Ornithocheiridae

Ornithocheiridae is a group of pterosaurs within the suborder Pterodactyloidea. Along with the closely related lonchodectids and targaryendraconians, ornithocheirids were among the last pterosaurs that possess teeth. Members that belong to this group lived from the Early to Late Cretaceous periods (Valanginian to Cenomanian stages), around 140 to 96 million years ago.

| Ornithocheirids | |

|---|---|

| |

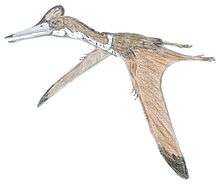

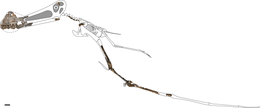

| Restored skeleton of Tropeognathus mesembrinus in the National Museum of Brazil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | †Pterosauria |

| Suborder: | †Pterodactyloidea |

| Clade: | †Lanceodontia |

| Clade: | †Ornithocheirae |

| Clade: | †Anhangueria |

| Family: | †Ornithocheiridae Seeley, 1870 |

| Type species | |

| †Pterodactylus simus Owen, 1861 | |

| Genera | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Ornithocheirids were the most successful pterosaurs during their reign, they were also the largest pterosaurs before the appearance of the azhdarchids such as Quetzalcoatlus. Ornithocheirids were excellent fish hunters, they used various flight techniques to catch their prey, and they are also capable of flying great distances without flapping constantly. The later existence of the crested pteranodontids made paleontologists think that ornithocheirids were their potential ancestors. This is due to their very similar aspects such as the different flying techniques, the long distance flights, and most of all their diet, which consists mainly on fish.[1][2]

History of research

Earliest finds

Fossil remains from the Chalk Formation in Burham near Kent, England were uncovered by British paleontologist James Scott Bowerbank in 1851.[3] He assigned these specimens to a new species called Pterodactylus cuvieri, as Pterodactylus was the best known genus of pterosaur at that time, and therefore assigning new species to it was practical.[3] The specific name is honoring Georges Cuvier, the noted French naturalist and zoologist of the 19th century. A few years later, British paleontologist Richard Owen also uncovered pterosaur remains in the same chalk pit of the Chalk Formation, he assigned these recovered specimens to a new species, which he named Pterodactylus compressirostris, but the remains differed from P. cuvieri for having a more elongated snout.[4][5] This species was later classified to the genus Lonchodectes in a review by paleontologist Reginald Walter Hooley in 1914.[6]

In 1861, Richard Owen had described several new specimens unearthed from the same formation where P. cuvieri was discovered. These remains also looked very similar to it in its overall anatomy, and therefore Owen assigned the remains to Pterodactylus simus.[7] In 1869 however, British paleontologist Harry Govier Seeley erected a new genus called Ornithocheirus (from Ancient Greek meaning "bird hand"), as many researchers at the time still considered pterosaurs as direct ancestors of birds.[7] Seeley also renamed Pterodactylus cuvieri into Ptenodactylus cuvieri.[8] However, in 1870, he found out that the generic name Ptenodactylus had been considered a nomen nudum, and therefore he reassigned P. cuvieri to the new genus Ornithocheirus, creating Ornithocheirus cuvieri.[9] Later that year, Seeley reassigned various species of pterosaurs that had been named at the time to Ornithocheirus, but he did not designate a type species for the genus. He also published his conclusions in a book called The Ornithosauria, which mainly consisted of his thoughts and conclusions about pterosaurs. The name of the book translates to "bird lizard", in reference of pterosaurs being the direct ancestors of birds.[10]

Controversy of Ornithocheirus

Finding out that Seeley had assigned at least 27 species of pterosaur to Ornithocheirus, and even publishing a book about his conclusions had made Owen consider the name Ornithocheirus invalid, or at the very least inappropriate.[5] In 1874, Owen had created two new genera: Coloborhynchus (meaning "maimed beak") and Criorhynchus (meaning "ram beak"), in reference to their unique snout. Owen also created a type species for Coloborhynchus, C. clavirostris, and reassigned Ornithocheirus simus as the type species of Criorhynchus, making a Criorhynchus simus. Along with the type species, Owen also reassigned 2 former species of Ornithocheirus to Coloborhynchus, and 5 former species to Criorhynchus. In the same year, he reassigned Pterodactylus cuvieri into Coloborhynchus, making a Coloborhynchus cuvieri.[5][9]

Seeley disagreed with Owen's position, and he therefore assigned O. simus as the type species of Ornithocheirus, and also created a new separate species called O. bunzeli. In 1888, the paleontologist Edwin Tulley Newton reassigned several existing species of Coloborhynchus into Ornithocheirus, including C. clavirostris, the type species.[11][12]

In a 1914 study, the paleontologist Reginald Hooley kept the name Ornithocheirus, but created two new genera: Lonchodectes (meaning "lance biter"), and Amblydectes (meaning "blunt biter"). This classification was rarely applied at that time, and therefore some paleontologists weren't aware.[6] The species Pterodactylus compressirostris became the type species of Lonchodectes in Hooley's 1914 review of Ornithocheirus, which was originally a species of it according to Seeley back in 1870.[10] Confusingly, P. compressirostris was long regarded, incorrectly, as the type species of Ornithocheirus.[6]

