Muslim Rajputs

Muslim Rajputs are the patrilineal descendants of Rajputs of Northern regions of the Indian subcontinent who are followers of Islam.[1] Today, Muslim Rajputs can be found in present-day Northern India and eastern parts of Pakistan.[2] They are further divided into different clans.

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| |

| Languages | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Rajputs |

History

The term Rajput is traditionally applied to the original Suryavanshi, Chandravanshi and Agnivanshi clans, who claimed to be Kshatriya in the Hindu varna system.

Conversion to Islam and ethos

There are recorded instances of recent conversions of Rajputs to Islam in Western Uttar Pradesh, Khurja tahsil of Bulandshahr.[3]

Despite the difference in faith, where the question has arisen of common Rajput honour, there have been instances where both Muslim and Hindu Rajputs have united together against threats from external ethnic groups.[4]

Medieval Muslim Rajput dynasties of the Indian subcontinent

Kharagpur Raj

The Kharagpur Raj was a Muslim Kindwar Rajput chieftaincy in modern-day Munger district of Bihar.[5][6] Raja Sangram Singh led a rebellion against the Mughal authorities and was subsequently defeated and executed. His son, Toral Mal, was made to convert to Islam and renamed as Roz Afzun. Roz Afzun was a loyal Commander to the Emperors Jahangir and Shah Jahan and Jahangir referred to him as his "favourite" commander in the empire.[7] Another prominent chieftain of this dynasty was Tahawar Singh who played an active role in the Mughal expedition against the nearby Cheros of Palamu.[8]

Gujarat Sultanate

The Gujarat Sultanate was an independent Muslim Rajput kingdom established in the early 15th century by the Muzaffarid dynasty in Gujarat. The Muzaffarids were descended from Hindu Tanka Rajputs with origins in Thanesar in modern-day Haryana.[9] Under the dynasty, trade, culture, and Indo-Islamic architecture flourished. The city of Ahmedabad was founded by the dynasty.

Khanzada Dynasty

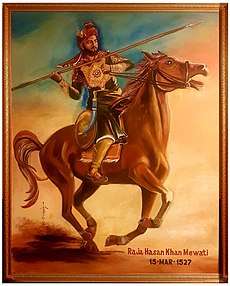

Mewat was a kingdom in Rajputana with its capital at Alwar ruled by a Khanzada Rajput dynasty during the period of the Delhi Sultanate in India. Mewat was covered over a wide area, it included Hathin tehsil, Nuh district, Tijara, Gurgaon, Kishangarh Bas, Ramgarh, Laxmangarh Tehsils Aravalli Range in Alwar district and Pahari, Nagar, Kaman tehsils in Bharatpur district of Rajasthan and also some part of Mathura district of Uttar Pradesh. The last ruler of Mewat, Hasan Khan Mewati was killed in the battle of Khanwa against the Mughal emperor Babur. The Khanzadas were descended from Hindu Jadaun Rajputs.[10]

Qaimkhanis of Fatehpur-Jhunjhunu

The Qaimkhanis were a Muslim Rajput dynasty who were notable for ruling the Fatehpur-Jhunjhunu region in Rajasthan from the 1300s to the 1700s.[11][12] They were descended from Hindu Chauhan Rajputs.

Lalkhani Nawabs

The Lalkhanis are a Muslim Rajput community and a sub-clan of the Bargujars. They were the Nawabs of various estates in Western Uttar Pradesh. These included Chhatari and neighbouring regions including parts of Aligarh and Bulandshahr.[13]

Mayi chiefs

The Mayi clan were the chieftains of the Narhat-Samai (Hisua) chieftaincy in modern-day Nawada district in South Bihar. The founder of the Mayi clan was Nuraon Khan who arrived in Bihar in the 17th century. His descendants were Azmeri and Deyanut who were granted zamindari rights over six parganas by the Mughal authorities. Deyanut's son was Kamgar Khan who expanded his land by attacking and plundering neighbouring zamindars. Kamgar Khan also led numerous revolts against the Mughals and attempted to assert the Mayi's independence. His descendant was Iqbal Ali Khan who took part in the 1781 revolt in Bihar against the British however his revolt failed and Mayi's lost much of their land.[14]

Notable people in medieval India

- Raja Hasan Khan Mewati, was the ruler of Mewat

- Isa Khan, was the Chief of the Baro Bhuiyans (twelve landlords) of 16th century Bengal. His grandfather was a Bais Rajput from Ayodhya in modern-day Uttar Pradesh who migrated to Bengal. Throughout his reign he resisted the Mughal Empire.

Beliefs and customs

Muslim Rajputs often retain common social practices (such as purdah [seclusion of women], which is generally followed by Hindu and Muslim Rajputs).[2]

See also

- List of Rajput dynasties

- Sindhi-Sipahi

References

- "UNHCR Refugee Review Tribunal. IND32856, 6 February 2008" (PDF).

- "Rajput". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- Muslim Women by Zakia A. Siddiqi, Anwar Jahan Zuberi, Aligarh Muslim University, India University Grants, M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd., 1993, p93

- Self and sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850 by Ayesha Jalal, Routledge 2000, p480, p481

- Tahir Hussain Ansari (20 June 2019). Mughal Administration and the Zamindars of Bihar. Taylor & Francis. pp. 22–28. ISBN 978-1-00-065152-2.

- Yogendra P. Roy (1999). "Agrarian Reforms in "Sarkar" Munger under Raja Bahrox Singh (1631-76) Of Kharagpur". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 60: 287–292. JSTOR 44144095.

- Yogendra P. Roy (1993). "Raja Roz Afzun of Kharagpur (AD 1601 - 31". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 54: 357–358. JSTOR 44142975.

- Yogendra P. Roy (1992). "Tahawar Singh-A Muslim Raja of Kharagpur Raj (1676 - 1727)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 53: 333–334. JSTOR 44142804.

- Aparna Kapadia (16 May 2018). Gujarat: The Long Fifteenth Century and the Making of a Region. Cambridge University Press. pp. 183–185. ISBN 978-1-107-15331-8.

- Bharadwaj, Suraj (2016). State Formation in Mewat Relationship of the Khanzadas with the Delhi Sultanate, the Mughal State, and Other Regional Potentates. Oxford University Press. p. 11. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- Sunita Budhwar (1978). "The Qayamkhani Shaikhzada Family of Fatehpur-Jhunjhunu". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 39: 412–425. JSTOR 44139379.

- Dr Dasharatha Sharma, Kyam Khan Raso, Ed. Dasharath Sharma, Agarchand Nahta, Rajsthan Puratatva Mandir, 1953, page-15

- Eric Stokes (1978). The Peasant and the Raj: Studies in Agrarian Society and Peasant Rebellion in Colonial India. CUP Archive. pp. 199–. ISBN 978-0-521-29770-7.

- Gyan Prakash (30 October 2003). Bonded Histories: Genealogies of Labor Servitude in Colonial India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 87–89. ISBN 978-0-521-52658-6.