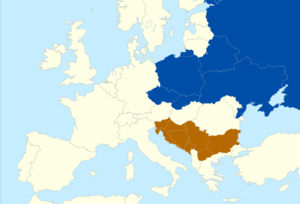

North Slavs

The North Slavs are a subgroup of Slavic peoples who speak the North Slavonic languages,[1][2] a classification which is not universally accepted although it has been in use for several centuries.[3][4][5][6] They separated from the common Slavic group in the 7th century CE, and established independent polities in Central and Eastern Europe by the 8th and 9th centuries.[7]

North Slavic countries

South Slavic countries | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 265+ million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Majority: Central and Eastern Europe, North Asia Minority: Western Europe and Northern America | |

| Languages | |

| North Slavic (West Slavic and East Slavic) tongues: Belarusian, Czech, Kashubian, Polish, Russian, Rusyn, Silesian, Slovak, Sorbian, Ukrainian | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Protestantism, Lutheranism, Irreligious Minorities | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Slavs (namely South Slavs) |

North Slavic peoples today include the Belarusians, Czechs, Kashubians, Poles, Silesians, Rusyns, Russians, Slovaks, Sorbs, and Ukrainians.[2][6] They inhabit a contiguous area in Central and Eastern Europe stretching from the north of the Baltic Sea to the Sudetes and the Carpathian Mountains in the south (historically also across the Eastern Alps into the Apennine peninsula and the Balkan peninsula); from the west in the Czech Republic to the east in the Russian Federation.[7] There is also a significant share of North Slavic population in North Asia (Eastern Russia), and significant diaspora groups throughout the rest of the world.[8]

North Slavs vs West/East Slavs

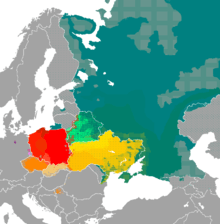

Although the use of the East and West Slavonic categories the standard model, some theorists claim that these two groups share enough of the same or similar linguistic and cultural characteristics to be classed together as one North Slavic branch.[1][2][9][10] The crux of this argument is that there is a northern ethos and a southern ethos of the Slavs (a North Slavic and a South Slavic dialect continuum, a Northeastern European and a Southeastern European cuisine, etc.).[11] This split was caused by migrations of Slavonic tribes and reinforced by the Hungarian invasions of Europe at the end of the first millennium CE, causing the Slavic societies to gradually grow into two separate cultures.[7] The term "North Slav" itself has been used in academic works as early as 1841[12][3][13] and the concept continued to appear in publications in the centuries that followed.[4] A publication from 1938 noted that "the north Slavs have a little lighter hair and skin color than the south Slavs; and far to the north they have much lighter hair".[14]

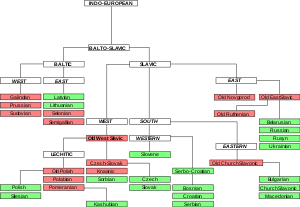

In terms of language, the greatest contrasts are evident between South Slavic tongues and the rest of the family.[1][2][15] Moreover, there are many exceptions and whole dialects that break the division of East and West Slavic languages. Thus the Slavs are clearly divided into two main linguistic groups: the North Slavs and the South Slavs, which can then be further categorised as the Northwest tongues (Czech, Kashubian, Polish, Silesian, Slovak, and Sorbian) and the Northeast ones (Belarusian, Russian, Rusyn, and Ukrainian) – whereas the Southern branch is split into the widely accepted groups of the Southwest languages (Serbo-Croatian and Slovene) and the Southeast tongues (Bulgarian and Macedonian). This model is argued as being more appropriate than the triple dissection of east, west and south.[1]

North Slavic cuisine features some Central European and some Near Eastern influences.[11] The South Slavs have a considerably more Mediterranean gastronomy because of the difference in climate and close proximity of Italy and Greece. Due to centuries of interaction with the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires, Byzantine and Ottoman cultural influences in the region of South Slavs are significant.[16] There is a cultural split of the North Slavonic family into two separate categories according to religion: the West Slavic languages are of mostly Catholic countries and the East Slavic languages are of primarily Orthodox territories.[1]

