One Million Years B.C.

One Million Years B.C. is a 1966 British adventure fantasy film directed by Don Chaffey. The film was produced by Hammer Film Productions and Seven Arts, and is a remake of the 1940 American fantasy film One Million B.C.. The film stars Raquel Welch and John Richardson, set in a fictional age of cavemen and dinosaurs. Location scenes were filmed on the Canary Islands in the middle of winter, in late 1965. The British release prints of this film were printed in dye transfer Technicolor. The US version was cut by 9 minutes,[3] printed in DeLuxe Color, and released in 1967.[4]

| One Million Years B.C. | |

|---|---|

British theatrical release poster by Tom Chantrell | |

| Directed by | Don Chaffey |

| Produced by | Michael Carreras |

| Written by | Michael Carreras[1] |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Mario Nascimbene |

| Cinematography | Wilkie Cooper |

| Edited by | Tom Simpson |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 100 minutes (United Kingdom) 91 minutes (United States) |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £422,816[2] |

| Box office | $8 million (United States)[2] |

Like the original film, this remake is largely ahistorical. It portrays dinosaurs and humans living at the same point in time; according to the geologic time scale, the last non-avian dinosaurs became extinct 66 million years ago, and modern humans, Homo sapiens, did not exist until about 200,000 years BC. Ray Harryhausen, who animated all of the dinosaur attacks using stop motion techniques, commented on the US King Kong DVD that he did not make One Million Years B.C. for "professors... who probably don't go to see these kinds of movies anyway."

Plot

Tribal chief Akhoba leads a hunting party into the hills to search for prey. One member of the tribe traps a warthog in a pit, and then Akhoba's son Tumak kills it. The tribe brings it home for dinner. Tumak and Akhoba fight over who deserves more of the meat, and Tumak is banished to the harsh desert by his angry father. After surviving many dangers such as a giant iguana, ape men, Brontosaurus, and a giant spider, he collapses on a remote beach along the Western Interior Seaway, where he is spotted by "Loana the Fair One" and her fellow fisher-women of the blond Shell Tribe. They are about to help him when an Archelon (which is three times the size of the actual prehistoric Archelon) makes its way to the beach. Men of the Shell tribe arrive and drive it into the sea. Tumak is taken to their village, where Loana tends to him. Scenes follow emphasising that the Shell tribe is more advanced and more civilized than the brunette Rock tribe. They have cave paintings, music, delicate jewelry made from shells, agriculture, and a rudimentary language–all things Tumak seems to have never before encountered.

When the tribe women are fishing, a young Allosaurus attacks. The tribe flees to their cave, but in the panic, a small girl is left trapped up a tree. Tumak seizes a spear from Ahot, a man of the Shell tribe, and rushes forward to defend her. Emboldened by this example, Loana runs out to escort the child to safety, and Ahot and other men come to Tumak's aid, one of the men being killed before Tumak is finally able to kill the dinosaur. In the aftermath, a funeral is held for the dead men – a custom which Tumak disdains. Leaving the funeral early, he re-enters the cave, and attempts to steal the spear with which he had killed the Allosaurus. Ahot, who had taken back the spear, enters, feeling upset by the attempted theft, and a fight ensues. The resulting commotion attracts the rest of the tribe, who unite to cast Tumak out. Loana leaves with him, and Ahot, in a gesture of friendship, gives him the spear over which they had fought.

Meanwhile, Akoba leads a hunting party into the hills to search for prey but loses his footing while trying to take down a ram. Tumak's brother Sakana tries to kill their father to take power. Akoba survives, but is a broken man. Sakana becomes the new leader. With Sakana at the helm, Tumak and Loana run into a battle between a Ceratosaurus (as with the Archelon, the Ceratosaurus is twice the size as the actual creature) and a Triceratops; the Triceratops eventually wins, charging its opponent and leaving it stunned. The outcasts wander back into the Rock tribe's territory and Loana meets the tribe, but again, there are altercations. The most dramatic one is a fight between Tumak's current love interest Loana and his former lover "Nupondi the Wild One". Loana wins the fight but refuses to strike the killing blow, despite the encouragement of the other members of the tribe. Meanwhile, Sakana resents Tumak and Loana's attempts at incorporating Shell tribe ways into their culture.

While the cave people are swimming – seemingly for the first time, and inspired by Loana's example – they are attacked by a female Pteranodon. In the confusion, Loana is snatched into the air by the creature to be fed to its offspring, but is instead dropped into the sea, due to the intervention of a giant thieving Rhamphorhynchus. Loana manages to stagger ashore while the two pterosaurs battle, and then falls down. Tumak arrives but is only greeted by the sounds of the victorious Rhamphorhynchus eating the Pteranodon's offspring.

