Navahrudak

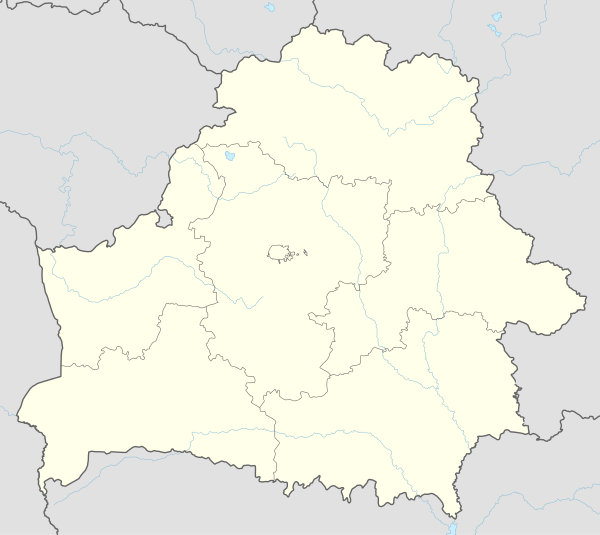

Navahrudak (Belarusian: Навагрудак, Russian: Новогрудок, Novogrudok; Polish: Nowogródek; Lithuanian: Naugardukas) is a city in the Grodno Region of Belarus.

Navahrudak Навагрудак | |

|---|---|

.jpg)

| |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Navahrudak Navahrudak within the Grodno Region | |

| Coordinates: 53°35′N 25°49′E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Grodno |

| District (Rayon) | Navahrudak |

| Founded | 1044 |

| Town rights | 1444 |

| Elevation | 292 m (958 ft) |

| Population (2009)[1] | |

| • Total | 29,336 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 231241, 231243, 231244, 231246, 231400 |

| Area code(s) | +375 1597 |

| License plate | 4 |

| Website | Official website |

In the 14th century, it was an episcopal see of the Metropolitanate of Lithuania. It is a possible first capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, but Kernavė is also noted as a possibility. It was later part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Russian Empire and eventually Poland until the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939 when the Soviet Union annexed the area to the Byelorussian SSR.

History

Early history

Navahrudak was first mentioned in the Sophian First Chronicle and Fourth Novgorod Chronicle in 1044 in reference to a war between Yaroslav I the Wise and Lithuanian tribes.[2] In 1241, it was destroyed by the Mongols.[3] It was also mentioned in the Hypatian Codex in 1252 as Novogorodok, meaning "new little town". Navahrudak was a major settlement in the remote western lands of the Krivichs that came under the control of the Kievan Rus at the end of the 10th century. This hypothesis has been disputed, however, as the earliest archaeological findings date from the 11th century.[4]

In the 13th century, the fragile unity of the Kievan Rus was disintegrated by the nomadic incursions from Asia, which reached a climax with the Mongol horde's Siege of Kiev (1240), resulting in the sacking of Kiev and leaving a geopolitical vacuum in the region, later referred to as Black Ruthenia. The Early East Slavs splintered along pre-existing tribal lines and formed a number of independent, competing principalities.

Mindaugas of Lithuania made use of the plight to annex Navahrudak, which then became part of the Kingdom of Lithuania,[5][6][7][8] later the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. During the 16th century, Maciej Stryjkowski was the first, in his chronicle,[9] to propose the theory that Navahrudak was the capital of the 13th-century state. That statement is supported by several scholars, but others dispute the notion, mainly because contemporary chronicles do not provide any references to Navahrudak being the capital and even state that the city transferred to the Galicia–Volhynia.[10] Vaišvilkas, the son and successor of Mindaugas, took monastic vows in Lavrashev Monastery[11] near Novgorodok and founded an Orthodox convent there.[12] In 1314 the castle was besieged by the Teutonic Knights.[13]

After the Union of Krewo (1385) it was part of the Polish–Lithuanian Union, which became the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth after the Union of Lublin in 1569. It was the capital of the Nowogródek Voivodeship from 1507 until the Third Partition of Poland in 1795.[14]