A 1922 article in The Living Age defined the term "Norths Slavs" differently:[17] it featured a triple grouping where the South Slavic branch remains the same but the North Slavs include only the Czechs, Slovaks, and Poles; the Russians and Ukrainians instead were categorised separately as East Slavs according to this definition.[17]

Population

There are an estimated 265,000,000 North Slavs worldwide.

| Nation | State | Numbers |

|---|---|---|

| Russians | 130,000,000[18][19] | |

| Poles | 57,393,000[20] | |

| Ukrainians | 46,700,000[21] | |

| Czechs | 12,000,000[22] | |

| Belarusians | 10,000,000[23] | |

| Slovaks | 6,940,000[24] | |

| Silesians | 2,000,000[25] | |

| Rusyns | 92,000[26] | |

| Sorbs | 70,000[27] | |

| Kashubians | 5,000[28][29] |

Significant minorities of North Slavic populations exist in Western Europe (primarily Germany, the United Kingdom, and Ireland) as well as Northern America (mostly the United States and Canada. The oceanside neighbourhood of Brighton Beach in New York City's Brooklyn borough is known for its high Russian-speaking population; likewise, Chicago is home to a large number of Polish Americans and Polish immigrants. Chicago is also the city with the third largest Czech population, after Prague and Vienna.[30][31] Since the 2004 enlargement of the European Union, Germany and the UK have gathered considerable amounts of migrant Poles. In England, Polish has become the second most spoken native language after English – with over 500,000 speakers, according to the 2011 census.[32] In Ireland, over 120,000 Poles make up the largest minority in the country according to 2016 figures.[33] Polish food can be found in Eastern European shops across various parts of the British Isles.[34] Lusatia, mostly in Germany, is the original homeland of the Sorbs living there who speak the Sorbian languages; since they did not migrate there and are native to this territory, they are also known as the "Lusatian Sorbs". They are the only descendants of the Polabian Slavs to have retained their identity and culture over centuries of living under Germanic rule.

Languages

The North Slavonic tongues today are:

- Northwest branch

- Northeast branch

Much overlap can be found between the Northwest and Northeast branches. Ukrainian and Belarusian have both been hugely influenced by Polish in the past centuries due to their geographic and cultural proximity, as well as to the Polonization of the Ruthenian population of the Polish Commonwealth.[11]

According to Kostiantyn Tyshchenko, Ukrainian shares 70% common vocabulary with Polish, 66% with Slovak, and 62% with Russian.[35] Furthermore, Tyschenko identified 82 grammatical and phonetic features of the Ukrainian tongue – Polish, Czech and Slovak share upwards of 20 of these characteristics with Ukrainian, and 11 are shared with Russian.[36]

A number of now extinct tongues once existed within these groups, such as Slovincian in the Lekhitic subgroup or the Old Novgorod dialect within the Northeast section.

In contrast to other dialects of Slovak, Eastern dialects (so-called Slovjak) are less intelligible with Czech and more with Polish and Rusyn.[37]

History

The first written use of the name "Slavs" dates to the 6th century, when the Slavic tribes inhabited a large portion of Central and Eastern Europe. By that century, native Iranian ethnic groups (the Scythians, Sarmatians, and Alans) had been absorbed by the region's Slavic population.[38][39][40][41] Over the next two centuries, the Slavs expanded southwest toward the Balkans and the Alps and northeast towards the Volga River.[42]

Beginning in the ninth century, the Slavs gradually converted to Christianity (both Byzantine Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism) – beginning with the southern regions and ending at the eastern reaches.[43] By the 12th century, they were the core population of a number of medieval Christian states: the Northwest Slavs in Poland, the Holy Roman Empire (Pomerania, Bohemia, Moravia), Kingdom of Hungary (Nitria), and the Northeast Slavs in Kievan Rus'. During the Late Middle Ages, the main polities of the North Slavs were the Kingdom of Bohemia, Kingdom of Poland, Duchy of Masovia, Grand Duchy of Moscow, the Pskov Republic, and the Novgorod Republic. Lands of the former Kievan Rus' had become fragmented due to the Mongol invasion of the 13th century and would remain so until the first half of the 16th century.

