Our Lady of Walsingham

Our Lady of Walsingham is a title of the Blessed Virgin Mary venerated by Catholics and some Anglicans associated with the Marian apparitions to Richeldis de Faverches, a pious English noblewoman, in 1061 in the village of Walsingham in Norfolk, England. Lady Richeldis had a structure built named "The Holy House" in Walsingham which later became a shrine and place of pilgrimage.

| Our Lady of Walsingham | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Walsingham, England |

| Date | 1061 |

| Witness | Richeldis de Faverches |

| Type | Marian apparition |

| Approval | Pope Leo XIII Pope Pius XII |

| Shrine | Basilica of Our Lady of Walsingham Anglican Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham |

| Attributes | The Blessed Virgin Mary enthroned as Queen wearing a golden Saxon crown and golden slippers carrying the Child Jesus with the Gospel book and a Lily flower. |

In passing on his guardianship of the Holy House, Richeldis's son Geoffrey left instructions for the building of a priory in Walsingham. The priory passed into the care of the Canons Regular of St. Augustine, sometime between 1146 and 1174.

Pope Pius XII granted a canonical coronation to the Catholic image via the papal nuncio, Bishop Gerald O'Hara, on 15 August 1954 with a gold crown funded by her female devotees, now venerated in the Basilica of Our Lady of Walsingham.[1]

Marian apparition

According to the tradition, in a Marian apparition to Lady Richeldis, the Blessed Virgin Mary fetched Richeldis’ soul from England to Nazareth during a religious ecstasy to show the house where the Holy Family once lived and in which the Annunciation of Archangel Gabriel occurred. Richeldis was given the task of building a replica house in her village, in England. The building came to be known as the "Holy House", and later became both a shrine and a focus of pilgrimage to Walsingham.

The modern wooden image was carved in Oberammergau, Germany, and was once associated with the Virgin of Mercy under the venerated Marian title of Our Lady of Ransom, sometimes locally worded as "Our Lady of the Dowry". The popularity of the Marian cult gradually localized the place of devotion as "Our Lady of Walsingham".

Holy House and pilgrimages

The historian J. C. Dickinson argues that the chapel was founded in the time of Edward the Confessor, about 1053, the earliest deeds naming Richeldis, the mother of Geoffrey of Favraches, as the founder. Dickinson claims that in 1169, Geoffrey granted "to God and St Mary and to Edwy his clerk the chapel of our Lady" which his mother had founded at Walsingham with the intention that Edwy should found a priory. These gifts were, shortly afterwards, confirmed to the Augustinian Canons of Walsingham by Robert de Brucurt and Roger, earl of Clare.[2]

However, historian Bill Flint (2015) has disputed the foundation date established by Dickinson, arguing that the 1161 Norfolk Roll refers to the foundation of the priory only and not the shrine. Flint supports the earlier date of 1061 given in the Pynson Ballad and claims that in this year, Queen Edith the Fair, Lady of the Manor, was the likely Walsingham visionary.

By the time of its destruction in 1538 during the reign of Henry VIII, the shrine had become one of the greatest religious centres in England and Europe, together with Glastonbury and Canterbury. It had been a place of pilgrimage during medieval times, when due to wars and political upheaval, travel to Rome and Santiago de Compostela was tedious and difficult.[3]

Nevertheless, royal patronage helped the shrine to grow both in wealth and popularity, receiving regal visits from the following kings and queen:

- King Henry III

- King Edward I

- King Edward II

- King Henry IV

- King Edward IV

- King Henry VII

- King Henry VIII

- Queen Catherine of Aragon[4]

Visiting in 1513, Desiderius Erasmus wrote the following:

"When you look in you would say it is the abode of saints, so brilliantly does it shine with gems, gold and silver ... Our Lady stands in the dark at the right side of the altar ... a little image, remarkable neither for its size, material or workmanship."[5]

It was also a place of pilgrimage for Queen Catherine of Aragon who was a regular pilgrim. Likewise, Anne Boleyn also publicly announced an intention of making a pilgrimage but it never occurred. Its wealth and prestige did not, however, prevent its being a disorderly house. The visitation of Bishop Nicke in 1514 revealed that the prior was leading a scandalous life and that, among many other things, he treated the canons with insolence and brutality; the canons themselves frequented taverns and were quarrelsome. The prior, William Lowth, was removed and by 1526 some decent order had been restored.

