Paraiyar

Paraiyar[1] or Parayar[2] or Maraiyar or Sambavar (formerly anglicised as Pariah and Paree[3]) is a caste group found in the Indian states of Tamil Nadu and Kerala and Sri Lanka.[4] The Adi Dravida ("Ancient Dravidians") are an unrelated caste which didn't have connotations of lawlessness in British and European chroniclers.[5]

| Paraiyar | |

|---|---|

| Adi Dravidar | |

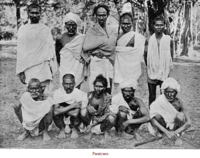

Group of Paraiyars in the Madras Presidency, 1909 | |

| Religions | |

| Languages | Tamil |

| Country | |

| Populated states | Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Puducherry |

| Ethnicity | Tamils |

| Population | 9,462,985 |

| Related groups | Tamils • Sri Lankan Paraiyar |

| Status | SC |

The 2011 Census of India reported that in Tamil Nadu the Paraiyar and Adi Dravidar population was 9,064,700, at around 12% of total population of the Tamil Nadu.[6][7] The texts and accounts written during British rule put them at 2% to 5% of the general population, although it could be an observational bias.

Etymology

Robert Caldwell and several other writers derive the name of the community from the Tamil word parai ("drum"). According to this hypothesis, the Paraiyars were originally a community of drummers who performed during flood time, war, auspicious events like festivals, weddings and also funerals.[8] As their population increased, they were forced to take up occupations that were considered unclean, such as burial of corpses and scavenging. Because of this, they came to be considered an untouchable caste. M. Srinivasa Aiyangar finds this etymology unsatisfactory, arguing that beating of drums could not have been an occupation of many people. Some other writers, such as Gustav Solomon Oppert, derive the name from poraian, the name of a regional subdivision mentioned by ancient Tamil grammarians.[9] During the period of Rajaraja I, since Paraicheri (Paraiyar hamlet) is mentioned separately and in addition to Teendacheri (untouchable hamlet) in epigraphs, it is believed that the untouchables were different from the Paraiyars during those times.[10]

History

Pre-British period

The Sangam literature (c. 300 BCE–300 CE) contains references to the caste system of Tamil culture, which contained a number of "low-born" groups referred to variously as Pulaiyar and Kinaiyar. They were believed to be associated with magical power and kept at a distance, made to live in separate hamlets outside villages. However, their magical power was believed to sustain the king, who had the ability to transform it into auspicious power. George L. Hart believes that one of the drums called kiṇai later came to be called paṟai and the people that played the drum were paṟaiyar (plural of paṟaiyan).[11][12] Thus the pulaiyar performed a ritual function by composing and singing songs in the king's favour and beating drums. They were divided into subgroups based on the instruments they played.

The Sangam literature also quotes the Paraiyars as being farmers and rulers. They were referred to as Eiyinars .The word "Eiyinar" refers to those who built Eiyils (fortresses). As the Paraiyas were experts in the art of building fortifications, they may well have earned this name. It is also mentioned that the Paraiyars had their own priests, carpenters, shoe-makers, weavers, washer men, and hair dressers.[13]

The earliest extant reference to the term Paraiyar (as an occupational term for drummers) occurs in a poem by the Sangam poet Mangudi Kilar (2nd century CE). But the earliest mention of the term as a caste does not occur until the reign of Rajaraja Chola (11th century CE).[14] From this period onwards, the word occurs in different contexts in the various pre-British sources. There is every reason to believe that the status of the Paraiyars was not much different from any of the other cultivating castes during the period of Rajaraja I.

- Inscriptions, especially those from the Thanjavur district, mention paraicceris, which were separate hamlets of the Paraiyars.[15] Also living in separate hamlets were the artisans such as goldsmiths and cobblers, who were also accorded low status in the Sangam literature.[16]

- In a few inscriptions (all of them from outside Thanjavur district), Paraiyars are described as temple patrons.[15]

- There are also references to "Paraiya chieftainships" in the 8th and 10th centuries, but it is not known what these were and how they were integrated into the Chola political system.[16]

- The Thanjavur inscriptions mention a number of villages where Paraicheri and Teendacheri were located. In all these instances, it is found that these colonies, i.e., the Paraicheris and Teendacheris were exempted from paying tax (land).[17]

- In another epigraph, since Paraicheri is mentioned separately and in addition to Teendacheri, it is believed that the untouchables were different from the Paraiyars.[18]

- The Paraiyar settlements were near agricultural lands and irrigation channels. In Chola epigraphs, the Paraiyars are called ulaparaiyars, that is Paraiyars who were engaged in cultivation. An inscription of Rajaraja mentions that ulaparaiyars occupied kilacheri and melaparaicheri in Venkondi village.[19]