Tumak initially presumes Loana to be dead. Sakana then leads a group of like-minded fellow hunters in an armed revolt against Akoba. Tumak, Ahot and Loana (who had staggered back to her tribe after the Pteranodon dropped her into the sea), and other members of the Shell tribe arrive in time to join the fight against Sakana. In the midst of a savage hand-to-hand battle, a volcano suddenly erupts: the entire area is stricken by earthquakes and landslides that overwhelm both tribes. As the film ends, Tumak, Loana, and the surviving members of both tribes emerge from cover to find themselves in a ruined, near-lunar landscape. They all set off – now united – to find a new home.

Cast

- Raquel Welch as Loana

- John Richardson as Tumak

- Percy Herbert as Sakana

- Robert Brown as Akhoba

- Martine Beswick as Nupondi

- Jean Wladon as Ahot

Production

The exterior scenes were filmed on Lanzarote and Tenerife in the Canary Islands in the middle of winter. The film features the Echium wildpretii plant, as a homage to Tenerife's unique endemic flora. However, the plants are set in scenes filmed on the Lanzarote beach. In actuality, this plant only flowers from May to June. It is found in Tenerife mountain zones higher than 1,600 m (5,200 ft). As there were no active volcanoes in the Canary Islands, the studio had to construct a 6–7 ft (2-meter) high volcano on the Associated British Picture Corporation's studio back lot. The eruption, lava explosions and lava flows were composed of a mixture of wallpaper paste, oatmeal, dry ice and red dye. Harryhausen filmed the dinosaur visuals in his personal studio in London.

As the Shell people are attacked by a giant turtle, the women call it Archelon which is the real scientific name for the animal. The film uses three live creatures: a green iguana, a warthog, and a tarantula (a cricket can be seen at the tarantula's side). Ray Harryhausen was asked repeatedly about these unanimated creatures, and he confessed they were his idea. At the time, he felt the use of real creatures would convince the audience that all of what they were about to see was indeed real.

Shortly after, Tumak encounters a dinosaur skeleton, which helped build audience anticipation for further dinosaur encounters. This supposedly massive skeleton was actually only about 12 inches in length, made of plaster and shot against a blue backing and matted into the foreground.

The scene where the young Allosaurus attacks the village is similar to one in the original film. Shortly after the creature appears it plucks a man out of the water. They used an actor suspended on wires and Harryhausen positioned an animated model man over the actor, on the rear projection plate; thus it seemed as if the live actor was being eaten. Another technically complex scene in this part of the film was when a man fighting the young Allosaurus is trapped under a shelter: the dinosaur grabs a support and collapses it. The team used a full-size shelter rigged to collapse at that point during the action. Harryhausen then placed a miniature part in the creature's mouth which, when all lined up on the rear projection plate, blended in perfectly. The final significant scene in this sequence is when Tumak impales the creature on a spear from below. John Richardson, the actor who played Tumak, held nothing in the long shots and pretended to have a pole in his hands, but he did hold a pole in the close-up shots. A miniature pole was built and used for the long shots. It was placed in the studio in front of Richardson's hands, and then Ray animated the young Allosaurus suspended on wires in front of John, on top of the miniature pole.

The Pteranodon sequence took much time to create, primarily because of how hard it would be to make a model pterosaur pick up a real woman. However the solution was simple: Instead of using a large crane on location, the crew had Raquel Welch fall behind a rock, and then the model Pteranodon swoops down and flies off with a model of Welch, which was substituted during the single second in which she is behind the rock and not visible. Later, when the creature takes her to its nest, the nest was matted into the scene atop a real rock face by double printing the film. For the Pteranodon and Rhamphorhynchus fight scene, when she is dropped into the water, Harryhausen and the crew released her from two dummy rubber Pteranodon claws and while the real Welch fell onto a mattress, the film cut to a long shot of the Welch model suspended on wires.[6]

Robert Brown (Akhoba) wears makeup similar to that worn by Lon Chaney, Jr. in the same role in the 1940 version, One Million B.C.