In the early modern period, two major European powers – the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Tsardom of Russia – had large populations that consisted primarily of North Slavonic nations and North Slavic language speakers (primarily Poles, Ruthenians, Russians, Cossacks). Polish and Russian became the lingua franca of wide stretches of Catholic and Orthodox lands in Eastern Europe respectively.[44][45][46][47] Politically, Russia has dominated the region beginning with the fall of the Polish Kingdom in 1795. The Russian Empire continued to rule almost all of Eastern Europe and parts of Central Europe for the entirety of the 19th century up until the outbreak of World War I, which resulted in the overthrow of the tsarist autocracy during the October Revolution. The success of the USSR and establishment of the Eastern Bloc followed.

While the Czech lands have never been as much of a military or political power during the region's history as Poland and Russia have, it was arguably seen by some as one of the most cultured of the North Slavic lands and the first to accept their new religion.[43] The Czechs were the first in the east to be Christianised in the 9th century, they later became arguably the most religiously tolerant of the Slavonic nation-states thanks to the Bohemian Reformation. However today, the Czech Republic is one of the most irreligious countries in the world.[48] Presently, after the fall of the Eastern Bloc, North Slavonic nation-states are split among two different factions: the NATO and EU members of the Visegrád Group (the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovakia) and the Commonwealth of Independent States (Belarus and Russia). Ukraine is currently a partner of both the CIS and NATO, while also taking part in the EU's Eastern Partnership initiative as part of the European Neighbourhood Policy.

Religion

In the present day, Christianity dominates among the North Slavic peoples, with Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism being the most popular denominations. In 2011, 48.3% of Belarusians living in their home country declared themselves as Orthodox.[49] A 2012 study in Russia placed the number of Orthodox Russians at 41%,[50][51] whereas a 2016 survey tells us that 65.4% of Ukrainians share these beliefs.[52] 87.5% of Poland's population declared Roman Catholic faith.[53][54][55] 65% of Polish believers attend church services on a regular basis.[56] 62% of Slovakia's inhabitants are Catholic.[57] Among Czechs, 34.5% claim to have no religion, 44.7% undeclared, and only 10.5% Roman Catholics.[58][59][60]

See also

References

- Živković, Tibor; Crnčević, Dejan; Bulić, Dejan; Petrović, Vladeta; Cvijanović, Irena; Radovanović, Bojana (2013). The World of the Slavs: Studies of the East, West and South Slavs: Civitas, Oppidas, Villas and Archeological Evidence (7th to 11th Centuries AD). Belgrade: Istorijski institut. ISBN 8677431047.

- Kamusella, Tomasz; Nomachi, Motoki; Gibson, Catherine (2016). The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137348395.

- The Phrenological Journal and Science of Health: Incorporated with the Phrenological Magazine, Volumes 68-69. New York: Fowler & Wells. 1879. p. 99.

- Psychological Bulletin, Volume 3. American Psychological Association. 1906. p. 419.

- The Survey, Volume 13. Survey Associates. 1905. pp. 201–203.

- Social Studies for Minnesota Schools, Seventh Year. C. Scribner's Sons. 1933. p. 44.

- Lunt, Horace G. (2001). Old Church Slavonic Grammar. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 183. ISBN 3110162849.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (18 September 2006). "Slav (people) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- Grimm, Jacob (2012). Teutonic Mythology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1108047041.

- Bloch, Iwan (2001). Anthropological Studies on the Strange Sexual Practices of All Races and All Ages. Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific. p. 31. ISBN 0898754712.