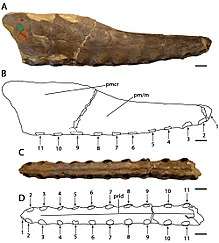

In 2013, further studies on the genus Ornithocheirus were made, as well as on the species Pterodactylus cuvieri, a long regarded species of Ornithocheirus, known as O. cuvieri. The Brazilian paleontologists Taissa Rodrigues & Alexander Kellner however, analyzed the specimens of P. cuvieri, which was named as "O." cuvieri in the analysis, and concluded that it differed from Ornithocheirus due to a series of autapomorphies. Some of which included its crest being placed far back on the premaxilla, at the level of the seventh tooth pair, but begins before the large skull opening; there is a density of three teeth per 3 centimeters (1.2 in) at the front of the upper jaw and of two teeth at the back of the jaw. These distinguishing traits made it unique, and therefore Rodrigues & Kellner erected a new genus called Cimoliopterus, and created the new combination Cimoliopterus cuvieri. The generic name combines Κιμωλία, Kimolia (meaning "chalk" in New Greek) , in reference to the white clay of the island Kimolos, and the Latinised Greek word πτερόν, pteron (meaning "wing").[9]

South American discoveries

In 1987, fossil remains from the Santana Group (sometimes called the Santana Formation) in Brazil were thought to belong to Ornithocheirus, the paleontologist Peter Wellnhofer described the newly uncovered specimens, and made a new genus called Tropeognathus (meaning "keel jaw"), in reference to it being similar a keel. Wellnhofer also assigned a type species named T. mesembrinus.[13] These remains were specifically discovered in the Romualdo Formation of the Santana Group, alongside another similar pterosaur called Anhanguera.[14] The newly named Tropeognathus mesembrinus by Wellnhofer led to an enormous taxonomic confusion by certain paleontologists, this is due to the similarities it had with Anhanguera. During the year 1989, the species was considered an Anhanguera mesembrinus by Brazilian paleontologist Alexander Kellner,[15] then a Criorhynchus mesembrinus in 1998 by André Jacques Veldmeijer,[16] and a Coloborhynchus mesembrinus was erected in 2001 by Michael Fastnacht.[17][9] Paleontologist David Unwin however, considered T. mesembrinus a junior synonym of Ornithocheirus simus, though he then proposed an Ornithocheirus mesembrinus in 2003.[1] In 2013 however, Taissa Rodrigues and Alexander Kellner concluded that Tropeognathus would be valid again, and containing only T. mesembrinus, its type species.[9]

Anhanguera, meaning "bygone spirit protector of the animals", sometimes simplified as "old devil", is also a well known relative of the ornithocheirids, and its remains were found in the same formation as Tropeognathus, its fossils date back to the Albian stage of the Early Cretaceous, around 112 million years ago.[14] Because of its similarity to Ornithocheirus and Tropeognathus, authors assigned several species to it, including O. cuvieri into Anhanguera cuvieri by David Unwin in 2001, and the already mentioned Anhanguera mesembrinus by Alexander Kellner in 1989.[18]

Another pterosaur discovered in the Santana Group is Santanadactylus, it was described by Wellnhofer in the same year as Anhanguera, and a specific species of it was assigned to Anhanguera, S. araripensis, which in the description was reassigned as Anhanguera araripensis.[19] Santanadactylus is also similar to Ornithocheirus, however, it is recently considered a basal pteranodontoid due to placement uncertainties.[20]

Other discoveries

The genus Uktenadactylus from the Paw Paw Formation in Texas is a curious discovery, a partial snout was the only thing unearthed, and it was originally named Coloborhynchus wadleighi by Yuong Nam-Lee. He assigned this new species to Coloborhynchus because they share the trait of having three pairs of teeth laterally placed within a broad snout tip. The fossil that was found has a length of about 15 centimeters (5.9 in) and consists of the front end of the skull, containing the premaxilla and a small part of the maxilla.[21] In 2009 however, Rodrigues & Kellner erected a new genus for the species: Uktenadactylus (meaning "Uktena finger"), in reference to the giant horned snake from the mythology of the Cherokee. Rodrigues & Kellner base upon a possible age difference of perhaps over thirty million years between the Berriasian-Valanginian British and the younger Albian-Cenomanian American form, and therefore C. wadleighi was potentially different from Coloborhynchus. The age difference basis is because of the more derived and advanced features seen in C. wadleighi, as well as different from those of C. clavirostris.[22] Now named as Uktenadactylus, paleontologists have analyzed it deeper, and found out that many traits were shared with other ornithocheirids, but mostly similar to those of Coloborhynchus, and thus placed within the Coloborhynchinae, a subfamily consisting of genera closer related to Coloborhynchus rather than Ornithocheirus.[23]

Fossil remains uncovered from the Toolebuc and Winton formations in Australia are now thoght to belong to potential ornithocheirids. These specimens were overall similar to Ornithocheirus, one of which consisted only of the middle snout and parts of the mandible. This genus unearthed from the Toolebuc Formation was named Mythunga, in reference to the Orion constellation in the local aboriginal language.[24] The other genus was named as Ferrodraco (meaning "iron dragon"), in reference to the fact that the skeleton was found in ironstone. Its remains were discovered in 2019, and consisted on a partial skeleton, a skull and the lower jaws. These two genera were very similar to Ornithocheirus, and therefore placed within the subfamily Ornithocheirinae.[25][26]