In 1422, Polish king Władysław II Jagiełło married Sophia of Halshany in the Transfiguration Church in Nowogródek.[15][16][17] Their son Casimir IV Jagiellon granted town rights in 1444.[14] In 1505, the Tatars plundered the city, but they did not capture the castle. In 1511 it was granted Magdeburg rights by King Sigismund I the Old.[16][18] In 1595, King Sigismund III Vasa granted the city a coat of arms depicting Archangel Michael.[17] It was a royal city.[16]

Partitions of Poland

.jpg)

In 1795, as a result of the Third Partition of Poland, it was annexed by Imperial Russia.[15] Administratively, it was part of the Slonim Governorate since 1796, and the Grodno Governorate since 1801. It was transferred to the Minsk Governorate in 1843. The city is one of two possible birthplaces of Polish national poet Adam Mickiewicz. Mickiewicz was baptized in the local Transfiguration Church and spent his childhood in the city.[15]

During the Napoleonic Wars, it was briefly recaptured by the Poles.[15] At that time, mainly Jews, Poles and Lipka Tatars lived in the city.[15] As part of anti-Polish repressions after the January Uprising, the tsarist administration closed down the gymnasium as well as Catholic churches, which were transformed into Orthodox churches.[15] It had a thriving Jewish community. Its 1900 population was 5,015.[19]

During the First World War, the city was under German occupation from 22 September 1915 to 27 December 1918.[3] During the Polish–Soviet War, it changed hands several times. Ultimately captured by the Poles in October 1920, it was confirmed as part of the Second Polish Republic by the Peace of Riga.

Recent history

.jpg)

During the interwar period, Nowogródek served as the seat of the Nowogródek Voivodeship until the 1939 invasion of Poland by Germany and the Soviet Union. Many new buildings were built, including the voivodeship office, district court, tax office, theater, power plant, city bath and a narrow-gauge railway station.[20] In 1938, a museum was created in the former home of Adam Mickiewicz.[15]

On 18 September 1939 Navahrudak was occupied by the Red Army and, on 14 November 1939, incorporated into the Byelorussian SSR. The Polish inhabitants were taken prisoner and exiled, mostly to Siberia and the rest of the Soviet Union. In the administrative division of the new territories, the city was briefly the centre of Navahrudak Voblast until it moved to Baranavichy, and the name of voblast was renamed to Baranavichy Voblast and to the Navahrudak Raion (15 January 1940).

On 22 June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union, and on 4 July, Navahrudak was occupied by the Wehrmacht. Then, the Red Army was surrounded in the Novogrudok Cauldron.

During the German occupation, the city served as the administrative centre of Kreisgebiet Nowogrodek within the Generalbezirk Weißruthenien of Reichskommissariat Ostland. Partisan resistance by Poles immediately began. The Jewish Bielski partisans operated in the region. The local Polish population was subjected to deportations for forced labour to Germany and executions.[15] On 1 August 1943, German troops shot 11 nuns, the Martyrs of Nowogródek. On 8 July 1944, the Red Army recaptured Navahrudak after almost three years of German occupation. During the war, more than 45,000 people were killed in the city and the surrounding area, and over 60% of housing was destroyed.

Navahrudak had been an important Jewish centre. It was home to the Novardok yeshiva, led by Rabbi Yosef Yozel Horwitz, and was the hometown of Rabbi Yechiel Michel Epstein and the Harkavy Jewish family, including Yiddish lexicographer Alexander Harkavy. Before the war, the population was 20,000, approximately half Jewish and half Gentile. Meyer Meyerovitz and Meyer Abovitz were then the rabbis there. During a series of "actions" in 1941, the Germans killed all but 550 of the approximately 10,000 Jews. (The first mass murder of Navahrudak's Jews occurred in December 1941.) Those not killed were sent into slave labour.[3]

After the war, the area remained part of the Byelorussian SSR, and most of the destroyed infrastructure was rapidly rebuilt. On 8 July 1954, following the disestablishment of the Baranavichy Voblast, the raion, along with Navahrudak, became part of the Hrodna Voblast, where it still is, now in Belarus.

