Nakhchivan Tepe

Nakhchivan Tepe - an ancient town located within Nakhchivan city, Naxçıvan Autonomous Republic, Azerbaijan.[1] The city is located at the top of a natural hill in the Nakhchivançay valley. The settlement dates at least as far back as 5000 BC.

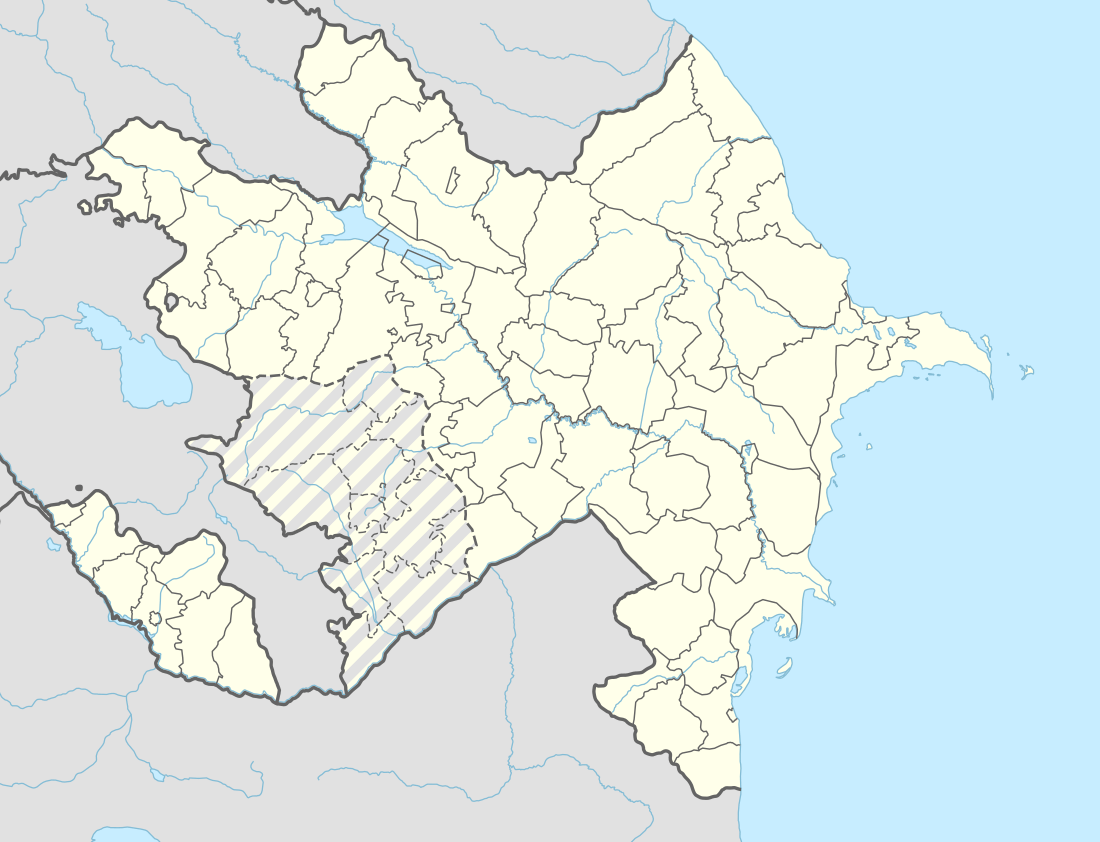

Naxçıvan Təpə (Azerbaijan) | |

Nakhchivan Tepe settlement | |

Shown within Azerbaijan | |

| Location | Nakhchivan, Azerbaijan |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°10′53.7″N 45°25′54.1″E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Periods | Eneolithic Period |

| Cultures | Ancient Turks |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 2017 |

| Archaeologists | Vali Bakshaliyev |

| Ownership | Agriculture and livestock |

Research

Archaeological research in Nakhchivan Tepe under the direction of Veli Bakhshaliyev of the Nakhchivan branch of the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences began in 2017.

The existence of connections between the cultures of the South Caucasus and the Middle East (including Mesopotamia) has drawn the attention of researchers for many years. Researchers such as R.M. Munchayev,[2] O.A. Abibullayev,[3] I.G. Narimanov,[4] T.I. Akhundov[5] and others spoke about the spread and distribution of cultures from the Middle East in the South Caucasus. Although separate finds validated the existence of these connections, they have been confirmed by a complex of archeological materials, including from Nakhchivan Tepe, which is characterized by Dalma Tepe ceramics, a cultural assemblage that was first found in the South Caucasus at the site.