Description

Size

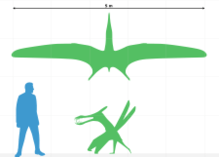

Ornithocheirids were among the largest pterosaurs that ever flew the skies, and perhaps even comparable to the sizes of the largest azhdarchids.[27] Wingspan estimates ranged from 4 to 7 meters (13 to 23 ft), though most were typically around 5 meters (16 ft).[28][29] The ornithocheirids Ornithocheirus and Coloborhynchus likely measured around 4.5 to 6.1 meters (15 to 20 ft), with some estimates exceeding 7 metres (23 ft), this made them quite large for their time, but the diverse evolution of ornithocheirids in the Early Cretaceous had made paleontologists understand that they were likely the most typical species of pterosaur during their reign. The largest size for an ornithocheirid was recorded in 2013 by the Kellner et al., which uncovered and described unusually large specimens of the ornithocheirid Tropeognathus.[28] These specimens consisted of a skeleton with skull, and extensive elements of all body parts except the tail and the lower hindlimbs, this then led to an impressive wingspan estimate measuring 8.2 meters (27 ft).[30][9]

Other smaller genera include the crested Caulkicephalus, meaning "caulk head", in reference of the Isle of Wight.[31] The newly named Ferrodraco from the Winton Formation in Australia is also one of the smaller ornithocheirines, though still large compared to the other ornithocheirids.[26] Caulkicephalus is estimated with a wingspan of around 5 meters (16 ft), making it average within ornithocheirid wingspan size. The wingspan of Ferrodraco however, measured at least 4 meters (13 ft), which is slightly shorter, making it slightly smaller than Caulkicephalus.[31][26]

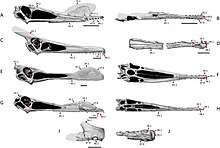

Skull and crests

Most ornithocheirids are known for their prominent "keeled" crest over, and under their snout, which is more precisely on the premaxilla, and the underside of the mandible. This trait made ornithocheirids unique pterosaurs. Ornithocheirus for example, had very similar jaws to Coloborhynchus, but can be differed by its much narrower structure, Tropeognathus on the other hand, had a larger premaxilla, but its snout isn't nearly as narrow.[9][22] The "keeled" crest on Tropeognathus was also well-developed and more prominent than in Ornithocheirus, an indication that it was respectively larger in size.[32][33]

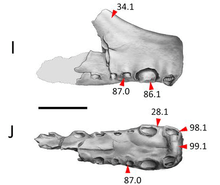

The ornithocheirid Coloborhynchus also shares features with Anhanguera, leading to a confusing classification with Ornithocheirus within Anhangueridae and Ornithocheiridae. The tip of the snout in Coloborhynchus flared out into a wider rosette, in contrast to its narrow posterior premaxilla.[22] These features differed it from Anhanguera, which has a rounded and spoon-shaped snout in comparison to the robust and box-shaped snout of Coloborhynchus. This led to the idea that Coloborhynchus was closer related to Ornithocheirus rather than Anhanguera, but then again, it had unique features such as the position of its tooth sockets and its jawtip being less curved. The keel-shaped crest on the premaxilla in Coloborhynchus was also thinner than in close relatives such as Tropeognathus. Another conclusion was that Coloborhynchus was most likely placed in its own subfamily, the Coloborhynchinae, but still within Ornithocheiridae.[22][34]

One of the more specialized ornithocheirids is Caulkicephalus, it didn't only had the convex "keeled" crests on its snout and underside of the mandible, but it also had the similar sagittal crest that the later pteranodontids had. This is led to an idea of how pteranodontids evolved or acquired their sagittal crest from their ornithocheirid cousins, but fossil remains of Caulkicephalus are scarce, so extracting accurate evolutionary data is difficult.[31]

The recently named Ferrodraco also shares several features with Ornithocheirus and Tropeognathus, and therefore was placed in this family. Ferrodraco possesses an elongated snout with a "keeled" crest similar to that of Ornithocheirus, but its premaxilla has a triangular shape and it's likely more flattened compared to other ornithocheirids.[9][26] The first tooth pair in the premaxillae is also directed vertically and is slightly set-off from above the jawline. These autapomorphies are unique in Ferrodraco, and are probably related to its more advanced evolutionary changes.[26]

Wings

According to many studies, the wing-membranes of the ornithocheirids were extensive and broad, resulting in a high aspect ratio, analyses also show that most ornithocheirids had low wing loadings, which led to an easier maneuver during flight.[35] Most wing-membranes of ornithocheirids also had pycnofibres, hair-like filaments that were unique in structure, but not homologous with mammalian hair, an example of convergent evolution. Ornithocheirid wings mostly differed from the earlier istiodactylid wings because of their impressive size, and the wings weren't only capable of soaring high, but also soaring very long distances without flapping.[36]

Pelvic structure

Studies of the pelvis of several ornithocheirids show that they were mostly of moderate size compared to the body as a whole, which is similar to the structures in other ornithocheiroids. The pelvic bones, which in total were three, were fused, this is seen in many genera such as Anhanguera. The ilium was long and low, and its front and rear blades projected horizontally beyond the edges of the lower pelvic bones.[37] Given the structure length, the processes of these rod-like forms indicate that the hindlimb muscles attached to them with limited strength.[30] An ischiopubic blade is seen in most ornithocheirids, where the pubic bone is fused with the broad ischium, resulting in a narrow build.[38] The front of the pubic bones were also articulated with a unique structure, resulting in a pair of prepubic bones within, this formed a cusp covering the rear belly of the pterosaur, and was located between the pelvis and the belly ribs. This element suggests of a vertical mobility, and therefore had a function in breathing, with the chest cavity compensating in a relative rigidity.[39] Normally, the blades of ornithocheirids, most notably in the larger genera, were fused in both sides, closing the pelvis from below and forming the pelvic canal. Ornithocheirids didn't have the hip joint perforated, but directed obliquely upwards, preventing a perfectly vertical position of the leg, and therefore allowed considerable mobility for the hindlimbs.[40][38]

