Telephone

A telephone is a telecommunications device that permits two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most efficiently the human voice, into electronic signals that are transmitted via cables and other communication channels to another telephone which reproduces the sound to the receiving user. The term is derived from Greek: τῆλε (tēle, far) and φωνή (phōnē, voice), together meaning distant voice. A common short form of the term is phone, which has been in use since the early 20th century.

In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell was the first to be granted a United States patent for a device that produced clearly intelligible replication of the human voice. This instrument was further developed by many others, and became rapidly indispensable in business, government, and in households.

The essential elements of a telephone are a microphone (transmitter) to speak into and an earphone (receiver) which reproduces the voice in a distant location.[1] In addition, most telephones contain a ringer to announce an incoming telephone call, and a dial or keypad to enter a telephone number when initiating a call to another telephone. The receiver and transmitter are usually built into a handset which is held up to the ear and mouth during conversation. The dial may be located either on the handset or on a base unit to which the handset is connected. The transmitter converts the sound waves to electrical signals which are sent through a telephone network to the receiving telephone, which converts the signals into audible sound in the receiver or sometimes a loudspeaker. Telephones are duplex devices, meaning they permit transmission in both directions simultaneously.

The first telephones were directly connected to each other from one customer's office or residence to another customer's location. Being impractical beyond just a few customers, these systems were quickly replaced by manually operated centrally located switchboards. These exchanges were soon connected together, eventually forming an automated, worldwide public switched telephone network. For greater mobility, various radio systems were developed for transmission between mobile stations on ships and automobiles in the mid-20th century. Hand-held mobile phones were introduced for personal service starting in 1973. In later decades their analog cellular system evolved into digital networks with greater capability and lower cost.

Convergence has given most modern cell phones capabilities far beyond simple voice conversation. Most are smartphones, integrating all mobile communication and many computing needs.

Basic principles

A traditional landline telephone system, also known as plain old telephone service (POTS), commonly carries both control and audio signals on the same twisted pair (C in diagram) of insulated wires, the telephone line. The control and signaling equipment consists of three components, the ringer, the hookswitch, and a dial. The ringer, or beeper, light or other device (A7), alerts the user to incoming calls. The hookswitch signals to the central office that the user has picked up the handset to either answer a call or initiate a call. A dial, if present, is used by the subscriber to transmit a telephone number to the central office when initiating a call. Until the 1960s dials used almost exclusively the rotary technology, which was replaced by dual-tone multi-frequency signaling (DTMF) with pushbutton telephones (A4).

A major expense of wire-line telephone service is the outside wire plant. Telephones transmit both the incoming and outgoing speech signals on a single pair of wires. A twisted pair line rejects electromagnetic interference (EMI) and crosstalk better than a single wire or an untwisted pair. The strong outgoing speech signal from the microphone (transmitter) does not overpower the weaker incoming speaker (receiver) signal with sidetone because a hybrid coil (A3) and other components compensate the imbalance. The junction box (B) arrests lightning (B2) and adjusts the line's resistance (B1) to maximize the signal power for the line length. Telephones have similar adjustments for inside line lengths (A8). The line voltages are negative compared to earth, to reduce galvanic corrosion. Negative voltage attracts positive metal ions toward the wires.

Details of operation

The landline telephone contains a switchhook (A4) and an alerting device, usually a ringer (A7), that remains connected to the phone line whenever the phone is "on hook" (i.e. the switch (A4) is open), and other components which are connected when the phone is "off hook". The off-hook components include a transmitter (microphone, A2), a receiver (speaker, A1), and other circuits for dialing, filtering (A3), and amplification.

