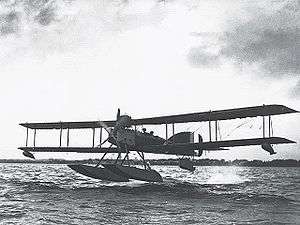

Observation seaplane

Observation seaplanes are military aircraft with floatation devices allowing them to land on and take off from water. Their primary purpose was to observe and report enemy movements or to spot the fall of shot from naval artillery, but some were armed with machineguns or bombs. Their military usefulness extended from World War I through World War II. They were typically single-engine machines with a crew of one, two or three. Many were designed to be carried aboard warships, but they also operated from seashore harbors.

.jpg)

Catapult procedures

The pilot and observer would climb into their aircraft and rev the engine at full throttle. If the instrument panel readings were satisfactory, the pilot would brace for takeoff and signal the catapult operator he was ready. The United States Navy 30 ft (9.1 m) catapult used a smokeless powder charge to accelerate the plane to 80 mi (130 km) per hour.[2] (0 to 80 in one-half second)

A capital ship preparing to recover its aircraft would steam into the wind and signal the aviator which way it would turn across the wind to provide a sheltered landing surface. When the plane was in position the ship would turn so the plane could land on the lee side as close as possible to the ship. The ship would tow a net along the water surface from a boom on the lee side, and the plane would taxi over the net so a hook on the underside of the float would engage the net allowing the plane to cut power and minimize relative movement of the plane with respect to the ship while the ship's crane hoisted the plane aboard.[2]

United States

Two early aircraft assembled by Glenn Curtiss prior to formation of the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company arrived aboard USS Mississippi on 24 April 1914 under the command of Henry Mustin to conduct aerial reconnaissance during the United States occupation of Veracruz. This was the first operational use of naval aircraft and the first time U.S. aviators of any service were the target of ground fire.[3] On 5 November 1915 Mustin pioneered United States Navy catapult operations piloting an AB-2 seaplane launched from the cruiser USS North Carolina. Interest in aerial observation increased as combat experience during first world war naval engagements demonstrated the inability of shipboard observers to accurately report fall of shot from the engagement range of dreadnought battleships. Nine Vought VE-7s were delivered in 1924 to be launched from battleship catapults. Subsequent design improvements were the Vought FU and Vought O2U Corsair. A few Berliner-Joyce OJ float planes were built for the Omaha class light cruiser catapults. The Curtiss SOC Seagull became the dominant United States Navy catapult seaplane in 1935, until the number of Vought OS2U Kingfishers manufactured during the second world war exceeded the total production of all previous United States Navy observation seaplanes. In the absence of gunnery engagements with other warships, capital ships' observation seaplanes were used to spot naval gunfire support; but they proved so vulnerable to land-based fighters during the amphibious invasion of Sicily that their pilots flew conventional fighters spotting gunfire for the invasion of Normandy. A few Curtiss SC Seahawks remained operational into the late 1940s until helicopters became reliable enough to replace observation seaplanes.[2]

United Kingdom

The first seaplane used in a naval battle was a Short Type 184 launched from HMS Engadine in the opening stages of the 1916 Battle of Jutland. The plane was forced down by a broken fuel line after locating a few cruisers, and the clumsy procedure of finding calm water to offload and launch took so long that Engadine's other planes were unable to meaningfully participate.[4] This experience encouraged development of the Fairey III to be operated from aircraft carriers. The Supermarine Seagull II was the first British aircraft to be catapult launched in 1925. This design was improved as the Supermarine Walrus serving aboard capital ships of the Royal Navy through the second world war. Royal Navy preference for the Walrus' flying boat fuselage was unusual among the shipboard observation seaplanes of the major naval powers.

Japan

When the Washington Naval Treaty left Japan with fewer capital ships than the United States or the United Kingdom, the country focused on aviation as a means of balancing naval power. Although only the Mitsubishi F1Ms were officially designated observation seaplanes, there were numerous similar reconnaissance seaplanes prefixed with the letter E rather than F. Japan produced observation and reconnaissance seaplanes in larger numbers and greater diversity than any other nation. The first Japanese design was the Nakajima E2N in 1927. Increasing numbers of Nakajima E4Ns, Kawanishi E7Ks, and Nakajima E8Ns were manufactured before the Aichi E13A was produced in similar numbers to the American OS2U Kingfisher. Each of the Tone class cruisers carried six seaplanes for the Kidō Butai reconnaissance role to allow the full complement of aircraft carrier planes to focus on their attack role. In addition to launching from capital ships, these Japanese seaplanes operated from fast seaplane tenders providing aviation support similar to aircraft carriers during amphibious operations.[5] The Yokosuka E6Y, Watanabe E9W and Yokosuka E14Y were specially designed to be carried and launched by submarines.[6]