Burton Stein describes an essentially continuous process of expansion of the nuclear areas of the caste society into forest and upland areas of tribal and warrior people, and their integration into the caste society at the lowest levels. Many of the forest groups were incorporated as Paraiyar either by association with the parai drum or by integration into the low-status labouring groups who were generically called Paraiyar. Thus, it is thought that Paraiyar came to have many subcastes.[20]

During the Bhakti movement (c. 7th–9th centuries CE), the saints - Shaivite Nayanars and the Vaishnavite Alvars - contained one saint each from the untouchable communities. The Nayanar saint Nandanar was born, according to Periya Puranam, in a "threshold of the huts covered with strips of leather", with mango trees from whose branches were hung drums. "In this abode of the people of the lowest caste (kadainar), there arose a man with a feeling of true devotion to the feet of Siva." Nandanar was described as a temple servant and leather worker, who supplied straps for drums and gut-string for stringed instruments used in the Chidambaram temple, but he was himself not allowed to enter the temple.[21] The Paraiyar regard Nandanar as one of their own caste.[22] Paraiyars wear the sacred thread under rituals such as marriage and funeral.[23]

Scholars such as Burchett and Moffatt state that the Bhakti devotationalism did not undermine Brahmin ritual dominance. Instead, it might have strengthened it by warding off challenges from Jainism and Buddhism.[24][25]

The Sri Lankan Paraiyars, under the Jaffna kings, were traditional weavers and heralds. Some of them also practised native medicine and astrology.[26]

British colonial era

By the early 19th century, the Paraiyars had a degraded status in the Tamil society.[27] Francis Buchanan's report on socio-economic condition of South Indians described them ("Pariar") as inferior caste slaves, who cultivated the lands held by Brahmins. This report largely shaped the perceptions of the British officials about contemporary society. They regarded Pariyars as an outcaste, untouchable community.[28] In the second half of the 19th century, there were frequent descriptions of the Paraiyars in official documents and reformist tracts as being "disinherited sons of the earth".[29][30] The first reference to the idea may be that written by Francis Whyte Ellis in 1818, where he writes that the Paraiyars "affect to consider themselves as the real proprietors of the soil". In 1894, William Goudie, a Weslyan missionary, said that the Paraiyars were self-evidently the "disinherited children of the soil".[30] English officials such as Ellis believed that the Paraiyars were serfs toiling under a system of bonded labour that resembled the European villeinage.[31] However, scholars such as Burton Stein argue that the agricultural bondage in Tamil society was different from the contemporary British ideas of slavery.[32]

Historians such as David Washbrook have argued that the socio-economic status of the Paraiyars rose greatly in the 18th century during the Company rule in India; Washbrook calls it the "Golden Age of the Pariah".[33] Raj Sekhar Basu disagrees with this narrative, although he agrees that there were "certain important economic developments".[34]

The Church Mission Society converted many Paraiyars to Christianity by the early 19th century.[35] During the British Raj, the missionary schools and colleges admitted Paraiyar students amid opposition from the upper-caste students. In 1893, the colonial government sanctioned an additional stipend for the Paraiyar students.[36] The colonial officials, scholars, and missionaries attempted to rewrite the history of the Paraiyars, characterising them as a community that enjoyed a high status in the past. Edgar Thurston (1855-1935), for example, claimed that their status was nearly equal to that of the Brahmins in the past.[37] H. A. Stuart, in his Census Report of 1891, claimed that Valluvans were a priestly class among the Paraiyars, and served as priests during Pallava reign. Robert Caldwell, J. H. A. Tremenheere and Edward Jewitt Robinson claimed that the ancient poet-philosopher Thiruvalluvar was a Paraiyar.[38]

Buddhist advocacy by Iyothee Thass

Iyothee Thass, a Siddha doctor by occupation, belonged to a Paraiyar elite. In 1892, he demanded access for Paraiyars to Hindu temples, but faced resistance from upper-caste Brahmins and Vellalars. This experience led him to believe that it was impossible to emancipate the community within the Hindu fold. In 1893, he also rejected Christianity and Islam as the alternatives to Hinduism, because caste differences had persisted among Indian Christians, while the backwardness of contemporary local Muslims made Islam unappealing.[39]

Thass subsequently attempted a Buddhist reconstruction of the Tamil religious history. He argued that the Paraiyars were originally followers of Buddhism and constituted the original population of India. According to him, the Brahmanical invaders from Persia defeated them and destroyed Buddhism in southern India; as a result, the Paraiyars lost their culture, religion, wealth and status in the society and become destitute. In 1898, Thass and many of his followers converted to Buddhism and founded the Sakya Buddha Society (cākkaiya putta caṅkam) with the influential mediation of Henry Steel Olcott of the Theosophical Society. Olcott subsequently and greatly supported the Tamil Paraiyar Buddhists.[40]