- Serafin, Mikołaj (January 2015). "Cultural Proximity of the Slavic Nations" (PDF). Retrieved April 28, 2017.

- The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders. New York: Springer. 2016. p. 239.

- Horne, Charles Francis (1870–1942). The World and its People: Or, a Comprehensive Tour of All Lands, Volume 4. ReInk Books.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Ruggd, Harold Ordway (1938). Our Country and Our People: An Introduction to American Civilization, Revised. Ginn. p. 157.

- Lindsay, Robert. "Mutual Intelligibility of Languages in the Slavic Family" (docx). Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- Globus-Skopje (February 8, 2010). "Can't take the Ottoman out of the Balkans". Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- The Living Age, Volume 313. Living Age Company. 1922. pp. 194–195, 199.

- "Нас 150 миллионов -Русское зарубежье, российские соотечественники, русские за границей, русские за рубежом, соотечественники, русскоязычное население, русские общины, диаспора, эмиграция". Russkie.org. 20 February 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- including 36,522,000 single ethnic identity, 871,000 multiple ethnic identity (especially 431,000 Polish and Silesian, 216,000 Polish and Kashubian and 224,000 Polish and another identity) in Poland (according to the census 2011) and estimated 20,000,000 out of Poland Świat Polonii, witryna Stowarzyszenia Wspólnota Polska: "Polacy za granicą" (Polish people abroad as per summary by Świat Polonii, internet portal of the Polish Association Wspólnota Polska)

- Paul R. Magocsi (2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. University of Toronto Press. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-1-4426-1021-7.

- "Tab. 6.2 Obyvatelstvo podle národnosti podle krajů" [Table. 6.2 Population by nationality, by region] (PDF). Czech Statistical Office (in Czech). 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2012.

- Karatnycky, Adrian (2001). Freedom in the World: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties, 2000–2001. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-7658-0884-4. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- including 4,353,000 in Slovakia (according to the census 2011), 147,000 single ethnic identity, 19,000 multiple ethnic identity (especially 18,000 Czech and Slovak and 1,000 Slovak and another identity) in Czech Republic (according to the census 2011), 53,000 in Serbia (according to the census 2011), 762,000 in the USA (according to the census 2010 Archived 2020-02-12 at Archive.today), 2,000 single ethnic identity and 1,000 multiple ethnic identity Slovak and Polish in Poland (according to the census 2011), 21,000 single ethnic identity, 43,000 multiple ethnic identity in Canada (according to the census 2006)

- "The Institute for European Studies, Ethnological institute of UW" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-08-16.

- Paul Magocsi (1995). "The Rusyn Question". Political Thought. 2–3 (6).

- "Sorbs of East Germany". faqs.org. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "The Institute for European Studies, Ethnological institute of UW" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-08-16.

- "Kaschuben heute: Kultur-Sprache-Identität" (PDF) (in German). pp. 8–9. Retrieved 2016-01-03.

- Cozine, Alicia (2005). "Czechs and Bohemians". The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- Czech and Slovak roots in Vienna Archived 2014-05-12 at the Wayback Machine, wieninternational.at

- QS204EW – Main language, ONS 2011 Census. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- Census 2016 Archived April 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Polski sklep w Newcastle News article about a Polish shop in the North East of England.(in Polish)

- Tyschenko, Kostiantyn. "Мови Європи: відстані між мовами за словниковим складом". Archived from the original on May 1, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2017.

- Tyshchenko, K. (2012). Правда про походження української мови. In: Lytvynenko, S (ed.) Український тиждень, Iss. 39, p. 35.

- Štolc, Jozef (1994). Slovenská dialektológia [Slovak dialectology]. Bratislava: Veda.: Ed. I. Ripka.

- Brzezinski, Richard; Mielczarek, Mariusz (2002). The Sarmatians, 600 BC-AD 450. Osprey Publishing. p. 39.

