachi (28 November 2019). "Thugs behind 'punishment' attacks act as if they enjoy some sort of community endorsement... shamefully, they're not wrong". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Hamill 2011, p. 98, passim.

- Jarman 2007, p. 8.

- Hamill 2002, pp. 67–68.

- Feenan 2002b, pp. 165–166.

- Silke 1998, p. 134.

- Ross 2012, p. 63.

- Feenan 2002b, pp. 164–165.

- Knox & Dickson 2002, pp. 6–7.

- Monaghan 2004, p. 441.

- Feenan 2002b, p. 166.

- Breen, Suzanne. "NI Presbyterian former minister dies of heart attack following beating". The Irish Times. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Dawson, Greg (20 November 2017). "I was shot in the knee as a punishment". BBC News. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Kilpatrick, Chris (11 November 2014). "A catalogue of brutality... by the thugs who shoot and beat children and then try to call it justice". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Verkaik, Robert (3 August 2018). "Police forces struggle to contain digital vigilante groups taking the law into their own hands". iNews. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Monaghan 2002, p. 48.

- Stevenson 1996, pp. 134–135.

- Knox 2001, p. 196.

- Stevenson 1996, p. 135.

- Cody 2008, p. 12.

- Madden, Andrew (27 June 2017). "PSNI clear 10 of 317 paramilitary-style 'punishment' attacks". The Irish News. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- Silke & Taylor 2002, pp. 12–13.

- Kearney, Vincent (27 September 2017). "New taskforce to tackle paramilitaries". BBC News. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Human Rights Watch 1997, 5. Paramilitary "Policing": Requirements of International Law.

- Conway 1997, pp. 109-110.

- McEvoy & Mika 2001, p. 368.

- Jarman 2007, pp. 11-12.

- McEvoy & Mika 2001, p. 369.

- McEvoy & Mika 2002, p. 537.

- Feenan 2002b, p. 167.

- Jarman 2007, p. 12.

- McEvoy & Mika 2002, p. 554.

- Jarman 2007, p. 13.

- Cody 2008, p. 556.

- McEvoy & Mika 2002, p. 552.

Sources

Books

- Brooks, Graham (2019). Criminal Justice and Corruption: State Power, Privatization and Legitimacy. Basingstroke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-030-16038-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Feenan, Dermot (2002a). "Community Justice in Conflict: Paramilitary Punishment in Northern Ireland". Informal Criminal Justice. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 41–60. ISBN 978-0-7546-2220-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gallaher, Carolyn (2011). After the Peace: Loyalist Paramilitaries in Post-Accord Northern Ireland. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-6158-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gormally, Sinéad (2014). "The Complexities, Contradictions and Consequences of Being 'Anti-social' in Northern Ireland". In Pickard, Sarah (ed.). Anti-Social Behaviour in Britain: Victorian and Contemporary Perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 179–191. ISBN 978-1-137-39931-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hamill, Heather (2002). "Victims of Paramilitary Punishment Attacks in Belfast". In Hoyle, Carolyn; Young, Richard (eds.). New Visions of Crime Victims. Oxford: Hart Publishing. pp. 49–69. ISBN 978-1-84113-280-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hamill, Heather (2011). The Hoods: Crime and Punishment in Belfast. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3673-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- To Serve Without Favor: Policing, Human Rights, and Accountability in Northern Ireland. Helsinki: Human Rights Watch. 1997. ISBN 978-1-56432-216-6.

- Jarman, Neil (2007). "Vigilantism, Transition and Legitimacy: Informal Policing in Northern Ireland". In Pratten, David; Sen, Atreyee (eds.). Global Vigilantes: Perspectives on Justice and Violence. London: Hurst. ISBN 978-1-85065-837-5. From an online reprint paginated 1–22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knox, Colin; Monaghan, Rachel (2002). Informal Justice in Divided Societies: Northern Ireland and South Africa. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-50363-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McEvoy, Kieran (2001). "Human Rights, Humanitarian Interventions and Paramilitary Activities in Northern Ireland". In Harvey, Colin J. (ed.). Human Rights, Equality and Democratic Renewal in Northern Ireland. Oxford: Hart. pp. 215–248. ISBN 978-1-84113-119-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moran, Jon (2009). Policing the Peace in Northern Ireland: Politics, Crime and Security After the Belfast Agreement. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-7471-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sarma, Kiran (2013). "The Use of Informants in Counterterrorism Operations: Lessons from Northern Ireland". In Lowe, David (ed.). Examining Political Violence: Studies of Terrorism, Counterterrorism and Internal War. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-8820-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spencer, Graham (2008). The State of Loyalism in Northern Ireland. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-58225-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Journals

- Barr, R J; Mollan, R A (1989). "The Orthopaedic Consequences of Civil Disturbance in Northern Ireland" (PDF). The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 71 (5): 739–744. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.71B5.2584241. PMID 2584241.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bradford, Ben; Topping, John; Martin, Richard; Jackson, Jonathan (2019). "Can Diversity Promote Trust? Neighbourhood Context and Trust in the Police in Northern Ireland" (PDF). Policing and Society. 29 (9): 1022–1041. doi:10.1080/10439463.2018.1479409. ISSN 1477-2728.