Vertebrae

Vertebral columns and vertebrae of ornithocheirids are only known from scarce remains, and it is hard to determine how their posture were. In some genera such as Tropeognathus, the first five dorsal vertebrae are fused into a notarium, with five sacral vertebrae fused into a synsacrum, and the third and fourth sacral vertebrae are keeled within. Ornithocheirids also had a relatively long and straight neck. The more advanced species typically had their neck longer than their torso.[38]

Classification

Evolution

Ornithocheirids were impressively large compared to other types of pterosaurs from the Early Cretaceous, and they were also one of the most successful of all pterosaurs.[41][42] Some paleontologists suggested that the closely related Istiodactylus was an ancestor of the later ornithocheirids, and probably shared common features such as their diet.[43] The conclusion of Istiodactylus preying on fish however, was considered inappropriate, as its skull was said to be thicker and more compact, and some of the remains were also misplaced, leading to a misunderstanding of a duck-like beak.[44][45] Most ornithocheirids were long considered to only have a piscivorous diet, while this is mostly true, some remains uncovered were suggested to belong to an ornithocheirid with a non-piscivorous diet.[2]

Other evolutionary changes of ornithocheirids include their territorial range, they were even present in the southern continent of Oceania, represented by two genera: Ferrodraco and Mythunga.[26][25] Most of the species discovered in Europe and South America belonged to Coloborhynchus and Ornithocheirus, with some currently being synonyms of Tropeognathus and Anhanguera.[22][32]

A lot of paleontologists also consider the pteranodontids such as Pteranodon and Geosternbergia as the later evolutions of the ornithocheirids, this is due to their very similar hunting aspects as well as their long-distance flights. Ornithocheirids such as Tropeognathus also had a very high aspect ratio, which is also seen in Pteranodon.[46] Other features seen through the evolutionary changes are the teeth, which were present in the ornithocheirids, but absent in the later pteranodontids, this can also be an indication that genera from this family are likely the direct ancestors of the later pterosaur species.[1][29][47] They are notable for their high, conical tooth sockets and raised alveolar margins.[48]

Phylogeny

The family Ornithocheiridae is mostly placed as the most derived family in the cladograms of various phylogenetic analyses, but contrary to this classification, the most derived clades are found to have been the family Lonchodectidae and the newly named clade Targaryendraconia, with specimens dating back to the Cenomanian stage of the Late Cretaceous, around 94 million years ago.[49][1]

The genus Cimoliopterus, originally Pterodactylus cuvieri, and once assigned to Ornithocheirus as O. cuvieri, was reclassified as a targaryendraconian in 2019. Paleontologists found it to be closer to the newly named Targaryendraco (originally Ornithocheirus wiedenrothi), but as the sister taxon of Aetodactylus and Camposipterus within the group.[9][49]

Autapomorphies found unique in Coloborhynchus made authors assign it to the new subfamily Coloborhynchinae. However, some authors placed Coloborhynchus within the family Anhangueridae instead,[23] and with the later discovery of Uktenadactylus, which shared very similar features with coloborhynchines, it was suggested that it would be the sister taxon of Coloborhynchus.[22] The phylogenetic placement of Ornithocheiridae was conducted by Andres and Myers in 2013, where they placed the family as the sister taxon of Anhangueridae, and within the more inclusive group Ornithocheirae.[50] A later analysis by Pentland et al. in 2019 had created the subfamily Ornithocheirinae, with the genera Ferrodraco, Mythunga, Ornithocheirus, and interestingly Coloborhynchus as the members. In the analysis, they also placed the genus Tropeognathus within the family, but in a basal position.[26]

|

Topology 1: Andres & Myers (2013).[50]

|

Topology 2: Pentland et al. (2019).[26]

|

Paleobiology

Feeding and diet

Unlike the related istiodactylids, ornithocheirids were mainly fish hunters, consisting on a piscivorous diet that varied depending on the species. Paleontologists suggest that the feeding habits of the earlier istiodactylids changed through the process of evolution, resulting in a more aquatic-based lifestyle. The studies and analyzes of the ornithocheirids Tropeognathus and Ornithocheirus made paleontologists conclude how they hunted or catched fish successfully.[13] The first basis is their long snouts, which they used for catching the fish near the surface of the water, paleontologists also suggest that they flew with moderated speed, giving them an overall advantage of a surprise attack during the hunt. Others suggest that ornithocheirids, similar to pteranodontids, just glided down directly to the water when catching prey, this technique can also be seen in modern-day soaring birds such as albatrosses.[51] Pteranodontids use another flying technique called "dynamic soaring", which is also seen in albatrosses, and some paleontologists erect the idea that ornithocheirids did the same.[1][52]

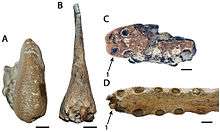

Teeth enamels

Some discoveries, found that several ornithocheirids weren't completely fish hunters or aquatic consumers. This is confirmed with a 2017 analysis of carbon isotopes found on teeth enamels of ornithocheirids. In the analysis, they compared the enamel values of ornithocheirids with the aquatic and terrestrial consumers near the fossil site.[2] The ornithocheirid enamels found in the Twin Mountains Formation were shown with lower enamel values compared to the aquatic consumers that lived nearby, suggesting a more terrestrial diet, similar to the carnivorous theropods found in the site, such as Acrocanthosaurus. Enamels found in the Paw Paw Formation however, were described with higher values, in comparison to the nearby terrestrial consumers. These enamel remains were analyzed, and paleontologists then found out that the values seen were more similar to aquatic consumer enamels rather the terrestrial ones.[2] These analyses are considered very useful reference, since there isn't much data on several ornithocheirid genera. The earlier species that partially fed on terrestrial prey, such as Coloborhynchus, were also analyzed, and paleontologists conclude that there can be a specific evolutionary change between the earlier and later formations, due to the age difference.[22] This can be demostrated with the enamel remains found in the Twin Mountains and Paw Paw formations. The ones found in the Twin Mountains Formation dated back to the earlier Aptian stage, while the remains found in the Paw Paw Formation dated back to the later Albian stage.[2]