The place a telephone call, the calling party picks up the telephone's handset, thereby operating a lever which closes the hook switch (A4). This powers the telephone by connecting the transmission hybrid transformer, as well as the transmitter (microphone) and receiver (speaker) to the line. In this off-hook state, the telephone circuitry has a low resistance of typically than 300 ohms, which causes the flow of direct current (DC) in the line (C) from the telephone exchange. The exchange detects this current, attaches a digit receiver circuit to the line, and sends dial tone to indicate its readiness. On a modern push-button telephone, the caller then presses the number keys to send the telephone number of the destination, the called party. The keys control a tone generator circuit (not shown) that sends DTMF tones to the exchange. A rotary-dial telephone uses pulse dialing, sending electrical pulses, that the exchange counts to decode each digit of the telephone number. If the called party's line is available, the terminating exchange applies an intermittent alternating current (AC) ringing signal of 40 to 90 volts to alert the called party of the incoming call. If the called party's line is in use, however, the exchange returns a busy signal to the calling party. If the called party's line is in use but subscribes to call waiting service, the exchange sends an intermittent audible tone to the called party to indicate another call.

The electromechanical ringer of a telephone (A7) is connected to the line through a capacitor (A6), which blocks direct current and passes the alternating current of the ringing power. The telephone draws no current when it is on hook, while a DC voltage is continually applied to the line. Exchange circuitry (D2) can send an alternating current down the line to activate the ringer and announce an incoming call. In manual service exchange areas, before dial service was installed, telephones had hand-cranked magneto generators to generate a ringing voltage back to the exchange or any other telephone on the same line. When a landline telephone is inactive (on hook), the circuitry at the telephone exchange detects the absence of direct current to indicate that the line is not in use.[2] When a party initiates a call to this line, the exchange sends the ringing signal. When the called party picks up the handset, they actuate a double-circuit switchhook (not shown) which may simultaneously disconnects the alerting device and connects the audio circuitry to the line. This, in turn, draws direct current through the line, confirming that the called phone is now active. The exchange circuitry turns off the ring signal, and both telephones are now active and connected through the exchange. The parties may now converse as long as both phones remain off hook. When a party hangs up, placing the handset back on the cradle or hook, direct current ceases in that line, signaling the exchange to disconnect the call.

Calls to parties beyond the local exchange are carried over trunk lines which establish connections between exchanges. In modern telephone networks, fiber-optic cable and digital technology are often employed in such connections. Satellite technology may be used for communication over very long distances.

In most landline telephones, the transmitter and receiver (microphone and speaker) are located in the handset, although in a speakerphone these components may be located in the base or in a separate enclosure. Powered by the line, the microphone (A2) produces a modulated electric current which varies its frequency and amplitude in response to the sound waves arriving at its diaphragm. The resulting current is transmitted along the telephone line to the local exchange then on to the other phone (via the local exchange or via a larger network), where it passes through the coil of the receiver (A3). The varying current in the coil produces a corresponding movement of the receiver's diaphragm, reproducing the original sound waves present at the transmitter.

Along with the microphone and speaker, additional circuitry is incorporated to prevent the incoming speaker signal and the outgoing microphone signal from interfering with each other. This is accomplished through a hybrid coil (A3). The incoming audio signal passes through a resistor (A8) and the primary winding of the coil (A3) which passes it to the speaker (A1). Since the current path A8 – A3 has a far lower impedance than the microphone (A2), virtually all of the incoming signal passes through it and bypasses the microphone.

At the same time the DC voltage across the line causes a DC current which is split between the resistor-coil (A8-A3) branch and the microphone-coil (A2-A3) branch. The DC current through the resistor-coil branch has no effect on the incoming audio signal. But the DC current passing through the microphone is turned into AC (in response to voice sounds) which then passes through only the upper branch of the coil's (A3) primary winding, which has far fewer turns than the lower primary winding. This causes a small portion of the microphone output to be fed back to the speaker, while the rest of the AC goes out through the phone line.

A lineman's handset is a telephone designed for testing the telephone network, and may be attached directly to aerial lines and other infrastructure components.