Controversy over the community's name

Iyothee Thass felt that Paraiyar was a slur, and campaigned against its usage. During the 1881 census of India, he requested the government to record the community members under the name Aboriginal Tamils. He later suggested Dravidian as an alternative term, and formed the Dhraavidar Mahajana Sabhai (Dravidian Mahajana Assembly) in 1891. Another Paraiyar leader, Rettamalai Srinivasan, however, advocated using the term Paraiyar with pride. In 1892, he formed the Parayar Mahajana Sabha (Paraiyar Mahajana Assembly), and also started a news publication titled Paraiyan.[41]

Thass continued his campaign against the term, and petitioned the government to discontinue its usage, demanding punishment for those who used the term. He incorrectly claimed that the term Paraiyar was not found in any ancient records (it has been, in fact, found in the 10th century Chola stone inscriptions from Kolar district).[41] Thass subsequently advocated the term Adi Dravida (Original Dravidians) to describe the community. In 1892, he used the term Adidravida Jana Sabhai to describe an organisation, which was probably Srinivasan's Parayar Mahajana Sabha. In 1895, he established the People’s Assembly of Urdravidians (Adidravida Jana Sabha), which probably split off from Srinivasan's organisation. According to Michael Bergunder, Thass was thus the first person to introduce the concept of Adi Dravida into political discussion.[42]

Another Paraiyar leader, M. C. Rajah — a Madras councillor — made successful efforts for adoption of the term Adi-Dravidar in the government records.[41] In 1914, the Madras Legislative Council passed a resolution that officially censured the usage of the term Paraiyar to refer to a specific community, and recommended Adi Dravidar as an alternative.[43] In the 1920s and 1930s, Periyar E. V. Ramasamy ensured the wider dissemination of the term Adi Dravida.[42]

Right-hand caste faction

Paraiyars belong to the Valangai ("Right-hand caste faction"). Some of them assume the title Valangamattan ("people of the right-hand division"). The Valangai comprised castes with an agricultural basis while the Idangai consisted of castes involved in manufacturing.[44] Valangai, which was better organised politically.[45]

Notable people

Religious and spiritual leaders

- Poykayil Yohannan,[46] rejected Christianity and Hinduism to found the Prathyaksha Raksha Daiva Sabha

Social reformers and activists

- M. C. Rajah, (1883–1943) Politician, social and political activist from the Indian state of Tamil Nadu[41]

- Rettamalai Srinivasan (1860–1945), Dalit activist, politician from Tamil Nadu[47]

- Iyothee Thass (1845–1914), founder of the Sakya Buddhist Society (also known as Indian Buddhist Association)[30]

References

Citations

- Raman, Ravi (2010). Global Capital and Peripheral Labour: The History and Political Economy of Plantation Workers in India. Routledge. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-13519-658-5.

- Gough, Kathleen (2008) [1981]. Rural Society in Southeast India. Cambridge University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-52104-019-8.

- Fontaine, Petrus Franciscus Maria (1990). The Light and the Dark: Dualism in ancient Iran, India, and China. Brill Academic Pub. p. 100. ISBN 9789050630511.

- McGilvray, Dennis B. (1983). "Paraiyar Drummers of Sri Lanka: consensus and constraint in an untouchable caste" (PDF). American Ethnologist. 10 (1): 97–115. doi:10.1525/ae.1983.10.1.02a00060.

- Irschick (1994), pp. 168-169.

- "Tamil Nadu — Data Highlightst: The Scheduled Castes — Census of India 2001" (PDF). p. 1. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- (PDF) http://www.censusindia.gov.in/Tables_Published/SCST/dh_sc_tamilnadu.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Krishnamachari, Suganthy (3 January 2013). "Secular and sacred". The Hindu. Retrieved 11 April 2018 – via www.thehindu.com.

- Basu (2011), pp. 2-3.

- Krishnaswamy Ranaganathan Hanumanthan. Untouchability: A Historical Study Upto 1500 A.D. : with Special Reference to Tamil Nadu. Koodal Publishers, 1979. p. 162.

- Hart, George L. (1987). "Early Evidence for Caste in South India". In Hockings, Paul (ed.). Dimensions of Social Life: Essays in honor of David B. Mandelbaum. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 468. ISBN 978-3-11084-685-0.

"The kiṇaiyan seems to have been a bit lower than the Pāṇan. He would beat a small drum called a kiṇai, praise the king in the morning or at other times, receiving some reward for that act, and, evidently, he would go from village to village announcing the king’s decrees. He was probably the same as the modern Paṟaiyan.