- Brewer, John D.; Lockhart, Bill; Rodgers, Paula (1998). "Informal Social Control and Crime Management in Belfast". The British Journal of Sociology. 49 (4): 570–585. doi:10.2307/591289. ISSN 0007-1315. JSTOR 591289.

- Cavanaugh, Kathleen A. (1997). "Interpretations of political violence in ethnically divided societies". Terrorism and Political Violence. 9 (3): 33–54. doi:10.1080/09546559708427414.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cody, Patrick (2008). "From Kneecappings toward Peace: The Use of Intra-Community Dispute Resolution in Northern Ireland". Journal of Dispute Resolution. 2008 (2). ISSN 1052-2859.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Conway, Pat (1997). "A Response to Paramilitary Policing in Northern Ireland". Critical Criminology. 8 (1): 109–121. doi:10.1007/BF02461139. ISSN 1572-9877.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Feenan, Dermot (2002b). "Justice in Conflict: Paramilitary Punishment in Ireland (North)". International Journal of the Sociology of Law. 30 (2): 151–172. doi:10.1016/S0194-6595(02)00027-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Graham, L. E.; Parke, R. C. (2004). "The Northern Ireland troubles and limb loss: a retrospective study". Prosthetics and Orthotics International. 28 (3): 225–229. doi:10.3109/03093640409167754. ISSN 0309-3646. PMID 15658635.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knox, Colin (2001). "The 'Deserving' Victims of Political Violence:: 'Punishment' Attacks in Northern Ireland" (doc). Criminal Justice. 1 (2): 181–199. doi:10.1177/1466802501001002003. ISSN 1466-8025.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knox, Colin (2002). "'See No Evil, Hear No Evil'. Insidious Paramilitary Violence in Northern Ireland" (PDF). British Journal of Criminology. 42 (1): 164–185. doi:10.1093/bjc/42.1.164.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lau, M.; McCain, S.; Baker, R.; Harkin, D. W. (2017). "Belfast Limb Arterial and Skeletal Trauma (BLAST): the evolution of punishment shooting in Northern Ireland". Irish Journal of Medical Science. 186 (3): 747–752. doi:10.1007/s11845-017-1561-8. ISSN 1863-4362. PMC 5550529. PMID 28110378.

- Mallon, Sharon; Galway, Karen; Rondon-Sulbaran, Janeet; Hughes, Lynette; Leavey, Gerry (2019). "Suicide in Post Agreement Northern Ireland: a Study of the Role of Paramilitary Intimidation 2007-2009". Suicidology Online. 10. ISSN 2078-5488.

- McCorry, Jim; Morrissey, Mike (1989). "Community, Crime and Punishment in West Belfast". The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice. 28 (4): 282–290. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2311.1989.tb00658.x. ISSN 1468-2311.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McEvoy, Kieran; Mika, Harry (2001). "Punishment, policing and praxis: Restorative justice and non‐violent alternatives to paramilitary punishments in Northern Ireland". Policing and Society. 11 (3–4): 359–382. doi:10.1080/10439463.2001.9964871. ISSN 1477-2728.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McEvoy, Kieran; Mika, Harry (2002). "Restorative Justice and the Critique of Informalism in Northern Ireland". The British Journal of Criminology. 42 (3): 534–562. doi:10.1093/bjc/42.3.534. ISSN 0007-0955. JSTOR 23638880.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McGarry, Kevin; Redmill, Duncan; Edwards, Mark; Byrne, Aoife; Brady, Aaron; Taylor, Mark (2017). "Punishment Attacks in Post-Ceasefire Northern Ireland: An Emergency Department Perspective". The Ulster Medical Journal. 86 (2): 90–93. ISSN 0041-6193. PMC 5846011. PMID 29535478.

- Monaghan, Rachel (2002). "The Return of "Captain Moonlight": Informal Justice in Northern Ireland". Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. 25 (1): 41–56. doi:10.1080/105761002753404140. ISSN 1057-610X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Monaghan, Rachel (2004). "'An Imperfect Peace': Paramilitary 'Punishments' in Northern Ireland". Terrorism and Political Violence. 16 (3): 439–461. doi:10.1080/09546550490509775. ISSN 0954-6553.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morrison, John F. (2016). "Fighting Talk: The Statements of "The IRA/New IRA"" (PDF). Terrorism and Political Violence. 28 (3): 598–619. doi:10.1080/09546553.2016.1155941. ISSN 1556-1836.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morrissey, Michael; Pease, Ken (1982). "The Black Criminal Justice System in West Belfast". The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice. 21 (1–3): 159–166. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2311.1982.tb00461.x. ISSN 1468-2311.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Munck, Ronnie (1984). "Repression, Insurgency, and Popular Justice: The Irish Case". Crime and Social Justice (21/22): 81–94. ISSN 0094-7571. JSTOR 29766231.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mullins, Sam; Wither, James K. (2016). "Terrorism and Organized Crime". Connections. 15 (3): 65–82. doi:10.11610/Connections.15.3.06. ISSN 1812-1098. JSTOR 26326452.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Napier, Richard J.; Gallagher, Brendan J.; Wilson, Darrin S. (2017). "An Imperfect Peace: Trends In Paramilitary Related Violence 20 Years After The Northern Ireland Ceasefires". The Ulster Medical Journal. 86 (2): 99–102. ISSN 2046-4207. PMC 5846013. PMID 29535480.