History

.jpg)

Before the development of the electric telephone, the term "telephone" was applied to other inventions, and not all early researchers of the electrical device called it "telephone". Perhaps the earliest use of the word for a communications system was the telephon created by Gottfried Huth in 1796. Huth proposed an alternative to the optical telegraph of Claude Chappe in which the operators in the signalling towers would shout to each other by means of what he called "speaking tubes", but would now be called giant megaphones.[4] A communication device for sailing vessels called a "telephone" was invented by the captain John Taylor in 1844. This instrument used four air horns to communicate with vessels in foggy weather.[5][6]

Johann Philipp Reis used the term in reference to his invention, commonly known as the Reis telephone, in c. 1860. His device appears to be the first device based on conversion of sound into electrical impulses. The term telephone was adopted into the vocabulary of many languages. It is derived from the Greek: τῆλε, tēle, "far" and φωνή, phōnē, "voice", together meaning "distant voice".

Credit for the invention of the electric telephone is frequently disputed. As with other influential inventions such as radio, television, the light bulb, and the computer, several inventors pioneered experimental work on voice transmission over a wire and improved on each other's ideas. New controversies over the issue still arise from time to time. Charles Bourseul, Antonio Meucci, Johann Philipp Reis, Alexander Graham Bell, and Elisha Gray, amongst others, have all been credited with the invention of the telephone.[7][2]

Alexander Graham Bell was the first to be awarded a patent for the electric telephone by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) in March 1876.[8] Before Bell's patent, the telephone transmitted sound in a way that was similar to the telegraph. This method used vibrations and circuits to send electrical pulses, but was missing key features. Bell found that this method produced a sound through intermittent currents, but in order for the telephone to work a fluctuating current reproduced sounds the best. The fluctuating currents became the basis for the working telephone, creating Bell's patent.[9] That first patent by Bell was the master patent of the telephone, from which other patents for electric telephone devices and features flowed.[10] The Bell patents were forensically victorious and commercially decisive.

In 1876, shortly after Bell's patent application, Hungarian engineer Tivadar Puskás proposed the telephone switch, which allowed for the formation of telephone exchanges, and eventually networks.[11]

In the United Kingdom the blower is used as a slang term for a telephone. The term came from navy slang for a speaking tube.[12]

Timeline of early development

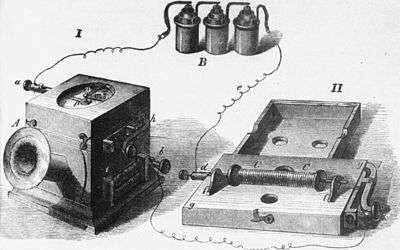

.jpg)

- 1844: Innocenzo Manzetti first mooted the idea of a "speaking telegraph" or telephone. Use of the "speaking telegraph" and "sound telegraph" monikers would eventually be replaced by the newer, distinct name, "telephone".

- 26 August 1854: Charles Bourseul published an article in the magazine L'Illustration (Paris): "Transmission électrique de la parole" (electric transmission of speech), describing a "make-and-break" type telephone transmitter later created by Johann Reis.

- 26 October 1861: Johann Philipp Reis (1834–1874) publicly demonstrated the Reis telephone before the Physical Society of Frankfurt.[2] Reis' telephone was not limited to musical sounds. Reis also used his telephone to transmit the phrase "Das Pferd frisst keinen Gurkensalat" ("The horse does not eat cucumber salad").

- 22 August 1865, La Feuille d'Aoste reported "It is rumored that English technicians to whom Mr. Manzetti illustrated his method for transmitting spoken words on the telegraph wire intend to apply said invention in England on several private telegraph lines". However telephones would not be demonstrated there until 1876, with a set of telephones from Bell.

- 28 December 1871: Antonio Meucci files patent caveat No. 3335 in the U.S. Patent Office titled "Sound Telegraph", describing communication of voice between two people by wire. A 'patent caveat' was not an invention patent award, but only an unverified notice filed by an individual that he or she intends to file a regular patent application in the future.