The first settlers of Nakhchivan Tepe used rooms that were partly dug into the ground, and partly constructed from mud bricks. Rooms of this kind have also been uncovered in excavation of the Ovçular Tepesi and Yeni Yol settlements. Charcoal remains are rare, despite abundant accumulations of ash. This demonstrates that wood was very rarely used as a fuel. The majority of archaeological materials from the site are pottery and chips of obsidian, but there are also a few tools. Rarer items include a grinding stone, a flint product and a bone tool. The majority of tools are obsidian, including a few blades for sickles, which give some information on the character of the economy.

Animal bones show that the residents generally engaged in small cattle breeding.[6] Hunting took an insignificant place in the economy. Bones of horses and dogs are represented by single examples. No botanical remains have been found. In the settlement layers, charcoal remains are insignificant, and washing the ashy remains from various hearths has not yielded results. Archeologists hope that this type of research in the future will reveal information on the economy of Nakhchivan Tepe.

Pottery

The pottery is generally characteristic of the first half of the 5th millennium BC. Coal from the lower horizon has been dated to 4945 BC.[7] It is generally characterized by Dalma Tepe painted and impressed ceramics. Excluding single finds, no other entire complex of such ceramics had not been revealed in the South Caucasus. Therefore, the pottery of the settlement of Nakhchivan Tepe has important value for studying the Chalcolithic Age culture of the region.

The ceramics can be divided into two periods based on the stratigraphy of the settlement. However, the two groups coincide to a certain degree in terms of the technology of production and ornamentation. The ceramics were produced mainly by the coil method, with the application of two layers of potter clay to each other. A thin layer of clay covered the surfaces of some vessels. This was done in some cases to change the color, and, in others, for ornamental purposes. Some products were ornamented with finger impressions, which are sometimes executed inaccurately and mixed together. The finger impressions remained after being stuck in the thin upper clay layer. This coating method also was used in the restoration and repair of ceramics. The pottery is generally made with chaff inclusions, and fired to different shades of red. Pottery with sand inclusion is represented by a single copy. Gray wares are also represented by a single piece.

The pottery from the top horizon belongs to the first period. As has already been described, this horizon is characterized by rectangular architecture. The ceramic products of this horizon can be divided into six groups: plain pottery, painted ceramics, pottery painted in red without an ornament, ceramics with impressed ornaments including fingertip impressions, pottery decorated with a stamp from the edge of a tool, and pottery decorated with an edge ornament in the form of horizontal strips.

In 2010–2016, new Chalcolithic Age monuments were reported from the Nakhchivançay and Sirabçay valleys.[8] Together with Nakhchivan Tepe, these can be used to specify a period of Chalcolithic Age monuments of the South Caucasus. The ceramic complex of Nakhchivan Tepe is very similar to that of Dalma Tepe. The type of painted ceramics of the Dalma Tepe are known from the settlements of Uzun Oba and Uçan Ağıl. Impressed ceramics have been attested at Uçan Ağıl by a single copy, but have not been found in other settlements. Similar ceramics have also been found in isolated copies in monuments in Karabakh. Monuments in the Lake Urmia basin generally use Syunik obsidian.[9] The settlements of Nakhchivan generally used Gekche obsidian from the lake basin in present-day Sevan. Even though Syunik is closer to Nakhchivan than to Gekce, in Nakhchivan, Syunik obsidian is not common. Apparently, the tribe occupying the Lake Urmia basin had connections to the obsidian deposits of the Zangezur Mountains by means of the tribes of Nakhchivan. The recent recovery of a stone hammer in the Nakhchivançay valley with remains of copper on it demonstrates that the connections between these tribes and the Zangezur Mountains were not only for deposits of obsidian, but also for copper deposits.