Germany

German rearmament in the 1930s included Heinkel He 60, Heinkel He 114 and Arado Ar 196 float planes for launch from the catapults of the Kriegsmarine's capital ships. A few later operated aboard merchant raiders.[7]

Comparison of ship-launched seaplanes

The following is not an exhaustive list, but compares the observation and reconnaissance seaplanes produced in greatest numbers.

| Name | Nation | Type | Span | Length | Power | Produced | Number built |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kawanishi E7K | Japan | Twin-float biplane | 46 ft (14 m) | 34 ft (10 m) | 870 hp (650 kW)[8] | 1935-1941 | 733 |

| Curtiss SOC Seagull | United States | Single-float biplane | 36 ft (11 m) | 32 ft (9.8 m) | 550 hp (410 kW)[9] | 1935-1940 | 322 |

| Nakajima E8N | Japan | Single-float biplane | 36 ft (11 m) | 29 ft (8.8 m) | 630 hp (470 kW)[10] | 1935-1940 | 755 |

| Supermarine Walrus | United Kingdom | Biplane flying boat | 46 ft (14 m) | 38 ft (12 m) | 775 hp (578 kW)[11] | 1936-1944 | 775 |

| Arado Ar 196 | Germany | Twin-float monoplane | 41 ft (12 m) | 36 ft (11 m) | 960 hp (720 kW)[12] | 1938-1944 | 541 |

| Vought OS2U Kingfisher | United States | Single-float monoplane | 36 ft (11 m) | 34 ft (10 m) | 450 hp (340 kW)[9] | 1940-1944 | 1519 |

| Mitsubishi F1M | Japan | Single-float biplane | 36 ft (11 m) | 31 ft (9.4 m) | 875 hp (652 kW)[13] | 1941-1944 | 944 |

| Aichi E13A | Japan | Twin-float monoplane | 48 ft (15 m) | 37 ft (11 m) | 1,060 hp (790 kW)[14] | 1941-1944 | 1418 |

| Aichi E16A | Japan | Twin-float monoplane | 42 ft (13 m) | 36 ft (11 m) | 1,300 hp (970 kW)[15] | 1944-1945 | 256 |

| Curtiss SC Seahawk | United States | Single-float monoplane | 41 ft (12 m) | 38 ft (12 m) | 1,350 hp (1,010 kW)[9] | 1944-1945 | 577 |

Sources

- Watts, Anthony J. (1967). Japanese Warships of World War II. New York: Doubleday & Company. pp. 311–315.

- Stinson, Patrick (1986). "Eyes of the Battle Fleet". Proceedings. United States Naval Institute. Supplement (April): 87–89.

- Owsley, Frank L., Jr.; Newton, Wesley Phillip (1986). "Eyes in the Skies". Proceedings. United States Naval Institute. Supplement (April): 17–25.

- Potter, E.B.; Nimitz, Chester W. (1960). Sea Power. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. p. 635.

- Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy (1941-1945). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 14, 55, 71, 72 & 114.

- Collier, Basil (1979). Japanese Aircraft of World War II. New York: Mayflower Books. pp. 46, 59, 62, 101, 119 & 137. ISBN 0-8317-5137-1.

- Wood, Tony; Gunston, Bill. Hitler's Luftwaffe. New York: Crescent Books. pp. 126 & 185. ISBN 0-517-22477-1.

- Collier, Basil (1979). Japanese Aircraft of World War II. New York: Mayflower Books. pp. 62 & 63. ISBN 0-8317-5137-1.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1962). History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Fifteen. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 114.

- Collier, Basil (1979). Japanese Aircraft of World War II. New York: Mayflower Books. pp. 119 & 120. ISBN 0-8317-5137-1.

- Gunston, Bill (1989). Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II. New York: Crescent Books. pp. 142 & 143. ISBN 0-517-67964-7.

- Wood, Tony; Gunston, Bill (1977). Hitler's Luftwaffe. New York: Crescent Books. pp. 126 & 127. ISBN 0-517-22477-1.

- Collier, Basil (1979). Japanese Aircraft of World War II. New York: Mayflower Books. p. 101. ISBN 0-8317-5137-1.

- Collier, Basil (1979). Japanese Aircraft of World War II. New York: Mayflower Books. pp. 59 & 60. ISBN 0-8317-5137-1.

- Collier, Basil (1979). Japanese Aircraft of World War II. New York: Mayflower Books. p. 60. ISBN 0-8317-5137-1.