[...] Indeed, it is now accepted that the Sarmatians merged in with pre-Slavic populations.

- Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 523.

[...] In their Ukrainian and Polish homeland the Slavs were intermixed and at times overlain by Germanic speakers (the Goths) and by Iranian speakers (Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans) in a shifting array of tribal and national configurations.

- Atkinson, Dorothy; Dallin, Alexander; Warshofsky Lapidus, Gail, eds. (1977). Women in Russia. Stanford University Press. p. 3.

[...] Ancient accounts link the Amazons with the Scythians and the Sarmatians, who successively dominated the south of Russia for a millennium extending back to the seventh century B.C. The descendants of these peoples were absorbed by the Slavs who came to be known as Russians.

- Slovene Studies. 9–11. Society for Slovene Studies. 1987. p. 36.

[...] For example, the ancient Scythians, Sarmatians (amongst others), and many other attested but now extinct peoples were assimilated in the course of history by Proto-Slavs.

- "[B]etween the sixth and seventh centuries, large parts of Europe came to be controlled by Slavs, a process less understood and documented than that of the Germanic ethnogenesis in the west. Yet the effects of Slavicization were far more profound". Geary (2003, p. 144)

- Grimm, Jacob (2012). Teutonic Mythology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 1108047041.

- Nataliia Polonska-Vasylenko, History of Ukraine, "Lybid", (1993), ISBN 5-325-00425-5, v.I, Section: "Ukraine under Poland."

- Natalia Iakovenko, Narys istorii Ukrainy s zaidavnishyh chasic do kincia XVIII stolittia, Kiev, 1997, Section: 'Ukraine-Rus.'

- Polonska-Vasylenko, Section: "Evolution of Ukrainian lands in the 15th–16th centuries."

- Thomas Lane. Lithuania stepping westwards. Routledge, 2001. p. 24.

- GALLUP WorldView

- "Religion and denominations in the Republic of Belarus" (PDF). Mfa.gov.by. November 2011. Retrieved 2017-01-10.

- "Arena: Atlas of Religions and Nationalities in Russia". Sreda, 2012.

- 2012 Arena Atlas Religion Maps. "Ogonek", № 34 (5243), 27/08/2012. Retrieved 21/04/2017. Archived.

- Релігія, Церква, суспільство і держава: два роки після Майдану [Religion, Church, Society and State: Two Years after Maidan] (PDF) (in Ukrainian), Kiev: Razumkov Center in collaboration with the All-Ukrainian Council of Churches, 26 May 2016, pp. 22, 27, 29, 31, archived from the original (pdf) on 22 April 2017, retrieved 10 May 2017

Sample of 2,018 respondents aged 18 years and over, interviewed 25-30 March 2016 in all regions of Ukraine except Crimea and the occupied territories of the Donetsk and Lugansk regions. - GUS, Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludnosci 2011: 4.4. Przynależność wyznaniowa (National Survey 2011: 4.4 Membership in faith communities) p. 99/337 (PDF file, direct download 3.3 MB). ISBN 978-83-7027-521-1 Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny (2012). Rocznik statystyczny Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej 2012 (PDF) (in Polish and English). Warszawa: Zakład Wydawnictw Statystycznych.

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny (2013-03-28). "Wyznania religijne stowarzyszenia narodowościowe i etniczne w Polsce 2009–2011" (PDF) (in Polish and English). Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- http://wiadomosci.gazeta.pl/wiadomosci/1,114871,17506668,CBOS__56_proc__Polakow_nie_ma_watpliwosci__ze_Bog.html?lokale=local#BoxNewsLink

- "Table 14 Population by religion" (PDF). Statistical Office of the SR. 2011. Retrieved Jun 8, 2012.

- "Úvodní stránka - SLDB 2011". czso.cz. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- "Population by religious belief and by municipality size groups" (PDF). Czech Statistical Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- "Population by religious belief by regions" (PDF). Czech Statistical Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2012.