Locomotion and flight

Similar to modern-day albatrosses, most ornithocheirids used a flight technique called "dynamic soaring", which consists of travelling long distances without flapping using the vertical gradient of wind speed near the ocean surface as an advantage, but the flight speed is moderate. Several footprints from some species were also found, and shows that most pterosaurs didn't sprawl their limbs to a large degree, as in modern reptiles, but rather held their limbs relatively erect when walking, like the distant related dinosaurs.[36] Some studies in the later genera, show that ornithocheirids spend lots of their time sea fishing, and as a result, they perhaps influenced the later pteranodontids with the same piscivorous diet, as well as their well developed flight techniques.[53][54] Analyses of limb proportions in the genus Anhanguera however, show that some ornithocheirids were consistent on hopping, but the later genera were suggested that they most likely walked on four limbs, which consists on their wing-fingers as the front limbs, and using their hind limbs to balance.[55][56]

Paleoecology

Ornithocheirids were a widespreaded type of pterosaurs, with many fossil remains found across the world. The first true ornithocheirid specimens were uncovered in the Cambridge Greensand of England, these belong to the infamous genus Ornithocheirus, and dated back to the Albian stage of the Early Cretaceous.[57] Within the fossil site, several other pterosaurs were also found, these include the ornithocheirids Amblydectes and Coloborhynchus,[22] the targaryendraconian Camposipterus, the lonchodectid Lonchodraco,[9] and the azhdarchoid Ornithostoma.[58] The ornithischians Anoplosaurus, Acanthopholis,[59] and the dubious Eucercosaurus and Trachodon were also found within the formation.[60] Fossil remains of the sauropod Macrurosaurus were also present.[61] The bird Enaliornis,[62] as well as the ichthyosaurs Cetarthrosaurus, Platypterygius and Sisteronia were also found alongside the remains of ornithocheirids.[63]

A Lagerstätte called the Santana Group (sometimes known as the Santana Formation) in northeastern Brazil was found to contain a large number of pterosaur genera. The most diverse formation of the group is the Romualdo Formation, known for its wide variety of pterosaur remains.[33] The formation dates back 111 to 108 million years ago, during the Albian stage of the Early Cretaceous, which is similar to the Cambridge Greensand. The Romualdo Formation is found to contain a variety of ornithocheirids, including Tropeognathus,[28] Coloborhynchus[22] and Araripesaurus,[64] the targaryendraconian Barbosania,[65] and the anhanguerids Anhanguera and Maaradactylus were also found alongside.[66] The related Araripedactylus, Brasileodactylus,[67] Cearadactylus,[68] Santanadactylus[20] and Unwindia[69] were also present within the fossil site. Many other pterosaur were found within, these include the tapejarid Tapejara,[70] as well as the thalassodromids Thalassodromeus[71] and Tupuxuara.[72] Other animals such the theropods Irritator,[73] Mirischia[74] and Santanaraptor, as well as the crocodylomorph Araripesuchus were also found.[75] Several turtle remains were found within the formation, with some specimens referring to the genera Santanachelys, Cearachelys and Araripemys,[76][77] and along with these, many fish remains were also found, these were assigned to the genera Brannerion, Rhinobatos, Rhacolepis, Tharrhias and Tribodus.[78]

Ornithocheirids were also partially distributed in North America, and several specimens that were found are thought to belong to the genus Uktenadactylus (originally Coloborhychus wadleighi).[21] This pterosaur was uncovered in the Paw Paw Formation of Texas, USA, which dated back to the Albian and Cenomanian stages. The formation includes several ankylosaurian dinosaurs such as Pawpawsaurus, Texasetes, and an indetermine nodosaurid.[79][80][81] Within the fossil site, several specimens of ammonoids were thought to belong to the genera Turrilites and Scaphites,[82] and along with these, shark remains of Leptostyrax were also found.[83]

See also

References

- Unwin, D. M. (2003). "On the phylogeny and evolutionary history of pterosaurs". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 217 (1): 139–190. Bibcode:2003GSLSP.217..139U. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.924.5957. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2003.217.01.11.

- "Abstract: DIET OF ORNITHOCHEIROID PTEROSAURS INFERRED FROM STABLE CARBON ISOTOPE ANALYSIS OF TOOTH ENAMEL (GSA Annual Meeting in Seattle, Washington, USA - 2017)". gsa.confex.com.

- Bowerbank, J.S. (1851). "On the pterodactyles of the Chalk Formation". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 19: 14–20. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1851.tb01125.x.

- Owen, R. (1851). Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Cretaceous Formations. The Palaeontographical Society 5(11):1-118. doi:10.1080/02693445.1851.12088366

- Owen, R. (1874). Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Mesozoic Formations. 1. Palaeontographical Society. p. 14.

