Nisaba

Nisaba (Sumerian: 𒀭𒉀 DNAGA; later 𒀭𒊺𒉀 DŠE.NAGA),[1] is the Sumerian goddess of writing, learning, and the harvest. She was worshiped in shrines and sanctuaries at Umma and Ereš, and was often praised by Sumerian scribes. She is considered the patroness of mortal scribes as well as the scribe of the gods. In the Babylonian period, her worship was mainly redirected towards the god Nabu, who took over her functions.

| Nisaba | |

|---|---|

Goddess of grain, accounting, and writing | |

| |

| Symbol | Stalk of wheat, gold stylus, starry tablet |

| Parents | Anu and Urash (Umma and Ereš tradition) Enlil and Ninlil (Lagash tradition) |

| Consort | Ḫaya |

| Equivalents | |

| Babylonian equivalent | Nabu |

| Egyptian equivalent | Seshat |

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

|---|

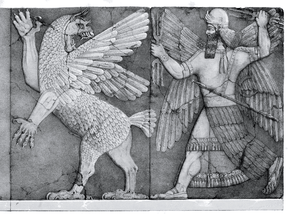

Chaos Monster and Sun God |

|

Seven gods who decree

|

|

Other major deities |

|

Demigods and heroes

|

| Related topics |

Name

Nisaba's name was originally written using a combination of the cuneiform sign 𒉀, called NAGA, and the dingir, 𒀭, representing divinity. The NAGA sign is a pictogram representing a stalk of wheat, denoting her as the divinity present within grains.[2] Although the sign NAGA is sometimes read as Nidaba, Jeremy Black points out that "the name Nisaba (or Nissaba) seems more correct than Nidaba".[2] She is also known by the epithet Nanibgal (Sumerian: 𒀭𒉀 DAN.NAGA; later 𒀭𒊺𒉀 DAN.ŠE.NAGA),[1] and may have been the same goddess as Nunbarsegunu.[3]

Iconography and worship

Nisaba's worship began in the city of Umma, where she was originally a grain goddess during Early Dynastic Period I, c. 2900–2700 BC.[2] As a grain goddess, she was represented by the symbol of a single stalk of grain.[2] A fragment from a stone vase, probably found in Girsu and held in the British Museum, shows a goddess usually identified as Nisaba (though it could depict Baba or Inanna). She is depicted with four long curled tresses of hair crowned with a horned headdress supporting ears of wheat and a crescent moon, and holds a bunch of dates.[4] After she became recognized as a goddess of writing, she was described on the Gudea cylinders (c. 2125 BC) as holding a gold stylus and a clay tablet carrying the image of starry heaven.[2][5]

Nisaba's transition from being strictly a grain goddess to one also worshiped as patroness of writing and accounting probably took place as modes of writing became more and more important for documenting the buying and selling of grain and other staple goods. Cuneiform writing itself was seen as a gift handed down from the goddess.[6] As writing itself moved from a simple accounting shorthand to documenting contracts, laws, history, and literature, Nisaba's worship grew to include these functions.[2] Her worship spread to Ereš, which housed a shrine to her and other deities in the temple, though she does not seem to have had any temples dedicated solely to her worship. Worship seems to have been conducted primarily via the art of writing, and each composition was seen as a gift for the goddess.[2] Many clay-tablets end with the phrase “Nisaba be praised” (Sumerian: 𒀭𒉀𒍠𒊩 AN.NAGA.ZAG.SAL; Dnisaba za3-mi2)[1] to honor her. A Hymn to Nisaba composed during the Second Dynasty of Ur begins, "Lady colored like the stars of heaven, holding a lapis lazuli tablet! Nisaba, great wild cow born of Uras, wild sheep nourished on good milk among holy alkaline plants, opening the mouth for seven reeds! Perfectly endowed with fifty great divine powers, my lady, most powerful."[2][7]

Nisaba's worship seems to have declined during the Babylonian period and the reign of Hammurabi in the 18th century BC, during which time goddesses were de-emphasized in favor of gods. By end of the Third Dynasty of Ur, her worship seems to have been mostly replaced by that of Nabu, the male god of writing, who in some sources had Nisaba as his wife, though she continued to be revered alongside him in his temples for millennia. She continued to be counted alongside Nabu in lists of the gods of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and their widespread veneration protected them from some of the religious persecution that came with new regimes. However, while the cult of Nabu spread as far as the Mediterranean during the first few centuries AD, worship of Nisaba seems to have remained within Mesopotamia, where it seems to have died out following the fall of the Seleucid Empire in 63 BC, the last period during which she is attested in historical records. This saw Nisaba fall into obscurity and lose influence, her remaining forms of worship likely being suppressed as Christianity spread.[2]

Mythology

Role

Nisaba serves as the scribe of the gods in Sumerian and later Mesopotamian mythology. The god of wisdom, Enki, who organized the world after creation, gave each deity a role in the world order. He named Nisaba the scribe of the gods, and Enki then built her a school of learning so that she could better serve those in need. She keeps records, chronicles events, and performs various other bookwork-related duties for the gods. She is also in charge of marking regional borders. Some pieces of writing, such as the Kesh Temple Hymn (one of the oldest surviving pieces of literature in the world[8]), were said to have been spoken by the gods and recorded by Nisaba herself.[9]

She is the chief scribe of Nanshe. On the first day of the new year, she and Nanshe work together to settle disputes between mortals and give aid to those in need. Nisaba keeps a record of the visitors seeking aid and then arranges them into a line to stand before Nanshe, who will then judge them. Nisaba is also seen as a caretaker for Ninhursag's temple at Kesh, where she gives commands and keeps temple records.