- Moffatt (1979), pp. 36-37.

- Iyengar, M.Srinivasa (1998). Tamil Studies. Madras : Guardian press. p. 81. ISBN 8120600290.

- Basu (2011), p. 3.

- Orr (2000), pp. 236-237.

- Moffatt (1979), p. 38.

- Irāmaccantiran̲ Nākacāmi. Studies in Ancient Tamil Law and Society, Issue 47 of T.N.S.D.A. publication, Tamil Nadu (India). Dept. of Archaeology. Institute of Epigraphy, State Department of Archaeology, Government of Tamilnadu, 1978. p. 100.

- Krishnaswamy Ranaganathan Hanumanthan. Untouchability: A Historical Study Upto 1500 A.D. : with Special Reference to Tamil Nadu. Koodal Publishers, 1979. p. 162.

- "Epigraphical Society of India". Journal of the Epigraphical Society of India, Volume 25. The Society, 1999. p. 95.

- Moffatt (1979), p. 41.

- Moffatt (1979), pp. 38-39.

- Vincentnathan, Lynn (June 1993). "Nandanar: Untouchable Saint and Caste Hindu Anomaly". Ethos. 21 (2): 154–179. doi:10.1525/eth.1993.21.2.02a00020. JSTOR 640372.

- Kolappa Pillay, Kanakasabhapathi (1977). The Caste System in Tamil Nadu. University of Madras. p. 33.

- Moffatt (1979), p. 39.

- Burchett, Patton (August 2009). "Bhakti Rhetoric in the Hagiography of 'Untouchable' Saints: Discerning Bhakti's Ambivalence on Caste and Brahminhood". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 13 (2): 115–141. doi:10.1007/s11407-009-9072-5. JSTOR 40608021.

- Ragupathy, Ponnampalam (1987). Early Settlements in Jaffna: An Archaeological Survey. University of Jaffna: Thillimalar Ragupathy. p. 210.

- Basu (2011), p. 16.

- Basu (2011), pp. 2.

- Irschick (1994), pp. 153–190.

- Bergunder (2004), p. 68.

- Basu (2011), pp. 9-11.

- Basu (2011), pp. 4.

- Basu (2011), pp. 33-34.

- Basu (2011), p. 39.

- Kanjamala (2014), p. 127.

- Kanjamala (2014), p. 66.

- Basu (2011), pp. 24-26.

- Moffatt (1979), p. 19-21.

- Bergunder (2004), p. 70.

- Bergunder (2004), pp. 67-71.

- Srikumar (2014), p. 357.

- Bergunder (2004), p. 69.

- Bergunder, Frese & Schröder (2011), p. 260.

- Siromoney, Gift (1975). "More inscriptions from the Tambaram area". Madras Christian College Magazine. 44. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- Levinson, Stephen C. (1982). "Caste rank and verbal interaction in western Tamilnadu". In McGilvray, Dennis B. (ed.). Caste Ideology and Interaction. Cambridge Papers in Social Anthropology. 9. Cambridge University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-52124-145-8.

- Mylapore Institute for Indigenous Studies; I.S.P.C.K. (Organisation) (2000). Christianity is Indian: the emergence of an indigenous community. Published for MIIS, Mylapore by ISPCK. p. 322. ISBN 978-81-7214-561-3.

- Srikumar (2014), p. 356.

Bibliography

- Basu, Raj Sekhar (2011), Nandanar's Children: The Paraiyans' Tryst with Destiny, Tamil Nadu 1850 - 1956, SAGE, ISBN 978-81-321-0679-1CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bergunder, Michael (2004), "Contested Past: Anti-brahmanical and Hindu nationalist reconstructions of early Indian history" (PDF), Historiographia Linguistica, 31 (1): 95–104, doi:10.1075/hl.31.1.05berCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bergunder, Michael; Frese, Heiko; Schröder, Ulrike, eds. (2011), Ritual, Caste, and Religion in Colonial South India, Primus Books, ISBN 978-93-80607-21-4

- Irschick, Eugene F. (1994), Dialogue and History: Constructing South India, 1795–1895, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 9780520914322

- Kanjamala, Augustine (2014), The Future of Christian Mission in India, Wipf and Stock, ISBN 978-1-63087-485-8CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moffatt, Michael (1979), An Untouchable Community in South India: Structure and Consensus, Princeton University Press, pp. 37–, ISBN 978-1-4008-7036-3

- Orr, Leslie C. (2000), Donors, Devotees, and Daughters of God, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-535672-4CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Srikumar, S (2014), Kolar Gold Field: (Unfolding the Untold), Partridge Publishing India, ISBN 978-1-4828-1507-8CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)