Originally Hammer offered the role of Loana to Ursula Andress. When Andress passed on the project due to commitments and salary demands, a search for a replacement resulted in the selection of Welch.[7] Welch, who had finished doing Fantastic Voyage for Fox, was under contract to the studio (who held U.S. distribution rights for the film) and was told by studio President Richard Zanuck that she would be loaned out to Hammer for the production. Although reluctant, Welch said that the selling point was the chance to spend six to eight weeks of filming in London (while shooting interiors) during the height of its "swinging" period.[8]

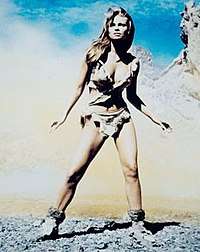

Fur bikini

Welch wore a bikini made of fur and hide in the film. She was described as "wearing mankind's first bikini" and the bikini was described as a "definitive look of the 1960s". The publicity photograph of Welch from the film became a best-selling pinup poster,[9] and something of a cultural phenomenon.[10][11]

The iconic image was copied by the artist Tom Chantrell to create the film poster promoting the theatrical release of One Million Years BC. Welch's depiction is accompanied by the film's title in bold red lettering across a landscape populated with dinosaurs.[12]

Welch stated in a 2012 interview that three form-fitting bikinis were made for her, including two for a wet scene and a fight scene, by costume designer Carl Toms: "Carl just draped me in doe-skin, and I stood there while he worked on it with scissors." Many noted photographers had been flown to Tenerife by 20th Century Fox on a publicity junket, but the iconic pose of Welch was taken by the unit still photographer.[13] The poster was a story element in the film The Shawshank Redemption.[14][15]

Music

Composer Mario Nascimbene was in charge of the films music and score. The soundtrack was released in Italy as a 7-track limited edition vinyl LP on the Intermezzo label in 1985.[16] It was re-released in Italy on compact disc in 1994 and now out of print, as a soundtrack compilation with two other Hammer films included.[17] The original score for the film:

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Cosmic Sequence" | 3:44 |

| 2. | "Lunar Landscape" | 1:51 |

| 3. | "Tumak meets Loana" | 3:45 |

| 4. | "Tumak in the Domain of the Shell tribe" | 5:24 |

| 5. | "Dance of Dupondi" | 1:16 |

| 6. | "The Pteranodon Carries Loana to its Nest" | 4:35 |

| 7. | "Tumak rescues Loana/Eruption of the Volcano/Finale" | 9:33 |

| Total length: | 30:08 | |

Release

It was first screened on 25 October, 1966 at the London Trade Show with a general release in the United Kingdom on 30 December, 1966 by Warner-Pathé and the United States on 21 February, 1967 by 20th Century Fox.[18] The U.S. cut was censored for a broader audience, losing around nine minutes. Deleted scenes included a provocative dance from Martine Beswick, a gruesome end to one of the ape men in the cave and some footage of the young Allosaurus' attack on the Shell tribe. On 17 October, 1966, the British Board of Film Classification announced that the film would receive an A certificate rating. It is currently a PG certificate applied on video in March 1989 distributed by Warner Home Video Ltd.[19]

Home media

The film was originally available on VHS and laserdisc.[20] In 2002 Warner Bros. released a U.K. DVD, including a "Raquel Welch in the Valley of the Dinosaurs" featurette, a twelve-minute interview with Ray Harryhausen and theatrical trailer.[21]

In October 2016, a special 2-disc 50th anniversary edition DVD and Blu-ray was released in the U.K. by Studio Canal, with new interviews with Welch and Beswick, new Ray Harryhausen storyboard stills, and other promotional imagery.[22] In the United States a Blu-ray was released on 14 February, 2017 by Kino Lorber Studio Classic and includes the international (Disc 1) and U.S. cut (Disc 2) of the film. This issue has more bonus material than the U.K. edition including previous interviews with Welch and Harryhausen from 2002 and an audio commentary by film historian Tim Lucas.[23]

Reception

Box office

Despite the censorship upon release in the U.S., the film was still popular and made $2.5 million in U.S. rentals during its first year of release.[24][25]

According to Fox records, the film needed to earn $2,250,000 in rentals to break even and made $4,425,000, meaning it made a solid profit.[26]

In 1968, it was re-released in the U.K. on a double bill alongside She (1965), an earlier Hammer film. The pairing became the ninth most popular theatrical release of the year.[27]

Critical response

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 62% based on 14 reviews, with an average rating of 5.64/10.[28] Among contemporary reviews, Variety wrote "the whole thing is good humored full-of-action commercial nonsense, but the moppets will love it and older male moppets will probably love Miss Welch";[29] and The Monthly Film Bulletin noted "Very easy to dismiss the film as a silly spectacle; but Hammer production finesse is much in evidence and Don Chaffey has done a competent job of direction. And it is all hugely enjoyable";[30] while more recently, The Times wrote that "seen nowadays it is a kitschy, retro scream. Yet as dinosaurs and giant sea-turtles roam the volcanic earth in One Million Years BC, this is also a chance to appreciate the early work of the great special effects pioneer Ray Harryhausen."[31] and similarly, TV Guide concluded "While far from being one of Harryhausen's best films (the quality of which had little to do with his abilities), the movie has superb effects that are worth a look for his fans."[32]