Dalma Tepe ceramics were explored for the first time at the settlement of the same name by Charles Burney's excavation in 1959, and then also in 1961 to Cuyler Young.[10] Similar ceramics were uncovered from the settlements of Hasanlu, Haji-Firuz,[11] and Tepe Seavan.[12] Dalma Tepe ceramics have been found in Iran and Iraq together with typical Halaf and Obeid ceramics. Similar ceramics have been discovered at Zagros Mountains monuments, such as at settlements of the Kangavar Valley like Seh Gabi B. and Godin Tepe. Numerous Dalma Tepe ceramics also were found in the Mahidasht Valley among the surface materials of 16 settlements. Among these monuments is the Tepa Siahbid settlement, Choga Maran, and Tepe Kuh.[13] Dalma Tepe ceramics were prevalent among the superficial material at Tepe Kuh. Similar ceramics also were found in Iraq at the settlement of Jebel, Kirkuk, Tell Abad, Kheit Qasim, and Yorgan Tepe. Such ceramics also prevailed in the Kangavar valley, but in the Mahidasht valley, the percent of Dalma Tepe ceramics decreased very sharply. Whereas in the Kangavar valley these ceramics comprised 68%, in Mahidasht the number was 24%.[13] This shows that this type of ceramics lessened to the south. Although it was assumed earlier that similar ceramics were widespread to the south and west of the Lake Urmia basin, it is now known that similar ceramics were also present to the north of Lake Urmia and in Nakhchivan. In the territory of Iranian Azerbaijan, this culture also is revealed from settlements at Culfa Kültepe, Ahranjan Tepe, Lavin Tepe, Ghosha Tepe, Idir Tepe and Baruj Tepe. Now, similar ceramics have been discovered in Southern Azerbaijan at more than 100 monuments. Some of these settlements belonged to settled populations, while others belonged to nomadic tribes.[14] According to researchers, this culture blossomed in northwestern Iran and extended from there to the south and the west of the Lake Urmia basin. Chemical analysis of Dalma Tepe ceramics has shown that they were made locally.

References

- Vəli Baxşəliyev, Zeynəb Quliyeva, Turan Həşimova, Kamran Mehbaliyev, Elmar Baxşəliyev. Naxçivan təpə yaşayiş yerində arxeoloji tədqiqatlar. Naxçıvan, Əcəmi, 2018, 266 s.

- Мунчаев Р.М., Амиров Ш.Н. Взаимосвязи Кавказа и Месопотамии в VI-IV тыс. до н.э. Международная научная конференция, 11-12 сентября 2008, Баку: Чашыоглы, 2009, с.41-52.

- Абибуллаев О.А. Энеолит и бронза на территории Нахичеванской АССР. Баку: Элм, 1982, c. 72.

- Нариманов И.Г. Обеидские племена Месопотамии в Азербайджане. Тезисы Всесоюзной археологической конференции. Баку, 1985, c. 271-277.

- Achundov T. Sites des migrants venus du Proche-Orient en Transcaucasie, in Les cultures du Caucase (VIe - IIIe millénaires avant notre ère). Leurs relations avec le Proche Orient, B. Lyonnet ed., Éditions Re-cherche sur les Civilisations, CNRS Éditions: Paris, 2007, p. 95-122.

- The Faunal remains are investigated by Remy Berthon.

- This work was supported by the Science Development Foundation under the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan - Grant № EİF-KETPL-2-2015-1(25)-56/47/5.

- Бахшалиев В.Б новые энеолитические памятники на территории нахчывана// Российская археология, 2014, № 2, c. 88-95; Бахшалиев В.Б. Новые материалы эпохи неолита и энеолита на территории Нахчывана // Российская археология, 2015, № 2, с. 136-145

- Khademi N., F., Abedi A., Glascock M. D., Eskandari N. and Khazaee M. Provenance of prehistoric obsidian artifacts from Kul Tepe, Northwestern Iran using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis // Journal of Archaeological Science, 2013, 40. p. 1956-1965.

- Hamlin C. Dalma Tepe, Iran, 13, 1975, pp. 111–127.

- Voigt M.M. Hajji Firuz Tepe, Iran: The Neolithic Settlement. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1983, p. 20.

- Solecki R. L. and Solecki R. S. Tepe Sevan: A Dalma period site in the Margavar valley, Azerbaijan, Iran, Bulletin of the Asia Institute of Pahlavi University, 3, 1973, pp. 98–117.

- Henrickson. E. F. and Vitali. V. The Dalma Tradition: Prehistoric Inter-Regional Cultural Integration Highland Western Iran, Paleorient, Vol. 13, № 2, 1987, pp. 37-45.

- Abedi A. Iranian Azerbaijan Pathway From The Zagros To The Caucasus, Anatolia And Northern Mesopotamia: Dava Göz, A New Neolithic And Chalcolithic Site In NW Iran. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol. 17, № 1 (2017) pp. 69-87.