- Hooley, Reginald Walter (1914). "On the Ornithosaurian genus Ornithocheirus, with a review of the specimens from the Cambridge Greensand in the Sedgwick Museum, Cambridge". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 13 (78): 529–557. doi:10.1080/00222931408693521. ISSN 0374-5481.

- Martill, D.M. (2010). "The early history of pterosaur discovery in Great Britain". Geological Society of London, Special Publications. 343 (1): 287–311.

- Seeley, H.G., 1869, Index to the fossil remains of Aves, Ornithosauria, and Reptilia, from the Secondary System of Strata, arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge. St. John's College, Cambridge 8: 143. doi:10.1080/00222937008696143

- Rodrigues, T.; Kellner, A. (2013). "Taxonomic review of the Ornithocheirus complex (Pterosauria) from the Cretaceous of England". ZooKeys (308): 1–112. doi:10.3897/zookeys.308.5559. PMC 3689139. PMID 23794925.

- Seeley, H.G. (1870). The Ornithosauria: an Elementary Study of the Bones of Pterodactyles. Cambridge. p. 113.

- Seeley, H. G. (1881). "The Reptile Fauna of the Gosau Formation preserved in the Geological Museum of the University of Vienna". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 37 (1): 620–706. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1881.037.01-04.49.

- Newton, E. T., 1888, "On the Skull, Brain, and Auditory Organ of a new species of Pterosaurian (Scaphognathus purdoni), from the Upper Lias near Whitby, Yorkshire", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, v. 179, p. 503-537

- Peter Wellnhofer, 1987, "New crested pterosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil", Mitteilungen der Bayerischen Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und historische Geologie 27: 175–186; Muenchen

- Campos, D. de A., and Kellner, A. W. (1985). "Um novo exemplar de Anhanguera blittersdorffi (Reptilia, Pterosauria) da formação Santana, Cretaceo Inferior do Nordeste do Brasil." In Congresso Brasileiro de Paleontologia, Rio de Janeiro, Resumos, p. 13.

- Kellner, A.W.A. (1989). "A new Edentate Pterosaur of the lower Cretaceous from the Araripe Basin, Northeast Brazil". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias. 61: 439–446.

- Veldmeijer, A.J. "Pterosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil in the Stuttgart Collection". Geoscience and Engineering. 327: 1–27.

- Fastnacht, M (2001). "First record of Coloborhynchus (Pterosauria) from the Santana Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of the Chapada do Araripe of Brazil". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 75: 23–36. doi:10.1007/bf03022595.

- Unwin, D.M., 2001, "An overview of the pterosaur assemblage from the Cambridge Greensand (Cretaceous) of Eastern England", Mitteilungen aus dem Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, Geowissenschaftliche Reihe 4: 189–221

- Wellnhofer, P. (1985). Neue Pterosaurier aus der Santana-Formation (Apt) der Chapada do Araripe, Brasilien. Paläontographica A 187:105-182. [German]

- P. H. Buisonjé. 1980. Santanadactylus brasilensis nov. gen., nov. sp., a long-necked, large pterosaurier from the Aptian of Brasil. Proceedings of the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, B 83:145-172

- Lee, Y.-N. (1994). "The Early Cretaceous Pterodactyloid Pterosaur Coloborhynchus wadleighi from North America". Palaeontology. 37 (4): 755–763.

- Rodrigues, T. and Kellner, A.W.A. (2008). "Review of the pterodactyloid pterosaur Coloborhynchus". Flugsaurier: pterosaur papers in honour of Peter Wellnhofer. Zitteliana B. 28: 219–228.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Kellner, Alexander W. A.; Caldwell, Michael W.; Holgado, Borja; Vecchia, Fabio M. Dalla; Nohra, Roy; Sayão, Juliana M.; Currie, Philip J. (2019). "First complete pterosaur from the Afro-Arabian continent: insight into pterodactyloid diversity". Scientific Reports. 9 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-019-54042-z.

- Molnar, Ralph E.; Thulborn, R.A. (2008). "An incomplete pterosaur skull from the Cretaceous of north-central Queensland, Australia". Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro. 65 (4): 461–470.

- Adele H. Pentland; Stephen F. Poropat, 2018, "Reappraisal of Mythunga camara Molnar & Thulborn, 2007 (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea, Anhangueria) from the upper Albian Toolebuc Formation of Queensland, Australia". Cretaceous Research doi: 10.1016/j.cretres.2018.09.011

- Pentland, Adele H.; Poropat, Stephen F.; Tischler, Travis R.; Sloan, Trish; Elliott, Robert A.; Elliott, Harry A.; Elliott, Judy A.; Elliott, David A. (December 2019). "Ferrodraco lentoni gen. et sp. nov., a new ornithocheirid pterosaur from the Winton Formation (Cenomanian–lower Turonian) of Queensland, Australia". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 13454. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49789-4. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6776501. PMID 31582757.

- Witton 2013, p. 249.

- Kellner, A. W. A.; Campos, D. A.; Sayão, J. M.; Saraiva, A. N. A. F.; Rodrigues, T.; Oliveira, G.; Cruz, L. A.; Costa, F. R.; Silva, H. P.; Ferreira, J. S. (2013). "The largest flying reptile from Gondwana: A new specimen of Tropeognathus cf. T. Mesembrinus Wellnhofer, 1987 (Pterodactyloidea, Anhangueridae) and other large pterosaurs from the Romualdo Formation, Lower Cretaceous, Brazil". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 85: 113–135. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652013000100009. PMID 23538956.

- Kellner, A. W. A. (2003). "Pterosaur phylogeny and comments on the evolutionary history of the group". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 217 (1): 105–137. Bibcode:2003GSLSP.217..105K. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2003.217.01.10.