- 1874: Meucci, after having renewed the caveat for two years does not renew it again, and the caveat lapses.

- 6 April 1875: Bell's U.S. Patent 161,739 "Transmitters and Receivers for Electric Telegraphs" is granted. This uses multiple vibrating steel reeds in make-break circuits.

- 11 February 1876: Elisha Gray invents a liquid transmitter for use with a telephone but does not build one.

- 14 February 1876: Gray files a patent caveat for transmitting the human voice through a telegraphic circuit.

- 14 February 1876: Alexander Graham Bell applies for the patent "Improvements in Telegraphy", for electromagnetic telephones using what is now called amplitude modulation (oscillating current and voltage) but which he referred to as "undulating current".

- 19 February 1876: Gray is notified by the U.S. Patent Office of an interference between his caveat and Bell's patent application. Gray decides to abandon his caveat.

- 7 March 1876: Bell's U.S. patent 174,465 "Improvement in Telegraphy" is granted, covering "the method of, and apparatus for, transmitting vocal or other sounds telegraphically…by causing electrical undulations, similar in form to the vibrations of the air accompanying the said vocal or other sound."

- 10 March 1876: The first successful telephone transmission of clear speech using a liquid transmitter when Bell spoke into his device, "Mr. Watson, come here, I want to see you." and Watson heard each word distinctly.

- 30 January 1877: Bell's U.S. patent 186,787 is granted for an electromagnetic telephone using permanent magnets, iron diaphragms, and a call bell.

- 27 April 1877: Edison files for a patent on a carbon (graphite) transmitter. The patent 474,230 was granted 3 May 1892, after a 15-year delay because of litigation. Edison was granted patent 222,390 for a carbon granules transmitter in 1879.

Early commercial instruments

Early telephones were technically diverse. Some used a water microphone, some had a metal diaphragm that induced current in an electromagnet wound around a permanent magnet, and some were dynamic – their diaphragm vibrated a coil of wire in the field of a permanent magnet or the coil vibrated the diaphragm. The sound-powered dynamic variants survived in small numbers through the 20th century in military and maritime applications, where its ability to create its own electrical power was crucial. Most, however, used the Edison/Berliner carbon transmitter, which was much louder than the other kinds, even though it required an induction coil which was an impedance matching transformer to make it compatible with the impedance of the line. The Edison patents kept the Bell monopoly viable into the 20th century, by which time the network was more important than the instrument.

Early telephones were locally powered, using either a dynamic transmitter or by the powering of a transmitter with a local battery. One of the jobs of outside plant personnel was to visit each telephone periodically to inspect the battery. During the 20th century, telephones powered from the telephone exchange over the same wires that carried the voice signals became common.

Early telephones used a single wire for the subscriber's line, with ground return used to complete the circuit (as used in telegraphs). The earliest dynamic telephones also had only one port opening for sound, with the user alternately listening and speaking (or rather, shouting) into the same hole. Sometimes the instruments were operated in pairs at each end, making conversation more convenient but also more expensive.

At first, the benefits of a telephone exchange were not exploited. Instead telephones were leased in pairs to a subscriber, who had to arrange for a telegraph contractor to construct a line between them, for example between a home and a shop. Users who wanted the ability to speak to several different locations would need to obtain and set up three or four pairs of telephones. Western Union, already using telegraph exchanges, quickly extended the principle to its telephones in New York City and San Francisco, and Bell was not slow in appreciating the potential.

Signalling began in an appropriately primitive manner. The user alerted the other end, or the exchange operator, by whistling into the transmitter. Exchange operation soon resulted in telephones being equipped with a bell in a ringer box, first operated over a second wire, and later over the same wire, but with a condenser (capacitor) in series with the bell coil to allow the AC ringer signal through while still blocking DC (keeping the phone "on hook"). Telephones connected to the earliest Strowger switch automatic exchanges had seven wires, one for the knife switch, one for each telegraph key, one for the bell, one for the push-button and two for speaking. Large wall telephones in the early 20th century usually incorporated the bell, and separate bell boxes for desk phones dwindled away in the middle of the century.