Sites

- Navahrudak Castle, sometimes anachronistically called Mindaugas' Castle, was built in the 14th century, was burnt down by the Swedes in 1706, and remains in ruins.

- Construction of the Orthodox SS. Boris and Gleb Church, in Belarusian Gothic style, started in 1519, but was not completed until the 1630s; it was extensively repaired in the 19th century.

- The Roman Catholic Transfiguration Church (1712–23, includes surviving chapels of an older gothic building), where Adam Mickiewicz was baptised.

- Museum of Adam Mickiewicz at the poet's former home; there are also his statue and the "Mound of Immortality", created in his honour by the Polish administration in 1924–1931.

- Museum of Jewish Resistance. Also a red pebble path along the escape route during the heroic escape of ghetto inmates.

- Church of St. Michael, renovated in 1751 and 1831

- Trade rows at the central square

- Pre-war administration buildings, including the Nowogródek Voivodeship Office and the Voivode's House

Some members of the Harkavy family are buried at the old Jewish cemetery of Navahrudak.

Ruins of the castle

Ruins of the castle

House of Adam Mickiewicz

House of Adam Mickiewicz- Church of Saint Michael Archangel

- Trade rows

- Pre-war Voivodeship Office

Climate

The Köppen Climate Classification subtype for this climate is "Dfb" (Warm Summer Continental Climate).[21]

Twin towns - sister cities

Navahrudak is twinned with:[22]

References

- "World Gazetteer". World Gazetteer. Archived from the original on 2013-01-11. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- Н.П.Гайба. История Новогрудка Archived 2010-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Carol Hoffman (2005). Shmuel Spector, Bracha Freundlich (eds.). "Pinkas Hakehillot Polin: Novogrudok". Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities. Jewishgen.org.CS1 maint: uses editors parameter (link)

- "Oshchestvo Srednevekovoj Litvy". Viduramziu.lietuvos.net. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- D. Antanavičius, D. Baronas etc. Mindaugo knyga: istorijos šaltiniai apie Lietuvos karalių. Vilnius, 2005. pp.63-93

- J. Geddie. The Russian Empire: Historical and Descriptive. P.102

- J. Phillips. The Medieval Expansion of Europe. p. 78

- Mindaugas, the King of Lithuania

- Maciej Stryjkowski (1985). Kronika polska, litewska, żmódzka i wszystkiéj Rusi Macieja Stryjkowskiego. Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe. p. 572.

- Полное собрание русских летописей. Ипатьевская летопись. Москва, 1998. pp.880-881

- Following the Tracks of a Myth Archived 2007-06-14 at the Wayback Machine Edvardas Gudavičius

- S.C. Rowell. Lithuania Ascending: A Pagan Empire within East-Central Europe, 1295-1345. Cambridge University Press, 1994. Page 149.

- Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego i innych krajów słowiańskich, Tom VII, Warsaw, 1886, p. 256 (in Polish)

- "Nowogródek". Encyklopedia PWN (in Polish). Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Monika Białkowska. "Historie z Nowogródka". Przewodnik Katolicki (in Polish). Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Melchior Jakubowski, Maksymilian Sas, Filip Walczyna, Miasta wielu religii. Topografia sakralna ziem wschodnich dawnej Rzeczypospolitej, Muzeum Historii Polski, Warsaw 2016, p. 248 (in Polish)

- "Jubileusz 975 rocznicy powstania Nowogródka". Powiat Suwalski (in Polish). Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Wanda Rewieńska, Miasta i miasteczka magdeburskie w woj. wileńskim i nowogródzkim, Lida 1938, p. 11 (in Polish)

- "JewishGen.org". Data.jewishgen.org. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- Melchior Jakubowski, Maksymilian Sas, Filip Walczyna, Miasta wielu religii. Topografia sakralna ziem wschodnich dawnej Rzeczypospolitej, Muzeum Historii Polski, Warsaw 2016, p. 249 (in Polish)

- Climate Summary for Navahrudak

- "Города-побратимы". novogrudok.gov.by (in Russian). Navahrudak. Retrieved 2020-01-13.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Navahrudak. |