- Witton 2013, p. 162.

- Steel, L., Martill, D.M., Unwin, D.M. and Winch, J. D. (2005). "A new pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Wessex Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of the Isle of Wight, England". Cretaceous Research. 26: 686–698. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2005.03.005.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Veldmeijer, A.J. 2002, "Pterosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil in the Stuttgart collection", Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde Serie B (Geologie und Paläontologie) 327: 1–27

- Veldmeijer, A.J. (2006). "Toothed pterosaurs from the Santana Formation (Cretaceous; Aptian-Albian) of northeastern Brazil. A reappraisal on the basis of newly described material Archived 2012-03-17 at the Wayback Machine." Tekst. - Proefschrift Universiteit Utrecht.

- Martill, David M. (2015), First occurrence of the pterosaur Coloborhynchus (Pterosauria, Ornithocheiridae) from the Wessex Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of the Isle of Wight, England., 126, 3, Proceedings of the Geologists' Association, pp. 377–380, archived from the original on 2016-10-26, retrieved 2016-10-26

- Witton 2013, pp. 158-159.

- Padian, K. (1983). "A functional analysis of flying and walking in pterosaurs". Paleobiology. 9 (3): 218–239. doi:10.1017/S009483730000765X.

- Wellnhofer 1991, p. 55.

- Witton 2013, p. 159.

- Witton 2013, p. 163.

- Witton 2013, p. 179.

- Witton 2013, pp. 153-154.

- Martill, D.M. and Unwin, D.M. (2011). "The world's largest toothed pterosaur, NHMUK R481, an incomplete rostrum of Coloborhynchus capito (Seeley 1870) from the Cambridge Greensand of England." Cretaceous Research, (advance online publication). doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2011.09.003

- Witton, M. P. (2012). "New Insights into the Skull of Istiodactylus latidens (Ornithocheiroidea, Pterodactyloidea)". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e33170. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...733170W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033170. PMC 3310040. PMID 22470442.

- Witton 2013, p. 143.

- Howse, S. C. B.; Milner, A. R.; Martill, D. M. (2001). "Pterosaurs". In Martill, D. M.; Naish, D. (eds.). Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight. Guide 10; Field Guides to Fossils. London: The Palaeontological Association. pp. 324–335. ISBN 978-0-901702-72-2.

- Martin-Silverstone, E., Glasier, J., Acorn, J., Mohr, S., and Currie, P. 2017. Reassesment of Dawndraco kanzai Kellner, 2010 and reassignment of the type specimen to Pteranodon sternbergi Harksen, 1966. Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology, 3:47-59. doi:10.18435/B5059J

- Averianov, A.O. (2020). "Taxonomy of the Lonchodectidae (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea)". Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS. 324 (1): 41–55. doi:10.31610/trudyzin/2020.324.1.41.

- Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy, Mark P. Witton (2013)

- Rodrigo V. Pêgas, Borja Holgado & Maria Eduarda C. Leal (2019) On Targaryendraco wiedenrothi gen. nov. (Pterodactyloidea, Pteranodontoidea, Lanceodontia) and recognition of a new cosmopolitan lineage of Cretaceous toothed pterodactyloids, Historical Biology, doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1690482

- Andres, B.; Myers, T. S. (2013). "Lone Star Pterosaurs". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 103 (3–4): 1. doi:10.1017/S1755691013000303.

- Bennett, S.C. (1994). "Taxonomy and systematics of the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Pteranodon (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea)" (PDF). Occasional Papers of the Natural History Museum, University of Kansas. 169: 1–70.

- Kellner, A.W.A. (2010). "Comments on the Pteranodontidae (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) with the description of two new species" (PDF). Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 82 (4): 1063–1084. doi:10.1590/S0001-37652010000400025. PMID 21152777.

- Witton 2013, pp. 161-162.

- Witton, M.P.; Habib, M.B. (2010). "On the Size and Flight Diversity of Giant Pterosaurs, the Use of Birds as Pterosaur Analogues and Comments on Pterosaur Flightlessness". PLOS ONE. 5 (11): e13982. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...513982W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013982. PMC 2981443. PMID 21085624.

- Habib, M. (2011). "Dinosaur Revolution: Anhanguera." H2VP: Paleobiomechanics. Weblog entry, 20-SEP-2011. Accessed 28-SEP-2011: http://h2vp.blogspot.com/2011/09/dinosaur-revolution-anhanguera.html

- Hooley, R. W. (1913). "On the skeleton of Ornithodesmus latidens; an ornithosaur from the Wealden Shales of Atherfield (Isle of Wight)". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 69 (1–4): 372–422. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1913.069.01-04.23.

- Haines, T., 1999, "Walking with Dinosaurs": A Natural History, BBC Books, p. 158

- Averianov A.O. (2012). "Ornithostoma sedgwicki – valid taxon of azhdarchoid pterosaurs". Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS. 316 (1): 40–49.

- Nopcsa, Baron Francis (1923). "Notes on the British dinosaurs, Part IV: Acanthopholis". Geological Magazine. 60 (5): 193–199. doi:10.1017/S0016756800085563.

- Seeley, H. G. (1879). "On the Dinosauria of the Cambridge Greensand". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 35 (1–4): 591–635. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1879.035.01-04.42.

- H.G. Seeley, 1876, "On Macrurosaurus semnus (Seeley), a long tailed animal with procoelous vertebrae from the Cambridge Upper Greensand, preserved in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge", Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 32: 440-444 doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1876.032.01-04.50

- Harrison, C.J.O.; Walker, C.A. (1973). "Wyleyia: a new bird humerus from the Lower Cretaceous of England" (PDF). Palaeontology. 16 (4): 721–728. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-06.

