Pan Am Flight 214

Pan Am Flight 214 was a scheduled flight of Pan American World Airways from San Juan, Puerto Rico, to Baltimore, Maryland, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. On December 8, 1963, the Boeing 707 serving the flight crashed near Elkton, Maryland, while flying from Baltimore to Philadelphia, after being hit by lightning. All 81 occupants of the plane were killed. It was the first fatal accident on a Pan Am jet aircraft since the company had taken its first delivery of the type five years earlier.

The aircraft involved in the crash, N709PA, before being delivered to Pan Am | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | December 8, 1963 |

| Summary | In-flight explosion and break up caused by lightning strike |

| Site | Elkton, Maryland, United States 39°36′47.8″N 75°47′29.7″W |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 707-121 |

| Aircraft name | Clipper Tradewind |

| Operator | Pan American World Airways |

| Registration | N709PA |

| Flight origin | Isla Verde International Airport |

| Stopover | Friendship Airport |

| Destination | Philadelphia Int'l Airport |

| Occupants | 81 |

| Passengers | 73 |

| Crew | 8 |

| Fatalities | 81 |

| Survivors | 0 |

An investigation by the Civil Aeronautics Board concluded that the cause of the crash was a lightning strike that had ignited fuel vapors in one of the aircraft's fuel tanks, causing an explosion that destroyed one of the wings. The exact way that the lightning had ignited the fumes was never determined. However, the investigation revealed various ways that lightning can damage aircraft in flight, which led to new safety regulations. The crash also led to research into the safety of different types of aviation fuel and research into methods of reducing dangerous fuel-tank vapors.

Accident

Pan American Flight 214 was a regularly scheduled flight from Isla Verde International Airport in San Juan, Puerto Rico, to Philadelphia International Airport with a scheduled stopover at Baltimore's Friendship Airport.[1](p2) It operated three times a week as the counterpart to Flight 213, which flew from Philadelphia to San Juan via Baltimore earlier the same day.[2] Flight 214 left San Juan at 4:10 p.m. Eastern time with 140 passengers and 8 crew members, and arrived in Baltimore at 7:10 p.m.[1](p2)[3] The crew did not report any maintenance issues or problems during the flight.[1](p2) Upon arrival, 67 of the passengers disembarked in Baltimore.[3] After refueling, the aircraft left Baltimore at 8:24 p.m. with the remaining 73 passengers for the final leg to Philadelphia International Airport.[1](p2)[3]

As the flight approached Philadelphia, the pilots established contact with air traffic control near Philadelphia at 8:42 p.m. The controller informed the pilots that the airport was experiencing a line of thunderstorms in the vicinity of the airport, accompanied by strong winds and turbulence.[1](p3) The controller asked if the pilots wanted to proceed directly to the airport, or to enter a holding pattern to wait for the storm to pass.[1](p3) The crew of Pan Am flight 214 elected to hold, at 5,000 feet, in a holding pattern with five other aircraft.[4] The air traffic controller told them that the delay would be approximately 30 minutes.[1](p3) There was heavy rain in the holding area, with frequent lightning and gusts of wind up to fifty miles per hour (80 km/h).[5]

At 8:58 p.m., the aircraft exploded.[6] The pilots were able to transmit a final message, "MAYDAY MAYDAY MAYDAY. Clipper 214 out of control. Here we go."[7] Seconds later, the first officer of National Airlines Flight 16, holding 1,000 feet higher in the same holding pattern, radioed in, "Clipper 214 is going down in flames".[7] The aircraft crashed at 8:59 p.m. in a corn field east of Elkton, Maryland, near the Delaware Turnpike, setting the rain-soaked field on fire.[1](pp1, 3)[5] The aircraft was completely destroyed, and all of the occupants were killed.[1](p1)

The aircraft was the first Pan American jet plane to crash in the five years they had been flown by the airline.[5]

Aftermath

A Maryland State Trooper had been patrolling on Route 213 and he radioed an alert as he drove toward the crash site, east of Elkton near the state line. The Trooper was first to arrive at the crash site and later stated that “It wasn’t a large fire. It was several smaller fires. A fuselage with about 8 or 10 window frames was about the only large recognizable piece I could see when I pulled up. It was just a debris field. It didn’t resemble an airplane. The engines were buried in the ground 10 to 15-feet from the force of the impact.” [8][9]