Legacy

All the dinosaur models from this film still exist, although the Ceratosaurus and Triceratops were re-purposed for The Valley of Gwangi (1969), as Gwangi the Tyrannosaurus and the Styracosaurus. One Million Years B.C. was the first in an unconnected series of prehistoric films from Hammer. It was followed by Prehistoric Women (1968), When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970) and Creatures the World Forgot (1971).[33] Stock footage depicting the landslide was reused for Alex's daydream scene in Stanley Kubrick's 1971 film A Clockwork Orange.[34]

In other media

The film was adapted into a 15-page comic strip for the May 1978 issue of the magazine House of Hammer (volume 2, # 14, published by Top Sellers Limited). It was drawn by John Bolton from a script by Steve Moore. The cover of the issue featured a painting by Brian Lewis of Raquel Welch in the famous fur bikini.

In the 1994 film The Shawshank Redemption, a large poster of Raquel Welch, in her role as Loana is used by Andy Dufresne (played by Tim Robins) to conceal his tunnel digging.

See also

References

- http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/443654/index.html

- Marcus Hearn & Alan Barnes, The Hammer Story: The Authorised History of Hammer Films, Titan Books, 2007 p 105

- "One Million Years B.C. - Alternate Versions". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- "One Million Years B.C. - Original Print Information". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- "Greatest Opening Film Lines and Quotes 1950s - 1960s". filmsite.org.

- Ray Harryhausen: An Animated Life pgs 194-202

- Smith, Gary A. (1991). Epic Films: Casts, Credits and Commentary on over 250 Historical Spectacle Movies. Mcfarland & Co. p. 162. ISBN 978-0899505671. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- Newsom, Ted (Spring 1993). "Raquel Welch". Femme Fatales.

- Mansour, David (2005). From Abba to Zoom: a pop culture encyclopedia of the late 20th century. Andrews McMeel Publishing. p. 345. ISBN 978-0-7407-5118-9. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- Filmfacts. 1967. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- Gayomali, Chris (5 July 2011). "Top 10 Bikinis in Pop Culture". Time. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- Wigley, Samuel (23 November 2016). "Amicus and the art of the film poster". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- Spitznagel, Eric (8 March 2012). "Interview with Raquel Welch". Men's Health. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- Carr, Jay (23 September 1994). "Captivating Shawshank". The Boston Globe. Highbeam Research. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. (subscription required)

- Harvey, Neil (7 October 2004). "Shawshank Redemption gets the treatment it deserves". The Roanoke Times. Highbeam Research. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. (subscription required)

- Larson, Randall D. "Music from the House of Hammer, Music in the Hammer Horror Films 1950-1980". Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- Webber, Roy P. "The Dinosaur Films of Ray Harryhausen, Features, Early 16mm Experiments". Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- Fellner, Chris. "The Encyclopedia of Hammer Films". Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "ONE MILLION YEARS B.C. (1966)". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "One Million Years B.C. (1966) Laserdisc". Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "One Million Years B.C DVD United Kingdom Warner Bros". Blu-ray.com. 29 July 2002. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "One Million Years B.C. 50th Anniversary Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. October 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- "One Million Years B.C. Blu-ray United States 1966, 1 Movie, 2 Cuts, 100 min". 14 February 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- Solomon, Aubrey (1989). Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History (The Scarecrow Filmmakers Series). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-8108-4244-1.

- "Big Rental Films of 1967", Variety, 3 January 1968 p 25. Please note these figures refer to rentals accruing to the distributors.

- Silverman, Stephen M (1988). The Fox that got away : the last days of the Zanuck dynasty at Twentieth Century-Fox. L. Stuart. p. 326.

- "The World's Top Twenty Films." Sunday Times [London, England] 27 September 1970: 27. The Sunday Times Digital Archive. accessed 5 April 2014

- One Million Years B.C. (1967) Rotten Tomatoes

- Gold, Rich (22 December 1966). "One Million Years B.C."

- "Monthly Film Bulletin review". screenonline.org.uk.

- Muir, Kate (21 October 2016). "Classic film of the week: One Million Years BC (1966)". thetimes.co.uk.

- "One Million Years B.C." TVGuide.com.

- McKay, Sinclair (2007). A Thing of Unspeakable Horror: The History of Hammer Films. Aurum. p. 105. ISBN 978-1845133481.

- Hughes, David (31 May 2013). "The Complete Kubrick". Random House – via Google Books.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: One Million Years B.C. |