- Valentin Fischer; Nathalie Bardet; Myette Guiomar & Pascal Godefroit (2014). "High Diversity in Cretaceous Ichthyosaurs from Europe Prior to Their Extinction". PLoS ONE. 9 (1): e84709. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084709. PMC 3897400. PMID 24465427.

- Dalla, F.V.; Ligabue, G. (1993). On the presence of a giant pterosaur in the Lower Cretaceous (Aptian) of Chapada do Araripe (northeastern Brazil) (PDF). Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana. 32. pp. 131–136.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Ross A. Elgin & Eberhard Frey (2011). "A new ornithocheirid, Barbosania gracilirostris gen. et sp. nov. (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) from the Santana Formation (Cretaceous) of NE Brazil". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 130 (2): 259–275. doi:10.1007/s13358-011-0017-4.

- Renan A. M. Bantim; Antônio A. F. Saraiva; Gustavo R. Oliveira; Juliana M. Sayão (2014). "A new toothed pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea: Anhangueridae) from the Early Cretaceous Romualdo Formation, NE Brazil". Zootaxa. 3869 (3): 201–223. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3869.3.1. PMID 25283914.

- Veldmeijer, A.J., Meijer, H.J.M. & Signore, M. (2009). "Description of Pterosaurian (Pterodactyloidea: Anhangueridae, Brasileodactylus) remains from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil". DEINSEA. 13: 9–40.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Leonardi, G. & Borgomanero, G. (1985). "Cearadactylus atrox nov. gen., nov. sp.: novo Pterosauria (Pterodactyloidea) da Chapada do Araripe, Ceara, Brasil." Resumos dos communicaçoes VIII Congresso bras. de Paleontologia e Stratigrafia, 27: 75–80.

- Martill, David M. (2011). "A new pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Santana Formation (Cretaceous) of Brazil". Cretaceous Research. 32 (2): 236–243. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2010.12.008.

- Kellner, A.W.A.; Campos, D.A. (2007). "Short note on the ingroup relationships of the Tapejaridae (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea". Boletim do Museu Nacional. 75: 1–14.

- Pêgas, R. V.; Costa, F. R.; Kellner, A. W. A. (2018). "New Information on the osteology and a taxonomic revision of The genus Thalassodromeus (Pterodactyloidea, Tapejaridae, Thalassodrominae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (2): e1443273. doi:10.1080/02724634.2018.1443273.

- Witton, Mark P. (October 2009). "A new species of Tupuxuara (Thalassodromidae, Azhdarchoidea) from the Lower Cretaceous Santana Formation of Brazil, with a note on the nomenclature of Thalassodromidae". Cretaceous Research. 30 (5): 1293–1300. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2009.07.006.

- Kellner, A.W.A.; Campos, D.A. (1996). "First Early Cretaceous theropod dinosaur from Brazil with comments on Spinosauridae". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 199 (2): 151–166. doi:10.1127/njgpa/199/1996/151.

- Martill, D.M.; Cruickshank, A.R.I.; Frey, E.; Small, P.G.; Clarke, M. (1996). "A new crested maniraptoran dinosaur from the Santana Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of Brazil". Journal of the Geological Society. 153 (1): 5–8. Bibcode:1996JGSoc.153....5M. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.153.1.0005.

- Ortega, F. J.; Z. B. Gasparini; A. D. Buscalioni; J. O. Calvo (2000). "A new species of Araripesuchus (Crocodylomorpha, Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Lower Cretaceous of Patagonia (Argentina)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 20 (1): 57–76. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0057:ANSOAC]2.0.CO;2.

- Zug, George R. "Turtle: Origin and evolution". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- Hirayama, Ren (1998-04-16). "Oldest known sea turtle". Nature. 392 (6677): 705–708. doi:10.1038/33669.

- Lane, Jennifer A.; Maisey, John G. (2012). "The Visceral Skeleton and Jaw Suspension In the Durophagous Hybodontid Shark Tribodus limae from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil". Journal of Paleontology. 86 (5): 886–905. doi:10.1666/11-139.1. ISSN 0022-3360.

- Paulina-Carabajal, A.; Lee, Y.N.; Jacobs, L.L. (2016). "Endocranial Morphology of the Primitive Nodosaurid Dinosaur Pawpawsaurus campbelli from the Early Cretaceous of North America". PLoS ONE. 11 (3): e0150845. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150845. PMC 4805287. PMID 27007950.

- Coombs, W. P. 1995. A nodosaurid ankylosaur (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Lower Cretaceous of Texas. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 15(2):298-312. doi:10.1080/02724634.1995.10011231

- Weishampel, David B; et al. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Early Cretaceous, North America)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 553-556. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- William A.C. (1969). The Late Cretaceous Ammonites Scaphites leei Reeside and Scaphites hippocrepis (DeKay) in the Western Interior of the United States (PDF). United States Government Printing Office. pp. 3–7.

- Cappetta H. 1987. Chondrichthyes II. Mesozoic and Cenozoic Elasmobranchii. Schultze H.-P. (ed.), Handbook of Paleoichthyology, Volume 3B. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart, 193 p.

Further reading

- Wellnhofer, Peter (1991). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pterosaurs: An illustrated natural history of the flying reptiles of the Mesozoic Era. Crescent Books. ISBN 0517037017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Witton, Mark (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691150611.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)