The emergency radio communications tape from that evening was preserved, recording the early minutes of the accident as police officers and firefighters arrived at the scene. The streaming audio is available on the blog, A Window on Cecil County's Past

It was soon obvious to firefighters and police officers that there was a little could be done done other than begin the collection of bodies.[5] The wreckage was engulfed in intense fires that burned for more than four hours.[10] First responders and police from across the county, along with men from the Bainbridge Naval Training Center assisted with the recovery.[11] They patrolled the area with railroad flares and set up searchlights to define the accident scene and to make sure that the debris and human remains were undisturbed by curious spectators.[10][12]

Remains of the victims were brought to the National Guard Armory in Philadelphia where a temporary morgue was set up.[13] Relatives came to the armory, but officials there ruled out any possibility of being able to visually identify the victims.[13] It took the state medical examiner nine days to identify all of the victims, using fingerprints, dental records, and nearby personal effects.[11] In some cases, the team reconstructed the victims' faces as much as possible using mannequins.[11]

The main impact crater contained most of the aircraft's fuselage, the left inner wing, the left main gear, and the nose gear.[1](p5) Portions of the plane's right wing and fuselage, right main landing gear, horizontal and vertical tail surfaces, and two of the engines were found within 360 feet (110 m) of the crater.[1](p4) A trail of debris from the plane extended as far as four miles (6 km) from the point of impact.[1](p4) The complete left wing tip was found a little under two miles (3 km) from the crash site.[1](pp5–6) Parts of the wreckage ripped a 40-foot-wide (12 m) hole in a country road, shattered windows in a nearby home, and spread burning jet fuel across a wide area.[5][3]

The Civil Aeronautics Board was notified of the accident and was dispatched from Washington, D.C., to conduct an investigation.[1](p14)[5] Witnesses of the crash described hearing the explosion and seeing the plane in flames as it went down.[5] Of the 140 witnesses interviewed, 99 reported seeing an aircraft or a flaming object in the sky.[1](p4) Seven witnesses stated that they saw lightning strike the aircraft.[1](p4) Seventy-two witnesses said the ball of fire occurred at the same time or immediately after the lightning strike.[1](p4) Twenty-three witnesses reported that the aircraft exploded after they saw the plane on fire.[1](p4)

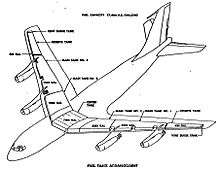

Aircraft

The aircraft involved was a Boeing 707-121 registered with tail number N709PA.[6] Named the Clipper Tradewind, it was the oldest aircraft in the U.S. commercial jet fleet at the time of the crash.[3][6] It had been delivered to Pan Am on 27 October 1958 and had flown a total of 14,609 hours.[1](p14) It was powered by four Pratt & Whitney JT3C-6 turbojet engines. At the time of the accident, the aircraft was estimated to have a book value of $3,400,000 (equivalent to $28,400,000 in 2019).[14]

Nearly five years earlier, in 1959, the same aircraft had been involved in an incident when the right outboard engine had been torn from the wing during a training flight in France. The plane entered a sudden spin during a demonstration of the aircraft's minimum control speed, and the aerodynamic forces caused the engine to break away.[15] The pilot regained control of the aircraft and landed safely in London using the remaining three engines.[15] The detached engine fell into a field on a farm southwest of Paris, where the flight had originated, with no injuries.[15]

Passengers and crew

The plane carried 73 passengers, who all died in the crash.[1](p1) All the passengers were residents of the United States.[16]

The pilot of the plane was George F. Knuth, 45, of Long Island.[16] He had flown for Pan Am for 22 years and had accumulated 17,049 hours of flying experience, including 2,890 in the Boeing 707.[11] He had been involved in another incident in 1949, when as pilot of Pan Am Flight 100, a Lockheed Constellation in flight over Port Washington, New York, a Cessna 140 single-engine airplane crashed into his plane. The two occupants of the Cessna were killed in the accident, but Captain Knuth was able to land safely with no injuries to the crew or passengers of the Pan Am flight.[17][18]

