Northern crested caracara

The northern crested caracara (Caracara cheriway), also called the northern caracara and crested caracara,[3] is a bird of prey in the family Falconidae. It was formerly considered conspecific with the southern caracara (C. plancus) and the extinct Guadalupe caracara (C. lutosa) as the "crested caracara". It has also been known as Audubon's caracara. As with its relatives, the northern caracara was formerly placed in the genus Polyborus. Unlike the Falco falcons in the same family, the caracaras are not fast-flying aerial hunters, but are rather sluggish and often scavengers.

| Crested caracara | |

|---|---|

| |

| In the wild in Roma, Texas | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Falconiformes |

| Family: | Falconidae |

| Genus: | Caracara |

| Species: | C. cheriway |

| Binomial name | |

| Caracara cheriway (Jacquin, 1784) | |

| |

| Range of C. cheriway | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Polyborus cheriway | |

Distribution

The northern caracara is a resident in Cuba, northern South America (south to northern Peru and northern Amazonian Brazil) and most of Central America and Mexico, just reaching the southernmost parts of the United States, including Florida, where it has been seen on the East coast as far as extreme eastern Seminole County(Lake Harney), Florida where it is now considered a resident but listed as threatened. There have been reports of the northern caracara as far north as San Francisco, California.[4] and, in 2012, near Crescent City, California.[5] In July 2016 a northern caracara was reported and photographed by numerous people in the upper peninsula of Michigan, just outside of Munising.[6][7][8] In June 2017, a northern caracara was sighted far north in St. George, New Brunswick, Canada.[9] A specimen was photographed in Woodstock, Vermont in March 2020. The species has recently become more common in central and north Texas and is generally common in south Texas and south of the US border. It can also be found (nesting) in the Southern Caribbean (e.g. Aruba, Curaçao and Bonaire).

Description

The northern caracara has a length of 49 to 63 cm (19 to 25 in), a wingspan of 118 to 132 cm (46 to 52 in), and weighs 701 to 1,387 g (1.545 to 3.058 lb).[10][11][12][13] Average weight is considerably higher in the north of the range, smaller in the tropics. In Florida, 21 male birds averaged 1,117 g (2.463 lb) and 18 female birds averaged 1,200 g (2.6 lb). In Panama, males were found to average 834 g (1.839 lb) and females averaged 953 g (2.101 lb).[14] Among caracaras, it is second in size only to the southern caracara.[15] Broad-winged and long-tailed, it also has long legs and frequently walks and runs on the ground. It is very cross-shaped in flight. The adult has a black body, wings, crest and crown. The neck, rump, and conspicuous wing patches are white, and the tail is white with black barring and a broad terminal band. The breast is white, finely barred with black. The bill is thick, grey and hooked, and the legs are yellow. The cere and facial skin are deep yellow to orange-red depending on age and mood. Sexes are similar, but immature birds are browner, have a buff neck and throat, a pale breast streaked/mottled with brown, greyish-white legs and greyish or dull pinkish-purple facial skin and cere. The voice of this species is a low rattle.

Adults can be separated from the similar southern caracara by their less extensive and more spotty barring to the chest, more uniform blackish scapulars (brownish and often lightly mottled/barred in the southern), and blackish lower back (pale with dark barring in the southern). Individuals showing intermediate features are known from the small area of contact in north-central Brazil, but intergradation between the two species is generally limited.

Habitat

Northern caracaras inhabit various types of open and semi-open country. They typically live in lowlands but can live to mid-elevation in the northern Andes. The species is most common in cattle ranches with scattered trees, shelterbelts and small woods, as long as there is a somewhat limited human presence. They can also be found in other varieties of agricultural land, as well as prairies, coastal woodlands (including mangroves), coconuts plantations, scrub along beach dunes and open uplands.

Behavior

The northern caracara is a carnivorous scavenger that mainly feeds on carrion, but does occasionally eat fruit. The live prey they do catch is usually immobile, injured, incapacitated or young. Prey species can include small mammals, amphibians, reptiles, fish, crabs, insects, their larvae, earthworms, shellfish and young birds. Bird species that are culled can range from large, colonial nesting birds such as storks and herons to small passerines. Reptiles taken often including snakes, lizards and small freshwater turtles as well as young American alligators.[11] This species, along with other caracaras, is one of few raptors that hunts on foot, often turning over branches and cow dung to reach food. In addition to hunting its own food on the ground, the northern caracara will steal from other birds, including vultures, buteos, pelicans, ibises and spoonbills. Because they stay low to the ground even when flying, they often beat Cathartes vultures to carrion and can aggressively displace single vultures of most species from small carcasses. They also dominate crows at carrion sites but are subordinate to the much larger bald eagle.[16] They will occasionally follow trains or automobiles to fetch food that falls off.[15] An unexceptedly large volume of insects and spiders can be found in the diet in the southern United States.[17][18] In Florida, it was estimated that about 33% of vertebrate prey was obtained as carrion, which indicated that hunting groups may be capable of dispatching unusually large live prey, including Virginia opossum and skunks.[19] Adults of various water birds up to the size of egrets, grebes and even American white ibis are sometimes also killed by caracaras.[20][21]