Family

As with many Sumerian deities, Nisaba's exact place in the pantheon and her heritage appears somewhat ambiguous. In the tradition of her original center of worship at Umma, she is held to be the daughter of An and Urash,[10] and the sister of Ninsun, the mother of Gilgamesh. In the Eresh tradition, she is said to be the daughter of Enlil and Ninlil.[2] In still other sources, she is considered the mother of Ninlil, and by extension, the mother-in-law of Enlil.

Sources beginning in the First Babylonian dynasty (c. 1830 BC – c. 1531 BC) assign Nisaba a husband, named Ḫaya, who is described primarily as a god of scribes, though Ḫaya seems to have originally been little more than a masculine "reflection" of Nisaba.[11] In one of the Mesopotamian god lists, Ḫaya is called "the Nissaba of Wealth", counterpart to the female "Nissaba of Wisdom".[12] His rise to prominence following the end of the Third Dynasty of Ur[13] which marked the end of the Sumerian period and the beginning of the Babylonian period, around the same time as Nabu, came during a time period when many goddesses' roles were being re-ascribed to gods.[2]

| An | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ninḫursaĝ | Enki born to Namma | Ninkikurga born to Namma | Nisaba born to Uraš | Ḫaya | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ninsar | Ninlil | Enlil | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ninkurra | Ningal maybe daughter of Enlil | Nanna | Nergal maybe son of Enki | Ninurta maybe born to Ninḫursaĝ | Baba born to Uraš | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uttu | Inanna possibly also the daughter of Enki, of Enlil, or of An | Dumuzid maybe son of Enki | Utu | Ninkigal married Nergal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Meškiaĝĝašer | Lugalbanda | Ninsumun | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Enmerkar | Gilgāmeš | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Urnungal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Unicode for the cuneiform sign NAGA

Unicode 5.0 encodes the NAGA sign at U+12240 𒉀 (Borger 2003 nr. 293). AN.NAGA is read as NANIBGAL, and AN.ŠE.NAGA as NÁNIBGAL. NAGA is read as NÍDABA or NÍSABA, and ŠE.NAGA as NIDABA or NISABA.

The inverted (turned upside down) variant is at U+12241 𒉁 (TEME), and the combination of these, that is the calligraphic arrangement NAGA-(inverted NAGA), read as DALḪAMUN7 "whirlwind", at U+12243 𒉃. DALḪAMUN5 is the arrangement AN.NAGA-(inverted AN.NAGA), and DALḪAMUN4 is the arrangement of four instances of AN.NAGA in the shape of a cross.

See also

Further reading

- Uhlig, Helmut: Die Sumerer. Ein Volk am Anfang der Geschichte. (1992, 2002). Bastei Lübbe, ISBN 3-404-64117-5.

References

- Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses – Nidaba (goddess)

- Mark, Joshua J. "Nisaba", Ancient History Encyclopedia. 23 January 2017. Accessed online at https://www.ancient.eu/Nisaba/

- Monaghan, Patricia. 2010. Goddesses in World Culture, ABC-CLIO.

- Maxwell-Hyslop, K. (1992). The Goddess Nanše an Attempt to Identify Her Representation. Iraq, 54, 79-82. doi:10.2307/4200355

- Kramer, S.N. 1971. The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press.

- Shlain, L. (1999). The Alphabet Versus the Goddess: The conflict between word and image. Penguin.

- Black, Literature, 293

- Jeremy A. Black; Jeremy Black; Graham Cunningham; Eleanor Robson (13 April 2006). The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press. pp. 325–. ISBN 978-0-19-929633-0. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- Alster, B. (1976). On the Earliest Sumerian Literary Tradition. Journal of Cuneiform Studies, 28(2), 109-126. doi:10.2307/1359501

- From Sumerian texts, the language used to describe Urash is very similar to the language used to describe Ninhursag. Therefore, the two goddess may be one and the same. If Urash and Ninhursag are the same goddess, then Nisaba is also the half sister of Nanshe and (in some versions) Ninurta.

- Glassman, R. M. (2017). The Status and Role of Women in Ancient Sumer. In The Origins of Democracy in Tribes, City-States and Nation-States (pp. 325-347). Springer, Cham.

- AN = Anu ša amēli, lines 97-98

- Weeden, Mark (2016), "Haya (god); Spouse of Nidaba/Nissaba, goddess of grain and scribes, he is known both as a "door-keeper" and associated with the scribal arts.", Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses, Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus, UK Higher Education Academy

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Nisaba |

| Look up 𒉀 in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

_-_EnKi_(Sumerian).jpg)