The first officer of the flight was John R. Dale, 48, of Long Island.[16] He had a total of 13,963 hours of flying time, of which 2,681 were in the Boeing 707.[1](p14) The second officer was Paul L. Orringer, age 42, of New Rochelle, New York.[16] He had 10,008 hours of flying experience, including 2,808 in Boeing 707 aircraft.[1](p14) The flight engineer was John R. Kantlehner, of Long Island.[16] He had a total flying time of 6,066 hours, including 76 hours in the Boeing 707.[1](p14)

Investigation

The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) assigned more than a dozen investigators within an hour of the crash.[3] They were assisted by investigators from the Boeing Company, Pan American World Airways, the Air Line Pilots Association, Pratt & Whitney, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Federal Aviation Agency.[3] The costs of investigations by the CAB at the time rarely exceeded $10,000, but the agency would spend about $125,000 investigating this crash (equivalent to $1,040,000 in 2019), in addition to the money spent by Boeing, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the engine manufacturer, and other aircraft parts suppliers on additional investigations.[19](p31)

Initial theories of the cause of the crash focused on the possibility that the plane had experienced severe turbulence in flight that had caused a fuel tank or fuel line to rupture, leading to an in-flight fire from leaking fuel.[3][20] U.S. House Representative Samuel S. Stratton of Schenectady, New York, sent a telegram to the Federal Aviation Administration urging them to restrict jet operations in turbulent weather, but the FAA responded that it saw no pattern that suggested the need for such restrictions, and the Boeing Company concurred.[20] Other possibilities of the cause of the crash included sabotage or that the aircraft had been hit by lightning, but by nightfall after the first day, investigators had not found evidence of either.[3] There was also some speculation that metal fatigue as a result of the aircraft's 1959 incident could be involved in the crash, but the aircraft had gone through four separate maintenance overhauls since the accident without any issues being detected.[3]

Investigators rapidly located the flight data recorder, but it was badly damaged in the crash.[3][21] Built to withstand an impact 100 times as strong as the force of gravity, it had been subjected to a force of 200 times the force of gravity, and its tape appeared to be hopelessly damaged.[19](p32) Alan S. Boyd, chairman of the CAB, told reporters shortly after the accident, "It was so compacted there is no way to tell at this time whether we can derive any useful information from it."[21] Eventually, investigators were able to extract data from 95 percent of the tape that had been in the recorder.[1](p8)

The recovery of the wreckage took place over a period of 12 days, and 16 truckloads of the debris was taken to Bolling Air Force Base in Washington, D.C., for investigators to examine and reassemble.[11] Investigators revealed that there was evidence of a fire that occurred in flight, and one commented that it was nearly certain that there had been an explosion of some kind before it crashed.[21] Eyewitness testimony later confirmed that the plane had been burning on its way down to the crash site.[22]

Within days, investigators reported that it was apparent that the crash had been caused by an explosion that had blown off one of the wing tips of the airplane.[23] The wing tip had been found about three miles (5 km) from the crash site bearing burn marks and bulging from an apparent internal explosive force.[23] Remnants of nine feet (3 m) of the wing tip had been found at various points along the flight path short of the impact crater.[23] Investigators revealed that it was unlikely that rough turbulence had caused the crash because the crews of other aircraft that had been circling in the area reported that the air was relatively smooth at the time.[23] They also said that the plane would have had to dive a considerable distance before aerodynamic forces would have caused it to break up and explode, but it was apparent that the aircraft had caught fire near its cruising altitude of 5,000 feet.[23]

Before this flight, there had been no other known case of lightning causing a plane to crash despite many instances of planes being struck.[23] Investigators found that on average, each airplane is struck by lightning once or twice a year.[24] Scientists and airline industry representatives vigorously disputed the theory that lightning could have caused the aircraft to explode, calling it improbable.[11] The closest example of such an instance occurred near Milan, Italy, in June 1959 where a Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation crashed as a result of static electricity igniting fuel vapor coming from the fuel vents.[23] Despite the opposition, investigators found multiple lightning strike marks on the left wing tip, and a large area of damage that extended along the rear edge of the wing, leading investigators to believe that lightning was the cause.[19](p34) The CAB launched an urgent research program in an attempt to identify conditions in which fuel vapors in the wings could have been ignited by lightning.[23] Within a week of the crash, the FAA issued an order requiring the installation of static electricity dischargers on the approximately 100 Boeing jet airliners that had not already been equipped with them.[19](p22)[25] Aviation industry representatives were critical of the order, saying there was no evidence that the dischargers would have any beneficial effect since they were never designed to handle the effects of lightning, and they said the order would create a false impression that the risk of lightning strikes had been resolved.[25]