Northern caracaras can usually be spotted either alone, in pairs or family parties of 3–5 birds. Occasionally roosts may contain more than a dozen caracaras and abundant food sources can cause more than 75 to gather. The nesting season is from December to May and is a bit earlier the closer the birds live to the tropics. They build large stick nests in trees such as mesquites and palms, cacti, or on the ground as a last resort.[22] The nests are bulky and untidy, 60–100 cm (24–39 in) wide and 15–40 cm (5.9–15.7 in) deep, often made of grasses, sticks and hay, spotted with much animal matter.[15] It lays 2 to 3 (rarely 1 to 4) pinkish-brown eggs with darker blotches, which are incubated for 28–32 days.[23] Although mesopredators such as raccoons and fish crows may steal eggs and nestlings from nests in Florida, adults may have no known natural predators.[21] Red imported fire ants are another known predator of nestling crested caracaras.[24]

Taxonomy

Though the northern caracaras of our time are not divided into subspecies as their variation is clinal, prehistoric subspecies are known. Due to the confused taxonomic history of the crested caracaras, their relationships to the modern birds are in need of restudy:

- Caracara cheriway grinnelli (La Brea caracara: Late Pleistocene of California)

- Caracara cheriway prelutosus (Late Pleistocene of Mexico)

The former almost certainly represents birds which were the direct ancestors of the living population. The latter may actually be the ancestor of the Guadalupe caracara.

A DNA analysis of 2,500 year old bones of the recently extinct Bahaman caracara, shows that the species was closely related to the northern crested caracara and the southern crested caracara. The three species having last shared a common ancestor between 1.2 and 0.4 million years ago.[25]

Florida caracara

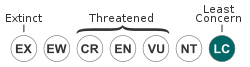

The state of Florida is home to a relict population of northern caracaras that dates to the last glacial period, which ended around 12,500 BP. At that point in time, Florida and the rest of the Gulf Coast was covered in an oak savanna. As temperatures increased, the savanna between Florida and Texas disappeared.[26] Caracaras were able to survive in the prairies of central Florida as well as in the marshes along the St. Johns River. Cabbage palmettos are a preferred nesting site, although they will also nest in southern live oaks.[27] Their historical range on the modern-day Florida peninsula included Okeechobee, Osceola, Highlands, Glades, Polk, Indian River, St. Lucie, Hardee, DeSoto, Brevard, Collier, and Martin counties.[28] They are currently most common in DeSoto, Glades, Hendry, Highlands, Okeechobee and Osceola counties.[29] Loss of adequate habitat caused the Florida caracara population to decline, and it was listed as threatened by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service in 1987.[28]

Northern caracara in Mexico

The Mexican ornithologist Rafael Martín del Campo proposed that the northern caracara was probably the sacred "eagle" depicted in several pre-Columbian Aztec codices as well as the Florentine Codex. This imagery was adopted as a national symbol of Mexico, and is seen on the flag among other places. Since the paintings were interpreted as showing the golden eagle, it became the national bird.[30]

Texan eagle

Balduin Möllhausen, the German artist accompanying the 1853 railroad survey, led by Lt. Amiel Weeks Whipple, from the Canadian River to California along the 35th parallel, recounted observing what he called the "Texan Eagle," which, in his account, he identified as Audubon's Polyborus vulgaris. This sighting occurred in the San Bois Mountains in southeastern Oklahoma.[31]

Gallery

Young adult perched on a cactus, Bonaire, BES Islands

Young adult perched on a cactus, Bonaire, BES Islands%2C_Attwater_Prairie_Chicken_National_Wildlife_Refuge%2C_Colorado_County%2C_Texas%2C_USA_(24_May_2014).jpg) Northern crested caracara (Caracara cheriway), Attwater Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge, Colorado County, Texas, USA (24 May 2014)

Northern crested caracara (Caracara cheriway), Attwater Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge, Colorado County, Texas, USA (24 May 2014) An immature bird surveying the surroundings in Texas, USA

An immature bird surveying the surroundings in Texas, USA

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Caracara cheriway". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dove, Carla J.; Banks, Richard C. (1999). "A Taxonomic Study of Crested Caracaras (Falconidae)" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. 111 (3): 330–339.