Destruction

The suppression of the monasteries was part of the English Reformation. On the pretext of discovering any irregularities in their life, Thomas Cromwell organised a series of visitations, the results of which led to the suppression of smaller foundations (which did not include Walsingham) in 1536. Six years earlier the prior, Richard Vowell, had signed their acceptance of the king's supremacy, but it did not save them. Cromwell's actions were politically motivated, but the canons, who had a number of houses in Norfolk, were not noted for their piety or good order.[6] The prior was evidently compliant but not all of the community felt likewise. In 1537, two lay choristers organised "the most serious plot hatched anywhere south of the Trent",[7] intended to resist what they feared, rightly as it turned out, would happen to their foundation. Eleven men were executed as a result. The sub-prior, Nicholas Milcham, was charged with conspiring to rebel against the suppression of the lesser monasteries, and on flimsy evidence was convicted of high treason and hanged outside the priory walls.[4]

The suppression of the Walsingham priory came late in 1538, under the supervision of Sir Roger Townshend, a local landowner. Walsingham was famous and its fall symbolic.

John Hussey wrote to Lord Lisle in 1538: "July 18th: This day our late Lady of Walsingham was brought to Lambhithe (Lambeth) where was both my Lord Chancellor and my Lord Privy Seal, with many virtuous prelates, but there was offered neither oblation nor candle : what shall become of her is not determined." The image is said to have been burned with images from other shrines at some point, publicly, in London. [8] Two chroniclers, Hall and Speed, suggest that the actual burning did not take place until September.

The buildings were looted and largely destroyed, but the memory of it was less easy to eradicate. Sir Roger wrote to Cromwell in 1564 that a woman of nearby Wells (now called Wells-Next-The-Sea) had declared that a miracle had been done by the statue after it had been carried away to London. He had the woman put in the stocks on market day to be abused by the village folk but concluded "I cannot perceyve but the seyd image is not yett out of the sum of ther heddes."[2]

The site of the priory with the churchyard and gardens was granted by the Crown to Thomas Sydney. All that remained of it was the gatehouse, the chancel arch and a few outbuildings. The Elizabethan ballad, "A Lament for Walsingham", expresses something of what the Norfolk people felt at the loss of their shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham.[4]

Pontifical approbations

- Pope Leo XIII issued a Papal decree from Rome blessing the Marian image for public veneration on 6 February 1897.

- Pope Pius XII granted a canonical coronation to the Roman Catholic image via the Papal Nuncio, Bishop Gerald O'Hara, on 15 August 1954 with a gold crown funded by her female devotees, now venerated in the Slipper Chapel.

- Pope John Paul II venerated the image for Pentecost at the Wembley Stadium on 29 May 1982 during an open-air Holy Mass.

- Pope Francis raised her sanctuary to the status of a minor basilica on 27 December 2015 through an apostolic decree from the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments.[9]

Modern revival

.jpg)

After nearly four hundred years the 20th century saw the restoration of pilgrimage to Walsingham as a regular feature of Christian life in the British Isles and beyond. There are both Catholic and Anglican shrines in Walsingham, as well as an Orthodox one.

Slipper Chapel

In 1340, the Slipper Chapel was built at Houghton St Giles, a mile outside Walsingham. This was the final "station" chapel on the way to Walsingham. It was here that pilgrims would remove their shoes to walk the final "Holy Mile" to the shrine barefoot.[5] Hence the designation ‘Slipper’ Chapel.

In 1896, Charlotte Pearson Boyd purchased the 14th-century Slipper Chapel, which had seen centuries of secular use, and set about its restoration.[10] The statue of the Mother and Child was carved at Oberammergau and based on the design of the original statue - a design found on the medieval seal of Walsingham Priory.[5]

In 1897, Pope Leo XIII re-established the restored 14th-century Slipper Chapel as a Catholic shrine, now the centre of the National Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham.[11] The Holy House had been rebuilt at the Church of the Annunciation at King's Lynn (Walsingham was part of this Catholic parish in 1897).