Rural and other telephones that were not on a common battery exchange had a magneto hand-cranked generator to produce a high voltage alternating signal to ring the bells of other telephones on the line and to alert the operator. Some local farming communities that were not connected to the main networks set up barbed wire telephone lines that exploited the existing system of field fences to transmit the signal.

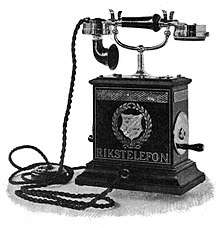

In the 1890s a new smaller style of telephone was introduced, packaged in three parts. The transmitter stood on a stand, known as a "candlestick" for its shape. When not in use, the receiver hung on a hook with a switch in it, known as a "switchhook". Previous telephones required the user to operate a separate switch to connect either the voice or the bell. With the new kind, the user was less likely to leave the phone "off the hook". In phones connected to magneto exchanges, the bell, induction coil, battery and magneto were in a separate bell box or "ringer box".[13] In phones connected to common battery exchanges, the ringer box was installed under a desk, or other out-of-the-way place, since it did not need a battery or magneto.

Cradle designs were also used at this time, having a handle with the receiver and transmitter attached, now called a handset, separate from the cradle base that housed the magneto crank and other parts. They were larger than the "candlestick" and more popular.

Disadvantages of single-wire operation such as crosstalk and hum from nearby AC power wires had already led to the use of twisted pairs and, for long-distance telephones, four-wire circuits. Users at the beginning of the 20th century did not place long-distance calls from their own telephones but made an appointment to use a special soundproofed long-distance telephone booth furnished with the latest technology.

What turned out to be the most popular and longest-lasting physical style of telephone was introduced in the early 20th century, including Bell's 202-type desk set. A carbon granule transmitter and electromagnetic receiver were united in a single molded plastic handle, which when not in use sat in a cradle in the base unit. The circuit diagram of the model 202 shows the direct connection of the transmitter to the line, while the receiver was induction coupled. In local battery configurations, when the local loop was too long to provide sufficient current from the exchange, the transmitter was powered by a local battery and inductively coupled, while the receiver was included in the local loop.[14] The coupling transformer and the ringer were mounted in a separate enclosure, called the subscriber set. The dial switch in the base interrupted the line current by repeatedly but very briefly disconnecting the line 1 to 10 times for each digit, and the hook switch (in the center of the circuit diagram) disconnected the line and the transmitter battery while the handset was on the cradle.

In the 1930s, telephone sets were developed that combined the bell and induction coil with the desk set, obviating a separate ringer box. The rotary dial becoming commonplace in the 1930s in many areas enabled customer-dialed service, but some magneto systems remained even into the 1960s. After World War II, the telephone networks saw rapid expansion and more efficient telephone sets, such as the model 500 telephone in the United States, were developed that permitted larger local networks centered around central offices. A breakthrough new technology was the introduction of Touch-Tone signaling using push-button telephones by American Telephone & Telegraph Company (AT&T) in 1963.

Ericsson DBH 1001 (ca. 1931), the first combined telephone made with a Bakelite housing and handset.

Ericsson DBH 1001 (ca. 1931), the first combined telephone made with a Bakelite housing and handset.- Telephone used by American soldiers (WWII, Minalin, Pampanga, Philippines)

One type of mobile phone, called a cell phone

One type of mobile phone, called a cell phone

Digital telephones and voice over IP

The invention of the transistor in 1947 dramatically changed the technology used in telephone systems and in the long-distance transmission networks, over the next several decades. Along with the development of stored program control for electronic switching systems, and new transmission technologies, such as pulse-code modulation (PCM), telephony gradually evolved towards digital telephony, which improved the capacity, quality, and cost of the network.[15]

The development of digital data communications methods made it possible to digitize voice and transmit it as real-time data across computer networks and the Internet, giving rise to the field of Internet Protocol (IP) telephony, also known as voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP), a term that reflects the methodology memorably. VoIP has proven to be a disruptive technology that is rapidly replacing traditional telephone network infrastructure.