The CAB conducted a public hearing in Philadelphia in February 1964 as part of their investigation.[1](p14) Experts had still not concluded that lightning had caused the accident, but they were investigating different ways lightning could have triggered the explosion.[26] The FAA said that it was going to conduct research to determine the relative safety of the two types of jet fuel used in the United States, both of which were present in the fuel tanks of Flight 214.[27] Criticism of the JP-4 jet fuel that had been present in the tanks centered around the fact that its vapors can be easily ignited at the low temperatures encountered in flight.[27] JP-4 advocates countered that it was as safe or safer than kerosene, the other fuel used in jets at the time.[27]

Pan American World Airways conducted a flight test in a Boeing 707 to investigate whether fuel could leak from the tank venting system during a test flight that attempted to simulate moderate to rough turbulence in flight. The test did not reveal any fuel discharge, but there was evidence that fuel had entered the vent system, collected in the surge tanks, and returned to the fuel tanks.[1](p9) Pan American said that it would test a new system to inject inert gas into the air spaces above the fuel tanks in aircraft in an attempt to reduce the risk of hazardous fuel-air mixtures that could ignite.[26]

On March 3, 1965, the CAB released the final accident report.[28] The investigators concluded that a lightning strike had ignited the fuel-air mixture in the number 1 reserve fuel tank, which had caused an explosive disintegration of the left outer wing, leading to a loss of control.[1](p1) Despite one of the most intensive research efforts in its history, the agency could not identify the exact mechanics of how the fuel had ignited, concluding that the lightning had ignited vapors through an as-yet unknown pathway.[28] The board said, "It is felt that the current state of the art does not permit an extension of test results to unqualified conclusions of all aspects of natural lightning effects. The need for additional research is recognized and additional programming is planned."[28]

Legacy

The crash of Pan Am Flight 214 called attention to the fact that there were previously unknown risks to aircraft in flight from lightning strikes. One month after the crash, the FAA formed a technical committee on lightning protection for fuel systems, with experts from the FAA, CAB, other government agencies, and lightning experts.[29] The committee made commitments to conduct both long-range and short-range studies of the hazards of lightning on the fuel systems of aircraft, and how to defeat those hazards.[30] In 1967, the FAA updated airworthiness standards for transport category airplanes with requirements that the fuel systems of aircraft must be designed to prevent the ignition of fuel vapor within the system by lightning strikes, and published guidance related to that requirement.[29] Additional requirements to protect the aircraft from lightning were enacted in 1970.[29]

Many aircraft design improvements emerged as a result of the new guidelines and regulations. There was increased attention to the electrical bonding of the components installed in the outer surfaces of the fuel tanks located in the wings, such as fuel filler caps, drain valves, and access panels, to the surrounding structures.[29][28] Fuel vent flame arrestors were added to aircraft to detect and extinguish fuel vapors that had ignited at fuel vent outlets.[19](p36)[29] The thickness of the aluminum surfaces of the wings was thickened in order to reduce the chances that a lightning strike could cause a complete melt-through of the wing surface into the internal components of the wings.[19](p36)[29]

See also

- LANSA Flight 508 – Another accident caused by a lightning strike

- TWA Flight 800 – Aircraft accident caused by ignition of fuel vapors

References

- "Aircraft Accident Report: Pan American World Airways Inc Boeing 707-121, N709PA Near Elkton, Maryland December 8, 1963". Civil Aeronautics Board. March 3, 1965. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- "Pan Am system time table, December 1-31, 1963". University of Miami Digital Collections, Pan American World Airways Records. Pan American World Airways. 1963. p. 15. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- Witkin, Richard (December 10, 1963). "Turbulence Cited in Jetliner Crash". The New York Times. p. 48. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- "Last Words: '...Going Down in Flames'". The Independent. Pasadena, California. Associated Press. December 10, 1963. p. 1. Retrieved May 16, 2019 – via NewspaperArchive.