Anglican shrine

The Anglican Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham was created in 1938. In 1921, Fr Hope Patten was appointed Vicar of Walsingham. He set up a statue of Our Lady of Walsingham, based on the image depicted on the seal of the medieval priory, in the Parish Church of St Mary. As the number of pilgrims to the site increased, a new chapel was dedicated in 1931 and the statue was moved to it. The chapel was extended in 1938 to form the current Anglican shrine.[12]

Veneration

There is frequently an ecumenical dimension to pilgrimages to Walsingham, with many pilgrims arriving at the Slipper Chapel and then walking to the Holy House at the Anglican shrine. Student Cross is the longest continuous walking pilgrimage in Britain to Walsingham which takes place over Holy Week and Easter.

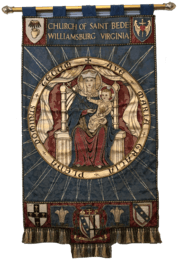

In the United States the National Shrine to Our Lady of Walsingham for the Episcopal Church is located in Grace Church, Sheboygan, Wisconsin, and for the Catholic Church at Saint Bede's Church, Williamsburg, Virginia. Our Lady of Walsingham is remembered by Catholics on 24 September and by Anglicans on 15 October. The personal ordinariate established for former Anglicans in England and Wales is named for of Our Lady of Walsingham. The cathedral of the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of St. Peter in Houston, Texas, is named for Our Lady of Walsingham. The Catholic national shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham is a separate chapel that belongs to the parish of St. Bede's Church in Williamsburg, Virginia.[13] Western Rite Antiochian Orthodox parish named for Our Lady of Walsingham is in Mesquite, Texas. There is a blue Anglican devotional scapular known as the Scapular of Our Lady of Walsingham.

See also

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- A History of the County of Norfolk Vol. 2, William Page VCH pp. 394-401.

- "Welcome message on the Roman Catholic Shrine website". Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 24 April 2008.

- Clayton, Joseph. "Walsingham Priory." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 24 Sept. 2013

- "Brief History of the Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham", Archdiocese of Southwark

- David Knowles Religious Orders in England vol 3 p. 328

- Geoffrey Elton, Policy and Police (Cambridge 1972) p. 144.

- "Our Lady of Walsingham" Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The Tablet, 24 July 1948, p. 8.

- "Pope designates Walsingham shrine as a minor basilica". Catholic Herald. 31 December 2015. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- "Our Lady of Walsingham", The Catholic Community of the University of Nottingham

- "The Catholic National Shrine of our Lady, Walsingham, England". Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- "The Story So Far". walsinghamanglican.org.uk. The Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- Spike, Michèle (2018). The Holy House: A History of the Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham Williamsburg, Virginia. Legion of Mary. p. 40.

Studies

- Dominic Janes and Gary Waller (eds), Walsingham in Literature and Culture from the Middle Ages to Modernity (Aldershot, Ashgate, 2010).

- John Rayne-Davis, Peter Rollings, Walsingham: England’s National Shrine of Our Lady (London, 2010).

- Waller, Gary. Walsingham and the English Imagination. (Aldershot, Ashgate, 2011).

- Bill Flint, "Edith the Fair" (Gracewing, 2015). ISBN 978-0-85244-870-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Our Lady of Walsingham. |

- Anglican National Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham

- Official website of the Anglican and Roman Catholic shrines

- English Roman Catholic National Shrine of Our Lady

- Orthodox church in Walsingham

- US Friends of Our Lady of Walsingham - Episcopal Church

- Icon of Our Lady of Walsingham, St Paul's Church (Episcopal) in Washington, District of Columbia, United States

- Cell of the Holy House of Our Lady of Walsingham, St Thomas the Apostle Church (Episcopal) in Hollywood, California, United States

- Our Lady of Walsingham Orthodox Christian Church in Mesquite, Texas, United States

- Houses of Austin canons: The priory of Walsingham at British History Online

- link to the text of the 15th century Pynson Ballad, recounting the story of the Walsingham shrine

- United States National Catholic Shrine of Our Lady