By January 2005, up to 10% of telephone subscribers in Japan and South Korea had switched to this digital telephone service. A January 2005 Newsweek article suggested that Internet telephony may be "the next big thing."[16] The technology has spawned a new industry comprising many VoIP companies that offer services to consumers and businesses.

IP telephony uses high-bandwidth Internet connections and specialized customer premises equipment to transmit telephone calls via the Internet, or any modern private data network. The customer equipment may be an analog telephone adapter (ATA) which translates the signals of a conventional analog telephone to packet-switched IP messages. IP Phones have these function combined in standalone device, and computer softphone applications use microphone and headset devices of a personal computer.

While traditional analog telephones are typically powered from the central office through the telephone line, digital telephones require a local power supply. Internet-based digital service also requires special provisions to provide the service location to the emergency services when a emergency telephone number is called.

Mobile telephony

In 2002, only 10% of the world's population used mobile phones and by 2005 that percentage had risen to 46%.[17] By the end of 2009, there were a total of nearly 6 billion mobile and fixed-line telephone subscribers worldwide. This included 1.26 billion fixed-line subscribers and 4.6 billion mobile subscribers.[18]

Characteristic icons and symbols

The Unicode system provides various code points for graphic symbols used in designating telephone devices, services, or information, for print, signage, and other media.

- U+2121 ℡ TELEPHONE SIGN

- U+260E ☎ BLACK TELEPHONE

- U+260F ☏ WHITE TELEPHONE

- U+2706 ✆ TELEPHONE LOCATION SIGN

- U+2315 ⌕ TELEPHONE RECORDER

- U+01F4DE 📞 TELEPHONE RECEIVER

- U+01F4F1 📱 MOBILE PHONE (HTML

📱) - U+01F4F4 📴 MOBILE PHONE OFF (HTML

📴) - U+01F4F5 📵 NO MOBILE PHONES (HTML

📵) - U+01F57B 🕻 LEFT HAND TELEPHONE RECEIVER

- U+01F57C 🕼 TELEPHONE RECEIVER WITH PAGE

- U+01F57D 🕽 RIGHT HAND TELEPHONE RECEIVER

- U+01F57E 🕾 WHITE TOUCHTONE TELEPHONE (HTML

🕾) - U+01F57F 🕿 BLACK TOUCHTONE TELEPHONE (HTML

🕿) - U+01F581 🖁 CLAMSHELL MOBILE PHONE (HTML

🖁)

See also

References

- "United States Coast Guard Sound-Powered Telephone Talkers Manual, 1979, p. 1" (PDF).

- Kempe, Harry Robert; Garcke, Emile (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 547–57.

- Carroll, Rory (June 17, 2002). "Bell did not invent telephone, US rules" – via www.theguardian.com.

- Holzmann, Gerard J.; Pehrson, Björn, The Early History of Data Networks, pp. 90-91, Wiley, 1995 ISBN 0818667826.

- The Year-book of Facts in Science and Art. Simpkin, Marshall, and Company. July 6, 1845. p. 55 – via Internet Archive.

- "The Telephone and Telephone Exchanges" by J. E. Kingsbury published in 1915.

- Coe, Lewis (1995). The Telephone and It's Several Inventors: A History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7864-2609-6.

- Brown, Travis (1994). Historical first patents: the first United States patent for many everyday things (illustrated ed.). University of Michigan: Scarecrow Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-8108-2898-8.

- Beauchamp, Christopher (2010). "Who Invented the Telephone?: Lawyers, Patents, and the Judgments of History". Technology and Culture. 39: 858–859 – via Project MUSE.