- Peyton, Rodney (2002). "Punishment beatings and the rule of law". The Lancet. 360 (Special Issue 1): s53–s54. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11822-8. PMID 12504505.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ross, F. Stuart (2012). "It Hasn't Gone Away You Know: Irish Republican Violence in the Post-Agreement Era". Nordic Irish Studies. 11 (2): 55–70. ISSN 1602-124X. JSTOR 41702636.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silke, Andrew (1998). "The Lords of Discipline: The Methods and Motives of Paramilitary Vigilantism in Northern Ireland". Low Intensity Conflict & Law Enforcement. 7 (2): 121–156. ISSN 1744-0556.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silke, Andrew (1999a). "Rebel's Dilemma: The Changing Relationship Between the IRA, Sinn Féin and Paramilitary Vigilantism in Northern Ireland". Terrorism and Political Violence. 11 (1): 55–93. doi:10.1080/09546559908427495. ISSN 0954-6553.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silke, Andrew (1999b). "Ragged Justice: Loyalist Vigilantism in Northern Ireland". Terrorism and Political Violence. 11 (3): 1–31. doi:10.1080/09546559908427514. ISSN 0954-6553.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silke, Andrew (2000). "The Impact of Paramilitary Vigilantism on Victims and Communities in Northern Ireland". The International Journal of Human Rights. 4 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1080/13642980008406857. ISSN 1364-2987.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silke, Andrew; Taylor, Max (2002). "War Without End: Comparing IRA and Loyalist Vigilantism in Northern Ireland". The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice . 39 (3): 249–266. doi:10.1111/1468-2311.00167. ISSN 0265-5527. From an online reprint paginated 1–14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Steenkamp, Christina (2008). "Loyalist Paramilitary Violence after the Belfast Agreement". Ethnopolitics. 7 (1): 159–176. doi:10.1080/17449050701847285.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Steinberg, James M. (2019). "The Good Friday Agreement: Ending War and Ending Conflict in Northern Ireland". Texas National Security Review. 2 (3): 78–102. doi:10.26153/tsw/2926. ISSN 2576-1153.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stevenson, Jonathan (1996). "Northern Ireland: Treating Terrorists as Statesmen". Foreign Policy (105): 125–140. doi:10.2307/1148978. ISSN 0015-7228. JSTOR 1148978.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Topping, John; Byrne, Jonny (2012). "Paramilitary Punishments in Belfast: Policing Beneath the Peace". Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression. 4 (1): 41–59. doi:10.1080/19434472.2011.631349. ISSN 1943-4472.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Other

- Kennedy, Liam (2001). "'They Shoot Children Don't They?: An Analysis of the Age and Gender of Victims of Paramilitary "Punishments" in Northern Ireland'". Report to the Northern Ireland Committee Against Terror and the House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Knox, Colin; Dickson, Brice (2002). An evaluation of the alternative criminal justice system in Northern Ireland: Full Report of Research Activities and Results (Grant L133251003) (Report). Economic and Social Research Council.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mallon, Sharon (2017). The Role of Paramilitary Punishment Attacks and Intimidation in Death by Suicide in Post Agreement Northern Ireland (PDF). Knowledge Exchange Seminar Series 2016-17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Murphy, Joanne (2009). RUC to PSNI: a Study of Radical Organisational Change (PhD thesis). Trinity Business School (Trinity College Dublin).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Bell, Christine (1996). "Alternative Justice in Ireland". In Dawson, Norma; Greer, Desmond; Ingram, Peter (eds.). One Hundred and Fifty Years of Irish Law. SLS Legal Publications. pp. 145–167. ISBN 978-0-85389-615-9.

- Kennedy, Liam (1995). Nightmares within Nightmares: Paramilitary Repression within Working Class Communities. Crime and Punishment in West Belfast. Belfast: Summer School. ISBN 978-0-85389-588-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Munck, Ronaldo (1988). "The Lads and the Hoods: Alternative Justice in an Irish Context". In Tomlinson, Mike; McCullagh, Ciaran; Varley, Tony (eds.). Whose Law and Order? Aspects of Crime and Social Control in Irish Society. Sociological Association of Ireland : Distributed by Queen's University Bookshop Ltd. ISBN 978-0-9513411-0-0.

External links

- Ending the Harm, official campaign against punishment attacks

- Interactive map of punishment attacks 1990–2014, by RTÉ

- 2018 BBC documentary on punishment attacks, by Stacey Dooley