OV2-1

Orbiting Vehicle 2-1 (COSPAR ID: 1965-82C, also known as OV2-1), was the first satellite of the second iteration of the United States Air Force's Orbiting Vehicle program. OV2-1 was an American life science research satellite designed for long-term measurement of radiation in orbit. Launched October 15, 1965, the mission resulted in failure when the upper stage of OV2-1's Titan IIIC booster broke up.[2]

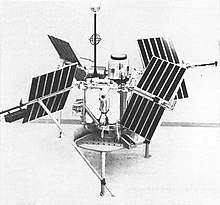

Image of Orbiting Vehicle (OV) 2-1 | |

| Mission type | Life science |

|---|---|

| Operator | USAF |

| COSPAR ID | 1965-082C |

| SATCAT no. | 01641 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Northrop |

| Launch mass | 170 kg (370 lb) |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 15 October 1965, 17:23:59 UTC |

| Rocket | Titan IIIC |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral LC40[1] |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Eccentricity | 0.00603 |

| Perigee altitude | 706 km (439 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 792 km (492 mi) |

| Inclination | 32.6° |

| Period | 99.7 minutes[2] |

| Epoch | 15 October 1965 |

History

In the early 1960s, the US Air Force initiated an effort to reduce the expense of space research. Satellite production was standardized to improve reliability and cost-efficiency. The research satellites would fly on test vehicles or be piggybacked with other satellites. In 1961, the Air Force Office of Aerospace Research (OAR) created the Aerospace Research Support Program (ARSP) to request satellite research proposals and choose mission experiments. The USAF Space and Missiles Organization created their own analog of the ARSP called the Space Experiments Support Program (SESP), which sponsored a greater proportion of technological experiments than the ARSP.[3]:417

The OV2 series of satellites was originally designed as part of the ARENTS (Advanced Research Environmental Test Satellite) program, intended to obtain supporting data for the Vela satellites, which monitored the Earth for violations of the 1963 Partial Test Ban Treaty. Upon the cancellation of ARENTS due to delays in the Centaur rocket stage, the program's hardware (developed by General Dynamics) was repurposed to fly on the Titan III [3]:422 (initially the A,[4] ultimately the C) booster test launches.[3]:422 The USAF contracted Northrop to produce these satellites, with William C. Armstrong of Northrop Space Laboratories serving as the program manager.[4]

Spacecraft design

The OV2 satellites were all designed on the same plan, roughly cubical structures of aluminum honeycomb, .61 m (2.0 ft) in height, and .58 m (1.9 ft) wide, with four 2.3 m (7.5 ft) paddle-like solar panels mounted at the four upper corners, each with 20,160 solar cells. The power system, which included NiCd batteries for night-time operations, provided 63 W of power. Experiments were generally mounted outside the cube while satellite systems, including tape recorder, command receiver, and PAM/FM/FM telemetry system, were installed inside. Four small solid rocket motors spun, one on each paddle, were designed to spin the OV2 satellites upon reaching orbit, providing gyroscopic stability. Cold-gas jets maintained this stability, receiving information on the satellite's alignment with respect to the Sun via an onboard solar aspect sensor, and with respect to the local magnetic field via two onboard fluxgate magnetometers. A damper kept the satellite from precessing (wobbling around its spin axis). Passive thermal control kept the satellite from overheating.[3]:422

Experiments

The first OV2 satellite was designed to evaluate the long-term hazards of the Earth's Van Allen radiation belts to astronauts and satellites.[5] Over the course of a year-long mission, the solar-powered satellite would measure nuclear particles, electromagnetic field strength, very low frequency radio waves, and radiation effects on tissue equivalents.[4]

The Air Force's Cambridge Research Center, Weapons Laboratory, and Aerospace Corporation[4] designed the 59 kg (130 lb) scientific and engineering experiment package of fourteen instruments.[3]:422 In addition to biological tissue equivalents, they included a Cerenkov Counter, a charged particle flux counter, a Faraday Cup electrometer, a magnetic spectrometer, an omnidirectional spectrometer, a scintillation spectrometer, and a plasma wave detector.[2]

Also included as an engineering experiment on OV2-1 was a low-thrust, subliming solid rocket type, developed by Rocket Research Corporation in Seattle,[4] to manage OV2-1's rate of spin.[3]:422

Mission

In its original conception, OV2-1 was to have been launched via Titan 3A rocket to an apogee of 2,400 nmi (4,400 km) and a perigee of 100 nmi (190 km).[4] OV2-1 ultimately was launched on the second Titan IIIC test flight[3]:422 on October 15, 1965 at 17:23:59 UT from Cape Canaveral LC40[1] along with LCS-2, a 1.12 m (3.7 ft), 34 kg (75 lb) radar calibration sphere.[6] Once in orbit, the Titan IIIC's Transtage (upper stage) was scheduled to fire ten times, ultimately boosting OV2-1 into its operational orbit. 56 minutes and 10 seconds into the mission,[5] however, at the end of a 24-second burn, one of the two Transtage engines failed to shut down. The booster tumbled and then exploded,[3]:422 stranding the satellite amidst the debris in a nearly circular orbit about 750 km (470 mi) above the Earth.[2]

Legacy and status

The satellite and large pieces of the transtage are still in orbit as of February 2020, and LCS-2 reentered on August 25, 1982.[7]

Two follow-on satellites (OV2-2 and -3) with different mission objectives were originally planned when the OV2 program began.[4] The OV2 series was ultimately expanded to five satellites, all with different goals. Only one, the radiation and astronomical satellite OV2-5), achieved a degree of success.[8]

References

- McDowell, Jonathan. "Launch Log". Jonathan's Space Report. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- "OV2-1". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Powell, Joel W.; Richards, G.R. (1987). "The Orbiting Vehicle Series of Satellites". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. Vol. 40. London: British Interplanetary Society.

- "OV2-1A Readied for Titan 3 A Test". Aviation Week and Space Technology. New York: McGraw Hill Publishing Company. February 8, 1965. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- Hillger, Don; Toth, Garry. "OV". Collective Philatelic Works (of Two Meteorologists). Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- Krebs, Gunter. "LCS 1, 2, 3, 4". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- McDowell, Jonathan. "Satellite Catalog". Jonathan's Space Report. Retrieved February 11, 2020.

- Krebs, Gunter. "OV2". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

External links

- Current orbital information for OV2-1/LCS2. heavens-above.com