Neurophenomenology

Neurophenomenology refers to a scientific research program aimed to address the hard problem of consciousness in a pragmatic way.[1] It combines neuroscience with phenomenology in order to study experience, mind, and consciousness with an emphasis on the embodied condition of the human mind.[2] The field is very much linked to fields such as neuropsychology, neuroanthropology and behavioral neuroscience (also known as biopsychology) and the study of phenomenology in psychology.

Overview

The label was coined by C. Laughlin, J. McManus and E. d'Aquili in 1990.[3] However, the term was appropriated and given a distinctive understanding by the cognitive neuroscientist Francisco Varela in the mid-1990s,[4] whose work has inspired many philosophers and neuroscientists to continue with this new direction of research.

Phenomenology is a philosophical method of inquiry of everyday experience. The focus in phenomenology is on the examination of different phenomena (from Greek, phainomenon, "that which shows itself") as they appear to consciousness, i.e. in a first-person perspective. Thus, phenomenology is a discipline particularly useful to understand how is it that appearances present themselves to us, and how is it that we attribute meaning to them.[5][6]

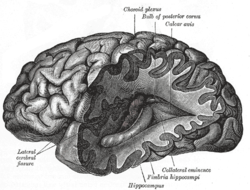

Neuroscience is the scientific study of the brain, and deals with the third-person aspects of consciousness. Some scientists studying consciousness believe that the exclusive utilization of either first- or third-person methods will not provide answers to the difficult questions of consciousness.

Historically, Edmund Husserl is regarded as the philosopher whose work made phenomenology a coherent philosophical discipline with a concrete methodology in the study of consciousness, namely the epoche. Husserl, who was a former student of Franz Brentano, thought that in the study of mind it was extremely important to acknowledge that consciousness is characterized by intentionality, a concept often explained as "aboutness"; consciousness is always consciousness of something. A particular emphasis on the phenomenology of embodiment was developed by philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty in the mid-20th century.

Naturally, phenomenology and neuroscience find a convergence of common interests. However, primarily because of ontological disagreements between phenomenology and philosophy of mind, the dialogue between these two disciplines is still a very controversial subject.[7] Husserl himself was very critical towards any attempt to "naturalizing" philosophy, and his phenomenology was founded upon a criticism of empiricism, "psychologism", and "anthropologism" as contradictory standpoints in philosophy and logic.[8][9] The influential critique of the ontological assumptions of computationalist and representationalist cognitive science, as well as artificial intelligence, made by philosopher Hubert Dreyfus has marked new directions for integration of neurosciences with an embodied ontology. The work of Dreyfus has influenced cognitive scientists and neuroscientists to study phenomenology and embodied cognitive science and/or enactivism. One such case is neuroscientist Walter Freeman, whose neurodynamical analysis has a marked Merleau-Pontyian approach.[10] However, recent trends on the matter appear to reject Dreyfus's interpretation of Husserl while at the same time maintaining a high interest in the integration of Husserlian phenomenology into the sciences of mind, as demonstrated by Evan Thompson's recent work.[11]

See also

- Antonio Damasio

- Autopoiesis

- Biogenetic structuralism

- Embodied cognition

- Francisco Varela

- Hubert Dreyfus

- Walter Freeman

References

- Rudrauf, David; Lutz, Antoine; Cosmelli, Diego; Lachaux, Jean-Philippe; Le Van Quyen, Michel (2003). "From autopoiesis to neurophenomenology: Francisco Varela's exploration of the biophysics of being" (PDF). Biological Research. SciELO Comision Nacional de Investigacion Cientifica Y Tecnologica (CONICYT). 36 (1). doi:10.4067/s0716-97602003000100005. ISSN 0716-9760. PMID 12795206.

- Gallagher, S. 2009. Neurophenomenology. In T. Bayne, A. Cleeremans and P. Wilken (eds.), Oxford Companion to Consciousness (470-472). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Laughlin, Charles (1990). Brain, symbol & experience : toward a neurophenomenology of human consciousness. Boston, Mass: New Science Library. ISBN 978-0-87773-522-9. OCLC 20759009.

- Varela, F. 1996. Neurophenomenology: A methodological remedy for the hard problem. Journal of Consciousness Studies 3: 330-49.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Phenomenology

- Gallagher, S. and Zahavi, D. 2008. The Phenomenological Mind. London: Routledge, Chapter 2.

- Debate Between D. Chalmers and D. Dennett: The Fantasy of First-Person Science

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Edmund Husserl

- Carel, Havi; Meachem, Darian, eds. (2013). Phenomenology and Naturalism: Examining the Relationship between Human Experience and Nature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107699052. Lay summary – Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews (7 October 2014).

- "Hubert Dreyfus 'Intelligence Without Representation: Merleau-Ponty's Critique of Mental Representation'". Archived from the original on 2008-12-01. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- "Evan Thompson. 'Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of Mind. Belknap, Harvard. 2007'"

Further reading

- B. Andrieu. "Brains in the flesh: Prospects for a neurophenomenology". Janus Head 9: 135–155, 2006.

- J. Petitot, F. Varela, B. Pachoud, J-M Roy eds. "Naturalizing phenomenology. Issues in contemporary phenomenology and cognitive science", Stanford University Press, Stanford (California), 1999.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Consciousness studies |

- Eugenio Borrelli page: Phenomenology and Cognitive Science at the Wayback Machine (archived 2012-02-18)

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Phenomenology

- Francisco Varela's Articles on Neurophenomenology and First person Methods

- Michael Winkelman at Archive.today (archived 2012-12-09)

- http://www.neurophenomenology.com

- Hubert Dreyfus 'Intelligence Without Representation: Merleau-Ponty's Critique of Mental Representation'

- Debate Between D. Chalmers and D. Dennett: The Fantasy of First-Person Science