- "81 on Jet Killed in Flaming Crash Near Elkton, MD". The New York Times. December 9, 1963. p. 1. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on June 12, 2006.

- "Plane Crew Witnessed, Told About Crash of Jet Airliner". Ironwood Daily Globe. Ironwood, Michigan. Associated Press. December 11, 1963. p. 1. Retrieved May 16, 2019 – via NewspaperArchive.

- admin (June 23, 2011). "First Emergency Responder to Arrive on Scene of 1963 Plane Crash Recalls Tragic Night". Window on Cecil County's Past. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- admin (February 17, 2010). "Pan American Airways Crash Worst Disaster in Maryland History". Window on Cecil County's Past. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- Corr, John P.; Janssen, Peter A. (December 9, 1963). "81 Killed as Phila.-Bound Jet Crashes in Storm Near Elkton". Philadelphia Enquirer. p. 1. Retrieved May 27, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- McBride, Dara (December 8, 2013). "50 years later, witnesses, families recall Flight 214 crash". Newark Post. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- "82 Die as Jet Crashes Near Elkton". The Sun. Baltimore, Maryland. December 9, 1963. Retrieved May 27, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Corr, John P.; McAdams, Leonard J. (December 10, 1963). "Key to Crash Mystery Found in Jet Debris". Philadelphia Enquirer. p. 1. Retrieved May 27, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "London May Cover Insurance on Jet". The New York Times. Associated Press. December 10, 1963. p. 48. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- "Jet Airliner Drops Engine in France". The New York Times. UPI. February 26, 1959. p. 62. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- "List of Victims in Crash". The New York Times. Associated Press. December 10, 1963. p. 48. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- "Pilot in Earlier Accident". The New York Times. Associated Press. December 10, 1963. p. 48. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- "2 in Tiny Plane Are Killed As It Rips Clipper in Flight". The New York Times. January 31, 1949. p. 1. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- McClement, Fred (1969). It Doesn't Matter Where You Sit. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. ISBN 0030765102. LCCN 69016187. Retrieved May 8, 2019 – via archive.org.

- Witkin, Richard (December 11, 1963). "U.S. Sees No Need to Restrict Jets". The New York Times. p. 94. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- "CAB Probes Wreckage of Crashed Jet". The Independent. Pasadena, California. Associated Press. December 10, 1963. p. 1. Retrieved May 16, 2019 – via NewspaperArchive.

- "Eyewitnesses Bear Out Supposition That Airliner Was Hit By Lightning". New Castle News. New Castle, Pennsylvania. UPI. February 25, 1964. p. 1. Retrieved May 16, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Witkin, Richard (December 13, 1963). "Bolt of Lightning May Have Hit Jet". The New York Times. p. 51. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- "Lessons Learned from Civil Aviation Accidents: Pan Am Flight 214 at Elkton, Maryland–Accident overview". FAA Lessons Learned. Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- Witkin, Richard (December 18, 1963). "Lightning Danger Stirs Air Experts". The New York Times. p. 59. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- Hudson, Edward (February 27, 1964). "Pan Am To Test Fuel Safeguard". The New York Times. p. 63. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- Hudson, Edward (February 26, 1964). "F.A.A. Will Study Jet Fuel Safety". The New York Times. p. 21. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- "C.A.B. Fails to Fix Cause of a Crash". The New York Times. UPI. March 4, 1965. p. 63. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- "Lessons Learned from Civil Aviation Accidents: Pan Am Flight 214 at Elkton, Maryland–Resulting Safety Initiatives". FAA Lessons Learned. Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- "Program for Investigation of Aircraft Lightning Protection Measures" (PDF). FAA Lessons Learned. Federal Aviation Agency. January 6, 1964. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pan Am Flight 214. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- A Pan American promotional film that features Clipper Tradewind (N709PA)

- A picture of the aircraft involved in the accident (archived from the original on November 4, 2012)

- Another photograph of the aircraft involved