- "Common Names for Crested Caracara (Caracara cheriway)". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- "Rare Raptors". Golden Gate Raptor Observatory. Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- "caracara sighting record". Project Noah. 13 February 2012.

- Scot, Stewart. "News". Nature Photography by Scot Stewart. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- Bernard, Daryl. "Crested Caracara". iNaturalist.org. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- "Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore Instagram". Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- Corbett, Tanya. "News". CBC News. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- "Crested Caracara". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- Morrison, J. L. and J. F. Dwyer (2020). Crested Caracara (Caracara cheriway), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

- Peterson, R. T., & Peterson, V. M. (Eds.). (2002). Peterson Field Guide to the Birds of Eastern and Central North America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Clark, W. S., & Schmitt, N. J. (2017). Raptors of Mexico and Central America. Princeton University Press.

- CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses, 2nd Edition by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (2008), ISBN 978-1-4200-6444-5.

- Ferguson-Lees, James; Christie, David A. (2001). Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-618-12762-3.

- Dwyer, J. F. (2014). Correlation of cere color with intra-and interspecific agonistic interactions of Crested Caracaras. Journal of Raptor Research, 48(3), 240-247.

- Morrison, J. L., Pias, K. E., Abrams, J., Gottlieb, I. G., Deyrup, M., & McMillian, M. (2008). Invertebrate diet of breeding and nonbreeding Crested Caracaras (Caracara cheriway) in Florida. Journal of Raptor Research, 42(1), 38-47.

- Morrison, J. L., Abrams, J., Deyrup, M., Eisner, T., & McMillian, M. (2007). Noxious menu: Chemically protected insects in the diet of Caracara cheriway (Northern Crested Caracara). Southeastern Naturalist, 6(1), 1-14.

- Morrison, J. L., & Pias, K. E. (2006). Assessing the vertebrate component of the diet of Florida's crested caracaras (Caracara cheriway). Florida Scientist, 36-43.

- Pérez-Estrada, C. J., & Rodríguez-Estrella, R. (2016). Caracara cheriway predation on migratory waterbirds, Egretta thula and Podiceps nigricollis, in southern Baja California Peninsula. Acta Zoológica Mexicana (nueva serie), 32(1), 129-131.

- Layne, J. N. (1996). Audubon's Crested Caracara. In Rare and endangered biota of Florida. Vol. V: Birds., edited by Jr J. A. Rogers, H. W. Kale Ii and H. T. Smith, 197-210. Gainesville: Univ. of Florida Press.

- "Northern Caracara". Salt Grass Flats. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- "Crested Caracara (Polyborus plancus)". Explore Birds of Prey. The Peregrine Fund. Archived from the original on 29 August 2009. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- Dickinson, V. M. (1995). Red imported fire ant predation on Crested Caracara nestlings in south Texas. Wilson Bulletin 107:761-762.

- "Extinct Caribbean bird yields DNA after 2,500 years in watery grave". phys.org. Retrieved 2019-08-20.

- "Chapter VIII. Florida Relict Species". Resource Guide. Indian River Lagoon Envirothon. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- "Audubon's Crested Caracara" (PDF). South Florida Ecological Services Office. United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- Morrison, J.L. (October 2004). "The Crested Caracara in the changing grasslands of Florida" (PDF). In Noss, R. (ed.). Land of Fire and Water: The Florida Dry Prairie Ecosystem. Proceedings of the Florida Dry Prairie Conference, October 2004. Sebring, Florida. pp. 211–215.

- "Species Profile: Crested Caracara". Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- González Block, Miguel A. (2004). "El Iztaccuahtli y el Águila Mexicana: ¿Cuauhtli o Águila Real?". Arqueología Mexicana (in Spanish). XII (70): 60–65. Archived from the original on 2009-02-16.

- Möllhausen, Balduin (1858). Diary of a Journey from the Mississippi to Coasts of the Pacific With a United States Government Expedition. Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, & Roberts. p. 45.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caracara cheriway. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Caracara cheriway |

- eNature.com page with photograph and sound

- National Birds: Mexico

- "Crested caracara media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Crested caracara photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Crested caracara species account at Neotropical Birds (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)