- US 174465 Alexander Graham Bell: "Improvement in Telegraphy" filed on February 14, 1876, granted on March 7, 1876.

- "Puskás, Tivadar". Omikk.bme.hu. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- Rick Jolly (2018). Jackspeak: A guide to British Naval slang & usage. p. 46.

- "Ringer Boxes". Telephonymuseum.com. Archived from the original on 2001-10-12. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- Circuit Diagram, Model 102, Porticus Telephone website.

- Allstot, David J. (2016). "Switched Capacitor Filters". In Maloberti, Franco; Davies, Anthony C. (eds.). A Short History of Circuits and Systems: From Green, Mobile, Pervasive Networking to Big Data Computing (PDF). IEEE Circuits and Systems Society. pp. 105–110. ISBN 9788793609860.

- Sheridan, Barrett. "Newsweek – National News, World News, Health, Technology, Entertainment and more..." MSNBC. Archived from the original on January 18, 2005. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- "Are Cell Phones Ruining Our Social Skills? – SiOWfa15: Science in Our World: Certainty and Controversy". sites.psu.edu.

- Next-Generation Networks Set to Transform Communications, International Telecommunications Union website, 4 September 2007. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

Further reading

- Brooks, John (1976). Telephone: The first hundred years. HarperCollins.

- Bruce, Robert V. (1990). Bell: Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9691-2.

- Casson, Herbert Newton. (1910) The history of the telephone online.

- Coe, Lewis (1995). The Telephone and Its Several Inventors: A History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co.

- Evenson, A. Edward (2000). The Telephone Patent Conspiracy of 1876: The Elisha Gray – Alexander Bell Controversy. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co.

- Fischer, Claude S. (1994) America calling: A social history of the telephone to 1940 (Univ of California Press, 1994)

- Huurdeman, Anton A. (2003). The Worldwide History of Telecommunications Hoboken: NJ: Wiley-IEEE Press.

- John, Richard R. (2010). Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- MacDougall, Robert. The People's Network: The Political Economy of the Telephone in the Gilded Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Mueller, Milton. (1993) "Universal service in telephone history: A reconstruction." Telecommunications Policy 17.5 (1993): 352–69.

- Todd, Kenneth P. (1998), A Capsule History of the Bell System. American Telephone & Telegraph Company (AT&T).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Telephone. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Telephone service for travel. |

| Look up telephone or cordless telephone in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Early U.S. Telephone Industry Data

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Kempe, Harry Robert; Garcke, Emile (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). pp. 547–557.

- Virtual museum of early telephones

- The Telephone, 1877

- The short film "Now You're Talking (1927)" is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film "Communication (1928)" is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film "Telephone Memories (Reel 1 of 2) (1931)" is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film "Telephone Memories (Reel 2 of 2) (1931)" is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- The short film "Far Speaking (ca. 1935)" is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- "US 174,465". pdfpiw.uspto.gov.—Telegraphy (Bell's first telephone patent)—Alexander Graham Bell

- US 186,787—Electric Telegraphy (permanent magnet receiver)—Alexander Graham Bell

- US 474,230—Speaking Telegraph (graphite transmitter)—Thomas Edison

- US 203,016—Speaking Telephone (carbon button transmitter)—Thomas Edison

- US 222,390—Carbon Telephone (carbon granules transmitter)—Thomas Edison

- US 485,311—Telephone (solid back carbon transmitter)—Anthony C. White (Bell engineer) This design was used until 1925 and installed phones were used until the 1940s.

- US 3,449,750—Duplex Radio Communication and Signalling Apparatus—G. H. Sweigert

- US 3,663,762—Cellular Mobile Communication System—Amos Edward Joel (Bell Labs)

- US 3,906,166—Radio Telephone System (DynaTAC cell phone)—Martin Cooper et al. (Motorola)