Orangutan–human last common ancestor

The phylogenetic split of Hominidae into the subfamilies Homininae and Ponginae is dated to the middle Miocene, roughly 18 to 14 million years ago. This split is also referenced as the "orangutan–human last common ancestor” by Jeffrey H. Schwartz, professor of anthropology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Arts and Sciences, and John Grehan, director of science at the Buffalo Museum.

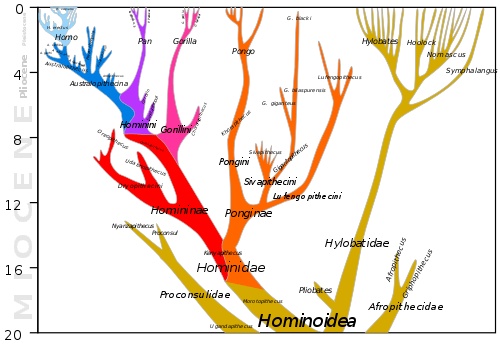

Phylogeny

Below is a cladogram with extinct species.[1][2][3]

| Hominidae (18) |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hominoidea (apes) are thought to have evolved in Africa by about 18 million years ago. Among the genera thought to be in the ape lineage leading up to the emergence of the great apes (Hominidae) about 13 million years ago are Proconsul, Rangwapithecus, Dendropithecus, Nacholapithecus, Equatorius, Afropithecus and Kenyapithecus, all from East Africa. During the early Miocene, Europe and Africa were connected by land bridges over the Tethys Sea. Apes show up in Europe in the fossil record beginning 17 million years ago. Great apes show up in the fossil record in Europe and Asia beginning about 12 million years ago.[4] The only living great ape in Asia is the orangutan.[5]

Various genera of dryopithecines have been identified and are classified as an extinct sister clade of the Homininae.[6]:226 Dryopithecines was first uncovered in France and it had a large frontal sinus which ties it to the African great apes.[5] Orangutans which are only found in Asia do not.[5] They did have thick dental enamel another ape-like characteristic.[5]

The study of Dryopithecini as an outgroup to Hominidae suggests a date earlier than 8 million years ago for the Homininae-Ponginae split. It also suggests that the Homininae group evolved in Africa or Western Eurasia, against the theory that Homininae were originally an Asian line which later recolonized Africa after the Great Apes went extinct in Africa.[7]

During the later Miocene the climate in Europe started to change as the Himalayas were rising and European became cooler and drier. About 9.5 million years ago tropical forest in Europe was replaced by woodlands which were less suitable for great apes and European Homininae (close to the Dryopithecini-Hominini split) appear to have migrated back to Africa where they would have diverged into Gorillini and Hominini.[5]

Appearance and ecology

The orangutan–human last common ancestor was tailless, and had a broad flat rib cage. The orangutan–human last common ancestor had a larger body size, larger brain, and in females, the canine teeth had started to shrink like their descendants.[6]:201 Great apes have sweat glands in their armpit versus in their chest like lesser monkeys.[6]:195

Orangutans have anterior lingual glands and sparse terminal hair like the hominines.[6]:193

Terminal hairs are those hairs that are easy to see. As compared to the tiny light colored hairs called Vellus hairs. Certainly there is some correlation with the size of the mammal. The larger the mammal the fewer terminal hairs.[6]:195

Near the tip of the tongue on the underside are the submandibular glands which secrete amylase. These are only found in the great apes so it is understood that the last common ancestor would also have these.[6]:195

With regard to the skull this is an example where humans share more in common with orangutans than with later great apes. We have two small ridges, one over each eye called superciliary arches.[6]:229

The great apes other than humans and orangutans have brow ridges.[6]:229

References

- Grabowski, Mark; Jungers, William L. (2017). "Evidence of a chimpanzee-sized ancestor of humans but a gibbon-sized ancestor of apes". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 880. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00997-4. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5638852. PMID 29026075.

- Nengo, Isaiah; Tafforeau, Paul; Gilbert, Christopher C.; Fleagle, John G.; Miller, Ellen R.; Feibel, Craig; Fox, David L.; Feinberg, Josh; Pugh, Kelsey D. (2017). "New infant cranium from the African Miocene sheds light on ape evolution". Nature. 548 (7666): 169–174. doi:10.1038/nature23456. PMID 28796200.

- Malukiewicz, Joanna; Hepp, Crystal M.; Guschanski, Katerina; Stone, Anne C. (2017-01-01). "Phylogeny of the jacchus group of Callithrix marmosets based on complete mitochondrial genomes". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 162 (1): 157–169. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23105. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 27762445.

Fig 2: Divergence time estimates for the jacchus marmoset group based on the BEAST4 (Di Fiore et al., 2015) calibration scheme for alignment A.[...] Numbers at each node indicate the median divergence time estimate.

- Dawkins, Richard; Wong, Yan (2016). The Ancestor's Tale. ISBN 978-0544859937.

- Wayman, Erin. "Did Africa's Apes Come From Europe?". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- Kane, Jonathan; Willoughby, Emily; Michael Keesey, T. (2016-12-31). God's Word or Human Reason?: An Inside Perspective on Creationism. ISBN 9781629013725.

- Kunimatsu, Y.; et al. (2007). "A new Late Miocene great ape from Kenya and its implications for the origins of African great apes and humans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (49): 19220–19225. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706190104. PMC 2148271. PMID 18024593.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

See also

- History of hominoid taxonomy

- Gibbon–human last common ancestor

- Gorilla–human last common ancestor

- Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor

- List of human evolution fossils